Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.104 n.1 Pretoria Jan. 2014

RESEARCH

Parents' perceptions of HIV counselling and testing in schools: Ethical, legal and social implications

R GwandureI; E RossII; A DhaiIII; J GardnerIV

IDip Educ, Adv Cert Educ, BEd Hons (Inclusive Education), MSc Med (Bioethics & Health Law). Steve Biko Centre for Bioethics, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIBA (Social Work), MA (Social Work), PhD. Steve Biko Centre for Bioethics, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIIMB ChB, FCOG, LLM, PG Dip Int Research Ethics. Steve Biko Centre for Bioethics, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IVBA (Law & Industrial Sociology), LLB, MSc Med (Bioethics & Health Law). Steve Biko Centre for Bioethics, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

In view of the high prevalence of HIV and AIDS in South Africa, particularly among adolescents, the Departments of Health and Education have proposed a school-based HIV counselling and testing (HCT) campaign to reduce HIV infections and sexual risk behaviour. Through the use of semi-structured interviews, our qualitative study explored perceptions of parents regarding the ethico-legal and social implications of the proposed campaign. Despite some concerns, parents were generally in favour of the HCT campaign. However, they were not aware of their parental limitations in terms of the Children's Act. Their views suggest that the HCT campaign has the potential to make a positive contribution to the fight against HIV and AIDS, but needs to be well planned. To ensure the campaign's success, there is a need to enhance awareness of the programme. All stakeholders, including parents, need to engage in the programme as equal partners.

South Africa (SA) has 5.6 million people estimated to be living with HIV and AIDS.[1]With a prevalence rate of 10.9%, the country is experiencing particular challenges relating to high HIV infection rates among youth aged 15 - 24 years.[2-4] Sexual debuts are reported to occur before the age of 12 years in both girls and boys.[4]

The SA Department of Health has planned an extensive HIV counselling and testing (HCT) campaign, which forms part of the 'basket of services' offered by the new Integrated School Health Programme.[5] Every learner in secondary school who is over 12 years of age will be offered the option of taking an HIV test. This meets the legal requirement for consent for HCT according to the Children's Act,[6] which acknowledges that consent for an HIV test on a child may be given by the child, if the child is 12 years of age or older; or, if under the age of 12 years, is of sufficient maturity to understand the benefits, risks and social implications of such a test. However, parents may not be aware of their parental limitations in terms of children's health rights. Since HCT is going to be performed in schools, children need reassurance that their information will be kept confidential by the implementers of the campaign. This is important, in that lack of trust on the part of children could result in low participation rates. Although the HCT campaign is well intentioned, if implemented by people without proper training and qualifications in managing the emotional well-being of adolescents, the programme could have a damaging effect on parents' and children's psychosocial well-being.[7]

The main aim of this study was therefore to ascertain how a group of parents of children in high school perceive rollout of the HCT campaign in high schools in terms of ethical, legal and social issues.

Methods

The study adopted an exploratory-descriptive research strategy located within an interpretive qualitative paradigm and was conducted using semi-structured interviews. Objectives were to explore parents' views about the HCT campaign to be conducted in high schools, to determine whether parents would be in a position to engage with their children on the HCT campaign, to elicit information on parents' awareness of the Children's Act with regard to HIV testing, and to ascertain parents' views about knowing their children's HIV test results and how they thought they would react to the results.

The study population comprised parents with children attending high schools. The sample was purposively selected and Katlehong, Gauteng Province, was chosen as the research site because the population of this area closely represents the majority of the SA population. Snowballing sampling was used until data saturation was reached, namely after interviews with 20 parents. It is acknowledged that the small, non-probability sample precluded generalisation or transferability of the findings to the broader population of parents of high-school children in SA.

A pre-test using 5 parents was conducted to assess suitability of the interview schedule. Qualitative data from the interviews were analysed using thematic content analysis. Approval for the study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

Results

Profile of participants

There were 20 participants: 13 mothers and 7 fathers, average age was 40 years (range 28 - 53 years), and their children's ages ranged from 12 to 18 years. Participants belonged to one ethnic group (black), as they were all recruited from a township in Gauteng Province.

