Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.101 n.10 Pretoria Oct. 2011

ORIGINAL ARTICLES

Family-witnessed resuscitation in emergency departments: doctors' attitudes and practices

E D GordonI; E KramerII; Ian CouperIII; P BrysiewiczIV

IMSc Med (Emergency Medicine). A&E Unit, Life Bedford Gardens Hospital; and Department of Emergency Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

IIMB BCh, BSc Hons, DipPEC (SA), FCEM (SA). Department of Emergency Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand

IIIBA, MB BCh, MFamMed, FCFP (SA). Department of Rural Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand

IVPhD. School of Nursing, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Resuscitation of patients occurs daily in emergency departments. Traditional practice entails family members remaining outside the resuscitation room.

OBJECTIVE: We explored the introduction of family-witnessed resuscitation (FWR) as it has been shown to allow closure for the family when resuscitation is unsuccessful and helps them to better understand the last moments of life.

RESULTS: Attending medical doctors have concerns about this practice, such as traumatisation of family members, increased pressure on the medical team, interference by the family, and potential medico-legal consequences. There was not complete acceptance of the practice of FWR among the sample group.

CONCLUSION: Short-course training such as postgraduate advanced life support and other continued professional development activities should have a positive effect on this practice. The more experienced doctors are and the longer they work in emergency medicine, the more comfortable they appear to be with the concept of FWR and therefore the more likely they are to allow it. Further study and course attendance by doctors has a positive influence on the practice of FWR.

Resuscitation of critically ill or injured patients occurs daily in emergency departments (EDs). Resuscitation involves the simultaneous integration of multiple tasks to save a critical patient's life, and may seem to be a frantic procedure for those not actively involved. Consequently, the medical team may request family members to wait outside the resuscitation room to isolate them from such events. The practice of family-witnessed resuscitation (FWR) has been explored since the late 1980s.1 FWR entails inviting a family member of the critical patient into the resuscitation room to witness the resuscitative process.2

The literature indicates that FWR assists final closure by family members in the event of unsuccessful resuscitation. Family members have an opportunity to witness the extent to which the medical team pursues the resuscitative attempt, to build up rapport with the medical team and to have questions answered immediately.

However, the opinions of medical and nursing staff regarding FWR vary.3-6 Common concerns include possible litigation, harassment by a family member during resuscitation, unnecessary prolonging of resuscitation owing to family presence, and psychological effects on family members.7

Work experience in the ED, the doctor's gender, and participation in emergency medicine continuing medical education courses were found to influence doctors' attitudes towards FWR.8-11 With more experience, doctors felt more comfortable about including family members during resuscitation of paediatric patients.11

The American Heart Association (AHA) published the need for family to be invited to witness cardiac pulmonary resuscitation of patients in their 2000 and 2005 Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiac Care.12 The AHA encourages family presence at the resuscitation, and recommends this in all AHA adult and paediatric life support courses.

Methods

We studied the attitudes of emergency doctors working in Gauteng hospital EDs towards FWR and whether they would consider implementing the practice. This was a cross-sectional descriptive study using a questionnaire based on themes from the literature review. Questions were both open- and closed-ended and included basic demographics, awareness of the practice of FWR, actual practice of FWR, consequences of allowing family to witness resuscitation, and the attitudes of doctors working in EDs towards FWR. Questions also ascertained whether participation in emergency medicine courses influenced the doctor's practice.

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences of the University of the Witwatersrand, and permission was obtained from the participating hospitals. The total study group canvassed comprised 101 doctors in 2 groups: those undertaking regular ED duties in various private EDs in Gauteng; and postgraduate candidates sitting for the part-time Master of Science in Medicine in Emergency Medicine (MScMed) degree in the Division of Emergency Medicine at the University of the Witwatersrand.

Anonymous questionnaires with a sealable envelope in which to return the completed form were distributed to the respondents. Collection boxes for the sealed envelopes were placed at each ED and outside lecture theatres. A total of 177 questionnaires were distributed, of which 101 were completed (57% response rate). Qualitative and quantitative data were analysed. Responses were tabulated and compared.

Results

Of the 101 respondents, 40 were female and 61 male; ages ranged from 26 to 59 years (mean 36.6 years). The average age of the women was 33.4 years and the men 38.1 years. Their ED experience varied from a few months to 30 years, with an average of 5 years; most had <10 years' experience.

