Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versión impresa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.104 no.7 Pretoria jul. 2014

FORUM

OPINION

The RWOPS debate - yes we can!

A TaylorI; D KahnII

IAllan Taylor is a neurosurgeon working at Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa

IIDelawir Kahn is Head of the Department of Surgery at the University of Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Remunerated work outside of public service (RWOPS) has largely been seen in a negative light. This is partly a result of the Public Service Commission review undertaken in 2004, but attitudes are also shaped by unsubstantiated reports of abuse. There are, however, potential advantages for both patients and doctors if RWOPS is done without neglecting public sector service and academic commitments. We explore some of the issues around controlling RWOPS, and the experience with this in the Department of Surgery at the University of Cape Town, South Africa.

Remunerated work outside of public service (RWOPS) for doctors has been controversial since its inception. It was introduced to improve remuneration for state-employed doctors, and thereby retain doctors in the public sector. There are, however, other benefits of RWOPS, which are outlined below.

Recently the focus has been on abuse of the system by some doctors who spend unreasonable amounts of time treating private patients and neglecting their public service obligations.[1,2] Evidence for this abuse is almost all anecdotal. The Public Service Commission (PSC) conducted an enquiry into RWOPS in Gauteng Province, South Africa, in 2004.[3] This report was largely negative and stated that, among other abuses, more than 50% of state-employed specialists owned private clinics and that 'sick leave' was taken in order to conduct private work. It should be noted that this report was based on questionnaires completed by only 20 of a total of over 700 doctors employed at the institutions under review. A more recent review (unpublished) of RWOPS in Mthatha, Eastern Cape Province, was similarly negative and showed that one in four specialists employed at the Nelson Mandela academic complex of Walter Sisulu University earned R6 500 - R126 000 over a 6-month period by doing private work. This was felt to be excessive and added to perceptions of abuse, prompting the Minister of Health's statement that 'patients are dying because of specialist greed'.[4]

Abuse of RWOPS

Abuse of RWOPS by some doctors who spend unreasonable amounts of time treating private patients and neglect their public service obligations needs to be taken seriously. The PSC report made a number of recommendations aimed at improving the RWOPS policy framework with tighter management control. It concluded that attitudes of staff should be directed towards serving their communities, and also stated that 'constant improvement of an ethical culture requires that appraisal systems be utilised in order to recognise and reward ethical behaviour, while unethical behaviour continues to be swiftly and visibly punished'.[3]

Potential advantages of RWOPS

RWOPS was introduced at a time when many staff, particularly young, newly qualified specialists, were leaving the public healthcare system because of inadequate salaries and frustration with budget cuts, inadequate equipment and service restrictions. The intention was to allow doctors to supplement their income, and to have access to modern equipment and resources so that their skills could continue to be improved, all of which would allow them to remain in the public system. Potentially, RWOPS stood to increase practitioners' exposure to a broader spectrum of disease and/or a greater number of focused cases, and to open up research opportunities and broaden the teaching platform for undergraduate and postgraduate students.

These are, of course, mostly advantageous to practitioners and not necessarily to patients. However, there are advantages to both public and private patients in allowing this crossover practice. Private patients benefit from the evidence-based practice that is part of academic medical practice and from accessing super-specialist services, available only in large academic hospitals. The advantage for public patients is improved care through retention of experienced staff who are not lost to the private sector. The PSC report hints at a more subtle advantage by suggesting that staff should be directed towards serving their communities. How much better could our public healthcare facilities be if service levels approached those of private facilities? Perhaps exposure to the private culture of efficient, professional and polite service could diffuse into our public hospitals by staff crossing between institutions.

Improving RWOPS control

A national policy that complies with appropriate public service regulations is required. The framework should set out the responsibilities of staff with regard to their public service commitments, the restrictions pertaining to private work, and how public sector and private sector duties will be monitored. This framework will require flexibility if it is to apply to all provinces and institutions, as service loads and requirements to conduct research or teach will vary between hospitals.

