Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versão impressa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.101 no.11 Pretoria Nov. 2011

IZINDABA

Vital foreign-qualified doctors face xenophobia

Foreign doctors, the backbone of South African rural health care delivery, are being 'thrown in the deep end' with little support, supplementary training or supervision, resulting in serious miscommunication and sometimes even xenophobia from health care colleagues who treat them as professionally inferior.

This emerged during a discussion at the 15th annual conference of the Rural Doctors Association of Southern Africa (RuDASA), entitled 'Foreign qualified doctors; an essential and globally mobile resource - perspectives from healthcare workers and stakeholders in rural settings'. Held in the picturesque and historic mountain village of Rhodes in the Eastern Cape from 8 to 10 September, the conference attracted public sector doctors from across South Africa and neighbouring countries to focus on the theme 'Making primary health care better'.

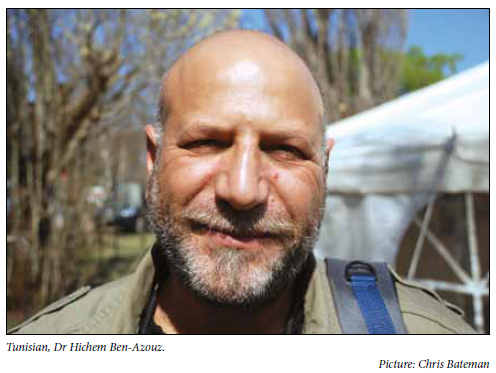

Tunisian Dr Hichem Ben-Azouz, stationed at Tintswalo District Hospital (Acornhoek) in Mpumalanga, said medicine was practised very differently in his (much smaller) home country, being highly specialised with 'a very easy' referral system - and doctors were trained accordingly, resulting in one of the best health indicators on the African continent. Back home, primary health care was 'totally covered, both in preventive and curative medicine', but he and many of his compatriots encountered major problems locally. A colleague told him that his medical manager (not well informed by the Department of Health about the foreign doctor workforce programme), believed that a doctor who could not do a C-section or give anaesthesia was 'totally useless'.

'I disagree,' says Ben-Azouz. Unlike Iranian doctors, who were not exposed to obstetrics and gynaecology in their country, Tunisians were trained in that specialty, but not allowed to do a C-section - identical to any other medical practitioner coming from France or many other European countries. 'In our health system only a specialist is allowed to have those skills'. He believes the responsible officials should have taken that into consideration at the outset with the country-to-country agreements and trained the Tunisians accordingly, placing them where their skills were the most appropriate. 'I had to sacrifice my family time and regularly travel 400 km to Nelspruit every weekend to learn how to do a C-section and anaesthesia. We were confronted here by very unfamiliar HIV, trauma and violence. In my curriculum HIV consisted of one paragraph,' Ben-Azouz said. He has up-skilled himself so well that he is now an honorary lecturer in HIV at Wits University and heads his hospital's HIV section, mentoring nurses and 5th-year medical students in the disease.

Exclusion 'shocking' for Tunisian

The genial French-speaking father of three, later told Izindaba that what shocked him most on his arrival (April 2008, along with 99 other Tunisians, as part of a government-to-government agreement), was the lack of moral and pragmatic support from some local colleagues. 'I was ready for the risk of violence and other problems, but not exclusion by colleagues whom we came to help out with the shortages. It's not an outright xenophobic attitude - more like ignoring you in a group speaking their own language or not informing, involving or supporting you. He qualified this, saying that when he moved to Tintswalo to work in HIV he was made to feel 'totally at home. Today my family and I are totally integrated and happy. But those who recruited us in Tunisia knew very well that no GP in our system is allowed to do C-sections or anaesthesia. So I think the South African government should have provided us with the proper training in those skills because we were willing to learn so we could help more efficiently. Being thrown into small isolated places where there is no support or supervision makes it hard to fit in.' These challenges led to 20% of his fellow Tunisians returning home early, among them vitally needed cardiologists, surgeons and urologists. 'They just couldn't handle it anymore,' revealed Ben-Azouz, whose wife teaches French at the local school. His experience of the national health department's Foreign Workforce Management Project (FWMP) was positive, in dramatic contrast to his management at provincial level. 'There was a coordinator at provincial level, who along with our embassy, was supposed to take care of us, but we hardly ever saw her,' he said. Ben-Azouz, whose English is excellent, cited a batch of compatriots who preceded him - posted around the Eastern Cape - who were given four months of initial supplementary local training, which led to their being 'very happy and effective'.

The Mpumalanga public sector would collapse without foreign doctors (80% are foreign qualified), yet little thought is given to geographically locating them where their individual skills can be put to best use - or to where there is adequate supervision and supplementary training.

'I feel when European doctors come to work in South Africa they are treated better by the local authorities. They are given more options for work according to their skills or preferences and don't face the same challenges we do - which is really unfair.'

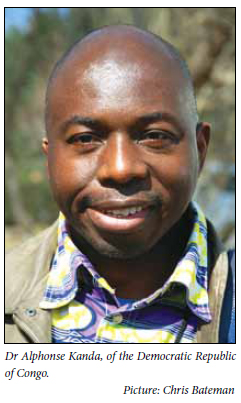

Discrimination 'structural' - DRC doctor

Dr Alphonse Kanda, of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), is a medical officer at the Polokwane-Mankweng (tertiary) Hospital Complex and has a postgraduate diploma in mental health.

