Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versão impressa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.104 no.11 Pretoria Nov. 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.8919

REVIEW

PAEDIATRIC HEPATOBILIARY

Liver tumours in children: current surgical management and role of transplantation

A J W Millar

FRCS, FRACS (Paed Surg), FCS (SA), DCH; Emeritus Professor of Paediatric Surgery, University of Cape Town and Red Cross War Memorial Children's Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This article reviews the current surgical management of liver tumours in children in the light of improved chemotherapy, surgical techniques and outcomes from transplantation. It is a principle of management that complete removal of a tumour must be achieved for cure. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy may downstage advanced local disease to enable safe curative tumour resection. When this is not achievable, transplant is indicated. Conventional indications for transplant are unresectable stages 3 and 4 tumours confined to the liver. With the realisation that lifelong immunosuppressive therapy has considerable adverse consequences, there has been a recent trend towards extreme and 'acrobatic' liver resection to avoid transplantation, but still obtain a cure. The current literature is reviewed in the light of these trends and our own experience.

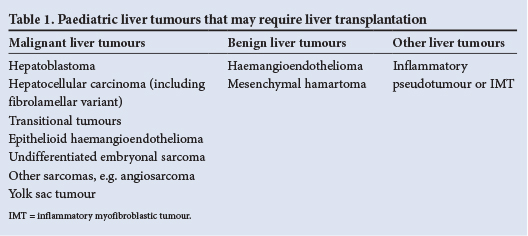

Before embarking on any surgical enterprise with regard to the liver, it is essential to become familiar with the normal anatomy, function and regeneration/repair of the liver as well as the common variants in terms of blood supply (portal and systemic), venous drainage and the intra- and extrahepatic biliary anatomy (Fig. 1).1 Paediatric liver tumours that may require liver transplantation are shown in Table 1.2 , 3

Disease assessment includes full imaging with ultrasound (US) and Doppler evaluation, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging with gadolinium, angiography and cholangiopancreatography. In children who may well receive preoperative chemotherapy, in most cases a diagnostic biopsy is preferred, usually a Trucut needle core, but laparoscopic or open wedge biopsies may be safer with regard to bleeding from the biopsy site. This would seem essential in infants <3 months and in children >3 years of age if there is a normal or near-normal serum α-fetoprotein level.2 , 4 , 5

There are a number of ways to assess and prognosticate the possible outcome of children with liver tumours and specifically with hepatoblastoma, the best known of these is the International Society of Pediatric Oncology (SIOP)'s pretreatment extent (PRETEXT) of disease system, which takes into account the extent of involvement of the four sectors of the liver and also notes extrahepatic growth using the letter V for hepatic vein, P for portal vein, M for metastases and E for extrahepatic lymph nodes.4 , 5 This system has shown good reproducibility with a tendency to overstage, but it is an excellent predictor of survival. Additional information from a histopathological examination of the resected tumour, which would include the tumour's multifocality, vascular invasion and cell type, increases the accuracy of prognosis.6 Indicators of good prognosis are the presence of differentiating mesenchymal elements (i.e. fetal histology), therapy-related extent of necrosis of the resected tumour and quantity of viable mensenchyme (bone, muscle and cartilage).6 An outline of management for hepatoblastoma and other malignant liver tumours is illustrated in Fig. 2.

The principles of surgical management are to remove all of the tumour, and if this cannot be done even after chemotherapy, then transplantation should be considered.3 In Internationale d'Oncologie Pediatrique - Epithelial Liver Study Group 2 (SIOPEL) the results of this conventional approach in standard-risk patients showed a 96% macroscopic resection rate and a 90% event-free survival rate. In those high-risk cases with metastases, vascular invasion and extrahepatic resection, the resection rates were down to 66% and event-free survival was only 47%.5 ,7 In our own series since 1990 at Red Cross War Memorial Children's Hospital, using the SIOPEL 3 protocol of chemotherapy, 44 of 49 patients underwent surgical resection with 41 survivors (83%). Of the 49, 1 was unresponsive to chemotherapy and 4 relapsed; 3 with lung metastases and 4 locally, of which 2 were lymph node-positive at surgery; none was transplanted.

