Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.105 n.3 Pretoria Mar. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.9407

FORUM

CLINICAL ALERT

Recommendations for the treatment and prevention of malaria: Update for the 2015 season in South Africa

L H Blumberg

Infectious diseases specialist and microbiologist, and Head of the Division of Public Health Surveillance and Response at the National Institute for Communicable Disease, Johannesburg, South Africa. She has compiled this article for the South African Malaria Elimination Committee (SAMEC), the national malaria advisory group to the National Department of Health, Pretoria, South Africa, in her capacity as chairperson

ABSTRACT

Notified malaria cases in South Africa (SA) decreased significantly over the past 14 years, from over 60 000 in the 1999/2000 malaria season to less than 13 000 in 2013/2014. However, the past two seasons have seen increases in both local and imported cases. Mozambique contributes the highest number of imported cases in SA. This update provides recommendations for malaria treatment and prevention (in travellers and residents) for 2015.

Management of malaria

Key components of successful management are early and accurate diagnosis (Table 1) and prompt treatment with effective drugs.

Treatment should ideally be based on confirmed parasitological diagnosis.[1,2] Microscopy of Giemsa-stained thick and thin blood smears remains the diagnostic mainstay.[3] Rapid antigen detection diagnostic tests (RDTs) are more widely accessible than expert microscopy, provide prompt results and are adequately sensitive for Plasmodium falciparum infections. However, RDTs cannot quantify parasite density (so do not detect hyperparasitaemia that indicates severe malaria) and are less sensitive for non-falciparum species than for falciparum infections. RDTs are unsuitable for monitoring treatment response because of antigen persistence.[4] A negative (rapid or microscopy) test does not exclude malaria; repeat testing within 8 - 24 hours, without attempting to coincide with fever peak timing, is mandatory until a positive result or an alternative definitive diagnosis is achieved. Blood smears should be checked for malaria whenever thrombocytopenia is unexpectedly identified. Test any patient with unexplained fever for malaria, even in the absence of a travel history. Occasionally, infected mosquitoes are transported from endemic areas in suitcases and vehicles (Odyssean malaria).[5] All malaria cases must be notified to local health authorities.

Treatment of malaria

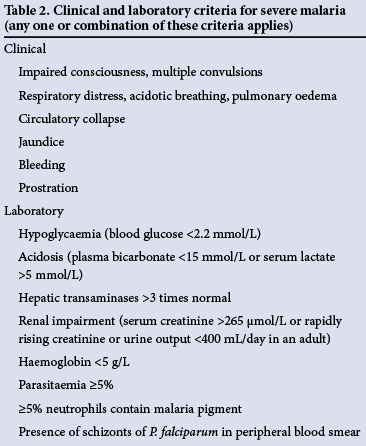

The choice and route of treatment depends primarily on disease severity, which is often underestimated. Uncomplicated malaria is symptomatic infection without signs of severity or evidence of vital organ dysfunction. Persistent vomiting, clinical jaundice, change in mental state or increase in respiratory rate constitutes severe malaria (Table 2).[6,7]

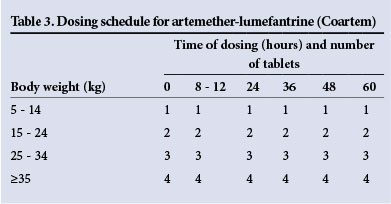

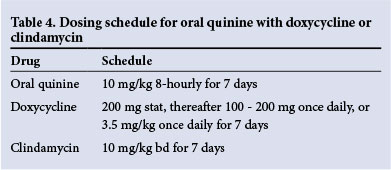

Treat uncomplicated malaria with artemether-lumefantrine (Coartem) (Table 3).[2] For optimal absorption it must be taken with milk or fat-containing food. Adequate fluids, temperature control with paracetamol, and careful follow-up are important. Avoid non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Patients should respond clinically and parasitologically within 24 - 48 hours. Consider poor compliance, misdiagnosis and possible drug resistance if no significant improvement occurs within 72 hours. Artemether-lumefantrine remains efficacious in South Africa (SA),[8,9] with no reports of artemisinin resistance in Africa as yet. In the rare event of artemether-lumefantrine treatment failure despite full compliance, give a full directly observed 7-day course of oral quinine (plus doxycycline or clindamycin) in hospital.