Of the respondents, 80% were aware of FWR and 57% had previously allowed FWR; 72.5% of the women doctors and 47.5% of the males indicated that they would allow FWR. Older male doctors seemed more resistant to FWR as the average age of males not allowing FWR was 38.9 years compared with 37.4 years for those allowing it. Among female doctors, the relationship was reversed, with those not allowing FWR being younger; females allowing FWR were on average 34.3 years old, compared with 32.6 years for those not allowing FWR (Fig. 1).

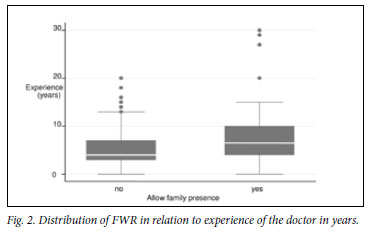

The Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann-Whitney) test shows that the probability of FWR increases with the experience of the doctor. Doctors indicating that they would consider FWR had worked in EDs for up to 30 years, while those who would not consider it fell within the category of 20 years of experience (Fig. 2).

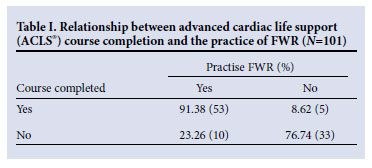

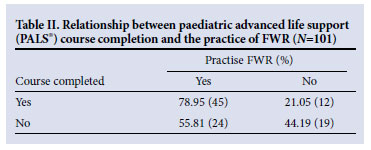

Postgraduate emergency medicine courses influenced respondents' attitudes and practices of FWR (Tables I - III).

Questioned as to which family members they would allow to witness resuscitation, doctors indicated that the parents and spouse or partner would preferentially be permitted. Asked whether they had received feedback from family members who had witnessed FWR, 86% of the replies were positive.

Doctors had several concerns regarding FWR: 72% expressed concern about possible traumatisation of a family member; 71% documented that FWR caused difficulty in terminating the resuscitation procedure; 60% felt that the cohesiveness of the medical team was affected by a family presence; 52% were afraid of personal intimidation; and 58% were concerned about patient privacy and of medico-legal complaints against themselves.

Comments to the open-ended questions include: The doctor's personality would affect the manner in which the resuscitation was conducted; The nature of the resuscitation, be it medical or trauma, would influence a doctor's decision to allow family to witness the resuscitation; To assist the family in understanding the resuscitation process, adequate staff were needed in the resuscitation room; and Sufficient space is important to allow the family to view proceedings without hindering the medical team in performing their duties.

Discussion

Since Doyle at the Foote Hospital allowed family to witness the resuscitation of family members in the 1980s,1 the positive feedback from those who had participated in such an experience spurred further enquiry into FWR.13 Of doctors who completed the questionnaire, 42.6% had never considered FWR. However, 65% of them indicated that, having been made aware of FWR, they would positively consider it in future. Consequently, once doctors and nursing staff were introduced to the concept of FWR during the interviews, they were more willing to consider allowing it.

Experienced doctors with a thorough understanding of the process of resuscitation are more comfortable with FWR. However, experience in an ED is not synonymous with a doctor's age, as some graduate and start practising in EDs immediately, while others do so at a later stage.

Arguments against FWR are based on several universal concerns and are repeatedly quoted in the literature.2,3,14,15,16 We found the concerns to be cohesiveness of the medical team and performance anxiety of the doctors, particularly if sensing that their performance were being critically assessed by an attending family member who might have medical knowledge and experience. Additional concerns included: feeling compelled to prolong resuscitation when family present, and not to be seen to be making decisions too rapidly; traumatisation of family members; potential medico-legal action;3,15,16 and space and staffing limitations. Litigation was uncommon in EDs in the UK, where the practice of FWR is common.16 The lack of adequate space in the resuscitation room is a concern.8 Additional staff should be available for the family to explain procedures, answer their questions, ensure that they do not interfere or become inappropriately affected by the resuscitation process and procedures that may require their removal from the resuscitation room.

