Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.104 n.1 Pretoria Jan. 2014

CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION

ARTICLE

Psychiatry in primary care using the three-stage assessment

C A DraperI; P SmithII

IMB ChB, FCFP (SA) School of Public Health and Family Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

IIMB ChB, FCPsych (SA) Lentegeur Hospital and Department of Psychiatry, University of Cape Town, South Africa

The burden imposed by mental illness on local services is immense and cannot be borne exclusively by psychiatrists based in specialist clinics and institutions. To address the massive demands for health services in the country the National Department of Health has adopted a strategy that prioritises a model of integrated district-based primary care. Among the many challenges that have to be confronted when efforts are made to integrate psychiatry into primary care, and one that this paper seeks to address, is the need to develop a model of assessment and treatment that is accessible, yet effective, and responsive to the particular needs of psychiatric patients who access these services.

Integrating traditional psychiatric history and examination with the three-stage assessment

Traditionally, psychiatry is taught to medical students by psychiatrists working in psychiatric institutions. Therefore, the experience gained usually relates to severe mental illness in hospitalised patients. In a primary care setting, patients may be seen in the early, undifferentiated stages of mental illness. The new graduate often has to 'back translate' the knowledge gained at medical school to diagnose and manage mental illness at a time when the illness is still in the process of establishing itself, as the florid, classic presentations seen in psychiatric hospitals are seldom seen at a primary care level. The approach generally taught is therefore ill-suited to a primary care environment and is rendered doubly problematic owing to time and service pressures imposed on these services, early state of presentation, often brief and fragmentary nature of the clinician-patient encounters, as well as the need to consider all of the other health problems that may be affecting the patient at the time. While the clinical presentations may be less dramatic, it would be a mistake to assume that assessing a patient with possible mental illness in a primary care setting is less complex than in specialist clinics. On the contrary, assessments may be even more complex owing to undifferentiated clinical and social problems, comorbid conditions, and the usual service constraints within the facility. Furthermore, failure to understand the individual and their context often leads to an inadequate or incorrect diagnosis. Therefore, it is clear that a truly holistic, integrated, person-based approach is needed in the primary care setting, but one that can be adapted to meet the particular challenges that define this level of health service.

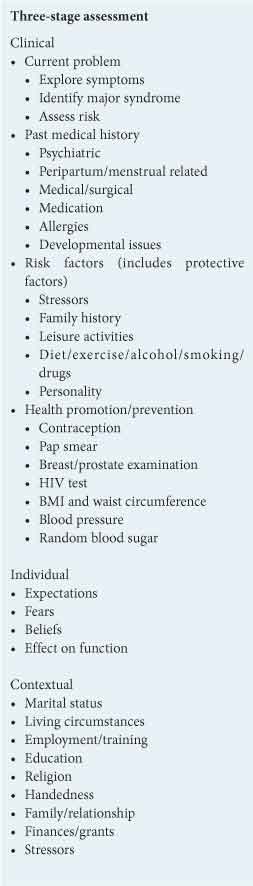

The model taught in family medicine is the three-stage assessment, consisting of a clinical, individual and contextual assessment, and is based on the principles of family medicine.[1,2] This is derived from an understanding of the general systems theory and the systems hierarchy as well as taking into account the evidence in favour of patient-centred and family-orientated care.[2] On reflection, this can be seen to dovetail well with many aspects of the traditional psychiatric clerk and biopsychosocial approach. However, it has the added benefit of including screening for other health problems as part of the initial assessment. While the three-stage assessment can appear extensive and therefore time-consuming to conduct comprehensively, all the information does not need to be collected at the initial consultation. The most important details under each stage can be elicited initially, with information added and issues explored in more depth at each follow-up consultation.

Clinical assessment

The first element of the three-stage assessment is the clinical (or biomedical) assessment, which includes exploring the current problem, past medical history and relevant risk and protective factors, and then addressing health promotion and prevention using opportunistic screening.

In exploring the patient's presenting complaint or primary source of difficulty, it would be useful to try to place these within a diagnostic group or category. The paper by Parker[3] elsewhere in this issue, which proposes a syndromic approach to assessment, is particularly helpful. It facilitates an appropriately focused line of further questioning and investigation. Patients should also be risk-assessed to define the degree to which they are a danger to themselves or others. The level of risk must be identified and recorded and appropriate steps taken to minimise it.

