Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versión impresa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.103 no.6 Pretoria jun. 2013

GUIDELINE

Spinal cord stimulation for the management of pain: Recommendations for best clinical practice

A consensus document prepared on behalf of Pain SA in consultation with the South African Spine Society, the Neurological Society of South Africa, and the South African Society of Anaesthesiologists, with guidance from the British Pain Society. These recommendations have been produced by a consensus group (below) of relevant healthcare professionals, and refer to the current body of evidence relating to spinal cord stimulation (SCS)

Dr M Raff, BSc, MB ChB, FCA (SA): Immediate Past President Pain SA, South African Society of Anaesthesiologists (Correspondence)

Dr R Melvill, MB ChB, FCS (Neurosurgery) SA: Continental Vice President World Society for Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery, Society of Neurosurgeons of South Africa

Dr G Coetzee, MB ChB, M Med (Neurosurgery): Exco Member of SA Spine Society (Academic affairs), Society of Neurosurgeons of South Africa

Dr J Smuts, MB ChB, MMed (Neurol), FCN (SA) (by peer review): President Pain SA, Neurological Association of South Africa

ABSTRACT

Spinal cord stimulation (SCS) is an accepted method of pain control. SCS has been used for many years and is supported by a substantial evidence base. A multidisciplinary consensus group has been convened to create a guideline for the implementation and execution of an SCS programme for South Africa (SA). This article discusses the evidence and appropriate context of SCS delivery, and makes recommendations for patient selection and appropriate use. The consensus group has also described the possible complications following SCS. This guideline includes a literature review and a summary of controlled clinical trials of SCS.

The group notes that, in SA, SCS is performed mainly for painful neuropathies, failed back surgery, and chronic regional pain syndrome. It was noted that SCS is used to treat other conditions such as angina pectoris and ischaemic conditions, which have therefore been included in this guideline. These recommendations give guidance to practitioners delivering this treatment, to those who may wish to refer patients for SCS, and to those who care for patients with stimulators in situ. The recommendations also provide a resource for organisations that fund SCS. This guideline has drawn on the guidelines recently published by the British Pain Society, and parts of which have been reproduced with the society's permission.

These recommendations have been produced by a consensus group of relevant healthcare professionals. Opinion from outside the consensus group has been incorporated through consultation with representatives of all groups for whom these recommendations have relevance. The recommendations refer to the current body of evidence relating to SCS. The consensus group wishes to acknowledge and thank the task team of the British Pain Society for their help and input into this document.

Contents

1. Executive summary

2. Need for recommendations

3. Scientific rationale

4. Evidence

5. SCS: Appropriate context for delivery

6. Patient selection

7. Timing

8. Techniques of stimulation

9. The procedure

9.1 Preoperative assessment and preparation

9.2 The theatre environment

9.3 Post-anaesthesia care and ward management

9.4 Discharge and ongoing care

10. Special precautions

11. Complications of SCS

12. Patient information

13. Audit

Spinal cord stimulation (SCS) is a form of therapy with a supportive evidence base, and has been used for the treatment of pain since 1967. It is strategically aimed at reducing the unpleasant sensory experience of pain and the consequent functional and behavioural effects that pain may have. When SCS is used to treat patients with chronic pain, it is important that the treatment is delivered within the context of a full understanding of the impact that pain has upon the patient, including its effect on quality of life. Pain can and does affect patients' psychological well-being and social functions. These recommendations give guidance to practitioners delivering this treatment, to those who may wish to refer patients for SCS, and to those who care for patients with stimulators in situ. The recommendations also provide a resource for organisations that fund SCS.

1. Executive summary

1.1. Persistent pain is common. Whereas acute pain may only impact by interrupting current activity, episodic and persistent pain is likely to interfere with one or more aspects of a person's life and to affect his or her sense of identity.

1.2. There is clinical evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to support the use of SCS for pain from failed back surgical syndrome (FBSS), complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), neuropathic pain, and ischaemic pain. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) published guidance on SCS for chronic pain of neuropathic or ischaemic origin in 2008 (ref - TA 159). It recommended SCS for severe, prolonged pain responsive to a trial of stimulation in FBSS, CRPS, and neuropathic pain. NICE concluded that there was insufficient evidence of cost-effectiveness to recommend the use of SCS outside of controlled trials in ischaemic pain. We concur that further high-quality research on the use of SCS for chronic pain of ischaemic origin is required.

