Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.104 n.5 Pretoria May. 2014

CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION

ARTICLE

Stigma, survivorship and solutions: Addressing the challenges of living with breast cancer in low-resource areas

M MutebiI; J EdgeII

IMB ChB, MMed (Surg). Surgical Oncology Fellow, Department of Endocrine and Surgical Oncology, Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa, Aga Khan University Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya, and Research Advocacy, African Organisation for Research and Treatment in Cancer (AORTIC), Cape Town, South Africa

IIMBBS, BSc, FRCS, MMed (Surg). Netcare Christiaan Barnard Memorial Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Breast cancer in developing nations is characterised by late diagnosis. The causes are multifactorial and many are addressed in other articles in this edition of CME. Breast cancer is also seen in younger women. The late-presentation trend is slowly changing in some areas, and an increasing number of women are presenting with early disease. These patients, if managed appropriately, have a more favourable prognosis. As a result, developing nations must now begin to consider the concerns of breast cancer survivorship. In developed countries, there are a number of organisations that support breast cancer survivors. In this article, we highlight some of the psychosocial aspects of living with breast cancer in low-resource areas.

Age at presentation

Newman[1] demonstrated that the overall mean age at which African women present with breast cancer is 35 - 45 years, 10 - 15 years earlier than their Caucasian counterparts.[2] A 3-year retrospective review of 374 breast cancer patients in Kenya showed a median age of 44 years at presentation;[2] only 26 of 250 (10.4%) had early breast cancer. Of 250 patients reviewed by Adebamowo et al.,[3]72.8% presented with advanced breast cancer (Manchester stage III and IV disease). In South Africa, no national data exist. However, individual breast centres increasingly report their experience with early breast cancer.[4-6]

Stigma

Stigma refers to the attachment of negative connotations to a diagnosis. The Livestrong Foundation Report determined that stigma is an important part of cancer diagnosis.[7] Studies in African American women show that fatalism, stigma and privacy are some of the key factors influencing non-attendance in regions where national screening programmes exist.[8] These are accentuated in low-resource environments where facilities do not exist.

Patients in low-resource settings face unique challenges in having to cope with breast cancer. Not only do they have to deal with the emotional impact of a cancer diagnosis, but also with the additional constraints of poverty, lack of access to care and dependence on their partners for financial support.

A study of 81 women with breast cancer in Nigeria showed that married African women have significant emotional, physical and social problems following primary treatment of breast cancer.[9] Of the 81 patients included in the study, 38.3% had divorced or separated 3 years after therapy compared with the national average of 2.6%.

Survivorship

The American College of Surgeons classifies survivorship as >5 years since the initial diagnosis of cancer.[10] Little has been written on survivorship in low- and middle-income countries owing to the frequent lack of national cancer registries and poor patient follow-up. Hayanga and Newman[11] described a high incidence/mortality ratio of breast cancer in women on the African continent, 1:2 compared with 1:5 among white American women. While these low ratios may be due to late presentation, more vigilant follow-up of patients in the immediate post-treatment phase could potentially identify other key contributing factors.

The quality of life (QOL) of patients who survive cancer may be positively or negatively affected.[12] QOL is defined as the perception of well-being that arises from an individual's satisfaction or dissatisfaction with those aspects of life that are important to the person.[13] QOL may differ depending on the stage of breast cancer, the treatment modalities and the survivorship after the initial treatment phase. Breast cancer patients are at an increased risk of developing physical and psychological conditions that affect their overall QOL.[14] Lack of knowledge of recovery patterns and evidence-based guidelines for follow-up care may result in persistent and late effects of cancer treatment.[14]

Uncertainty remains a major concern among patients with breast cancer and has a strong impact on their coping behaviour and QOL.[13] Uncertainty is defined as the inability of a person to understand the meaning of illness-related events such as the disease process, treatment, or hospitalisation.[15] It develops if the patient has no understanding of the disease process, either due to lack of knowledge, complex treatment regimens or the unpredictable nature of the disease. This may be exacerbated in low-income settings where resource constraints may hamper effective management of tumours. Concerns over disease recurrence, side-effects of treatment and threat of death and dying continue to have significant implications on a patient's functional status.[16]

Health-related QOL encompasses the physical, psychological and social functioning of patients.[17] The QOL model for cancer patients, which was initially proposed by Ferrell,[18] consists of four dimensions, i.e. physical, psychological, social and spiritual well-being. Physical dimensions infer that the patient can continue with activities of daily living. The psychological domain emphasises a sense of control over the disease and its threat to life. The social domain refers to an individual's ability to re-integrate and maintain meaningful relationships, whereas the spiritual domain requires that an individual maintains hope and an understanding of their disease[18]

QOL may be determined by the health, professional and family environment.[19] These factors may be further modified as a result of the disease and its treatment.[20] QOL plays a very important role in breast cancer survivors, and the overall physical, psychosocial and spiritual considerations need to be addressed. Physical limitations, such as the impaired ability to return to work, and psychological distress and uncertainty over the future, have implications on the individual's QOL.

