Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versión impresa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.102 no.11 Pretoria ene. 2012

RESEARCH

Factors influencing the development of early- or late-onset Parkinson's disease in a cohort of South African patients

C van der MerweI; W HaylettII; J HarveyIV; D LombardV; S BardienIII; J CarrVI

IBSc (Hons). Division of Molecular Biology and Human Genetics, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University

IIBSc (Hons). Division of Molecular Biology and Human Genetics, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University

IIIPhD. Division of Molecular Biology and Human Genetics, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University

IVMCom, PhD. Centre for Statistical Consultation, Stellenbosch University

VDip (Nursing), BaCur. Division of Neurology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University

VIMB ChB, PhD. Division of Neurology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson's disease (PD) contribute significantly to global disease burden. PD can be categorised into early-onset PD (EOPD) with an age at onset (AAO) of <50 years and late-onset PD (LOPD) with an AAO of >50 years.

AIMS: To identify factors influencing EOPD and LOPD development in a group of patients in South Africa (SA).

METHODS: A total of 397 unrelated PD patients were recruited from the Movement Disorders Clinic at Tygerberg Hospital and via the Parkinson's Association of SA. Patient demographic and environmental data were recorded and associations with PD onset (EOPD v. LOPD) were analysed with a Pearson's Chi-squared test. The English- and Afrikaans-speaking (Afrikaner) white patients were analysed separately.

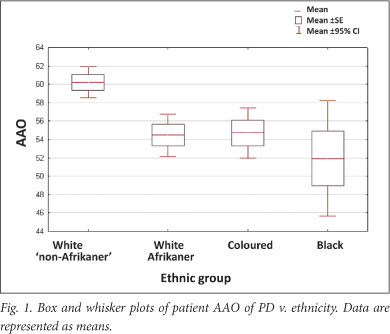

RESULTS: Logistic regression analysis showed that ethnicity (p<0.001) and family history (p=0.004) were independently associated with AAO of PD. Average AAO was younger in black, coloured and Afrikaner patients than English-speaking white patients. A positive family history of PD, seen in 31.1% of LOPD patients, was associated with a younger AAO in the study population.

CONCLUSIONS: These associations may be attributed to specific genetic and/or environmental risk factors that increase PD susceptibility and influence the clinical course of the disorder. More studies on PD in the unique SA populations are required to provide novel insights into mechanisms underlying this debilitating condition.

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a debilitating neurodegenerative disorder with no known cure. PD is prevalent in approximately 1% of individuals aged >65 years, increasing to 4% in individuals aged >80 years.1 In a study of the most populous countries in Western Europe and the world (including Germany, France, Nigeria and Japan), the number of PD-affected individuals in 2005 was estimated to be 4.1 - 4.6 million. This figure is expected to double by 2030.2 PD epidemiological data are not available for South Africa (SA).

PD aetiology is not fully understood, but is thought to involve an interaction between genetic and environmental risk factors.3 Important insights into genetic causes have been made, largely due to the discovery of causative mutations in several genes.4

PD cases can be subcategorised based on age at onset (AAO): early-onset PD (EOPD) with an AAO <50 years, and late-onset PD (LOPD) with an AAO >50 years.5 EOPD and LOPD differ in clinical presentation and underlying genetic aetiology. EOPD exhibits a slower disease progression, a good response to levodopa therapy and additional signs such as dystonia and prominent levodopa-induced dyskinesias.6 Mutations in causative genes that are inherited in an autosomal recessive manner (e.g. parkin and PINK1) are associated with familial EOPD, whereas autosomal dominant mutations (in SNCA and LRRK2) typically contribute to familial LOPD.4

Although old age is a significant risk factor for PD, additional factors include a positive family history and environmental elements such as drinking well-water, living in a rural area, farming and pesticide exposure.7 Exposure to the insecticide rotenone,8 the herbicide paraquat9 and the neurotoxin 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)10 have been shown experimentally to cause mitochondrial dysfunction and subsequent parkinsonism in laboratory animals. Studies investigating PD associations with chemical products, such as metals, solvents, paints and other chemicals, have shown conflicting findings.11 Notably, cigarette smoking and coffee consumption are thought to protect against PD development.12,13

We aimed to identify factors influencing EOPD and LOPD development in a group of 397 PD patients in SA.

