Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.103 n.11 Pretoria Jan. 2013

RESEARCH

The prevalence of smoking and the knowledge of smoking hazards and smoking cessation strategies among HIV-positive patients in Johannesburg, South Africa

P WaweruI; R AndersonII; H SteelII; W D F VenterIII; D MurdochIV; C FeldmanV

IAga Khan University Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya

IISouth African Medical Research Council Unit for Inflammation and Immunity, Department of Immunology, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa

IIIWits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute and Department of Internal Medicine, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IVDivision of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA

VDivision of Pulmonology, Department of Internal Medicine, Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital and Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: While the detrimental effects of smoking among HIV-positive patients have been well documented, there is a paucity of data regarding cigarette smoking prevalence among these patients in South Africa (SA).

OBJECTIVES: To establish the frequency, demographics, knowledge of harmful effects, and knowledge of smoking cessation strategies among HIV-positive patients in Johannesburg, SA.

METHODS: We conducted a prospective cross-sectional survey using a structured questionnaire to interview HIV-positive patients attending the HIV Clinic at the Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital between 1 July and 31 October 2011.

RESULTS: Of 207 HIV-positive patients attending an antiretroviral therapy (ART) roll-out clinic, 31 (15%) were current smokers (23.2% of males and 7.4% of females) and a further 45 (21.7%) were ex-smokers. Most of the current smokers (30/31 patients) indicated their wish to quit smoking, and among the group as a whole, most patients were aware of the general (82.1%) and HIV-related (77.8%) risks of smoking and of methods for quitting smoking. Despite this, however, most (62.3%) were not aware of who they could approach for assistance and advice.

CONCLUSIONS: Given the relatively high prevalence of current and ex-smokers among HIV-positive patients, there is a need for the introduction of smoking-cessation strategies and assistance at ART roll-out clinics in SA.

The success of anti-smoking policies implemented in many developed countries has to a large extent been countered by the efforts of a highly resilient tobacco industry to target developing countries, many of which have less stringent anti-smoking strategies. Indeed, developing countries are now estimated to account for >70% of global tobacco consumption.[1,2] The increase in the frequency of smoking has coincided with the HIV/ AIDS pandemic in developing countries, presenting an ominous, interactive threat to public health. This is based on a number of studies, mainly from the USA and Europe, reporting that HIV-infected persons have extremely high rates of cigarette smoking,[3,4] associated, in turn, with a higher than expected increase in the frequency of co-morbidities, including cardiovascular diseases, bacterial pneumonia and cancers, as well as increased mortality. [3-6] Despite unrestricted access to advanced care and therapy, HIV-positive smokers appear to lose more life years from smoking than from HIV infection.[5] Moreover, smoking not only impacts negatively on the efficacy of antiretroviral therapy (ART),[7] but is also associated with treatment failure in tuberculosis (TB).[8]

Although the frequency of cigarette smoking in the general population in South Africa (SA), home to the largest number of HIV-positive people in the world, is estimated to be 16%,[9] the frequency in HIV-positive persons is uncertain. In a small pre-ART study conducted in a group (N=41) of predominantly male (n=34) subjects with pulmonary TB, the frequencies of cigarette smoking, measured according to urine cotinine concentrations, in the entire group, as well as in a subgroup of HIV-seropositive patients (n=10) were reported to be 63% and 70%, respectively, with cotinine concentrations rising significantly after 6 months of therapy.[10] These figures are comparable with a more recent study in a larger number of SA patients with active or latent TB in which the reported frequencies of cigarette smoking for the entire group (N=424) and the HIV-positive subgroup (n=119) were 68% and 71%, respectively.[11]

Given the relative paucity of data on this priority public health issue,[12] the current study was undertaken to establish the frequency and demographics of cigarette smoking and other types of substance abuse among HIV-positive patients attending the HIV Clinic at Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital (CMJAH), Johannesburg, SA.