Survivorship in resource-poor settings

Survivorship in developing countries constitutes a newly emerging concept. With the transition to survivorship come new concerns along the Ferrell domains,[18] all of which may warrant interpretation in a regional context. Breast cancer survivors encounter unique socioeconomic challenges and a lack of an established support system.

There are very little data on breast cancer survivorship in low-income countries. Therefore, not much is known about factors affecting the population, and the absence of a national cancer register makes patient follow-up difficult.

Solutions

Regardless of the patient's environment, the US-based Institute of Medicine of the national academies recommends that a comprehensive care plan be developed for cancer survivors (Tables 1 and 2). There is a need to optimise ways to ameliorate the overall level of suffering and to remove the stigma attached to breast cancer. Practical strategies in low-resource environments include increasing breast cancer awareness, promoting cancer advocacy, strengthening the survivorship base by providing positive role models who have survived cancer, and the development of an effective cancer navigation system.

Breast cancer awareness is an attempt to increase knowledge and reduce stigma. It aims to encourage women to be more aware of their breasts, thereby promoting earlier presentation and diagnosis. Breast cancer advocacy refers to the strategies employed predominantly by breast cancer survivors and well-wishers towards treatment and support. Survivorship refers to holistic living, and cancer navigation to the development of a support and referral system to ensure that all cancer patients receive optimal care.

Breast cancer awareness

Breast health awareness can contribute towards reducing the stigma of the diagnosis and increasing earlier presentation. Stockton et al.[21] in the 1980s were able to demonstrate an earlier presentation of breast disease due to an increase in media campaigns. Health-seeking behaviour of communities is very important. Lack of community involvement has led to initiatives not being readily adopted, as illustrated by Pisani et al.[22] in Asia. Innovative strategies are required to define the barriers to health-seeking behaviour and to try to overcome them.

Community healthcare workers may be used to determine barriers to access to healthcare. Studies by Abuidris et al.[23] in Sudan, using healthcare workers who were educated in breast health promotion and then returned to their communities, helped to decrease the stigma of breast pathology and provide a forum for safe communication of healthcare problems with familiar people. Similar studies in Bangladesh by Ginsburg et al.,[241 where community healthcare workers shared testimonials of successfully treated patients with the general public, helped to decrease the stigma of breast cancer.

Community 'buy in' is key and a synergistic dialogue should be maintained between communities and breast cancer awareness organisers. Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) play an active role in breast cancer awareness. In developed countries, organisations such as the Susan G Komen Foundation and the Avon Foundation have increased awareness of breast cancer internationally. In South Africa, a number of breast cancer NGOs exist. The recent creation of a national coalition of these NGOs should be commended, as it is a model designed to effect change.

Creation of a survivorship model

Involving key cancer survivors in a community can contribute towards removing the stigma of cancer. Positive role models with whom patients can identify can go a long way towards removing the myths surrounding cancer - in Uganda, studies have demonstrated the benefit of using patients' spouses and cancer survivors.[25]

Survivorship navigation

Alongside the use of positive role models, the creation of a successful navigation programme has dramatically increased attendance in low-resource areas. Raj et al.[26] described a decrease in the stage at presentation and an improvement in clinical treatment adherence when using navigators in underserved areas of the USA, which may reflect the situation in low-resource environments. The adaptation of a survivorship navigation model to our local scenario could have a positive impact in the region. The purpose of survivorship navigation is to assist with mitigating barriers that survivors may experience in accessing survivorship services and attaining a good QOL.[27] The use of community healthcare workers for navigation has also been successfully demonstrated by Ginsburg et al.[24] in Bangladesh.

