Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.105 n.2 Pretoria Feb. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.8638

CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION

CASE REPORT

Digoxin therapy in the modern management of cardiovascular disease: An unusual but serious complication

P MkokoI; N MokheleI; M NtsekheII; N A B NtusiIII

IMB ChB; Cardiac Clinic, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Groote Schuur Hospital and University of Cape Town, South Africa

IIMD, PhD; Cardiac Clinic, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Groote Schuur Hospital and University of Cape Town, South Africa

IIIFCP (SA), DPhil; Cardiac Clinic, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Groote Schuur Hospital and University of Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

A 67-year-old woman presented to the Emergency Unit, Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa, with a 1-week history of poor appetite, vomiting and fatigue. Her background history was notable for infundibular pulmonary stenosis resection, pulmonary embolism and atrial flutter. Two days before, she complained to her general practitioner of recent-onset, recurrent syncope and worsening gastrointestinal upset. Her medical treatment included warfarin 5 mg daily, enalapril 5 mg twice daily, furosemide 40 mg twice daily, atenolol 50 mg twice daily, amiodarone 200 mg daily and digoxin 0.125 mg daily. The digoxin was added to her therapy 8 months earlier to optimise rate control.

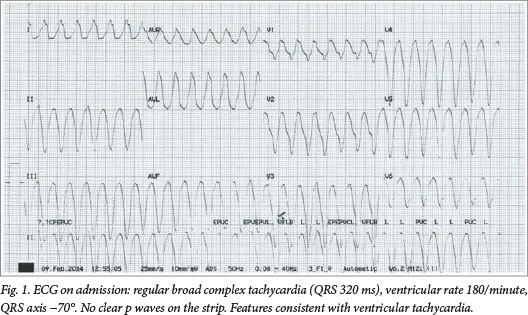

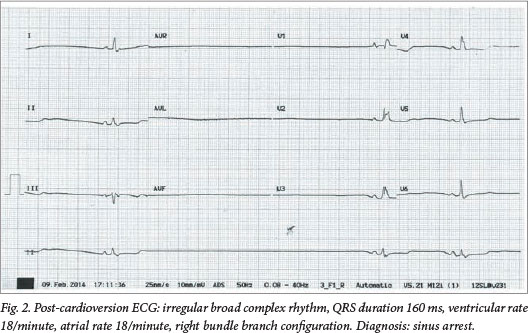

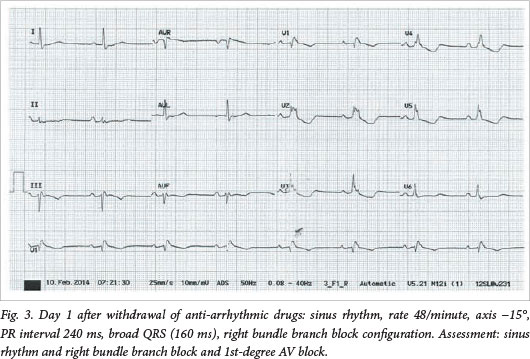

On examination, the patient was cold and clammy, with an unrecordable blood pressure. The ECG showed monomorphic ventricular tachycardia, at a rate of 180/minute (Fig. 1). Direct current cardioversion was performed and a repeat ECG (Fig. 2) revealed sinus arrest with partial right bundle branch block. She underwent temporary transvenous pacing and was admitted to the cardiac intensive care unit. Admission blood tests confirmed digoxin toxicity: serum digoxin concentration 3.2 ng/mL (normal range: 0 - 2). Administration of the digoxin, atenolol and amiodarone was immediately discontinued; the arrhythmia gradually improved over the next day (Fig. 3). A final diagnosis of digoxin toxicity complicated by ventricular tachycardia, sinus arrest and 1st-degree atrioventricular (AV) block was made. The patient was discharged from hospital feeling much better, and digoxin therapy was discontinued.

Discussion

First described in 1785 by William Withering, cardiac glycosides have been used in the treatment of heart failure for >200 years,[1] and digoxin had been the most commonly used of these compounds. Owing to adverse effects and the availability of improved drugs for heart failure, its popularity as the drug of choice has declined. Digoxin has a positive inotropic effect, shifts the Frank-Starling curve upward and leftward, and results in greater stroke volume generation for a given myocardial contraction,[2] achieved through altered balance in the handling of intracellular Na+ and Ca2+ from its potent inhibition of the Na+/K+ ATPase. Increased intracellular Ca2+ potentiates the action of myocardial contractile proteins.!21 At physiological levels, digoxin slows the sinus rate, prolongs the AV node refractory period and has parasympathomimetic effects.[3] At toxic concentrations, digoxin leads to arrhythmias secondary to increased cell excitability from decreased resting cellular membrane potentials and after depolarisations.