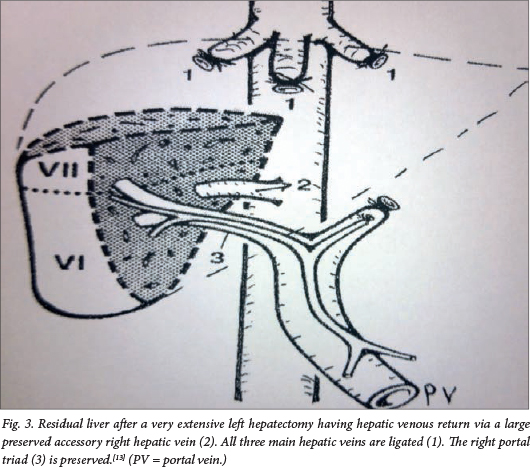

What then is the role of transplantation in our setting of a developing economy and uneven healthcare delivery? Accepted criteria for transplant should be an anatomically unresectable tumour, where complete removal can only be achieved by total hepatectomy (i.e. no extrahepatic residual intra-abdominal tumour).8 The tumour should be chemosensitive and all PRETEXT metastases should be cleared by chemotherapy. SIOP recommends early referral to a transplant surgeon in cases of: (i) multifocal or large solitary PRETEXT IV hepatoblastoma involving all four sectors of the liver; and (ii) unifocal, centrally located tumours involving main hilar structures or main hepatic veins. Because complete tumour resection is a prerequisite for cure, any strategy leading to an increased resection rate will result in an improved survival rate. SIOP advises the more frequent use of orthotopic liver transplant in those patients with tumour burden as described above, as well as the standardisation of techniques for partial liver resection.9 Although SIOP's guidelines should not be seen as final, but rather as a starting point for further discussion between the various national and international liver tumour study groups, it is indeed a moot point as to whether transplantation in our setting should be recommended so precipitously. The short-term results from transplantation are good, with >70% survival in most series (Table 2).4 , 10 Clearly, transplantation should not be considered lightly, as it condemns a child to lifelong immunosuppressive therapy and the risk of graft dysfunction and rejection.11 One should be reminded that the consequences of lifelong immunosuppressive therapy include impairment of renal function owing to a combination of chemotherapy and calcineurin inhibitor drug toxicity, dyslipidaemia, lymphoproliferative disease and other malignancies, e.g. Kaposi sarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, and skin, breast and gastrointestinal cancers.12 It is therefore a reasonable discussion point as to how far one should go in order to avoid transplantation. There is of course the potential for rescue transplant after a failed resection with local recurrence, but the outcomes are less favourable than primary transplantation.4 , 10 One can push the limits of surgery to the extreme in order to completely remove all tumours, even when in conventional terms the tumour may be considered unresectable. Examples include resecting a tumour with adjacent hepatic vein involvement and replacing the vein with a graft. On occasions where the main tumour involves most of the liver but segments 6 and 7 are clear, if there is a large accessory right hepatic vein as described by Baer et al., an extended left hepatectomy including segments 1 - 8 can be performed with preservation of adequate venous outflow via this vein (Fig. 3).13-15

Another extreme surgical concept is extending the hepatic resection with transplantation as an immediate back-up or saftey net should a complete resection, having been embarked on, turn out not to be possible. We did this in a 10-year-old boy with a large central fibrolamellar tumour, performing an extended left hepatectomy with Roux-en-Y drainage of an obstructed right segment 6,7 bile duct with long-term success; the patient was healthy 17 years post resection.16

In chemosensitive tumours, this strategy of resection can be extended to patients with multicentric tumours where satellite tumours in residual liver segments can be separately excised in addition to the main tumour. Good preoperative imaging and intraoperative US is essential to identify all residual tumours. Likewise, when considering removal of a tumour, particularly a large tumour, one must think about the residual volume of liver that will remain and consider staged surgery with initial portal vein occlusion as a strategy to grow residual liver and avoid small-for-size syndrome.17 , 18 Portal vein occlusion may be done as an open procedure, via a laparoscope or by using transhepatic interventional radiography and a variety of embolisation techniques and substances. The definitive surgical resection is carried out 2 - 4 weeks later, after ipsilateral atrophy and contralateral hyperplasia has occurred. The surgical options include resection of all hepatic tumours with an additional >1 cm margin around hepatocellular carcinomas; the other tumours, being chemotherapy sensitive, simply need free tumour margins as preference. The resections available are tumourectomy (non-anatomical), segmentectomy, (segments 4a,b) central resection, hemihepatectomy (right or left liver, along Cantlie's line), extended hepatectomy (right or left), staged resection after portal vein occlusion, ex vivo surgery with autotransplantation and transplantation, which may be primary or as rescue after local recurrence following a previous attempt at curative resection.2 , 10 , 15

Strategies for safe liver resection include protecting the liver during the resection with ischaemic preconditioning, avoiding any venous outflow obstruction from kinking or narrowing of the residual hepatic vein and reduction of postresection hyperperfusion, which may lead to congestion. This is done using a variety of techniques to reduce inflow of blood to the much smaller residual liver, which include splenic artery ligation, partial portosystemic shunting and the use of β-blockers such as propranolol. In the postoperative phase liver support in the intensive care unit is important. This may include the use of somatostatin, acetylcysteine, pentoxifylline and prostaglandin infusion, in addition to supplementing of clotting factors with fresh frozen plasma and vitamin K. Early commencement of enteral feeding is also trophic to the liver, but inevitably increases portal blood flow.18

There are, of course, instances where tumour resection is not possible and transplantation is the only option. These would even include some benign tumours, such as a very extensive haemangioendothelioma not responding to treatment with β-blockers, chemotherapy or angioembolisation.4 Causes of death in children transplanted for liver tumours are predominantly tumour recurrence (60% for hepatoblastoma and 86% for hepatocellular carcinoma); technical or immunosuppression/rejection-related complications are similar to those in children receiving liver transplants for other diseases.12

Conclusion

The best results are achieved by a combination of elective resection in well-selected cases, transplantation and rescue transplantation. Centres of hepatobiliary surgery should offer both extended hepatic resection and transplantation.10Extreme resections should be considered as an option, particularly where access to transplantation is suboptimal and where access to diligent long-term follow-up is challenging. If transplantation is the only option, then timing of the transplant is crucial. Ideally transplantation should be between courses of chemotherapy, with some post-transplant chemotherapy possible. Living donor transplant is preferred, because the timing of the transplant can be planned and the graft is usually of superior quality when compared with a deceased donor graft.

