Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versión impresa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.104 no.5 Pretoria may. 2014

CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION

REVIEW

The challenges of managing breast cancer in the developing world - a perspective from sub-Saharan Africa

J EdgeI; I BuccimazzaII; H CubaschIII; E PanieriIV

IMBBS, BSc, FRCS, MMed (Surg). Netcare Christiaan Barnard Memorial Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa

IIMB ChB, FCS (SA), FACS. Department of Surgery, Nelson Mandela School of Medicine, Durban, South Africa

IIIMB ChB, FCS (SA). Department of Surgery, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IVMB ChB, FCS (SA). Department of Surgery, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Communicable diseases are the major cause of mortality in lower-income countries. Consequently, local and international resources are channelled mainly into addressing the impact of these conditions. HIV, however, is being successfully treated, people are living longer, and disease patterns are changing. As populations age, the incidence of cancer inevitably increases. The World Health Organization has predicted a dramatic increase in global cancer cases during the next 15 years, the majority of which will occur in low- and middle-income countries. Cancer treatment is expensive and complex and in the developing world 5% of global cancer funds are spent on 70% of cancer cases. This paper reviews the challenges of managing breast cancer in the developing world, using sub-Saharan Africa as a model.

Communicable diseases are the major cause of mortality in lower-income countries. Two-thirds of the world's HIV population live in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and 75% of global deaths due to this disease occur in this region.[1] As a result, both local and international resources have been channelled towards addressing the impact of communicable diseases. However, there is evidence that this pattern of disease burden in low-income countries (LICs) is changing, as HIV is being successfully treated and people are living longer.

Cancer predominantly affects the older population. As the life expectancy in LICs increases, the incidence of cancer will increase. The World Health Organization (WHO) has predicted a dramatic rise in the global number of cancer cases in the next 15 years, the majority of which will be in LICs and middle-income countries (MICs). It has been predicted that by 2020 there will be 17 million new cancer cases, and that by 2050 this figure will be 24 million. Of these cases, 70% will be in the developing world.[2]

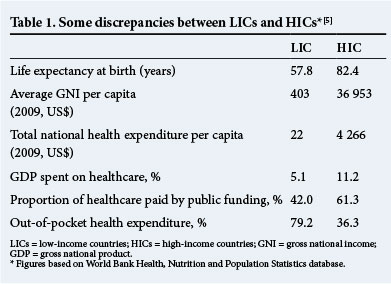

The treatment of cancer is expensive and complex. In the USA, more than US$120 billion per year is spent on cancer care.[3,4] This is in stark contrast to the developing world, where 5% of global cancer funds are spent on 70% of the cancer cases (Table 1).

In LICs, the delivery of healthcare is hampered by many socioeconomic factors such as poor nutrition, sanitation, literacy and transport, and is compounded by the lack of medical personnel, poor infrastructure and health policies.

The sub-Saharan Africa perspective

According to the WHO, SSA comprises 13% of the world's population. It also carries 24% of the global disease burden, but has only 1% of the global financial resources to do this. SSA's demographics show a young population of whom 40% are <15 years of age. The mortality figures mirror this -80% of all deaths occur in those who are <60 years old. Conversely, in high-income countries (HICs), 80% of deaths occur in those >60 years of age.[6]

The cancer patterns seen in SSA are different from those in the developed world. Although the overall cancer incidence is lower than in developed countries, relatively more malignancies are seen in children and young people. The commonest malignancies in women are cervical and breast cancer.

There is a lack of medical personnel in SSA. The WHO recommends that ideally the physician:population ratio should be 50:100 000, while in Africa it is only 18:100 000. More than 100 medical schools in SSA were surveyed; half of these reported losing 6 - 8% of their staff in the past 5 years.[7]

While the management of cancer requires specialist knowledge, there is a paucity of all types of specialists in SSA. In addition, there are discrepancies within the SSA region, with South Africa (SA) faring better than its neighbours. In this regard, it should be noted that SA is essentially an MIC, but due to the gross disparities in socioeconomic class it is effectively both an HIC and a LIC. For example, in Uganda there are 10 specialist anaesthetists[8] compared with 800 in SA (I Buccimazza - unpublished data, 2008) (Fig. 1).

Not only are specialist resources scarce, but support services and essential medications are also lacking. Half of those who die from HIV need active pain management during the last 3 months of their life, while 80% of those who die from cancer need pain medication. Yet, access to oral morphine is available in fewer than 11 African countries.[1]

Breast cancer in South Africa

The precise incidence of breast cancer in SA is unknown. There is no reliable national data registry, and the information available is gleaned from individual units in the larger healthcare centres. It is known that in state healthcare facilities, a significant number of patients present with clinically advanced disease. Treatment options are further compounded by a high incidence of HIV disease.