Methods

This was a prospective cross-sectional survey of HIV-positive patients attending the HIV Clinic at CMJAH between 1 July and 31 October 2011. The hospital is a tertiary academic institution, which has an HIV clinic providing ART. All patients who entered into the study gave signed informed consent for participation. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Witwatersrand.

All patients were interviewed using a structured questionnaire that recorded demographic and clinical details and a detailed history of smoking status. Patients were also questioned about their knowledge of the overall harmful effects of smoking, as well as the effects of smoking on HIV infection, their knowledge of smoking-cessation strategies and previous attempts to quit. In 147 patients, a urine sample was tested for cotinine levels (ng/ml) using a solid-phase competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Calbiotech Inc., USA). A value >25 ng/ml was considered to be indicative of active smoking.

Data were entered into data sheets. Basic frequency analyses were used to describe the mean values and ranges on continuous variables, whereas proportions were used in the case of non-continuous variables.

Results

A total of 207 patients were entered into the database, of whom 108 (52.2%) were female. The majority (94.2%) of patients were black (white patients and coloured patients both 2.9%) reflecting the demographics of the clinic. The mean age of the patients was 39.9 years (range 19 - 62).

Overall, 31/207 (15%) were self-described current smokers, of whom 23/99 were male (23.2%) and 8/108 were female (7.4%). The average age of onset of smoking was 20 years (range 9 - 46). The average number of cigarettes smoked per day was 9 (range 1 - 30 cigarettes/day). There were 45/207 (21.7%) patients who were ex-smokers and 131/207 (63.3%) who had never smoked. Two patients were current smokers of cannabis in addition to cigarettes. Six patients also currently used snuff.

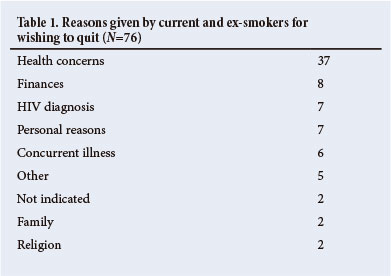

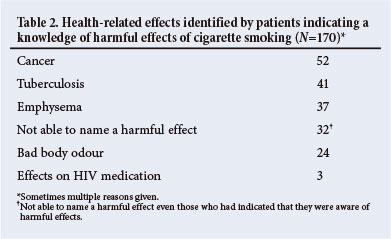

Most (30/31; 96.7%) smokers indicated that they wished to stop smoking for reasons shown in Table 1 (mainly expressing concern regarding health issues, but including HIV-positive diagnosis, concurrent illness, costs and also personal, family and religious concerns). A majority of the total patient population (170/207; 82.1%) indicated that they knew about the potential harmful effects of cigarette smoking in general, although several participants could not name a specific health hazard (Table 2). The majority (161/207; 77.8%) had knowledge of the potential harmful effects of cigarette smoking, specifically in relation to HIV infection; 34/207 (16.4%) believed there were no harmful effects of smoking on HIV infection and 12/207 (5.8%) were unsure.

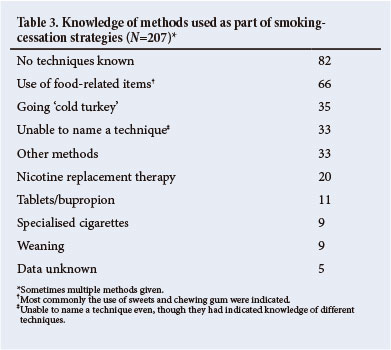

Quitting had been attempted by 64/76 (84.2%) current and ex-smokers. A majority (58%) indicated an awareness of methods for quitting smoking. Most patients (62.3%) were unaware of the resources available for advice and assistance.

As shown in Table 3, 82 patients were unaware of smoking-cessation agents/adjuncts, 66 patients indicated that various food substances and drinks were of value, 35 patients had knowledge of going 'cold turkey'; 33 patients were unable to name quitting techniques and 33 had knowledge of psychotherapy, avoiding smokers and drinkers, keeping busy, exercise, religion and prayer, rehabilitation and hypnotherapy. Twenty patients described various forms of nicotine replacement therapy (patches, gum and sprays), 11 patients described various drugs, such as bupropion, 9 patients described weaning from smoking and 9 patients described various forms of cigarettes (electronic, nicotine-containing or nicotine-free cigarettes). No data were recorded in 5 patients.