Call for cancer advocacy

There is a role for cancer advocacy. It employs a multipronged approach with different arms of advocacy contributing to the overall advancement of cancer knowledge. Educational advocacy involves improving cancer awareness among patients, their families and the public by using different modalities, such as the print media and radio. Social gatherings such as weddings, fundraising events, preplanned town meetings or worship gatherings can all be employed as platforms where this knowledge can be disseminated.[28]

Community outreach advocacy involves a bidirectional dialogue between the target community and cancer advocates. An assessment is done to determine the cancer needs of the community and how advocates can address these concerns. Dissemination of information back to a community and working with key stakeholders help to develop an effective community advocacy model. The community feels engaged in the process, and advocates avoid imposing their perceived plans on a community.[28]

Support advocacy involves trying to address the concerns of patients and families living with cancer. This is of particular importance, especially in newly diagnosed patients, who may frequently be bewildered by the implications of a cancer diagnosis. The African Organisation for Research and Treatment in Cancer (AORTIC) support advocacy working group defines cancer support as connecting patients, families and caregivers for help, hope, and inspiration throughout cancer management and need.'281 This support attempts to ensure holistic living of patients and could involve emotional support, financial advice, and nutritional recommendations. Support advocacy aims to address all of Ferrell's domains of concern.[18]

Research advocacy involves ensuring that community-relevant research is carried out. This demands a continuous assessment of the priorities of cancer patients and partnerships with scientists for active involvement in grant proposals and research. It may involve sitting on the medical ethics/institutional review boards of research facilities to ensure that the patients' voice is heard.

Political advocacy involves liaising with stakeholders to ensure that policy affecting cancer is enacted, and collaborating with legislators to ensure that policies that facilitate optimal cancer care are prioritised. Fundraising advocacy involves innovative ways of raising funds to support local cancer initiatives, which may involve local businesses or community stakeholders.[28]

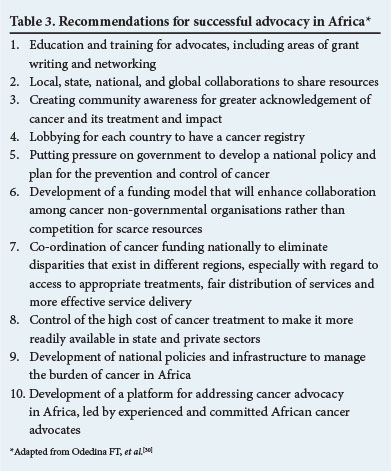

All these arms of advocacy are aimed at increasing the visibility of cancer patients' concerns. The founding of an African consortium of cancer advocates in 2011 and their conclusions for furthering cancer care in the region are a step in the right direction (Table 3). The recent creation of a national breast cancer advocacy group, Advocates for Breast Cancer (ABC), marks a promising new chapter in the approach to cancer care in South Africa.

As clinicians, we have frequently had a 'hands-off' approach to advocacy. As part of a multidisciplinary approach, we are opinion leaders in our field and can do more towards encouraging cancer advocacy. Perhaps, with the increasing burden of cancer, it may be time to review for whom the cancer advocacy bell tolls.

References

1. Newman LA. Breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: How does it relate to breast cancer in African-American Women? Cancer 2005;103(8):1540-1550. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20978] [ Links ]

2. Othieno-Abinya N, Nyabola H. Post-surgical management of patients with breast cancer at Kenyatta National Hospital. East Afr Med J 2002;79:156-162. [http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/eamj.v79i3.8897] [ Links ]

3. Adebamowo CA, Adekunle OO. Case-controlled study of the epidemiological risk factors for breast cancer in Nigeria. Br J Surg 1999;86:665-668. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01117.x] [ Links ]

4. Mannell A. Breast-conserving therapy in breast cancer patients - a 12-year experience. South African Journal of Surgery 2005;43(2):28-32. [ Links ]

5. Edge J. A review of patient demographics, disease profile and management of women with breast cancer seen in private practice in Cape Town. 40th Annual Meeting of the Surgical Research Society of Southern Africa, 12 - 13 July 2012, Stellenbosch, South Africa. [ Links ]

6. Asbury A, Benn CA. Microinvasion in ductal carcinoma in situ: Prediction and prognostications. 37th Annual Meeting of the Surgical Research Society of Southern Africa, 25 - 26 June 2009, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. [ Links ]

7. Neal C, Beckjord EB, Rechis R. Cancer Stigma and Silence Around the World: Livestrong Foundation Report 2007. http://www.livestrong.org/What-We-Do/Our-Approach/Reports-Findings/Cancer-Stigma-and-Silence-Around-the-World (accessed 15 March 2014). [ Links ]