Doctors' training appears to influence their acceptance of FWR. We found that 91.3% of doctors who had completed an American Heart Association's Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support (AHA ACLS®) course, and 79% of doctors who had completed an AHA Pediatric Advanced Life Support (AHA PALS®) course, would allow FWR. These courses promote FWR and include FWR in practice scenarios, and doctors participating in them become aware of FWR and experience-simulated scenarios. Familiarity with FWR seems to encourage its practice (Tables I and II). Even having attended an Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS®) course influenced the practice of FWR as 84% of doctors who had attended an ATLS course practise FWR (Table III). Although FWR is not taught in ATLS courses, doctors presumably gain confidence in resuscitation skills during this course that conduces them to FWR. Educational programmes and training facilitate the practice of FWR.17 We did not investigate the influence of other courses on the practice of FWR, which could be the basis of another research report.

Successful implementation of FWR in EDs in South Africa would encourage organisations such as the Emergency Medicine Society of South Africa, Emergency Nursing Society of South Africa and the Resuscitation Council of South Africa to produce protocols for the introduction and implementation of FWR. Training programmes must be developed for undergraduate and postgraduate medical training, and policies and procedures developed to allow the regular practice of FWR in all EDs.

References

1. Guzzetta CE, Clark AP, Wright JL. Family presence in emergency medical services for children. Clin Paed Emerg Med 2006;1(2):15-23. [ Links ]

2. Goodenough TJ, Brysiewicz P. Witnessed resuscitation - exploring the attitudes and practices of emergency staff working in level 1 Emergency Departments in the province of KwaZulu-Natal. Curationis 2003;26:56-63. [ Links ]

3. Kissoon N. Family presence during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: Our anxiety versus their needs. Paed Crit Care Med 2006;7(5):488-489. [ Links ]

4. McClenathan BM, Torrington KG, Uyehara CFT. Family member presence during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A survey of US and International Critical Care Professionals. Chest 2002; 22:2204-2211. [ Links ]

5. Gold KJ, Gorenflo DW. Physician experience with the family presence during CPR in children. Paed Crit Care Med 2006;7(5):428-433. [ Links ]

6. Macy C, Lampe E, O' Neil B, Swor R, Zalenski R, Compton S. The relationship between the hospital setting and perceptions of family-witnessed resuscitation in the emergency department. Resuscitation 2006;70:74-79. [ Links ]

7. Davidson JE. Family presence at resuscitation: What if? Critical Care Medicine 2006;34(12):3041-3042. [ Links ]

8. Walker W. Accident and emergency staff opinion on the effects of family presence during adult resuscitation: critical literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2008;61(4):348-362. [ Links ]

9. Engel K, Barnosky AR, Berry-Bovia M, Desmond JS, Ubel PA. Provider experience and attitudes toward Family Presence during Resuscitation Procedures. J Palliat Med 2007;10(5):1007-1009. [ Links ]

10. Mazar MA, Cox LA, Capon JA. The public's attitude and perception concerning witnessed cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Crit Care Med 2006;34(12): 2925-2928. [ Links ]

11. Barata I, LaMantia J, Riccardi D, et al. A prospective study of emergency medicine residents' attitudes towards family presence during paediatric procedures. The Internet Journal of Emergency Medicine 2007;3(2). http://www.ispub.com/ostia/index.php?xmlFilePath (accessed 17 August 2008). [ Links ]®

12. American Heart Association. AHA 2005 guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency care. Circulation 2005;112(suppl): IVI-203. [ Links ]

13. Salmond SW, Palpanus LM. A comprehensive systematic review of Family Witnessed Resuscitation and Family Witnessed invasive procedures in adults in hospital settings internationally. http://www.joannabriggs.edu.au/pubs/systematic_reviews_prot.php (accessed 19 January 2010). [ Links ]

14. Isaacs A, Mash RJ. An unsuccessful resuscitation: The families' and doctors' experiences of an unexpected death of a patient. SA Fam Pract 2004;46(8):20-25. [ Links ]

15. Maurice H. Family presence in Emergency Department resuscitation: A proposed guideline for an Australian hospital. Australian Emergency Nursing Journal 2002;5(3): 21-27. [ Links ]

16. Booth MG, Woolrich L, Kinsella J. Family witnessed resuscitation in UK emergency departments: a survey of practice. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2004;21:725-728. [ Links ]

17. Critchell CD, Marik PE. Should family members be present during cardiopulmonary resuscitation? A review of the literature. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine 2007;24(4):311-317. [ Links ]

Accepted 16 May 2011.

Corresponding author: E Gordon (eviedoc@mweb.co.za)