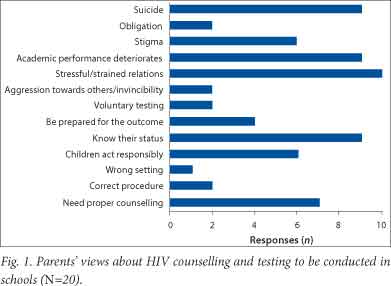

Parental views on HCT to be conducted in schools

While 19 parents were in favour of HCT, they also articulated concerns regarding the campaign (Fig. 1). Eleven supported the campaign because it would help children know their status and enable them to act responsibly. Examples of responses encapsulating this theme included: '... in order to know how to behave', '...for her own benefit', '...I know my child is safe ...'. Six parents, although supportive of the campaign, were afraid to know their children's HIV status because they anticipated that it would be stressful and would strain their relationships with their children. Five parents expressed concern that children's performance at school would be negatively affected and that some children might refuse to return to school. Four, also in favour of the campaign, stated that they would need to be prepared for the test results by the counsellors responsible for implementing the campaign, and would want to be consulted by their children before consenting to the children's participation.

Nine parents worried that informing children of their HIV positivity would cause them to commit suicide because it would be difficult for them to cope with news of that nature, while 7 stated that there was a need for proper counselling in order to prevent suicide. Six parents were concerned that their children would be stigmatised at school.

Four parents expressed concern about maintenance of confidentiality and privacy; 2 stressed that the correct procedures would have to be followed before implementing the programme, and 2 emphasised that they would support their children's participation in HCT if the children were able to make their own choices without being coerced or unduly influenced. One parent was concerned about the outcome of HCT, namely that children found to be positive might demonstrate '... aggression towards parents and even teachers' and that they might not change their sexual behaviour but would instead continue to endanger themselves and others. Two parents emphasised that supporting their children if they were found to be HIV-positive was an obligation and not a choice. Lastly, 1 parent argued that school was the wrong setting for HCT, because it is a place of learning and not a healthcare centre.

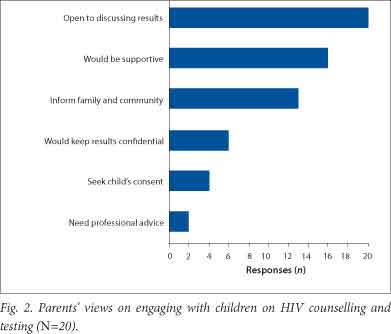

Engaging with children on the HCT campaign

All the parents were interested in discussing their children's results and would maintain supportive parent-child relations irrespective of the outcome (Fig. 2). While 13 parents anticipated that they would not keep the results to themselves but would tell a friend, family member, church or support group in their community, 6 parents emphasised that they would keep the results confidential for fear of being judged. While 4 parents believed that it was the child's choice whether or not to disclose his/her HIV status, others assumed that they (the parents) were responsible for decisions about disclosure of the HIV status of their children to family and friends. Two parents said that they would seek professional advice.

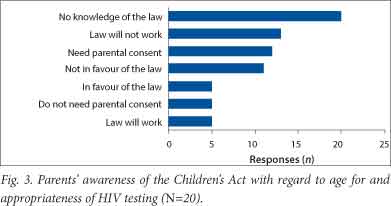

Awareness of the Children's Act

No parent was aware of the Children's Act No. 38 of 2005 (Fig. 3).[6] When informed about the sections pertinent to HCT, 11 parents indicated that they disapproved of them. Thirteen were of the opinion that the law would not work because it afforded too much freedom to young children. Twelve parents felt that children needed parental consent to take an HIV test, because the results were potentially traumatising and might cause children to commit suicide. Eleven parents were not in favour of the law, believing that 12-year-olds were too young to be given freedom to engage in sexual activity. While 5 parents were supportive of the law ('... it is a good law because now even children in primary school get a baby ... It is totally acceptable, it is for the children's own benefit ...'), they believed that it would only work if parents were part of the legal process.