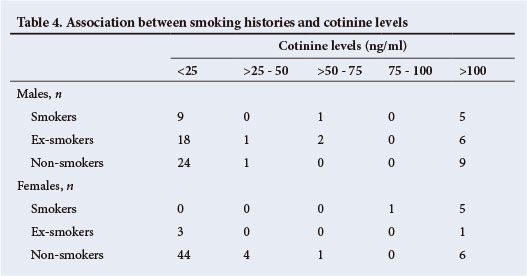

Urine specimens were obtained from 141 patients (21 current smokers, 31 ex-smokers and 89 non-smokers, Table 4) permitting measurement of cotinine levels. Cotinine levels were raised (>25 ng/ ml) in 43/141 patients (30.5% - 21 non-smokers, 10 ex-smokers and 12 current smokers). Nine patients who were smokers did not have raised cotinine levels. All female smokers had raised cotinine levels as did 6 of the male smokers (with an additional 9 male smokers who had cotinine levels that were not in the positive range).

Discussion

The main findings of this study of 207 HIV-infected patients attending an ART roll-out clinic were that 15% were current smokers and that the majority had indicated their wish to quit smoking. Furthermore, most were aware of the general (82.1%) and HIV-related (77.8%) risks of smoking, and of methods for quitting smoking, but 62.3% were not aware of the resources available for assistance and advice.

The overall prevalence of current smoking in the present study, based on the patient history, was 15%. This is similar to the frequency of smoking previously estimated in the general population in SA,[9] but much lower than that found in previous studies of HIV-infected SA people.[9-11] Factors that may have contributed include the fact that this study sampled a predominantly black SA population known to smoke less than any of the other population groups in the country, and there was a greater proportion of females (black females being much less likely to smoke).[9]

The true frequency of smoking may have been underestimated, since it was based on patient history alone, whereas the urine cotinine levels were actually raised in 43/141 patients (30.5%). The discrepancy was 28.4% (40/141 patients) between positive reported smoking history and elevated urine cotinine level (Table 4). In 19 males who indicated that they were either ex-smokers or non-smokers, the cotinine levels were raised (Table 4). The exact reasons for these discrepancies are uncertain, and while a discrepant history alone may be the major reason, it is possible that the relatively low numbers of cigarettes smoked or even intermittent smoking might offer an explanation. Passive exposure to cigarette smoke could have played a role, but possible passive smoking was not recorded.

Interestingly, in 9 males who indicated they were current smokers the urine cotinine levels were not raised (Table 4). Cotinine is the major metabolite of nicotine. It has a comparatively long half-life of about 17 hours in body fluid and is widely accepted as a sensitive and reliable marker of exposure to cigarette smoke and is considered to be more reliable than smoking history in determining smoking status.[11,12] One study[13] indicated a relatively poor correlation between patient history and the urine cotinine levels, especially in ex-smokers in whom smoking history can be misleading.

Encouragingly, most of the study population had insight into the general health and HIV-associated risks of smoking and almost all the ever-smokers indicated their willingness to quit smoking. That most of the study population lacked knowledge of resources offering assistance and advice, suggests the possibility for a public health intervention.

Cigarette smoking impacts on mortality, quality of life and co-morbid illnesses in HIV-infected patients,[3] even subsequent to the introduction of highly active ART.[4] There are serious medical conditions associated with cigarette smoking, including cardiovascular disease, pulmonary diseases and cancers,[14] with further good evidence that these risks decrease on smoking cessation. Although the prevalence of smoking in the current study is substantially lower than that reported in developed countries, the overwhelming infectious disease burden in the developing world potentially compounds its adverse effects. It is incumbent on all healthcare workers to encourage their HIV-infected patients to quit smoking.[4,15]

Acknowledgements. The authors thank the staff in the HIV Clinic and the patients for assistance with this study. D W F Venter is supported by the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). D Murdoch is part of the Fogarty International Center (grant no. K01TW008005). The content of the work is solely the responsibility of the authors and may not represent official views of the Fogarty International Center or the National Institute of Health. C Feldman is supported by the National Research Foundation (SA).