Oral quinine, combined with 7 days of doxycycline, remains an alternative to artemether-lumefantrine (Table 4), but compliance is poor. In pregnancy or children aged <8 years, substitute clindamycin for doxycycline (Table 4). Doxycycline or clindamycin add no early treatment benefit, so are started only once symptoms improve, as gastrointestinal side-effects may exacerbate those of quinine.

Drug interactions

Concomitant use of certain other drugs (e.g. efavirenz, rifampicin) may alter blood concentrations of artemether-lumefantrine and quinine. There is no evidence of the clinical significance of these interactions, but full adherence and fat co-administration is advised, and response to treatment should be monitored particularly carefully.

Pregnancy

First trimester. Supervised 7-day course of oral quinine plus clindamycin.

Second and third trimesters. Artemether-lumefantrine is considered safe and efficacious.

Large adults

Artemether-lumefantrine is registered in SA only for use in patients weighing <65 kg. Minimal pharmacokinetic data exist for larger patients; one study suggests a trend towards increased risk of treatment failure in patients >80 kg.[10] Again, adequate adherence and fat co-administration is important, with careful monitoring of response. If adherence is assured, consider administering the same total dose over 5 days (dosing at 0, 8, 24, 48, 72 and 96 hours).

Recommendations for non-falciparum malaria

Malaria species should be confirmed by a reliable laboratory. Non-falciparum infections are usually uncomplicated, but occasionally produce severe illness. Use artemether-lumefantrine for initial therapy of uncomplicated P. vivax and P. ovale infections. To prevent relapses, this should be followed by a course of primaquine after excluding glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency.

The recommended dose in children is 0.25 - 0.3 mg/kg daily for 14 days, and that for adults is 15 mg daily for 14 days. Currently primaquine is only available on a named-patient basis with Section 21 MCC approval.

Severe malaria (Table 5)

Severe malaria is a medical emergency requiring prompt parenteral treatment, intensive nursing care, and careful monitoring and management of complications.^7 Intravenous artesunate (2.4 mg/kg at 0, 12 and 24 hours, then daily until the patient is able to tolerate oral treatment) is preferred treatment, but is currently unregistered and only available on a named-patient basis with Section 21 MCC approval.[2,11] When intravenous artesunate is not promptly available, intravenous quinine (with an initial loading dose of 20 mg/kg and then maintenance doses of 10 mg/kg, each dose slowly infused over at least 4 hours) is initiated urgently and given 8-hourly until oral treatment is tolerated. Follow with a complete course of artemether-lumefantrine.[2] Reassess frequently to ensure that all complications are promptly detected and optimally managed.

Critical issues in management of severe malaria

Hypoglycaemia. Urgently exclude (or administer empiric glucose) if there is a depressed level of consciousness or convulsions. Repeat glucose monitoring 4-hourly.

Renal failure. This is a frequent, early complication in adults. Severe malaria requires careful fluid management, with frequent measurement of renal function (urea, electrolytes and creatinine), ongoing monitoring of urine output and judicious fluid administration. Strictly avoid overhydration, as the acute respiratory distress syndrome is a common and difficult-to-treat complication, particularly in pregnancy.

Prevention of malaria

Prevention of mosquito bites is the mainstay of malaria prevention. Malaria-transmitting mosquitoes generally bite at night, so people in malaria-endemic areas should ideally remain indoors from dusk to dawn, and sleep under insecticide-treated bednets in rooms with screened windows and doors. Fig. 1 shows endemic areas in SA; residents and travellers in these areas should take necessary precautions to avoid mosquito bites.

Effective repellents contain DEET (diethyl toluamide). Use products containing 20 - 50% DEET for long-lasting protection for adults and children aged >2 months. Products containing >50% DEET have no additional benefit. Avoid applying to eyes or mouth. Additionally, travellers to malaria-endemic areas should use chemoprophylaxis depending on the malaria risk assessment. Three similarly effective chemoprophylactic agents are currently registered in SA (Table 5), all requiring a doctor’s prescription. Selection should be based on patient factors (Table 6) and which option is likely to be best tolerated for optimal adherence.