1.3. Not all patients are suitable for SCS.

1.4. A multidisciplinary pain-management team is the most appropriate context in which to provide SCS.

1.5. Not all patients will have the resources to receive SCS therapy, but this does not detract from the evidence supporting its use. It remains an appropriate form of therapy.

1.6. Members of the team must include clinicians competent to deal with the complications of SCS.

1.7. SCS may be delivered in parallel with other therapies and should be used as part of an overall rehabilitation strategy.

1.8. Techniques of SCS vary. Clinical teams must have and maintain the competencies needed to offer the most appropriate technique according to an individual patient's needs.

1.9. Clinicians performing this intervention should insert a sufficient number of SCS systems to maintain competence (see 5.8).

1.10. SCS must be performed in an operating theatre environment suitable for implant work, with appropriate anaesthesia and post-anaesthesia care facilities. Patients must have comprehensive access to advice if they experience problems with the stimulating system.

1.11. The most common organism to infect SCS systems is Staphylococcus aureus.

1.12. SCS is a long-term treatment for a chronic condition, and appropriate infrastructure for ongoing surveillance and support must be in place.

1.13. The compatibility of SCS with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is problematic. While there have now been small series of cases reported without problems, concerns remain and other imaging modalities should be used if at all possible. If MRI is required, the advice of a radiologist should be sought and, depending on imaging site and sequencing, imaging may be possible. However, at present, the majority of radiologists would not advise using MRI with an SCS in situ.

2. Need for recommendations

2.1. Persisting pain occurs in up to one-half of the adult population at some time in their lives. One in 10 adults with persisting pain would describe themselves as being severely disabled by it. Most patients with chronic pain can be managed in primary care, but some need specialised, multidisciplinary assessment and management.

2.2. Patients who are referred to a pain service have frequently seen a number of other secondary-care specialists and have usually been extensively investigated.

2.3. Multidisciplinary pain services should offer patients a range of evidence-based interventions. It is rarely possible to provide complete pain relief. Patients should also be offered advice on self-management and coping strategies, in tandem with any interventions.

2.4. Persisting pain is difficult to treat, and some patients will continue to experience intrusive and distressing symptoms despite a variety of surgical and electro-thermal interventions.

2.5. SCS may be helpful in carefully selected patients. However, many patients will not be helped by SCS.

2.6. Some indications for SCS are well-established (e.g. FBSS, CRPS, neuropathic pain, refractory angina pectoris (RAP), peripheral vascular disease), and others are emerging (e.g. visceral pain, interstitial cystitis). As knowledge and expertise develop, the techniques change and may be refined.

2.7. At the time of writing, many patients in SA are refused therapy with SCS due to lack of funds, or to medical assessors' lack of knowledge on the subject. This does not imply that this form of therapy is not well-established or not supported by good scientific studies.

2.8. The recommendations will:

a) Guide healthcare professionals regarding:

Whom to refer

Whom not to refer

What to tell patients

How to look after patients who have had SCS implanted

How to deal with complications after SCS implantation.

b) Promote best clinical practice for clinical teams involved in providing SCS, to enable them to:

Select patients appropriately

Prepare patients for the therapy

Deliver SCS safely with minimal morbidity

Optimise outcomes

Provide appropriate continuing care.

c) Allow patients to make an informed decision.

d) Inform commissioners of healthcare services and medical funders.

3. Scientific rationale

3.1. The use of stimulation techniques in modern pain medicine dates from the publication of the gate theory of Melzack and Wall in 1965, which described how stimulating neural pathways carrying innocuous (non-painful) information could influence the onward transmission of noxious information in the nervous system.

3.2. Although the introduction of SCS was inspired by the gate theory, its mechanism of action involves more than a direct inhibition of pain transmission in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. If this were the principal mode of action, then SCS would control nociceptive pain, and this is not generally the case. Pain modulation by SCS also involves supra-spinal activity via the posterior columns of the spinal cord, probably recruiting endogenous inhibitory pathways. There is also a pronounced autonomic effect, though the mechanisms of this are not fully understood.