There are currently four major issues in respect of how RWOPS is performed:

- How many hours of RWOPS? Most doctors in medical officer or specialist posts are contracted to work 56 hours per week. Forty hours are considered to be for normal duties and 16 hours are for overtime work. In the Western Cape Province, 16 hours per week of private work is currently allowed, although in the Department of Surgery at the University of Cape Town (UCT) this is further restricted to 8 hours. Eight hours per week was considered by colleagues in the Department to be reasonable.

- When can RWOPS be performed? When private work can be performed is a more thorny issue, with some feeling that it should only be done after normal working hours or over weekends. The assumption underlying this is that doctors' hours are regular. Although true for some specialties, this is not so for many others, where working hours are determined by service demands and as patients present, often acutely. In the Western Cape this has been dealt with through a 'work plan', which requires that 40 hours per week be worked in public service between 06h00 and 19h00. As long as this requirement is met, doctors may undertake their private work at any time. Overtime commitments must also be detailed in the work plan.

- Where may RWOPS be performed? Currently private work is not allowed to be performed in any state hospital or involve use of any state equipment. Some institutions (UCT, the University of the Free State and the University of the Wit-watersrand) are fortunate in having associated private hospitals where RWOPS can be done. Many doctors, however, have no alternative but to work in other private hospitals. Splitting working time between remote hospitals is not ideal, because it affords little chance for managers to oversee and control staff. A solution might be public-private partnerships where public hospital managers or universities have some oversight of doctors working in private institutions.

- Should income from RWOPS be limited? Income is a complex issue, as there are currently no ethical tariffs and disparities in practice costs are wide. For instance, malpractice cover currently runs at around R330 000 per annum for high-risk practice and only R16 080 for low-risk practice. It is unfair to judge doctors as greedy based on a gross income. It is also unreasonable to assume that all RWOPS-generated funding is used for cars, expensive homes and holidays. Many doctors use this money to support research efforts and departmental funds, and to pay for attendance at congresses.

A framework will need to deal with all of these issues, and ideally should move towards an output-based monitoring system rather than a purely restrictive system.

RWOPS in the Department of Surgery at UCT

The Department of Surgery at UCT established a RWOPS Committee (Profs D Kahn, J Brink, E Panieri and A Taylor) to monitor RWOPS activities in the Department. Each staff member has to apply annually for the privilege of performing RWOPS. In the application process the practitioner has to produce a detailed work plan that outlines all activities in both the state and private sectors, i.e. ward rounds, outpatient clinics, theatre, teaching, administration, etc. The application has to be signed off by the practitioner's supervisor, the Head of the Division and the Head of the Department before being sent to the CEO of the hospital for approval.

In principle, RWOPS is encouraged but should be limited to 8 hours per week. Furthermore, doctors are encouraged to perform RWOPS in the UCT Private Academic Hospital, which is on site, while off-site practices are discouraged. Practitioners are allowed to perform RWOPS during normal working hours, but outside of the 40 hours of normal duty.

The 2012 RWOPS audit

Aware of the criticism of RWOPS abuses, directed mostly at surgeons, the Department of Surgery RWOPS Committee undertook a review of RWOPS practice in the Department in 2012.

Method

All full-time staff, including division heads, and a registrar and student sample were interviewed by the RWOPS Committee and asked to comment on the following issues:

- perception that the Department abuses RWOPS

- perception that some divisions abuse RWOPS

- impact on full-time commitments

- own RWOPS practice.

Of 57 full-time staff members, five were excluded from the process because they were retiring or not available; 52 were interviewed, including four surgeons who had voluntarily taken part-time positions, or had given up their overtime work and pay because they wished to spend more than 8 hours per week doing private work.

Results

Of the 48 interviewed who were in full-time positions, 14 (29.2%) performed no private work.

While a few practitioners felt that RWOPS was not beneficial, the majority believed that it was, citing maintenance of skills, financial reward, exposure to a different spectrum of patients/disease, and opportunity for registrar training as reasons.

