Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versão impressa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.103 no.5 Pretoria Mai. 2013

IZINDABA

'Jack-knife' scrum victim: 8 years on, no payout

Chris Bateman

Santam, one of South Africa's largest insurance companies, has repudiated a R3 million payout claim from a former Stellenbosch schoolboy rugby hooker, whose deliberate 'jack-knife' scrumming tactics temporarily paralysed his opponent and left him with life-long disabilities.

They cite the landmark High Court finding, (confirmed on appeal),'[1] that Alex Roux, the Stellenbosch High School under-19A hooker, 'intentionally and wrongfully' injured his Laborie High School opposite number, Ryand Hattingh. Santam say that this releases them from liability on what was a personal legal liability policy carried by Alex's late father. The insurance giant declined to disclose the full findings of a probe by Professor J C van der Walt, their in-house arbitrator, delict expert and former dean of the law faculty, rector and vice-chancellor at the Rand Afrikaans University.

Ironically, had Hattingh's legal team gone after the coach, school principal and Minister of Sport and Recreation for compensation, they may have won substantial damages more quickly. However, they instead chose to sue Roux after learning of the legal liability policy.

In their repudiation, Santam says this policy provides only for negligent acts, adding that they advanced the defence costs on Roux's behalf (as required by their policy) after Roux Senior told them that his son did not cause the injury or act intentionally. In an e-mail response to a list of Izindaba questions, Professor Van der Walt said that no short term policy exists in the market to provide cover for intentional actions, as this would be 'repugnant to the whole concept of insurance'. He said he provided his views after Hattingh's lawyers made representations to Santam to reconsider their repudiation, adding that Santam's conduct and actions in the litigation, as well as the 'clearly justifiable repudiation' are 'beyond any reproach of possible impropriety, immoral or wrongful conduct'.

Izindaba asked Professor Van der Walt if he could say whether liability for a rugby sports injury would activate only on the basis of negligence and not on the basis of intention (and to give examples), as well as for his opinion on how this might affect Santam's existing policy holders. He said 'intent' is a technical legal concept and does not mean intent 'in the ordinary sense of the word'. It means 'directing your will to the achievement of a particular result and the consciousness of the wrongfulness of the act'. In the relevant Appeal Court ruling, the court 'could have' concluded that Roux did not have intent in the legal sense, in which case his conduct would, in all probability, have been negligent. Because of the intricate legal concepts of intent and negligence, Professor Van der Walt believes that most sports injuries would normally be the result of negligence. However, he emphasised, this has to be proven in individual cases.

Injured player still has claim options

The civil action for a quantum of damages was still being mounted at the time of going to print. Having established Roux's legal 'liability', but finding themselves stymied by Santam, Hattingh's lawyers will now either try and persuade Roux to cede his insurance policy to them so they can take on Santam, or claim damages against a trust left to him by his father, a farmer in the Northern Cape. Roux's father tragically committed suicide after the incident.

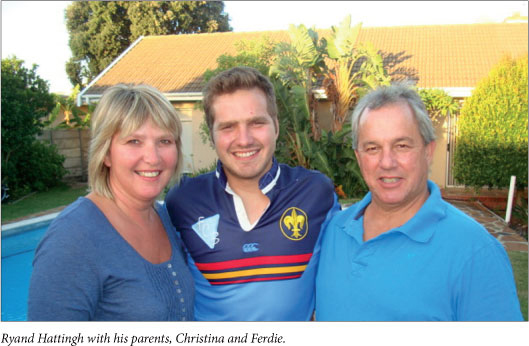

Today Hattingh has limited use of his left hand, loss of feeling on his right-hand side (after major surgery led to his recovery from paralysis, he suffered third-degree burns to his hip without feeling any pain), a left leg 3 cm shorter than the right, and a severely weakened knee. Unable to play any contact sports, he works as a diesel motor mechanic, his plans of becoming a commercial pilot in tatters. Using reports by psychologists, a neurologist, a physiotherapist and a biokineticist, actuaries estimate his previous and future expected therapy and surgical costs, plus disability devices and loss of future earnings, at a total of R9.9 million. Ryand's mother, Christina, is a personal assistant in a provincial government department, while his father, Ferdie, is a junior school teacher and suffers from Guillain-Barré syndrome. Christina told Izindaba that her son's refusal 'to let things get him down' had played a major role in his miraculous recovery, but that he really misses his rugby, and now plays linesman for his younger brother Corne's team. 'He's been told by the doctors that he probably will only work until he's about 45 and that some things will get progressively worse' She said that at 26 years old, her son has less than a year left on her government medical aid scheme (GEMS), and no medical aid is provided by his current employer. 'Luckily we believe in miracles - his recovery for example - so we're hoping things will work out.' She said that she and her son once encountered Alex Roux by chance while on a shopping expedition at Canal Walk near Cape Town. After making 'angry' eye contact Roux 'suddenly turned around and walked the other way'. There had been no other contact between the two boys since the injury.

How it happened

The court record shows that the game was played in good underfoot conditions and that, after one of the first scrums of the match, Hattingh complained to the captain of Laborie, Jan Louis Marais, that Alex had been guilty of 'hanging' in the scrum, which is contrary to the rules of the game. Hattingh was injured in the fourth or fifth scrum of the match, about 10 - 15 minutes after kick-off. He testified that as the forwards were forming for the scrum, Alex shouted the word 'jack-knife'. His evidence was supported by two of his teammates, who were adamant that nothing else was said apart from the word 'jack-knife'. Alex and two of his teammates testified that the code 'jack-knife' was a signal to wheel the scrum and something else was called to indicate to the forwards that they should wheel the scrum to the left or the right - a version of events rejected by the court. Hattingh testified that when the front rows crouched prior to engaging each other, he saw Alex move to his (Alex's) right. This had the effect of blocking the channel into which Hattingh's head was meant to go. He realised that he was in trouble and closed his eyes when the forward packs engaged. The pressure of Alex (and the weight of the Stellenbosch pack behind him) on Hattingh's neck caused Hattingh to scream in pain. The scrum collapsed and he was left lying on the ground, seriously injured.

The replacement hooker, Gawie Alberts, complained to Marais after a scrum (and after Hattingh's injury) that Alex had closed his channel and that he had had difficulty entering it, suffering abrasions to his face as a result. So seriously did Marais take this, that when he spoke to the referee, he said that the referee should 'hou net vir ons asseblief dop, ons wil nie hê nog 'n ou moet seerkry nie' ('please watch us, we don't want another guy getting hurt'). Soon after this Alex changed positions from hooker to prop and the referee decided that from then on all of the scrums would be uncontested.

The verbal court evidence was backed by a video with photographic extracts of the scrum in which Hattingh was injured, and included expert evidence from former Springbok and provincial front-row players, Balie Swart and Mathew Proudfoot, and internationally renowned referee, André Watson. It sparked international media attention and debate about the legal liability of players (other famous rulings on liability include those on malicious biting and punching). The unanimous Appellate Division ruling of five judges was that the high court's factual findings could not be faulted and the conclusion that Roux had acted deliberately was faultless. They found the 'jack-knife' manoeuvre executed by Roux in contravention of the rules, as well as contrary to the spirit and conventions of the game. They also held that Roux must have foreseen that the manoeuvre was likely to cause injury to Hattingh but proceeded to execute it nonetheless.

1. Alex Roux v Ryand Karel Hattingh (636/11) [2012] ZASCA132 (27 September 2012). [ Links ]