3.3. The preservation of topographically appropriate posterior column function seems to be necessary for SCS to be effective, but there is debate regarding which elements are necessary and to what degree.

4. Evidence

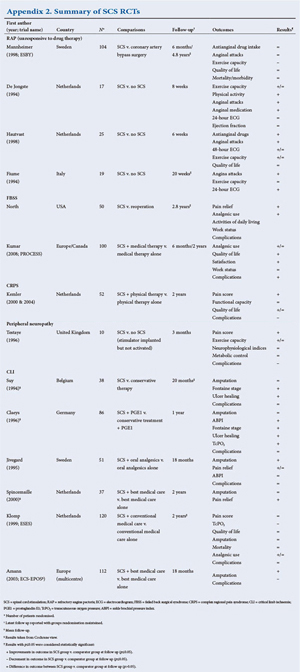

4.1. RCTs of SCS have been undertaken for FBSS, complex CRPS type 1, RAP, and chronic critical limb ischaemia (CLI). A summary of these RCTs and their findings is listed in Appendix 2. In addition to RCT evidence, systematic reviews of SCS have included case series and observational comparisons, particularly for FBSS and CRPS (see Appendix 2). It should be noted that present funding models in SA include only FBSS, CRPS, and some peripheral neuropathies including post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN) and diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN). These guidelines do include some data on the other described pathologies but shall be more focused on the former conditions.

RCTs demonstrate that SCS is more effective for radicular (limb) pain following spinal surgery than either reoperation or management by nonsurgical therapy.

4.2. NICE published guidance on SCS for chronic pain of neuropathic or ischaemic origin in 2008 (ref - TA 159). With provisos regarding the severity and duration of pain and a trial of stimulation after multidisciplinary assessment, SCS is recommended as a treatment option for adults with chronic pain of neuropathic origin. This recommendation was based on RCT data and robust cost-effectiveness analyses for trials in FBSS and CRPS. The recommendation was extended to include all causes of chronic pain of neuropathic origin on the advice of nominated specialists. SCS is not, however, recommended for chronic pain of ischaemic origin, except in the context of research as part of a clinical trial.

4.3. NICE felt unable to recommend SCS for chronic pain of ischaemic origin for two reasons: lack of high-quality RCT data, and insufficient data to support robust economic modelling. Functional outcomes were considered in addition to improvements in pain levels.

4.4. In the case of CLI, NICE acknowledged that non-randomised evidence suggests there may be functional benefit for certain sub-groups of people. The evidence for improvement in health-related quality of life was not robust, and it was not possible to perform a cost-effectiveness analysis.

4.5. With regard to RAP, NICE assessed that the available data did not allow accurate identification of the population to be treated, or the available comparator treatments. The committee accepted that SCS was as effective as comparator treatments in the included studies. Again, no cost-effectiveness analysis was possible.

4.6. We concur with NICE that further high-quality research on the use of SCS in chronic pain of ischaemic origin is required.

5. SCS: Appropriate context for delivery

5.1. Pain interferes with physical function and is often associated with psychological problems. All patients being considered for SCS must be assessed with regard to physical, psychological, and social functioning.

5.2. An important approach to the treatment of pain is to attempt to modulate the unpleasant sensory experience by reducing the intensity, duration and frequency with which pain is felt. Medication, nerve blocks, physical therapies and SCS are all strategies used to achieve this outcome. SCS should not be considered as a first line of therapy, and other non-invasive options for treating the pain should be considered first.

5.3. Psychological interventions - mainly cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) - are largely focused on mitigating the interference in function that persistent pain induces. Such treatments may be offered in conjunction with SCS.

5.4. Qualitative psychological testing does not predict outcome, but assessment by a psychologist is desirable to assess the patient's beliefs, expectations, and understanding of the treatment in relation to the condition.

5.5. A multidisciplinary pain-management team is the most appropriate context in which to provide SCS. Such a team should be able to deliver a range of therapies for pain.

5.6. The team will usually comprise several professionals. Members may include a consultant in pain medicine and one or more consultants from other relevant specialties, e.g. neurosurgery, spinal surgery, cardiology, or vascular surgery. Other members of the team might include psychologists, physiotherapists, and nurse specialists in pain management. The team must have access to a spinal surgeon or neurosurgeon competent to deal with the complications of SCS.