References

1. Giovino GA, Mirza SA, Samet JM, et al. Tobacco use in 3 billion individuals from 16 countries: An analysis of nationally representative cross-sectional household surveys. Lancet 2012;380(9842):668-679. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61085-X] [ Links ]

2. Eriksen M, MacKay J, Ross H. The Tobacco World Atlas, 4th ed. World Lung Foundation and American Cancer Society, 2012. http://www.tobaccoatlas.org (accessed 1 October 2013). [ Links ]

3. Crothers K, Griffith T, McGinnis KA, et al The impact of cigarette smoking on mortality, quality of life, and comorbid illness among HIV-positive veterans. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20(12):1142-1145. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0255.x] [ Links ]

4. Lifson AR, Lando HA. Smoking and HIV: Prevalence, health risks, and cessation strategies. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2012;9(3):223-230. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11904-012-0121-0] [ Links ]

5. Helleberg M, Afzal S, Kronborg G, et al. Mortality attributable to smoking among HIV-1 infected individuals: A nationwide, population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2013;56(5):727-734. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/cid/cis933] [ Links ]

6. De P, Farley A, Lindson N, Aveyard P. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Influence of smoking cessation on incidence of pneumonia in HIV. BMC Med 2013;11(1):15. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-15] [ Links ]

7. Shuter J, Bernstein L. Cigarette smoking is an independent predictor of nonadherence in HIV-infected individuals receiving antiretroviral therapy. Nicotine Tob Res 2008;10(4):731-736. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14622200801908190] [ Links ]

8. Tachfouti N, Nejjari C, Benjelloun MC, et al. Association between smoking status, other factors and tuberculosis treatment failure in Morocco. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011;15(6):838-843. [http://dx.doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.10.0437] [ Links ]

9. Peer N, Bradshaw D, Laubscher R, Steyn K. Trends in adult tobacco use from two South African demographic and health surveys conducted in 1998 and 2003. S Afr Med J 2009;99(10):744-749. [ Links ]

10. Plit ML, Theron AJ, Fickl H, van Rensburg CEJ, Pendel S, Anderson R. Influence of antimicrobial chemotherapy and smoking status on the plasma concentrations of vitamin C, vitamin E, β-carotene, acute phase reactants, iron and lipid peroxides in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 1998;2(7):590-596. [ Links ]

11. Brunet L, Pai M, Davids V, et al. High prevalence of smoking among patients with suspected tuberculosis in South Africa. Eur Respir J 2011; 38(1):139-146. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00137710] [ Links ]

12. Jarvis MJ, Tunstall-Pedoe H, Feyerabend C, Vesey C, Saloojee Y. Comparison of tests used to distinguish smokers from nonsmokers. Am J Public Health 1987;77(11):1435-1438. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.77.11.1435] [ Links ]

13. Bodmer CW, MacFarlane JA, Flavell HJ, Wallymahmed M, Calverley PM. How accurate is the smoking history in newly diagnosed diabetic patients? Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1990;10(3):215-220. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0168-8227(90)90064-Z] [ Links ]

14. Rahmanian S, Wewers ME, Koletar S, Reynolds N, Ferketich A, Diaz P. Cigarette smoking in the HIV-infected population. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2011;8(3):313-319. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1513/pats.201009-058WR] [ Links ]

15. Horvath KJ, Eastman M, Prosser R, Goodroad B, Worthington L. Addressing smoking during medical visits: Patients with human immunodeficiency virus. Am J Prev Med 2012;43(5):S214-S221. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.07.032] [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

C Feldman

(charles.feldman@wits.ac.za)

Accepted 27 August 2013