Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.104 n.4 Pretoria Apr. 2014

FORUM

CLINICAL PRACTICE

The risks of gastrointestinal injury due to ingested magnetic beads

S Cox, R Brown; A Millar; A Numanoglu; A Alexander; A Theron

The authors are based in the Department of Paediatric Surgery, Red Cross War Memorial Children's Hospital and University of Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Accidental ingestion of foreign bodies is a common problem in children. Magnetic bead toys are hazardous, having potentially lethal consequences if ingested. These magnets conglomerate in different segments of bowel, causing pressure necrosis, perforation and/or fistula formation anywhere along the gastrointestinal tract. A clinical diagnostic pitfall is that the appearance on the initial abdominal radiograph may be misinterpreted by the uninitiated as a single metallic object without any intervening intestinal wall. Symptoms do not occur until complications have developed, and even then, unless magnet ingestion is suspected, treatment may initially be mistakenly expectant, as with any other foreign body. After observing a case of multiple magnet ingestion that led to the rapid onset of small-bowel inter-loop fistulas and peritonitis, we attempted to reproduce the likely sequence of events in a laboratory setting using fresh, post-mortem porcine bowel as an animal model and placing magnetic toy beads within the bowel lumen. Pressure-induced perforation appeared extremely rapidly, replicating the operative findings in two of our cases. We propose that if magnet ingestion is suspected, early endoscopic or surgical retrieval is mandatory. Appropriate, rapid surgical intervention is indicated. Laparoscopy offers a minimally invasive therapeutic option.

Accidental ingestion of foreign bodies is a common problem in children. Ordinarily, most of these pass through the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) unnoticed. Since 1995, there have been an increasing number of reports on the consequences of toy magnet ingestion.[1] One ingested magnet should not cause any problems, but when multiple individual magnets are ingested, they can cause considerable morbidity.[2] This occurs when magnets conglomerate in different segments of bowel with forces of up to 1 300 G,[1] causing pressure necrosis, perforation and/or fistula formation anywhere along the GIT.[3] Other reported magnet-induced problems include ulceration,[4] gastric outlet or bowel obstruction,[5] oesophageal perforation,[6] gastro-enteric fistulas,[7] small-bowel volvulus,[8] and appendicitis due to ileocaecal fistulation.[9]

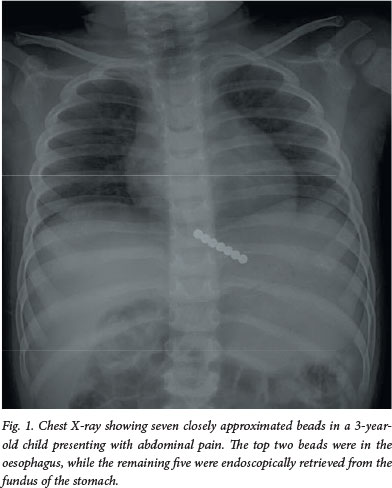

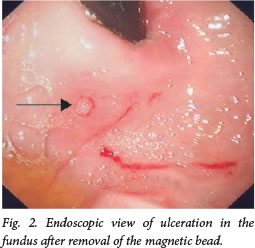

The serious consequences of multiple magnet ingestions have become apparent to the Department of Paediatric Surgery, Red Cross War Memorial Children's Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa, in the past year. We have recently published a case report of a 2-year-old girl who underwent surgery after presenting with a magnet-induced bowel perforation.[2] Subsequent to this report, we have operated on another two children. One patient was a 3-year-old boy, with seven retained magnets (Fig. 1). At endoscopic removal, two were found to be in the lower oesophagus and adherent to five in the gastric fundus. Perforation had not occurred, but ulceration was evident (Fig. 2). The latest patient is a 3-year-old child who presented with an acute abdomen and septic shock. At laparotomy, she was found to have free pus in the abdomen and two small perforations in her distal ileum, the result of magnet-induced pressure necrosis. She spent 2 days in intensive care postoperatively, but made a full recovery.

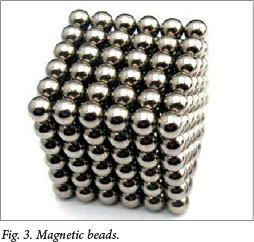

Numerous magnet toys have been implicated in this growing problem, with an estimated 1 700 ingestions treated in emergency departments in the USA between January 2009 and December 2011.[10] The magnets ingested by our patients have been spherical, powerful rare-earth magnets ~4 mm in diameter. They are freely available at many large retail stores and sold as an executive stress toy (Fig. 3.) The packaging indicates that they are not suitable for children and warns consumers to seek medical advice if ingested. Most are made of neodymium, iron and boron or other rare-earth metals and are extremely powerful magnets. The magnetic field typically produced by rare-earth magnets can be in excess of 1.4 teslas. There have been product recalls on certain magnetic toys in the USA because of these issues; however, we are unaware of any such action in South Africa to date.