5.7. Clinicians performing the SCS interventions must understand the multidisciplinary management of pain. They must have and maintain relevant surgical competence in insertion of the SCS system and management of complications such as infection. This will usually be in the form of a consultant in pain medicine, neurosurgeon, or spinal surgeon.

5.8. The competence of the implanter and the activity and competence of the team must be maintained. Where a new service is being established, there should be evidence of progression toward an annual caseload that will maintain competence, or the opportunity to regularly work within other units that have a high level of activity.

5.9. SCS is a long-term therapy. Teams must have appropriate arrangements for ongoing patient care, including availability to investigate and manage potentially serious problems such as neurological deficit, bleeding or infection. SCS is a significant commitment for patients and their healthcare team, and it is not usually appropriate for a single consultant to manage this therapy without the support of colleagues.

6. Patient selection

6.1. Patients must have an up-to-date assessment in relation to the indication for SCS.

6.2. History and physical examination should be detailed.

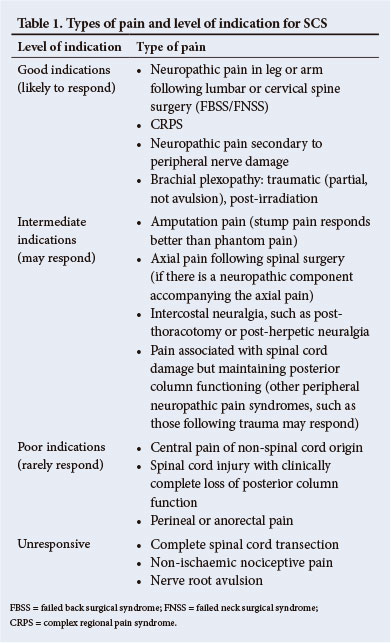

6.3. The indications for SCS are summarised in Table 1.

6.4. The use of SCS for other conditions such as pelvic and visceral pain has been described. Its use in these and other emerging indications should carefully be audited.

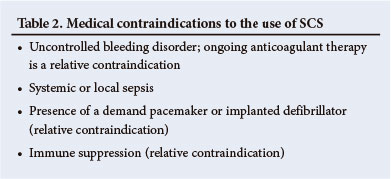

6.5. Contraindications to the use of SCS are summarised in Table 2.

6.6. Considerations regarding surgical insertion of plate electrodes are summarised in Table 3.

6.7. Many patients, such as those with pain following spinal surgery, will present a mixed neuropathic/nociceptive picture. Patients should be told that SCS will probably only help part of their pain. Teams offering SCS must be able to deliver appropriate additional therapies, including pain management programmes.

6.8. Physical and psychological co-morbidity does not preclude treatment with SCS. Patients with concurrent physical or mental illness should be assessed in close conjunction with relevant clinical teams. Cognitive impairment, communication problems, or learning difficulty resulting in failure to understand the therapy are not reasons to exclude patients from SCS, but these patients must have a cognizant caregiver and adequate social support.

6.9. The management of children being considered for SCS should be in conjunction with a specialised multidisciplinary children's pain management team.

7. Timing

7.1. SCS may be delivered in conjunction with other therapies such as medication and psychologically based therapies. If there is significant psychological distress identified at assessment, such patients may benefit from individual psychological therapy (e.g. CBT) before proceeding to SCS. For those patients who may also benefit from a pain management programme, it is preferable to provide that treatment before SCS.

7.2. SCS should be considered early in the patient's management when simple first-line therapies have failed. SCS should not necessarily be considered a treatment of last resort.

7.3. Cognitive impairment resulting in failure to understand the therapy is not a reason to exclude patients from SCS, but these patients must have a cognisant carer and adequate social support.

8. Techniques of stimulation

8.1. Stimulation of the spinal cord is by an implanted electrode powered by an implanted pulse generator (IPG). Electrodes may be inserted percutaneously via an epidural needle or surgically implanted via laminotomy. Electrodes may be bipolar or multipolar, and multiple electrodes may be used. Pulses are generated by a fully implantable battery-powered device. Rechargeable battery systems are now available and may be preferred for some patients such as those who require high current use (including systems with multiple electrodes), as these batteries have been proven to be cost-effective.