Up to 80% of ingested digoxin is absorbed, with a half-life of 36 - 48 hours (which is significantly increased in patients with renal disease).[4] Owing to extensive fat distribution, dialysis is ineffective in removing digoxin.[1] Furthermore, digoxin has multiple metabolic effects (including hypokalaemia, hypomagnesaemia and hypo-calcaemia) and drug interactions, which accentuate its toxicity. Concomitant use of diuretics increases the incidence of digoxin toxicity by decreasing the glomerular filtration rate and inducing electrolyte imbalances. Administration with other anti-arrhythmic agents may provoke pro-arrhythmic events.[3]

Clinical manifestations of digoxin toxicity are cardiac and extracardiac. Cardiac manifestations can be classified as follows:

- Ectopic rhythms due to re-entry or enhanced automaticity: atrial tachycardia with a block, junctional tachycardia, ventricular premature complexes, ventricular tachycardia.

- Depression of pacemakers: manifested as sinus arrest.

- Depression of conduction: manifested as AV block or sinoatrial node exit block. First-degree AV block and Mobitz type Ι 2nd-degree AV block are common manifestations. Mobitz type ΙΙ 2nd-degree AV block and complete AV block are rare presentations of digoxin toxicity.

- Limited effect on the bundle branches: bundle branch block or intraventricular conduction delay are rare features of toxicity.[5]

Extracardiac features of digoxin toxicity include anorexia, nausea and vomiting (in up to 70% of patients), visual disturbances and hyperkalaemia.

Evidence from historical studies, conducted before the introduction of β-blockers for the treatment of heart failure, supports the use of digoxin in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction, particularly in those with advanced symptoms.[6] There is, however, no evidence that digoxin improves survival - it may even worsen outcomes. The Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) Trial, a study of almost 6 800 patients with symptomatic heart failure, left ventricular ejection fraction <45%, and in sinus rhythm, assigned randomly to receive either digoxin or placebo, showed the following results after 3 years of follow-up: (i) there was no difference in survival between the digoxin and placebo groups; (ii) the patients on digoxin had fewer symptoms and were hospitalised less often for heart failure; (iii) patients on digoxin showed a significant increase in non-heart failure deaths, including deaths from arrhythmia, particularly in women; and (iv) lower serum digoxin levels correlated with survival.[7]

It is imperative to identify patients at risk of toxicity and determine their haemodynamic status. In stable patients, withdrawal of digoxin and close monitoring may be sufficient.[2] In unstable patients, identification and treatment of the associated arrhythmia and correction of electrolyte imbalances that may accompany and exacerbate digoxin toxicity are advised.[2] Digoxin-specific human immunoglobulin fragments are indicated in the setting of intractable arrhythmias and haemodynamic compromise.[1,2]

In summary, this case serves as a timely reminder that careful consideration and thought should be given prior to the use of cardiac glycosides. Although frequently used in the treatment of heart failure with low ejection fraction and atrial fibrillation/ flutter, for symptomatic benefit and decreased hospitalisation rates these drugs offer no survival benefit and may be associated with worse outcomes.[6] Close monitoring and dose adjustment are required in elderly patients and those with renal impairment, and when used with other anti-arrhythmic drugs. Indeed, in an article in the Forum section in this edition of SAMJ, Opie[8] states that there are few arguments in favour of the use of digoxin to control rate in atrial fibrillation.

References

1. Yang EH, Shah S, Criley JM. Digitalis toxicity: A fading but crucial complication to recognize. Am J Med 2012;125:337-343. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.09.019] [ Links ]

2. Hauptman PJ, Kelly RA. Digitalis. Circulation 1999;99:1265-1270. [ Links ]

3. Eichhorn EJ, Gheorghiade M. Digoxin. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2002;44:251-266. [ Links ]

4. Gheorghiade M, Adams KF, Colucci WS. Digoxin in the management of cardiovascular disorders. Circulation 2004;109:2959-2964. [ Links ]

5. Fisch C, Knoebel SB. Digitalis cardiotoxicity. J Am Coll Cardiol 1985;5(5 Suppl A):91A-98A. [ Links ]

6. Ntusi NBA, Badri M, Gumedze F, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of familial and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy in Cape Town: A comparative study of 120 cases followed up over 14 years. S Afr Med J 2011;101:399-404. [ Links ]

7. Digitalis Investigation Group. The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med 1997;336:525-533. [ Links ]

8. Opie LH. Digitalis reappraised: Still here today, but gone tomorrow? S Afr Med J 2015;105(2):88-89. [http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.8634] [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

N A B Ntusi

ntobeko.ntusi@gmail.com