Parents' views about knowing their children's HIV results and their anticipated reactions

Seventeen parents expressed the wish to retain supportive parent-child relations, 7 anticipated that they would be disappointed and angry if their children tested HIV-positive but that they would find a way to offer moral support, and 2 felt that they would require counselling before they were made aware of the results (Fig. 4). An obvious limitation to these reactions is that they were based on the hypothetical possibility of a positive result. It is also possible that some participants might have given socially desirable responses but would react differently when confronted with the real-life situation of a child being declared HIV-positive.

Discussion, conclusions and recommendations

Parents' views on the proposed HCT campaign show that targeting high-school learners for HIV testing could potentially be very successful, with positive effects in the fight against HIV and AIDS in SA. Parents anticipated that the introduction of HCT in schools could encourage children of all ages who are sexually active to be tested, thereby reducing the prevalence of the disease. If the HCT campaign was implemented successfully, the stigma attached to HIV was likely to be reduced.

However, parents also feared that HIV testing in high schools might have repercussions if the programme was not well planned and if parents did not play an integral role in it. They reported that they had received little or no information concerning the HCT campaign, and they felt that their role as parents, in terms of supporting a child who tested positive for HIV, was not considered or respected. They generally felt that they had an important role to play both during and after the campaign.

These findings indicate that the parents who participated were not against the campaign, but would need preparation on how to deal with children infected and affected by HIV. The parents' call for appropriate counselling appeared to stem from a desire to protect their children from social and psychological harms. It is therefore recommended that the Departments of Health and Education ensure that they are in a position to offer counselling to parents. In addition, pre-test counselling by qualified healthcare professionals should be provided in order to afford learners the opportunity to ask questions and make informed decisions.

The success of the HCT campaign is based on potential support from all stakeholders, including parents, educators and healthcare workers. However, we noted that parents were not aware of the Children's Act No. 38 of 2005.[6] The implementers of the HCT programme therefore need to create awareness of this Act among parents and teachers, including information on children's rights. There is also a need for qualified professionals to monitor the implementation of HCT and evaluate how effectively it adheres to ethical principles.

It must not be forgotten that the HCT campaign has the potential to contribute towards stigmatisation, discrimination against and isolation of children and families living with HIV and AIDS. Parents and learners need to be prepared to cope with discrimination in the event that their children or siblings test positive for HIV. Attention to all these risk factors could ensure that the potential benefits of the HCT programme outweigh the risks.

References

1. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Update on the Global AIDS Epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS, 2012. [ Links ]

2. Chapman R, White RG, Shafer LA, et al. Do behavioural differences help to explain variations in HIV prevalence in adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa? Tropical Medicine and International Health 2010;15(5):554-566. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02483.x] [ Links ]

3. South African National AIDS Council. The National HIV Counselling and Testing Campaign Strategy, 2010. http://www.sanac.org.za (accessed 21 June 2011). [ Links ]

4. Shisana O, Rehle O, Simbayi LC, et al., and SABSSM team III. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence, Behaviour and Communication Survey 2008: A Turning Tide among Teenagers? Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2009. [ Links ]

5. Govender P. HIV testing in schools on cards. Sunday Times 2012; 30 September, p. 7. [ Links ]

6. Children's Act 38 of 2005. Government Gazette No. 28944, 19 June 2006. Pretoria: Government Printer, 2005. [ Links ]

7. Peltzer K, Tabane C, Matseke G, Simbayi L. Lay counsellor-based risk reduction intervention with HIV positive diagnosed patients at public HIV counselling and testing sites in Mupumalanga, South Africa. Evaluation and Programme Planning, 2010;33(4):379-385. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2010.03.002] [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

E Ross

(eleanor.ross@wits.ac.za)

Accepted 28 February 2013