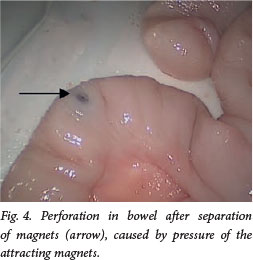

After the first case of multiple magnet ingestion led to the rapid onset of small-bowel inter-loop fistulas and peritonitis,[2] we attempted to reproduce the likely sequence of events in a laboratory setting.

We used a 60 cm segment of fresh, postmortem porcine bowel as an animal model. We placed magnetic toy beads within the bowel lumen at intervals along its length. The bowel was gently manipulated to simulate normal small-bowel movement in the peritoneum. We used the facilities in our Surgical Skills Training Centre including a laparoscopic training box, a 30-degree lens and Karl Storz high-definition stack and monitors to observe the sequence of events.

We introduced standard 5 mm instruments to assess our ability to intervene therapeutically in these cases.

There was immediate conglomeration of the magnets, that came within 2 cm of each other trapping intervening bowel wall. Pressure-induced perforation appeared extremely rapidly, within a few minutes (Fig. 4). This replicated the operative findings in two of our cases.

The magnets were strongly attracted to the tips of the laparoscopic instruments and enabled delivery of bowel for further surgical intervention (Fig. 5).

Most reported complications of multiple magnet ingestion are due to pressure necrosis-induced perforation or fistulation. The injury model described attests to the fact that the sequence of events occurs very rapidly.

In clinical practice, a high degree of suspicion is required to differentiate a swallowed magnet conglomerate or similar foreign body from two separate groups of magnets in different parts of the intestine that have attracted each other and are causing pressure necrosis. A clinical diagnostic pitfall is that the appearance on the initial abdominal radiograph may be misinterpreted by the uninitiated as a single metallic object without any intervening intestinal wall. Symptoms do not occur until complications have developed, and even then, unless magnet ingestion is suspected, treatment may initially be mistakenly expectant, as with any other foreign body.[11]

Appropriate, rapid surgical retrieval of these magnets is recommended. To make the connection between these seemingly innocuous foreign bodies and the potentially fatal consequences of their ingestion, we would like to introduce the problem to a wider medical audience than the readers of specialist paediatric surgical journals in which the problem has been increasingly presented.

We propose that if magnet ingestion is suspected, early endoscopic or surgical retrieval is mandatory. Laparoscopy is potentially very useful in locating the magnets, as they will adhere to the instrument tips. The magnet-containing bowel can then be exteriorised for magnet extraction and repair. Intra-operative radiological screening would confirm that all magnetic beads have been removed.

Conclusion

Magnetic bead toys are hazardous, having potentially lethal consequences if ingested. Appropriate, rapid surgical intervention is indicated. Laparoscopy offers a minimally invasive therapeutic option.

1. Honzumi M, Shigemori C, Ito H, et al. An intestinal fistula in a 3-year-old child caused by the ingestion of magnets: Report of a case. Surg Today 1995;25(6):552-553. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00311314] [ Links ]

2. Adikibi BT, Arnold M, van Niekerk G, Alexander A, Numanoglu A, Millar AJ. Magnet bead toy ingestion: Uses and disuses in children. Pediatr Surg Int 2013;29(7):741-744. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00383-013-3275-y] [ Links ]

3. Kabre R, Chin A, Rowell E, et al. Hazardous complications of multiple ingested magnets: Report of four cases. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2009;19(3):187-189. [http://dx.doi. org/10.1055/s-2008-1038824] [ Links ]

4. Cortés C, Silva C. [Accidental ingestion of magnets in children: Report of three cases]. Rev Med Chil 2006;134(10):1315-1319. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0034-98872006001000016] [ Links ]

5. Oestreich AE. Multiple magnet ingestion alert. Radiology 2004;233(2):615. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1148/radiol2332041446] [ Links ]

6. Seo TJ, Park CH, Jeong HK, et al. Endoscopic removal ofimpacted magnetic foreign bodies in the gastroesophageal junction. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2011;21(6):e313-e315. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/SLE.0b013e318231206f] [ Links ]

7. Brown JC, Murray KF, Javid PJ. Hidden attraction: A menacing meal of magnets and batteries. J Emerg Med 2012;43(2):266-269. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.09.003] [ Links ]

8. Nui A, Hirama T, Katsuramaki T, et al. An intestinal volvulus caused by multiple magnet ingestion: An unexpected risk in children. J Pediatr Surg 2005;40(9):e9-e11. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.05.065] [ Links ]

9. Robinson AJ, Bingham J, Thompson RL. Magnet induced perforated appendicitis and ileo-caecal fistula formation. Ulster Med J 2009;78(1):4-6. [ Links ]

10. Consumer Product Safety Commission. Safety standard for magnet sets. 16 CFR Part 1240. Fed Reg 7(171):53781-53801. [ Links ]

11. Van Schie K. Fake tongue ring lands girl in hospital. The Star. 30 August 2013. http://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/gauteng/fake-tongue-ring-lands-girl-in-hospital-1.1570452 (accessed 18 February 2014). [ Links ]

Corresponding author:

Corresponding author:

S Cox

(sharon.cox@uct.ac.za)

Accepted 25 September 2013.