Scope of protection

Chemoprophylactics are most effective against parasite asexual blood stages. While they will prevent initial illness caused by all species, they will not prevent relapses due to P. vivax and P. ovale.

References

1. World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria. 2nd ed. Geneva: WHO, 2010. http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/9789241547925/en/ (accessed 14 January 2015). [ Links ]

2. South African National Department of Health. Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria in South Africa. Pretoria: NDoH, 2010. [ Links ]

3. Payne D. Use and limitations of light microscopy for diagnosing malaria at primary health care level. Bull World Health Organ 1988;66(5):621-626. [ Links ]

4. Bell DR, Wilson DW, Martin LB. False-positive results of a Plasmodium falciparum histidine-rich protein 2-detecting malaria rapid diagnostic test due to high sensitivity in a community with fluctuating low parasite density. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2005;73(1):199-203. [ Links ]

5. Frean J, Brooke B, Thomas J, Blumberg L. Odyssean malaria outbreaks in Gauteng Province, 2007-2013. S Afr Med J 2014;104(5):335-338. [http://di.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.7684] [ Links ]

6. World Health Organization. Management of Severe Malaria - a Practical Handbook. 3rd ed. Geneva: WHO, 2013. http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/9789241548526/en/ (accessed 14 January 2015). [ Links ]

7. World Health Organization. Severe malaria. Trop Med Int Health 2014;19(Suppl 1):1-131. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/tmi.12313_2] [ Links ]

8. Barnes KI, Durrheim DN, Little F, et al. Effect of artemether-lumefantrine policy and improved vector control on malaria burden in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. PloS Med 2005;2:e330. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1371%2Fjournal.pmed.0020330] [ Links ]

9. Vaughan-Williams CH, Raman J, Raswiswi E, et al. Assessment of the therapeutic efficacy of artemether-lumefantrine in the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in northern KwaZulu-Natal: an observational cohort study. Malar J 2012;11:434. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-11-434] [ Links ]

10. Leykin Y, Miotto L, Pellis T. Pharmacokinetic considerations in the obese. Best Pract Res Clinical Anesthesiol 2011;25(1):27-36. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bpa.2010.12.002] [ Links ]

11. Kift EV, Kredo T, Barnes KI. Parenteral artesunate access programme aims at reducing malaria fatality rates in South Africa. S Afr Med J 2011;101(4):240-241. [ Links ]

12. Schlegenhauf P, Blumentals WA, Suter P, et al. Pregnancy and fetal outcomes after exposure to mefloquine in the pre- and periconception period and during pregnancy. Clin Infect Dis 2012;54(11):e124-131. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/cid/cis215] [ Links ]

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Update: New recommendations for mefloquine use in pregnancy. http://www.cdc.gov/malaria.new_info/2011.mefloquine_pregnancy.html (accessed 14 January 2015). [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Lucille Blumberg

lucilleb@nicd.ac.za

Accepted 26 January 2015.

This month in the SAMJ ...

Maud Lemoine* is a clinical senior lecturer and honorary consultant in hepatology at St Mary's Hospital, Imperial College London. She completed her medical degree and a PhD in physiology and physiopathology in Paris, France, where she also graduated in political sciences from the Institute of Political Studies. She worked at the Medical Research Council laboratories in The Gambia, West Africa, running the PROLIFICA (Prevention of Liver Fibrosis and Cancer in Africa) project (EU-FP7) on hepatitis B virus and liver cancer. She is also leading a study on HIV/hepatitis C virus co-infection in Vietnam, funded by the ANRS (the French research agency on HIV/AIDS and viral hepatitis), and is co-investigator in a forthcoming pilot study on sofobuvir/ribavirin-based, interferon-free therapy in Cameroon, Cote d'Ivoire and Senegal. She is a member of the World Health Organization scientific advisory board for the development of hepatitis C guidelines and of the ANRS.

*Howell J, Ladep NG, Lemoine M, et al. Prevention of Liver Fibrosis and Cancer in Africa: The PROLIFICA project - a collaborative study of hepatitis B-related liver disease in West Africa. S Afr Med J 2015;105(3):185-186. [http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.8880]