Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versión impresa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.101 no.11 Pretoria nov. 2011

ORIGINAL ARTICLES

Professionalism and the intimate examination - are chaperones the answer?

Ames DhaiI; Jillian GardnerII; Yolande GuidozziIII; Graham HowarthIV; Merryll VorsterV

IMB ChB, FCOG (SA), LLM, PG Dip Int Res Ethics. Steve Biko Centre for Bioethics, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

IIPhD candidate, MScMed (Bioethics & Health Law), BA. Steve Biko Centre for Bioethics, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

IIIBScNurs, LLB, MBA. Steve Biko Centre for Bioethics, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

IVMB BCh, MMed, FCPsych, PhD, BA. Steve Biko Centre for Bioethics, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

VMB ChB, MMed (O&G), MPhil (Bioethics) . Steve Biko Centre for Bioethics; Medical Protection Society, Leeds, UK

ABSTRACT

Complaints of sexual impropriety against health care practitioners are escalating. Professionalism in the practitioner-patient relationship and the role-based trust in health care do not allow crossing of sexual boundaries. Communication with patients is key to prevent erroneous allegations of sexual misconduct. The intimate examination is difficult to define. A chaperone present during an intimate examination protects the patient and practitioner and should be considered a risk reduction strategy in practice.

'In every house where I come I will enter only for the good of my patients, keeping myself far from all intentional ill-doing and all seduction and especially from the pleasure of love with women or men, be they free or slaves.' (from The Hippocratic Oath1)

The prohibition of sexual impropriety in the health practitioner-patient relationship dates back to the time of Hippocrates. Codifying the prohibition in the Hippocratic Oath underscored the vulnerability and highly exploitative situation of patients, the power of the practitioner and the importance of trust, in this unequal relationship. Nevertheless, increasing numbers of complaints of sexual misconduct are lodged against practitioners. At the HPCSA, the number of cases reaching the formal enquiry stage have also increased. The number of complaints lodged during the periods 2006/2007, 2007/2008 and 2009/2010 were 2, 5 and 28 respectively; 12 were finalised at the Preliminary Committees of Disciplinary Enquiry and did not reach a full formal enquiry, and 23 cases reached formal enquiry, with 13 practitioners found guilty. In a 5-year period (2005 - 2010), 22 practitioners were found guilty of sexual misconduct (9 in 2005 alone). Most of these were medical practitioners or psychologists.2 Such violations are not necessarily confined to physical actions; when a practitioner inappropriately uses words or actions of a sexual nature with a patient, a professional (sexual) boundary has been violated.

We draw attention to the importance of practitioners maintaining professional conduct in the context of intimate examinations, discuss the need for chaperones for the protection of the patient and the practitioner, and stress that adequate communication is essential to help prevent erroneous and false allegations.

Categories of sexual misconduct

Sexual misconduct may be categorised as:3 sexual impropriety - behaviour, gestures or expressions that are sexually suggestive, seductive or disrespectful of a patient's privacy or sexually demeaning to a patient; and sexual violation - physical sexual contact between a doctor and a patient, whether or not it was consensual and/or initiated by the patient. This includes any kind of genital contact or masturbation, and touching of any sexualised part of the body for purposes other than appropriate medically related examination or treatment. Exchange of prescriptions or other professional services for sexual favours is another example of a violation.

Defining an intimate examination

The intimate examination is not easy to define. Patients can easily misunderstand and misconstrue a legitimate clinical examination. The Medical Protection Society (MPS) defines intimate examinations as including, but not limited to, examination of the breasts, genitalia and rectum, and any examination where it is necessary to touch the patient in close proximity, e.g. conducting eye examinations in dim lighting. As most allegations of sexual assault against practitioners are due to inadvertent touching, the MPS cautions practitioners to be vigilant in situations of vulnerability, e.g. when listening to the chest, taking blood pressure using a cuff and palpating the apex beat, as these could involve touching the breast area.4

Trust and sexual relationships between practitioner and patient

Patients must be able to trust that the practitioner will work only for their welfare. Sexual involvement with a patient could affect the practitioner's medical judgment and thereby harm the patient. Sexual relationships between patients and practitioners are considered unethical and a form of professional misconduct by most professional councils, including the HPCSA. Because of the unequal power relationship and the dependence of the patient on the practitioner, even a consenting sexual relationship does not relieve the practitioner of its ethical prohibition. Hence, while sexual or romantic attraction between practitioner and patient may be 'normal', this does not override concerns over the disparity of power, vulnerability and the potential for exploitation and abuse that accompany such a sexual relationship. The existence of distinct professional principles for the ethical practice of medicine emphasises the distinct purpose and role of medicine in society.