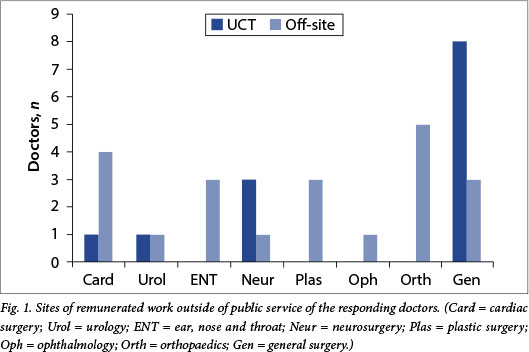

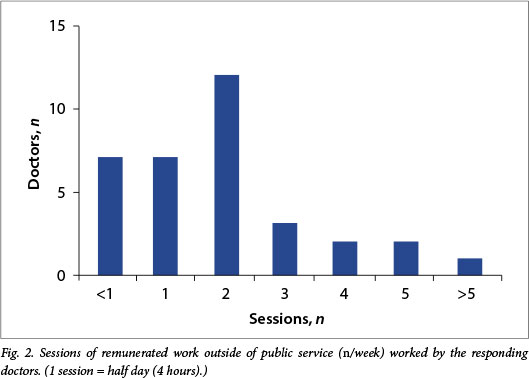

Of specialists who performed private work, 13 practised only at the UCT Private Academic Hospital and 21 worked at another private hospital (Fig. 1). Of the 34 fulltime staff performing RWOPS, 26 (76.5%) performed 8 hours or less of private work per week, with eight undertaking more than this (Fig. 2). More than 83% of the 48 fulltime staff members interviewed were not performing RWOPS or spent 1 day or less doing private work.

The registrars who were interviewed did not have negative comments about consultants doing private work, and many felt that they had benefited through exposure to operations not routinely performed in public hospitals.

Conclusion

Following this audit, the Department decided to continue with an annual review of RWOPS activities and to limit private practice to two half-day sessions a week. No new consultations or procedures could be undertaken beyond this limit, although urgent problems arising with inpatients could be attended to. Doctors were also encouraged to undertake their RWOPS at the UCT Private Academic Hospital.

2013 RWOPS audit

As part of the ongoing monitoring process, the RWOPS Committee repeated their audit of RWOPS activities of all members of the Department.

Method

An online survey of RWOPS practice of all specialists in the Department was undertaken. They were asked to populate an Excel spreadsheet detailing fixed full-time commitments and fixed times allocated to RWOPS. They also had to submit a list of all private activities, including dates and times of consultations and procedures, during a 2-week period in September.

Results

Thirty-two replies were received. Almost all staff had complied with their agreed work plans, performing less than 8 hours of private work per week. Only two doctors did more than 8 hours of private work per week between the hours of 07h00 and 19h00, one of whom had given up overtime pay in an agreed contract allowing more RWOPS work.

Two consultants each performed 1 hour per week of private work outside of their agreed work plan when they had to treat emergency cases. Six doctors scheduled some of their RWOPS work after 19h00 on weekdays, or over weekends, in order not to conflict with full-time commitments. Thirteen doctors (40.6%) did no overtime work during the period under review.

Conclusion

RWOPS is responsibly performed in the Department, with very few deviations from submitted work plans. Outstanding replies are being followed up and random audits are still to be done on submitted data.

The original intent of RWOPS remains valid. It is important to retain the skills of experienced staff in the public sector, and RWOPS helps to achieve this end. However, RWOPS can only continue if public sector work is competently dealt with and remains the primary responsibility of public sector doctors. The key to achieving this is strong management to ensure and enforce a fair RWOPS dispensation.

1. Goldstein L. Thieves of the state. S Afr Med J 2012;102(9):719. [http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.6165] [ Links ]

2. Caldwell R. Thieves of the state - a response. S Afr Med J 2012;102(10):775. [http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.6301] [ Links ]

3. Public Service Commission. Remunerative work outside of Public Service. 2004 report. http://www.psc.gov.za/documents/2004/remunerati ve_woroutside_psc.pdf (accessed 30 November 2013). [ Links ]

4. Bateman C. RWOPS abuse - Government's had enough. S Afr Med J 2012;102(12):899-901. [http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.6481] [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

A Taylor

(allan.taylor@uct.ac.za)

Accepted 4 April 2014