Next, is important to establish the patient's past medical history, including past psychiatric history (menstrual and perinatal mental health if relevant), past medical and surgical histories, previous medication use and allergies, as well as relevant developmental history and childhood stressors. This need not be done comprehensively at the initial consultation but could be elicited further at follow-up appointments.

Risk factors for mental illness (as well as protective factors) should be explored. These would relate to significant life stressors, a family history of mental illness or substance use, details about leisure activities, personal substance use (including alcohol, smoking and illicit substances), diet and exercise habits and finally a brief personality query (to establish the habitual ways in which the patient thinks of him/herself and others and copes with stress, e.g. 'What kind of a person would you say you are? How do others see you?'). Ideally, one should stage each risk factor in terms of the patient's readiness to change his/her behaviour and then use an agenda-setting technique to decide which risk factor to address with motivational interviewing to support behaviour change.

The final component of the clinical assessment is to provide health promotion and disease prevention for the patient. Depending on the age, gender and individual risk factors, this could include: contraceptive advice and prescription, a Pap smear, a breast or prostate examination, an HIV test, measurement of waist circumference and body mass index (BMI) and/or a check of the patient's blood pressure and blood glucose.

Individual assessment

The second element of the three-stage assessment is the individual assessment. This focuses on the patient's experience and understanding of his/her illness. To meet the patient's agenda for the consultation, it is important to ask directly about their expectations of what will be addressed, any worries or fears relating to the presentation, beliefs about what is causing the current problem and how this problem is affecting their ability to function within the community. It may be helpful to open the consultation with questions such as: 'What were you hoping I could do for you today?', 'What was the worst thing that you thought this problem could be?', 'Is there anything else worrying you?' or 'What do you think might be causing this problem?'. This approach ensures that the consultation begins with open-ended questions, to direct and focus the rest of the interview, followed by closed-ended questions, to ensure that the most important aspects for both clinician and patient are addressed.

Contextual assessment

Finally, a contextual assessment should be made. The aim of this aspect of the three-stage assessment is to establish how the patient's family and community interact and how this affects his/her illness. Important factors to enquire about would be the patient's marital status and family members (including any supportive or difficult relationships), the physical home environment and the community in which he/she lives (including the prevalence and effect of trauma, violence and poverty on his/her daily life), highest level of education (HLOE) and any additional training, current (and previous) employment, handedness, religious affiliation, financial difficulties and eligibility for social grants. Finally, it is important to establish any other relevant stressors that were not previously mentioned, which could relate to a recent major change or loss, isolation, conflict or maladjustment. A genogram and ecomap can be useful tools to capture contextual history graphically and can be amended fairly easily during future consultations as more details emerge.

Physical examination

Based on the history elicited, it important to proceed to a focused physical examination. First, conduct a general examination, taking note specifically of the patient's vital signs, general physical appearance (including signs of nutrient deficiencies), signs of drug or alcohol abuse or withdrawal, signs of previous trauma or surgery (especially to the head and neck) and features of medication side-effects (such as coarse tremor or Parkinsonism). A systemic screen should then be performed to rule out any other illnesses, concluding with a focused neurological examination relevant to the patient's presenting complaint. From the observation and discussion that occurs throughout the consultation, a summary of the patient's mental state (MSE) should be noted.