The concepts of professionalism and trust also help to explain why, in medicine, 'disclosure and consent do not legitimize a practitioner's sexual involvement with a patient'.5 Society expects practitioners to refute a patient's invitation to an affair, as this oversteps the boundaries of their privileges and powers. Because they deliver crucial services to society, practitioners may ask probing questions and examine nakedness, i.e. invade privacy. The special privileges granted to practitioners carry the condition that they can be trusted to use these for the good of patients and society. This role-based trust in health care means that practitioners should practise according to science and the accepted ethical principles of medical practice, which include a non-sexual view of patients.

The health care profession is a social artefact created by giving control over a set of knowledge, skills, powers and privileges to a select few who are entrusted to provide their services in response to society's needs and to use their distinctive tools for the good of patients and society.5 Practitioners assume responsibility for the relationship and must act only in their patients' best interests. Allowing relationships to become sexualised can compromise their ability to fulfil their professional ability; because they are in the more powerful position, they must set and control the relationship boundaries.6

Chaperones in the context of intimate examinations

'Chaperone' is derived from the French word chaperon, initially meaning a hood and, later, a type of hat. In the 1700s, the English used the word 'chaperone' to refer to an escort, usually an accompanying older woman, to protect an unmarried younger woman's reputation in public.7 Over time, a new 'medical' category of chaperones appeared that is hotly debated, with diverging opinion as to its role and need.8 Studies show that practitioners generally see no need for chaperones during an intimate examination. They are viewed as obstructive during the consultation with patients, the latter becoming reluctant to make full disclosures in their presence; an intrusion on the practitioner-patient relationship; and a potential for breaching patient confidentiality. Patient preferences, on the other hand, are gender-based, with women preferring to have a chaperone present where the examiner is male.9

A chaperone could be necessary in certain situations to protect the practitioner-patient relationship. While some practitioners are guilty of boundary crossings and relationship violations, patients also sometimes falsely accuse their practitioners of sexual impropriety, including rape. Hence the presence of a chaperone would add that layer of protection to the practitioner that is necessary in current practice.8 According to the MPS, practitioners rarely receive allegations of sexual impropriety if a chaperone is present. A chaperone's presence also acknowledges the patient's vulnerability, and provides emotional comfort and reassurance; he/she could further assist the patient to undress, assist the practitioner during the examination, and act as an interpreter during the consultation.4

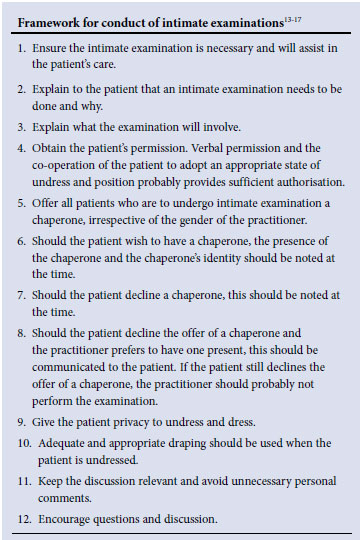

Professional bodies such as the General Medical Council, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists10 and the American Medical Association have long advised using a chaperone for intimate examinations. While chaperones primarily protect the patient, they also act as a risk management strategy for practitioners11,12 as the consequence of a false accusation can be devastating. However, in all cases, communication remains pivotal for the patient to understand the process of the examination and the reasons why certain questions must be asked and investigations done.

Chaperones, intimate examinations - legal issues

Legal issues concerning the practitioner-patient relationship and the need for a chaperone when performing an intimate examination are encompassed in the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences & Related Matters) Amendment Act 32 of 2007 ('the Act'). The Act defines sexual penetration as including any act which causes penetration to any extent whatsoever by inter alia any part of the body of one person, or any object into or beyond the genital organs or anus of another person. Sexual violation includes any act that causes direct or indirect contact between the genital organs or anus of one person, or a female's breasts, and any part of the body of another person, or any object, including any object resembling the genital organs. For these acts to be classified as crimes committed, the complainant must be able to prove beyond reasonable doubt that the perpetrator intended to behave in a sexual, and therefore inappropriate, way. The Act recognises that a complainant does not consent voluntarily or without coercion where the perpetrator abuses his/her power or authority to the extent that the complainant is inhibited from showing resistance or unwillingness to participate in the sexual act (s1(3)(b)). This includes a situation where the sexual act is committed under false pretences or fraudulently such as where the complainant is led to believe that the sexual act is something other than that act (for example, a medical examination). Rape is defined as the unlawful and intentional act of sexual penetration with a complainant who has not consented to it (s3), and sexual assault as the unlawful and intentional sexual violation of a complainant without consent (s5).

The main difference between an intimate examination and its potential to be labelled a crime is the practitioner's intention that the process is not meant to be sexual or sinister. A chaperone is able to verify this more easily than when no witnesses are present and the parties' versions are weighed against each other to establish the truth - which may be almost impossible in the absence of corroborating evidence.