8.2. Electrodes must be placed to elicit paraesthesia that covers the region of reported pain.

8.3. It is recommended that percutaneous electrodes be placed under a local anaesthetic with minimal sedation. This optimises electrode placement and reduces the risk of inadvertent neural trauma.

8.4. Surgical electrodes require open surgery (laminotomy or partial laminectomy) for placement. This is usually carried out under a general anaesthetic. Such electrodes are less likely to be dislodged.

8.5. The electrode/s should be connected temporarily to an external stimulating device before proceeding to insertion of an IPG. This allows the patient to undergo a period of trial stimulation during which time pain relief, improvement in function, and reduction in medication may be assessed. If the outcome of the trial is favourable, then the patient may wish to proceed to IPG insertion.

8.6. The same team should carry out trial stimulation and definitive implantation.

8.7. Following IPG insertion, the patient may switch the device on and off with a hand-held programmer and may vary voltage and frequency within physician-determined limits.

8.8. IPG battery life is variable, but is usually between 2 and 8 years depending on the pattern of use and the output required. Rechargeable batteries with increased longevity are now available.

8.9. Centres offering SCS to patients should ensure that the service is appropriately funded to support ongoing system maintenance, including the need for IPG replacement in those patients who do not have a rechargeable system in situ, and the possible need for lead or system revision. Patients must be made aware of all matters relating to funding prior to any SCS procedure.

9. The procedure

9.1 Preoperative assessment and preparation

9.1.1. Patients must be investigated appropriately to determine their fitness to undergo surgery and anaesthesia or sedation.

9.1.2. The most common organism to infect SCS systems is S. aureus.

9.1.3. The patient and operator should agree preoperatively on the proposed position of the IPG.

9.1.4. There is little published evidence regarding the use of antibiotic prophylaxis for SCS. Infection of an SCS system can be a significant problem and therefore its consequences justify the use of antibiotic prophylaxis. Antibiotics should be given as a single intravenous dose prior to starting the procedure. Appropriate cover for S. aureus should be ensured.

9.2 The theatre environment

9.2.1. Standard operating and post-anaesthesia care facilities must be available.

9.2.2. The operating theatre must be suitable for implant work. A laminar flow environment is suggested.

9.2.3. X-ray screening is mandatory for percutaneous lead placement.

9.2.4. A practitioner skilled in programming and trialing SCS must be present for the percutaneous procedures.

9.3 Post-anaesthesia care and ward management

9.3.1. Programming the SCS should not begin until the patient is fully conscious.

9.3.2. Ward staff should be familiar with the aims and procedure of SCS, the condition that it is being used to manage, and the potential complications that may arise.

9.3.3. The post-operative observation regimen should consider potential complications such as spinal cord compression, neurological injury, bleeding, and infection.

9.3.4. Ward staff should be able to seek advice from a member of the implant team at any time.

9.4 Discharge and ongoing care

9.4.1. Adequate arrangements must be made for the implant team to conduct surveillance and follow-up; the patient should be able to contact an appropriate and experienced professional at any time.

9.4.2. Referring physicians must be given advice about all patients who are sent home after SCS implant.

9.4.3. In the event of complications related to the SCS or other pathology, there should be established relationships with other relevant disciplines such as spinal surgery and neurosurgery, microbiology and neuroradiology.

9.4.4. SCS is a long-term treatment for a chronic condition. Patients with non-rechargeable systems will need IPG replacement at some stage. Mechanisms should be in place to predict when this is likely to occur, so that, with planning, SCS function can be restored promptly.

9.4.5. If patients move beyond a reasonable travelling distance from the implanting centre, systems must be in place to transfer their care appropriately to other physicians.

10. Special precautions

10.1. Unipolar diathermy should be avoided in patients with SCS in situ. If its use is unavoidable, the reference plate should be positioned so that the SCS components are outside the electrical field of the diathermy.

10.2. The interaction of MRI and SCS is complex. The magnetic field may cause leads to move, resulting in loss of effect or neural damage, or heat the implant components, resulting in discomfort, tissue damage, or software malfunction. In addition, the location of the leads in relation to the site of imaging interest may corrupt the image. Patients with SCS in situ who need investigation with MRI may pose specific problems that should be discussed with an experienced neuro-radiologist. If there is any doubt about the compatibility, then alternative imaging (such as computed tomography (CT) scan or myelography) should be performed. It has been established that if MRI studies are unavoidable, then the IPG should be switched off during the scans and thereafter checked for programming errors.