After hearing Dr Bernhard Gaede, former principal medical officer at Emmaus Hospital in Winterton, KwaZulu-Natal, tell of how a xenophobic nurse-led campaign once resulted in the departure of most of his vital foreign-qualified doctors, Kanda, a political refugee, said his current biggest problem was fellow doctors, not the local community. 'Adjusting is very stressful - and when you have silence about an "us is better than them" attitude, plus difficulties in dealing with the higher authorities, it becomes very difficult,' he said, proposing a Southern African Development Community (SADC) support structure for doctors. Interviewed later by Izindaba, he said the xenophobia he experienced was totally unlike the recent crude headline-grabbing township violence. 'It's more structural, not clearly expressed - a bit like blue collar crime. For example, when you want to renew your three-year work or two-year refugee permits, there is an administrative delay, during which you don't get your salary for a month or two - so you can't pay your medical aid, debit orders lapse and so on. With the occupation specific dispensation (OSD) I have 20 years of postgraduate experience, but am pegged on Level Two (less than 10 years of experience). They say I'll be upgraded, but I'm still waiting.' Asked to give an example of collegial xenophobia, Kanda was anxious to avoid generalisations but cited an incident after he took a UNISA-based 'meaning-centred' counselling course. A local colleague wrote a letter of complaint to his supervisor and 'other higher officers' without ever directly approaching him, forcing him to respond to anonymous charges. When it came to this colleague, 'everything I'm writing or doing is wrong - because it comes from me,' he added. Administrators exercised discrimination by 'using the structures against you'. 'But it's important not to make out as if South Africans are ugly people. Many colleagues have been very helpful. We foreign doctors have our own evils. Everybody must be measured and assessed against their stated qualifications, otherwise it's just dangerous and unethical,' added Kanda, whose entire family fled ethnic violence in the DRC in 1994.

As if to illustrate bureaucratic dysfunction, just weeks after the RuDASA conference Ben-Azouz and his family came under threat of eviction from their officially allocated home, because the province had failed to pay the rent for four months.

Placement delays 'destructive' - veteran local

Gaede, a former chairperson of RuDASA and current Director of the Centre for Rural Health at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, said that during his 13 years at Emmaus Hospital (begun by his Germanborn grandmother), foreign doctors faced major bureaucratic, rotational and skillsmix challenges. Referring to the foreign doctor harassment incident he cited earlier, he said that 'once you have a hospital that doesn't want foreign-qualified doctors you might as well close it'. Inefficient bureaucracy meant that by the time a foreign doctor was seconded to your hospital, things had 'begun to fall apart'. 'It's the timing from when you are short-staffed to when a doctor comes in that can break a hospital completely. If nothing happens in a few months, things can fall to pieces. You need that light at the end of the tunnel to materialise - and there's a big expectation that the replacement doctor has to be able to do everything we can, though that's simply not true. Local doctors say it's not worth putting the effort in to get them. They forget that the foreign-qualified doctor also has certain expectations of working hours and scope of practice and it [the local reality] can be an absolutely frightening experience. I had one Tunisian doctor crying every night. She couldn't believe what was expected of her and told me, 'I'm a doctor ... but this!'

Gaede added, 'It's very difficult to manage - you have to compensate for somebody who is decompensating'.

Professor Ian Couper, director of the Wits Centre for Rural Health and Principal Specialist in Rural Medicine, North West Provincial Department of Health, echoed Gaede, saying that during his nine-year tenure at Manguzi Hospital (northern KwaZulu-Natal), new doctors were given a fortnight of orientation. 'When they come in with no other [experienced generalist] doctors there, it's a recipe for disaster. It's about managing people's expectations. No manager, clinical or otherwise, will take a foreign-qualified doctor over a South African if they have a choice - it's not xenophobic; our doctors are trained for our country,' he said.

Pragmatism dictates, not favouritism - top academic

When Dr Percy Mahlati, Director General of Human Resources in the national Department of Health, accused him of favouring foreign-qualified doctors, Couper's response was simple, 'give me a South African [trained] doctor and I'll take them!' He hit out at South Africa's so-called ethical policy of not recruiting health care professionals from Africa, while First-World countries found 'other ways around it', one outcome being that some African doctors ended up working as car guards locally. Citing the UK public health sector (signatory to an agreement on non-poaching from Africa), he said the UK's private sector continued recruiting hand-over-fist from Africa, 'and two weeks later the recruits move into the NHS'. The year after the UK signed the contentious agreement, it recruited twice as many foreign nurses as it had the previous year, he revealed.

'I think no doctors are worse than some doctors. And then, some foreign-qualified doctors I've examined at the Health Professions Council I wouldn't let near my cat,' he added. What was urgently needed was human resource managers who had the professional skills to assess CVs so that qualifications and experience were matched to positions. Additional support and advice were vital. He was echoed by Dr Karl le Roux, immediate outgoing chairperson of RuDASA, who said South African doctors needed to 'drop the arrogance' that all locally trained doctors were good and 'all foreigners' rubbish. Dr Richard Cook of the Wits University Rural Health Advocacy Project called for the scrapping of the 'limited skills' official terminology, urging for it to be changed to 'appropriate skills', saying a skills assessment should be a routine part of any foreign-qualified doctor's orientation. Dr Elma de Vries, a former deputy chairperson of RuDASA and senior lecturer in Family Medicine at the University of Cape Town, proposed mobile 'core teams' of competent doctors senior enough to train foreign and community service doctors and interns. Adding levity to the debate, Le Roux, a deep rural doctor and father of three, quoted a suggestion from a colleague wrestling with how to retain any doctors in rural areas: 'Just recruit doctor couples and sterilise them,' he quipped.

Chris Bateman

chrisb@hmpg.co.za