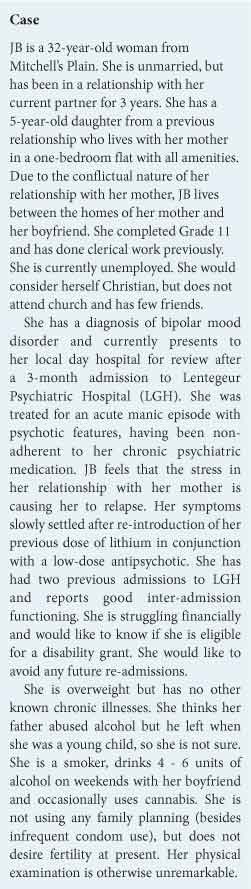

As is evident from the three-stage assessment (Table 1), the interaction between this patient, her family and her environment and her mental illness is far more complex than simply confirming her diagnosis and re-prescribing her medication. Without a comprehensive assessment, many of the factors that contribute to this patient accepting and coping with her illness may be missed. Risk factors that could further compromise her health may not be addressed, and support systems and patient-generated solutions not accessed. While the assessment could appear to be laborious and overly extensive, it is important to emphasise that patients with mental illness generally require a long-term relationship with their primary care physician, with several follow-up appointments to monitor progress. With the passage of time and good continuity of care, different aspects of the assessment can be prioritised on different occasions and explored in more detail as time allows to ensure that, over time, a comprehensive assessment and management strategy are put in place.

The use of the three-stage assessment emphasises a number of key principles of family medicine, namely that the clinician: be committed to the person rather than the disease process; seeks to understand the context of the illness; sees every consultation as an opportunity for health promotion; and sees the importance of the subjective aspects of medicine.[4] These principles tie in with both the biopsychosocial approach emphasised in psychiatry as well as newer developments in psychiatric practice, such as the utilisation of a recovery model. This highlights the need to have a more positive outlook on recovery goals in mental illness, emphasising person-centredness and community re-integration, which are dependent on strengthening primary care and community-based services. Chronic, non-communicable diseases comprise a significant portion of the workload at a primary care level, and in many ways mental illness should be viewed as another chronic disease. Current chronic disease policies[5] emphasising facility-based stabilisation with community-based maintenance could be extended to include mental health users, encompassing the use of community health workers, adherence counsellors and other lay community-based health workers to support these patients and provide a cost-effective means to reduce facility workload.

When using the three-stage assessment to evaluate a mental health user at a primary care level, one must remember that the model suggested is merely a guide that should be used in a way that is flexible and adaptable to the unique needs of each patient. This helps to ensure that each patient encounter is appropriately therapeutic, with a particular emphasis on patient centredness and autonomy. It is hoped that even in an environment of overwhelming demand and scarce resources to meet the needs of large patient numbers, the three-stage assessment model outlined here could prove to be a helpful and effective tool for primary care practitioners.

In conclusion, in view of the burden of mental illness that is borne in our services, and the important role that primary care clinicians have to play, psychiatric patients must be assessed and followed up at a primary care level in a holistic, person-centred, effective and efficient manner. The three-stage assessment provides a comprehensive model that can be easily adapted to suit the needs of a patient presenting with a mental illness, while simultaneously assessing and screening for other health issues and factors that are likely to have a direct or indirect effect on overall patient wellness.

Summary

- Mental illness imposes a massive burden on all levels of service, including primary care.

- Challenges particular to primary care include the overwhelming service loads and time/resource constraints.

- A further challenge revolves around the frequent mismatch between undergraduate teaching and the clinical nature of psychiatric care in primary level clinics.

- Clinical presentations at primary level are often nonspecific and undifferentiated, and complicated by comorbid medical illness and psychosocial stressors.

- The three-stage assessment that embraces the core principles of family practice can be adapted to incorporate the psychiatric needs of patients in primary care and deliver a truly holistic and integrated assessment of their individual needs.

- These adaptations need not involve additional training or the need for additional clinical tasks.

- Psychiatric management requires continuity of care within an enduring therapeutic relationship, which provides the ideal framework within which a comprehensive assessment and management plan can be formulated.

- Successful adaptations to the three-stage assessment could provide an effective (and efficient) model for the integration of psychiatry at the primary care level.

References

1. Fehrsen GS, Henbest RJ. In search of excellence. Expanding the patient-centered clinical method: A three stage assessment. Family Practice 1993;10:49-54. [ Links ]

2. Mash B, ed. Handbook of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. Cape Town: Oxford University Press, 2011. [ Links ]

3. Parker J. Adapting the psychiatric assessment for primary care. S Afr Med J 2014;104(1):75. [http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.7731] [ Links ]

4. McWhinney IR, Freeman T. Textbook of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. [ Links ]

5. Provincial Government of the Western Cape, Department of Health. Adult Chronic Disease Management Policy: A Strategy for the Five Key Conditions. Cape Town: Western Cape Department of Health, 2009. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

C Draper

(cpurdue@gmail.com)