8. Ndukwe EG, Williams KP, Sheppard V. Knowledge and perspectives of breast and cervical cancer screening among female African immigrants in the Washington DC metropolitan area. J Cancer Educ 2013;28(4):748-754. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13187-013-0521-x] [ Links ]

9. Odigie VI, Tanaka R, Yusufu LM. Psychosocial effects of mastectomy on married African women in North western Nigeria. Psycho-Oncology 2010;19:893-897. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.1675] [ Links ]

10. Mols F, Vingerhoets AJ, Coebergh JW, van de Poll-Franse LV. Quality of life among long-term breast cancer survivors: A systematic review. Eur J Cancer 2005;4:2613-2619. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2005.05.017]

11. Hayanga AJ, Newman LA. Investigating the phenotypes and genotypes of breast cancer in women with African ancestry: The need for more genetic epidemiology. Breast 2007;87:551-568. [ Links ]

12. Chopra I, Khalid MK. A systematic review of quality of life instruments in long-term breast cancer survivors. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2012;10:14. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-10-14] [ Links ]

13. Sammarco A. Comparison of QOL in younger and older breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nursing 2009;32(5):347-356. [ Links ]

14. Knobf MT. Psychosocial responses in breast cancer survivors. Semin Oncol Nurs 2007;23:71-83. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2006.11.009] [ Links ]

15. Mishel M. Reconceptualization of the uncertainty in illness theory. J Nurs Scholarsh 1990;22(4):256-262. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.1990.tb00225.x] [ Links ]

16. Sikka M. I Am Not a Hero: I Survived Breast Cancer, Stay Vigilant, and Live in the 'In Between. http://www.everyday health.com/columns/hear-me-out/i-am-not a hero-i survived-breast.cancer (accessed 15 March 2014). [ Links ]

17. Bowling A. What things are important in people's lives? A survey of the public's judgments to inform scales of health related quality of life. Soc Sci Med 1995;41:1447-1462. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00113-L] [ Links ]

18. Ferrell BR. The quality of life: 1,525 voices of cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 1996;23:907-916. [ Links ]

19. Padilla GV, Ferrell B, Grant MM, Rhiner M. Defining the content domain of quality of life for cancer patients with pain. Cancer Nursing 1990;13:108-115. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00002820-199004000-00006] [ Links ]

20. Montazeri A. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: A bibliographic review of the literature from 1974 to 2007. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2008;27:32. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1756-9966-27-32] [ Links ]

21. Stockton D, Davies T, Day N, McCann J. Retrospective study of reasons for improved survival in patients with breast cancer in East Anglia: Earlier diagnosis or better treatment? BMJ 1997;314:472-480. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.314.7079.472] [ Links ]

22. Pisani P, Parkin DM, Ngelangel C, et al. Outcome of screening by clinical examination of the breast in a trial in the Philippines. Int J Cancer 2006;118:149-154. [ Links ]

23. Abuidris DO, Elsheik A, Ali M. Breast-cancer screening with trained volunteers in a rural area of Sudan: A pilot study. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:363-370. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70583-1] [ Links ]

24. Ginsburg OM, Chowdhury M, Wu W, et al. An mHealth model to increase clinic attendance for breast symptoms in rural Bangladesh: Can bridging the digital divide help to close the cancer divide? Oncologist 2014;19:177-185. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0314] [ Links ]

25. Koon KP1, Lehman CD, Gralow JR. The importance of survivors and partners in improving breast cancer outcomes in Uganda. Breast 2013;22:138-41. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2012.12.017] [ Links ]

26. Raj A, Ko N, Battaglia T, Chabner BA, Moy B. Patient navigation for underserved patients diagnosed with breast cancer. Oncologist 2012;17:102-103. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0191] [ Links ]

27. Pratt-Chapman M, Simon MA, Patterson AK, Risendal BC, Patierno S. Survivorship navigation outcome measures: A report from the ACS patient navigation working group on survivorship navigation. Cancer 2011;117(Suppl 15):3575-3584. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26261] [ Links ]

28. Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, eds. Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2006. [ Links ]

29. Adler N, Page A, eds. Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2008. [ Links ]

30. Odedina FT, Asante-Shongwe K, Kandusi E, et al. The African Cancer Advocacy Consortium: Shaping the path for advocacy in Africa. Infectious Agents and Cancer 2013;8(Suppl 1):S8. http://www.infectagentscancer.com/content/8/S1/S8 (accessed 10 March 2014). [ Links ]

Corresponding author:

Corresponding author:

M Mutebi

(mcmutebi@yahoo.com)