10.3. The presence of a cardiac pacemaker is a relative contraindication to SCS. Most contemporary pacemakers are operated in the demand mode - they monitor intrinsic cardiac activity, and may be inhibited by spontaneous extra-cardiac electrical activity. They may sense extraneous electrical activity from SCS devices and misinterpret it as appropriate cardiac activity. The pacemaker may then either respond by inhibiting pacing or by reverting to an asynchronous pacing mode. Inhibition of pacing can be potentially dangerous for the patient; asynchronous pacing is less serious, but still compromises pacemaker function. In such circumstances, it has been suggested that bipolar pacemaker sensing should be employed, as it is inherently less sensitive to extraneous signals than the unipolar pacing mode.

10.4. Patients should be advised that airport (and other) security systems may be activated by a stimulator. Patients should carry information relating to their SCS in situations where this may be relevant.

10.5. Patients must inform their medical caregivers that they have SCS in place.

10.6. Short-wave diathermy, microwave diathermy, and therapeutic ultrasound diathermy are hazardous in patients with SCS.

10.7. Antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended for patients with SCS systems in situ who are undergoing incidental procedures that may generate bacteraemia.

11. Complications of SCS

11.1. SCS has been used in many thousands of patients worldwide; some clinical centres have reported follow-up of >10 years. Major complications of SCS are rare, but minor ones are common. Most problems are technical, with the most common complication being lead migration. These complications should be discussed during the consent process.

11.2. Neurological damage relating to epidural electrode placement is a rare complication and may occur with both percutaneous and surgical electrodes. Damage may occur directly or from epidural haematoma or infection. These latter complications are reversible if diagnosed and treated promptly, emphasising the importance of postoperative neurological observations by experienced staff. Vigilance and access to early imaging are essential (see 10.2).

11.3. Dural puncture may occur during percutaneous insertion of electrodes. This happens most frequently with the Tuohy needle, but may occur with the guide wire or the stimulating electrode.

11.4. Infection of implanted neurostimulators is a serious problem and must never be ignored. Usually, the infection will not resolve unless the whole SCS system is explanted. Infection of the entire system is rare but can result in epidural abscess with potentially disastrous neurological consequences. In such cases explantation is required.

11.5. Patients should be aware that not only will surgery be necessary to replace a depleted IPG but that it may also be necessary to revise the electrodes or connections.

11.6. Electrode migration (see 11.1) may occur immediately following the procedure, at any time during the trial period or following IPG insertion. Cervical electrodes are more likely to be dislodged than those in the thoracic region. Migration is less likely with surgical electrodes. Recent improvements in anchor designs have been shown to reduce migration.

11.7. Other potential problems include fluid entering the connectors or electrode, lead breakage, and disconnection.

12. Patient information

12.1. The risks and limitations of SCS should be discussed with patients, who should be given written information in a form that they can understand.

12.2. Patients must be aware of the evidence for the efficacy of SCS for the indication in their case.

12.3. Patients should be given information relating to complications and outcomes.

12.4. Detailed information regarding the procedure of SCS insertion, including the operating theatre environment, is necessary.

12.5. Patients should understand that SCS provides benefit only as part of a multidimensional approach to symptom management.

12.6. Patients should understand the need for ongoing care following SCS, including the likelihood of needing further surgery.

12.7. Patients must be given adequate time to consider the benefits and burdens of the technique before consenting to treatment.

13. Audit

13.1. There is currently no national database of SCS patients.

13.2. Local audit of implanted patients is recommended.

13.3. Formal professional communication between implanting centres is strongly recommended.

Conflict of interest. Milton Raff has received research funding and honoraria from medical device and pharmaceutical companies for lectures at conferences, to attend advisory boards, to contribute to publications, and to attend meetings to support professional development. Gerrit Coetzee has received honoraria from Southern Medical and has consulted with Medtronic regarding non-pain-associated devices. Roger Melvill and Johann Smuts declare no competing interests.

Correspondence: M Raff (raffs@iafrica.com)

Correspondence: M Raff (raffs@iafrica.com)

Appendix 1: SCS literature review

Appendix 2: Summary of SCS RCTs