In a survey, the stage, HIV status and type of breast cancer in 1 200 women who presented to Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital were documented. Of those tested, 19.7% were HIV-positive, over half presented with locally advanced or metastatic cancer (stage 3 or 4) and 1.5% presented with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). In a screened UK population, nearly 20% of women were diagnosed with DCIS.[9,10]

The management guidelines formulated in HICs are unaffordable, unobtainable and inappropriate for the management of breast cancer in LICs. Sambo et al.[11]have summarised the challenges in cancer management in SSA as follows:

• Absence of cancer prevention, control policy, strategies and programmes. Most experts agree that mammographic screening is unaffordable and breast examination is generally not a good screening modality. However, studies have not tested this premise in countries where most tumours are clinically obvious or advanced at presentation. A Sudanese pilot study by Abuidris et al.[12] showed the potentially beneficial effects of a cancer awareness programme using trained nonmedical volunteers, and suggests that clinical breast examination may be useful in low-resource settings.[13] There is nonational breast cancer policy in place, and regional programmes are in their infancy. A greater emphasis needs to be placed on competent diagnostic units to fast track patients with breast cancer to the appropriate centre of care.

• Insufficient recent and comprehensive data for cancer and death registration. For any country to plan a comprehensive health policy, a national register of disease incidence must be kept.

• The heavy economic and psychosocial burden of cancer.

• Inadequate or no information about cancer, insufficient numbers of skilled research. A number of initiatives are aimed at retaining medical personnel in their country of origin. The Medical Education Partnership Initiative (MEPI) 2010 provides funds to foreign institutions in SSA countries that receive US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (US PEPFAR) support to develop or expand models of medical education. The aim is to improve the quality and quantity of graduates, retain specialists and improve research.[14] The African Organisation for Training and Research in Cancer (AORTIC) held a workshop in Durban to discuss ways of retaining specialists in their country of training.[15]

• The high cost of immunisation against human papillomavirus and other infections that cause cancer. In SA, the state has recently started a national human papillomavirus immunisation campaign.

• Unavailability of secondary prevention for cancer amenable to this intervention.

• Unaffordability of treatment resources and neglect of palliative care. Oral morphine must be made available for use in palliative care.

• Absence of collaboration or co-ordination of interventions with regard to stakeholders and donors to combat cancer. It is imperative that interested stakeholders unite and work towards a common goal.

Conclusion

The incidence of breast cancer will increase significantly in all LICs. SA and its neighbouring countries will be significantly affected. It is therefore imperative that healthcare resources, policies and planning focus on this in a co-ordinated and rational way.

References

1. O’Brien M, Mwangi-Powell F, Adewole I, et al. Improving access to analgesic drugs for patients with cancer in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:e176-182. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70343-1] [ Links ]

2. Lingwood RJ, Boyle P, Milburn A, et al. The challenges of cancer control in Africa. Nat Rev Cancer 2008;8:398-403. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrc2372] [ Links ]

3. National Cancer Institute. Cancer research funding. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/NCI/research-funding (accessed 30 June 2012). [ Links ]

4. National Cancer Institute. Cancer, Changing the Conversation: The Nation’s Investment in Cancer Research. An Annual Plan and Budget Proposal for Fiscal Year 2012. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2011. http://www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/breastscreen/publications/baso2010-2011.pdf (accessed 9 March 2014). [ Links ]

5. Anderson BO, Cazap E, El Saghir NS, et al. Optimisation of breast cancer control in low-resource and middleresource countries: Executive summary of the Breast Health Global Initiative Consensus, 2010. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:387-398. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70031-6]

6. World Bank. World development indicators 2012. http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/worlddevelopment-indicators/wdi-2012 (accessed 9 March 2014). [ Links ]

7. African Progress Panel. Maternal health: Investing in the lifeline of healthy societies and economies. African Progress Panel Policy Brief, September 2010. http://www.who.int/pmnch/topics/maternal/app_maternal_ health_english.pdf (accessed 9 March 2014). [ Links ]

8. Ozgediz D, Kijjambu S, Galukande M, et al. Africa’s neglected surgical workforce crisis. Lancet 2008;371:627-628. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60279-2] [ Links ]

9. Cubasch H, Joffe M, Hanisch R, et al. Breast cancer characteristics and HIV among 1,092 women in Soweto, South Africa. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013;140(1):177-186. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10549-013-2606-y] [ Links ]

10. McCormack VA, Joffe M, Van den Berg E, et al. Breast cancer receptor status and stage at diagnosis in over 1,200 consecutive public hospital patients in Soweto, South Africa: A case series. Breast Cancer Research 2013,15:R84. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/bcr3478] [ Links ]

11. Sambo LG, Dangou JM, Adebamowo C, et al. Cancer in Africa: A preventable public health crisis. J Afr Cancer 2012;4:127-136. [ Links ]

12. Abuidris DO, Elsheikh A, Ali M, et al. Breast-cancer screening with trained volunteers in a rural area of Sudan: A pilot study: Lancet Oncol 2013;14:363-370. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70583-1] [ Links ]

13. Panieri E. Breast-cancer awareness in low-income countries (Editorial). Lancet Oncol 2013;14:274-275. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70020-2] [ Links ]

14. Collins FS, Glass RE, Whitescarver J, et al. Developing health workforce capacity in Africa. Science 2010;330:1324-1325. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1199930] [ Links ]

15. Morhason-Bello IO, Odedina F, Rebbeck TR, et al. Cancer Control in Africa 1. Challenges and opportunities in cancer control in Africa: A perspective from the African Organisation for Research and Training in Cancer. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:e142-151. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70482-5] [ Links ]

Corresponding author:

Corresponding author:

J Edge

(jennyedgel234@me.com)