Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.103 n.11 Pretoria Jan. 2013

GUEST EDITORIAL

Food security: The optimal diet for people and the planet

Leonie Joubert

Science writer. leonie.joubert@scorched.co.za

One morning, in the winter of 2010, I walked into the home of a family living outside Mbabane, Swaziland. There were three young children sitting at the table, aged about six or seven. The table was covered with a plastic tablecloth with really loud fruit printed on it, but there wasn't any fruit in the kitchen. In fact, there wasn't any food in the kitchen at all.

The breakfast that these children had been eating was donated by a local soup kitchen. And it was white bread, torn into chunks, floating in sugar water. The bread had puffed up like marshmallows.

This shocked me. 'Surely this isn't normal, this isn't what most people eat?' Then I got home and started reading and discovered that actually, around southern Africa, thousands and thousands of children start their day like this, every day: eating carbohydrates, washed down with sugar water.

I'm a science writer. For the past ten years I've been telling stories about climate change, energy issues, invasive species ... and in the past four years I decided to turn this sustainability focus on the issue of food. I wanted to understand what 'food security' means for us, here in South Africa (SA), when over half of us live in cities, far from the soil that gives us our beef burgers and our bunny chows and our southern-style fried chicken.

But I discovered that there's a problem with how we view this vague notion of food security, as we grapple with the problem of how to feed nine billion people by the middle of this century, when we have limited soil, water, nutrients, fossil fuels, atmospheric space ...

Here's the problem: right now, we focus so much on how to optimise calories per hectare, to keep up with the growing demand for food; it's all about big production, large scale agriculture, more output, more output, more output ... but we don't ask what we're doing with those calories

The hungry season

The United Nations says that a community is food secure when 'all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life'.

What does this mean for real people in real homes? I travelled around SA, visiting families, in different cities, trying to understand precisely this.

What I found is a broader story about hunger, and malnutrition, in a world where we are surrounded by food: for people in the city, it's not about whether there's enough food around. In fact, it's everywhere. It's about how we access that food, and what choices we make when we get that food. One in five SA kids is so poorly nourished, that they will probably arrive at school with a lower IQ, perform poorly in school, and emerge from school less employable. According to the World Bank, this will shave 10% off a person's earning potential through the course of their life.

The city makes us fat and sick: over half of all South Africans over the age of 15 are overweight or obese. Why? The reasons are varied and unexpected. Food is a commodity - usually found in supermarkets, so the way that cities are laid out creates food oases and food deserts. To complicate matters further, there are cultural perceptions about 'sophisticated' branded foods, v. 'peasant' diets. And on top of all this, the modern food industry has designed foods to appeal to our addiction to fats, sugar and salt.

Meal for the day

Mostly, when we talk about 'food security', we think about it in terms of agriculture: are our big commercial farmers thriving? Are subsistence farmers getting fertilisers and seeds? Are people growing veggies in the city?

But I wanted to understand what this vague term, food security, means at a household level.

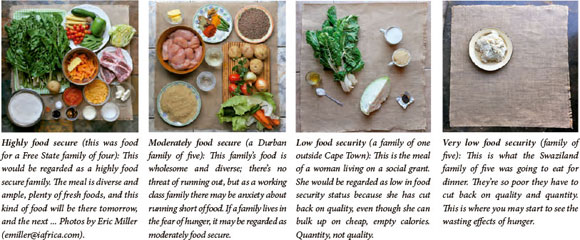

Maybe the pictures below will help explain what I mean a bit better.

Each family I visited during this research was asked to set out the raw ingredients for their main meal of the day. These illustrate, nicely, how the Human Sciences Research Council here in SA defines food security at a household level.

Hidden hunger

This is why malnutrition in the city context is called the hidden hunger: because there's so much cheap, energy-dense, but often unhealthy or low-nutrient food around us. People can bulk up on calories, put on weight and look like they have plenty of food, but they may still be malnourished at a micronutrient level.

Conclusion

What did I learn from this? Well, that the food system is broken.

The food industry has benefited from our addiction to certain highly processed foods. But in many cases the state has had to pick up the healthcare tab in terms of treating the obesity, diabetes, heart disease and cancers associated with eating this diet.

In environmental law, there's the principle of 'the polluter pays'. If you're a mining company and you pollute a wetland, in theory you're responsible for cleaning it up.

It's time we started seeing certain elements of the food industry as a polluter of the nutritional landscape and we need to find a way to make them contribute to cleaning up the damage.

Waste and sustainability

One-third of all food produced for human consumption goes to waste at some point between the farm and the fork. One third. This isn't just a waste of the calories and nutrients in the food. It's a waste of the soil, water, atmospheric space and nutrients that were used to farm those calories.

Again, when we talk about how to feed the world's growing population, on limited land, we seem to talk about how to optimise calories per hectare; how to get more food off the same amount of soil. But we're not asking what we do with those calories.

Is it not as wasteful - more so, perhaps - to take these good, healthy calories from the farm, which were environmentally very costly to produce, and put them through an industrial food process that turns them into dead food, so-called empty calories, that leave us fat and sick and malnourished?

Sustainability

When we talk about carbon footprints and food, we focus a lot of attention on meat and dairy.

It's true, relative to plant calories, that animal calories are more environmentally costly because of how much water, land and atmospheric space they demand. And that's before we've even considered the ethics of industrial animal farming. And animal calories are also much more expensive to buy.

But if a diet that is high in sugar, refined carbohydrates and processed foods is making us fat and sick, surely this isn't sustainable either for our health or for the planet?

What is the optimal diet for both our health and the planet? To figure this out, we need three things:

- To see sugar as the new tobacco. It's toxic, it's addictive, and it's hidden away almost throughout our diet.

- Evidence-based research to inform legislation that is free of the lobbying influence of the food industry. The medical fraternity is in agreement: self-regulation by the food industry hasn't worked. The free market system has failed us. Profits will always prevail.

- To calculate the true cost of food. When the cost of food reflects the free environmental services used to produce that food, and when the health implications of eating that food are factored in, pricing these 'externalities' into the final cost of food will make processed and refined foods much more expensive, relative to 'real' wholesome foods.

It's time to stop focusing so intently on producing more calories to feed our growing population, and start questioning how we kill those calories through our modern food-processing systems. Right now, because of our addiction to processed, energy-dense, sugary and carbohydrate-dense foods, we're eating ourselves, and the environment, to death.