Methods

The study was approved by the Committee for Human Research at the University of Stellenbosch (2002/C059). A total of 397 unrelated PD patients were recruited, with written informed consent, from the Movement Disorders Clinic at Tygerberg Hospital, a tertiary referral hospital in Cape Town, and through the Parkinson's Association of SA. PD diagnosis was made by a movement disorder specialist according to the UK Parkinson's Disease Society Brain Bank Research criteria. Participants were recruited as part of ongoing genetics research investigating the underlying genetic basis of PD in different ethnic groups in SA.

Recruited ethnic groups14 included white (288; 72.5%), coloured (86; 21.7%), black (18; 4.5%) and Indian/Asian (5; 1.3%). Ethnicity was self-reported. White Afrikaner patients were analysed separately to the 'non-Afrikaner' white patients. The Afrikaner population originated in SA and descended from a group of 2 000 mainly male progenitors who arrived in the Cape in the 17th and 18th centuries;15 they were predominantly of Dutch, German and French origin. Initially, due to cultural, religious and language differences, the Afrikaner population remained largely isolated. Indicative of their unique ancestral lineage, several rare inherited disorders such as porphyria variegata and Gaucher's disease occur at unusually high frequencies in this population, possibly due to genetic founder effects.16 The coloured ethnic group is an admixture of indigenous African, European, South Asian and Indonesian populations.17

Sampled clinical data included AAO and family history of PD; the latter defined as having >1 family member (first-, second- or third-degree relative) with possible PD. Environmental data for each index patient, collected with a questionnaire, were recorded as part of a collaboration with the international Genetic Epidemiology of Parkinson's Disease (GEO-PD) Consortium. Information was obtained on current and previous occupation, smoker status, coffee consumption and pesticide exposure prior to PD diagnosis. Optional responses were 'ever' or 'never'; 'ever' was defined as having smoked >1 cigarette per day, consumed >1 cup of coffee per day, and broadly, as the use of a herbicide, fungicide or insecticide, prior to PD onset.

Data were analysed descriptively, using means and standard deviations for continuous data and frequencies counts and percentages for categorical data. Associations between AAO (binary classification: <50 years of age v. >50 years of age) and demographic and environmental variables were analysed with a Pearson's Chi- squared test. In cases of small cell frequencies, a Fisher's Exact test was used to assess association. A multiple logistic regression was used to test the association between demographic variables and AAO after adjusting for the presence of other predictor variables. Where the actual (continuous) AAO was analysed, a Student's t-test was used. A significance level of 5% was applied throughout.

Results

A total of 397 patients were recruited over a 5-year period (2007 -2011) (Table 1); 62.5% (248) were male and 34.8% (138) had a family history of PD. For the first 3.5 years, the study focussed mainly on recruiting EOPD patients and/or those with a positive family history of PD (as these were thought to harbour a greater genetic component). Subsequent to the identification of mutations associated with LOPD, criteria also included LOPD and sporadic (non-familial) cases.

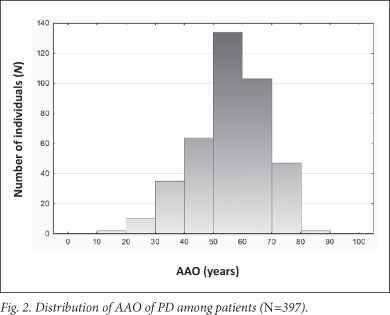

A significant association was found between AAO and ethnicity; the black, coloured and white Afrikaner patients had a younger mean AAO than the 'non-Afrikaner' whites (p=0.00038) (Table 1 and Fig. 1). The black patients exhibited the youngest AAO but were limited in numbers (n=18); this finding requires verification. A positive family history was associated with a younger AAO (p=0.01445). No association was found between AAO and gender or an environmental factor (cigarette smoking, coffee drinking, pesticide use and chemical exposure) (Table 1). This may be attributed to small sample sizes; relevant data were not available for every participant. Logistic regression analysis showed that ethnicity and family history were independently associated with AAO (p<0.001 and p=0.004, respectively). Mean AAO was 56.8 years (SD ±12.4; 95% CI 55.6 - 58.0, range 17 - 87) (Fig. 2), emphasising that PD also occurs in comparatively young individuals.