The legal arguments against having a chaperone present may relate to the patient's right to privacy and the breach of confidentiality that could arise when a third person listens to the practitioner-patient conversation. All information about a user, including information about health status, treatment or hospital admission, is confidential unless the user consents in writing to having this information shared, there is a court order or law to justify it, or where non-disclosure would result in a serious risk to public health (National Health Act, 61 of 2003 s14). A chaperone is subject to the same limitations of s14 as a practitioner, and the patient would be in a position to act should a breach occur. However, it would be prudent to ask patients if they would like to have a chaperone present so that any objection can be timeously voiced. Where a chaperone is refused, it is advisable to document this in the patient's file and possibly ask the patient to sign it as acknowledgment of its truth. Where a chaperone is present, it would be prudent to record the name. The potential for the problem of a breach of confidentiality is also reduced by staff signing a confidentiality clause in their employment contracts so that there are serious consequences should confidentiality be violated.

Even if the practitioner's behaviour does not amount to a crime, the HPCSA recognises that there are instances where intimate medical examinations may lead to misunderstandings, and therefore require that practitioners always act in the patient's best interests, even if these conflict with their own interests, such as concern about a chaperone causing higher costs. Costs could be curbed by an assistant doubling up as a chaperone, which is applicable in the public and private sectors. While a patient may choose to have an accompanying person as a chaperone, practitioners are cautioned about the possibility of collusion between patient and chaperone in the instance of false allegations.

Conclusion

As allegations of sexual assault are increasing in South Africa, it is prudent to consider using chaperones during intimate examinations. While many practitioners may oppose this recommendation, using resource constraints as justification, they must recognise that chaperones serve also to protect the practitioner. Practitioners should not be falsely reassured where the patient is of the same gender. Other strategies to avoid complaints include allowing patients' privacy when they undress, and using drapes to maintain dignity. Adequate communication during the consultation as to why certain probing and sensitive questions are asked of the patient and why the particular examination is necessary can go a long way in avoiding complaints. Often the patient's failure to understand what the doctor was doing in the process of diagnosis and treatment is at the root of such allegations. At the least, all patients undergoing intimate examination should be offered a chaperone.

References

1. The Hippocratic Oath. In: Biomedical Ethics, 5th ed. Mappes TA, Degrazia D, eds. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2001:66. [ Links ]

2. Dhai A. Why do I need a chaperone? HPCSA: The Bulletin 2011:28-29. [ Links ]

3. Federation of State Medical Boards. Addressing Sexual Boundaries: Guidelines for State Medical Boards. 2006. http://www.fsmb.org.pdf/GRPOL_Sexual%20Boundaries (accessed 28 March 2011). [ Links ]

4. Medical Protection Society Fact Sheet. http://www.mps.org.uk (accessed February 2010). [ Links ]

5. Rhodes R. The Professional Responsibilities of Medicine. In: Rhodes R, Francis LP, Silvers A, eds. The Blackwell Guide to Medical Ethics. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing 2007:71-87. [ Links ]

6. RI Simon. 1995. The natural history of therapist sexual misconduct: Identification and prevention. Psychiatric Annals 25:90-93. [ Links ]

7. Tracy CS, Upshur REG. The medical chaperone: Outdated anachronism or modern necessity? Southern Medical Journal 2008;101(1):9-10. [ Links ]

8. Dhai A. To chaperone or not to chaperone? South African Journal of Bioethics and Law 2010;3(2):54. [ Links ]

9. Newton DC, Chen MY, Cummings R, Fairly CK. Recommendations for chaperoning in sexual health settings. Sexual Health 2007;4:207. [ Links ]

10. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Clinical Standards. Advice on Planning the Service in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2002. [ Links ]

11. Pydah KL, Howard J. The awareness and use of chaperones by patients in an English general practice. Journal of Medical Ethics 2010;36:512-513. [ Links ]

12. Suk Yook H, Yung Jang K, Lee H. Chaperone: For or against doctors. Yonsei Medical Journal 2009;50(4):599-600. [ Links ]

13. Ng DPK, Mayberry JF, McIntyre AS, Long RG. The practice of rectal examination. Postgrad Med J 1991;67:904-906. [ Links ] General Medical Council. Protecting patients, guiding doctors. London: GMC, 1996. [ Links ]

14. Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs, American Medical Association. Sexual misconduct in the practice of medicine. JAMA 1991;266:2741-2745. [ Links ]

15. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committtee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine. The use of chaperones during the physical examination of the pediatric patient. Pediatrics 1996;98:1202. [ Links ]

16. Croft M, Morrow, Randall S, Kishen M. Chaperones for genital examination. BMJ 1999;319:1266. [ Links ]

Accepted 13 June 2011.

Corresponding author: A Dhai (Amaboo.Dhai@wits.ac.za)