REFERENCES

1. Kelly D. Chapter 1. Structure, function and repair. In: Baumann U, Brown R, Millar A. Diseases of the Liver and Biliary System. 3rd ed. Chichester, John Wiley & Sons, 2008. [ Links ]

2. Emre S, Umman V, Rodriguez-Davalos M. Current concepts in pediatric liver tumors. Pediatr Transplant 2012;16(6):549-563. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3046.2012.01704.x] [ Links ]

3. Stringer MD. The role of liver transplantation in the management of paediatric liver tumours. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2007;89(1):12-21. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1308/003588407X155527] [ Links ]

4. Otte JB, Pritchard J, Aronson DC, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatoblastoma: Results from the International Society of Pediatric Oncology (SIOP) study SIOPEL-1 and review of the world experience. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2004;42(1):74-83. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pbc.10376] [ Links ]

5. Czauderna P, Otte JB, Aronson DC, et al. Guidelines for surgical treatment of hepatoblastoma in the modern era: Recommendations from the Childhood Liver Tumour Strategy Group of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOPEL). Eur J Cancer 2005;41(7):1031-1036. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2005.02.004] [ Links ]

6. Davies JQ, de la Hall PM, Kaschula ROC, et al. Hepatoblastoma: Evolution of management and outcome and significance of histology of the resected tumor. A 31-year experience with 40 cases. J Pediatr Surg 2004:39(9):1321-1327. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.05.020] [ Links ]

7. Tiao GM, Bobey N, Allen S, et al. Current management of hepatoblastoma: A combination of chemotherapy, conventional resection, and liver transplantation. J Pediatr 2005;146(2):204-211. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.09.011] [ Links ]

8. Austin MT, Leys CM, Feurer ID, et al. Liver transplantation for childhood hepatic malignancy: A review of the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database. J Pediatr Surg 2006;41(1):182-186. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.10.091] [ Links ]

9. Perilongo G, Shafford E, Maibach R, et al. Risk-adapted treatment for childhood hepatoblastoma: Final report of the second study of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology - SIOPEL 2. Eur J Cancer 2004;40(3):411-421 [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2003.06.003] [ Links ]

10. Malek SR, Shah MM, Atri P, et al. Review of outcomes of primary liver cancers in children: Our institutional experience with resection and transplantation. Surgery 2010;148(4):778-782. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2010.07.021] [ Links ]

11. Kelly DA, Bucuvalas JC, Alonso EM, et al. Long-term medical management of the pediatric patient after liver transplantation: 2013 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Society of Transplantation. Liver Transpl 2013;19(8):798-825. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/lt.23697] [ Links ]

12. Fung JJ, Jain A, Kwak EJ, Kusne S, Dvorchik I, Eghtesad B. De novo malignancies after liver transplantation: A major cause of late death liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2001;7(11 Suppl 1): s109-s118. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/jlts.2001.28645] [ Links ]

13. Baer HU, Dennison AR, Maddern GJ, Blumgart LH. Subtotal hepatectomy: A new procedure based on the inferior right hepatic vein. Br J Surg 1991;78(10):1221-1222. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800781024] [ Links ]

14. Baertschiger RM, Ozsahin H, Rougemont AL, et al. Cure of multifocal panhepatic hepatoblastoma: Is liver transplantation always necessary? J Pediatr Surg 2010;45(5):1030-1036. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.01.038] [ Links ]

15. Lautz TB, Ben-Ami T, Tantemsapya N, Gosiengfiao Y, Superina RA. Successful nontransplant resection of POST-TEXT III and IV hepatoblastoma. Cancer 2011;117(9):1976-1983. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25722] [ Links ]

16. Millar AJ, Hartley P, Andronikou S, Spearman W, Kahn D. Extended hepatic resection with transplantation back-up for an 'unresectable' tumour. Paediatr Surg Int 2001;17(5-6):378-381. [ Links ]

17. De Baere T, Roche A, Elias D, Lasser P, Lagrange C, Bousson V. Preoperative portal vein embolization for extension of hepatectomy indications. Hepatology 1996;24(6):1386-1391. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/jhep.1996.v24.pm0008938166] [ Links ]

18. Clavien PA, Petrowsky H, DeOliveira ML, Graf R. Strategies for safer liver surgery and partial liver transplantation. N Engl J Med 2007;356(15):1545-1559. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra065156] [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

A J W Millar

alastair.millar@uct.ac.za