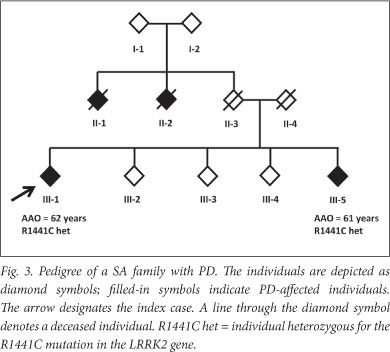

A positive family history was found in 31.1% of LOPD patients (Table 1). This may be an underestimate: one LOPD patient (individual Fig 3) initially reported no family history. However, we previously identified a disease-causing mutation (R1441C in the LRRK2 gene) in the patient (unpublished data), which led to a subsequent family follow-up. A sibling of the patient (individual III-5) was shown to harbour the mutation and later clinically diagnosed with PD; the sibling reported 2 other possibly affected individuals who were deceased (individuals II-1 and II-2).

Discussion

This study raises awareness about the relatively high frequency of PD cases with young onset and a positive family history among SA patients. This retrospective investigation demonstrated that the black, white Afrikaner and coloured patients had a younger AAO than 'non-Afrikaner' white patients. A positive family history was also associated with a younger AAO. These associations may be attributed to specific genetic and/or environmental risk factors that increase PD susceptibility and influence the clinical course of the disorder.

Approximately one-third of LOPD patients exhibited positive family histories, challenging the assumption that LOPD manifests sporadically, and demonstrating a possible genetic contribution. We contend that positive family histories are often underreported and, consequently, underestimated. The initial analysis of family history of PD may be misleading unless further intensive follow-up and genetic work-up of the families is performed.

In this study, gender had no effect on AAO, in accordance with the literature.18 However, 62.5% of patients were male, possibly due to recruitment bias. Some studies have shown that men are 1.5 times more likely to develop PD than females.19 However, this trend is not consistent across studies.

We found no significant association between cigarette smoking, coffee drinking, pesticides or hazardous chemicals exposure with AAO of PD, despite work by others showing the contribution of these factors to PD susceptibility.13,20 Exposure to environmental risk factors may increase PD susceptibility without necessarily affecting AAO. A lack of exposure data for unaffected control individuals precluded any tests for such an association.

Study limitations include the relatively small samples sizes (particularly for the black group) and a lack of environmental variable data for every participant. Furthermore, recruitment bias may have been introduced, although it is unclear what influence this may have had on participant AAO. Study patients were part of an ongoing research project investigating PD genetic aetiology; they were recruited from a tertiary academic centre and various PD support groups of the Parkinson's Association of SA. Coloured patients were recruited primarily from Tygerberg Hospital, 'non-Afrikaner' white patients were recruited predominantly from support groups, and white Afrikaners were recruited almost equally from both sources.

Conclusion

There is little knowledge on the environmental and genetic factors associated with PD in SA. Although our findings are preliminary, studies on unique and diverse SA populations are needed to provide novel insights into the risk factors and pathogenesis underlying this debilitating disorder.

Acknowledgements. We gratefully acknowledge participant involvement and the following funders: Medical Research Council of SA, the Harry and Doris Crossley Foundation, and the University of Stellenbosch.

References

1. De Lau LM, Breteler MM. Epidemiology of Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol 2006;5(6):525-535. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70471-9]

2. Dorsey ER, Constantinescu R, Thompson JP et al. Projected number of people with Parkinson disease in the most populous nations, 2005 through 2030. Neurology 2007;68(5):384-386. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000247740.47667.03]

3. Sherer TB, Betarbet R, Greenamyre JT. Environment, mitochondria and Parkinson's disease. Neuroscientist 2002;8(3):192-197. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1073858402008003004] [ Links ]

4. Gasser T. Mendelian forms of Parkinson's disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009;1792(7):587-596. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.12.007] [ Links ]

5. Marder KS, Tang MX, Mejia-Santana H, et al. Predictors ofparkin mutations in early- onset Parkinson's disease: the consortium on risk for early-onset Parkinson's disease study. Arch Neurol 2010 67(6):731-738. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archneurol.2010.194] [ Links ]

6. Schrag A, Schott JM. Epidemiological, clinical and genetic characteristics of early-onset parkinsonism. Lancet Neurol 2006;5(4):355-363. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70411-2]

7. Priyadarshi A, Khuder SA, Schaub EA, Priyadarshi SS. Environmental risk factors and Parkinson's disease: A metaanalysis. Environ Res 2001;86(2):122-127. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/enrs.2001.4264; [ Links ]

8. Betarbet R, Sherer TB, Mackenzie G, Garcia-Osuna M, Panov AV, Greenamyre JT. Chronic systemic pesticide exposure reproduces features of Parkinson's disease. Nat Neurosci 2000;3(12):1301-1306. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/81834]

9. McCormack AL, Thiruchelvam M, Manning-Bog AB, et al. Environmental risk factors and Parkinson's disease: Selective degeneration of nigral dopaminergic neurons caused by the herbicide paraquat. Neurobiol Dis 2002;10(2):119-127. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/nbdi.2002.0507] [ Links ]

10. Przedborski S, Tieu K, Perier C, Vila M. MPTP as a mitochondrial neurotoxic model of Parkinson's disease. J Bioenerg Biomembr 2004;36(4):375-379. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:JOBB.0000041771.66775.d5] [ Links ]

11. Gorell JM, Peterson EL, Rybicki BA, Johnson CC. Multiple risk factors for Parkinson's disease. J NeurolSci 2004;217(2):169-174. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2003.09.014]

12. Morens DM, Grandinetti A, Reed D, White LR, Ross GW. Cigarette smoking and protection from Parkinson's disease: false association or etiologic clue? Neurology 1995;45(6):1041-1051. [ Links ]

13. Hernan MA, Takkouche B, Caamano-Isorna F, Gestal-Otero JJ. A meta-analysis of coffee drinking, cigarette smoking, and the risk of Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol 2002;52(3):276-284. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ana.10277]

14. Statistics South Africa. Mid-year Population Estimates 2011. Pretoria: SSA, 2011. http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022011.pdf (accessed 19 March 2012). [ Links ]

15. Heese JA. Die herkoms van die Afrikaner 1657 - 1867. Cape Town: AA Balkema, 1971. [ Links ]

16. Botha MC, Beighton P. Inherited disorders in the Afrikaner population of southern Africa. Part I. Historical and demographic background, cardiovascular, neurological, metabolic and intestinal conditions. S Afr Med J 1983;64(16):609-612. [ Links ]

17. Patterson N, Peterson DC, van der Ross RE, et al. Genetic structure of a unique admixed population: implications for medical research. Hum Mol Genet 2010;19(3):411-419. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddp505]

18. Van Den Eeden SK, Tanner CM, Bernstein AL, et al. Incidence of Parkinson's disease: variation by age, gender and race/ethnicity. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157(11):1015-1022. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwg068] [ Links ]

19. Twelves D, Perkins KS, Counsell C. Systematic review of incidence studies of Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 2003;18(1):19-31. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mds.10305] [ Links ]

20. Firestone JA, Smith-Weller T, Franklin G, et al. Pesticides and risk of Parkinson disease: a population-based case-control study. Arch Neurol 2005;62(1):91-95. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archneur.62.1.91] [ Links ]

Accepted 7 May 2012.

Corresponding authors:

Corresponding authors:

J Carr

(jcarr@sun.ac.za)

S Bardien

(sbardien@sun.ac.za)

Joint first authors: C van der Merwe and W Haylett