Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.101 n.10 Pretoria Oct. 2011

IZINDABA

Vasbyt now, reap NHI dividends later - Green Paper

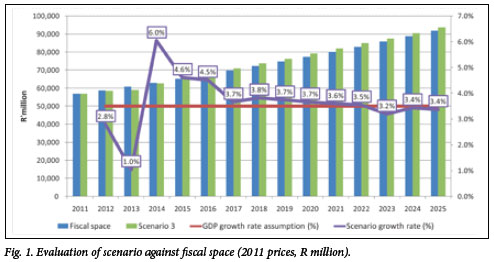

While the National Health Insurance (NHI) will require an increase in health care spending that initially outstrips even projected GDP increases, the level of spending relative to GDP in 14 years' time (6.2%) will be less than the current total health care spending of 8.5% of the GDP (Fig. 1).

This is according to preliminary cost estimates in the government's Green Paper released last month after exhaustive research of similar models world wide and dynamic, ongoing consultation with National Treasury.1 Treasury projects a modest real GDP growth from the existing 3.1% to 3.6% in 2011/2012 and 4.2% in 2012/2013 -providing cold comfort for the initial launch of the most ambitious re-engineering of the South African health system ever attempted.

Firming up existing expert opinion that mandatory NHI contributions above a yet-tobe-specified income threshold will probably result in forced migration of the middle classes out of medical aids onto the NHI, the Paper argues that initial spending on the NHI will be offset 'by the likely decline in spending on medical schemes'. Using 2005/2006 Income and Expenditure Survey data, it points to the overall average level of contributions for all medical scheme members as standing at just over 9% of their income. The survey finds the lowest income medical aid members (comprising 40% of total membership) contribute 14% of their income, the middle (comprising 20% of members) nearly 12%, while the wealthiest (20% of members) fork out 5.5% of their income. How much an NHI mandatory contribution would 'add' to this (speculation centres on 5 - 6%), is set to create a storm of public debate when it is tabled. Proponents will almost certainly cite the benefits for the 84% of South Africans with no medical aid for whom any out-of-pocket expenses could have 'catastrophic' financial effects, as far outweighing the extra burden on existing medical aid members (financial or service quality).

The Green Paper's intention is that the NHI benefits, to which all South Africans will be entitled, will be 'of sufficient range and quality' that everyone will have a real choice as to whether to continue medical scheme membership or simply draw on their NHI entitlements.

Patient benefit provider - real or forced choice?

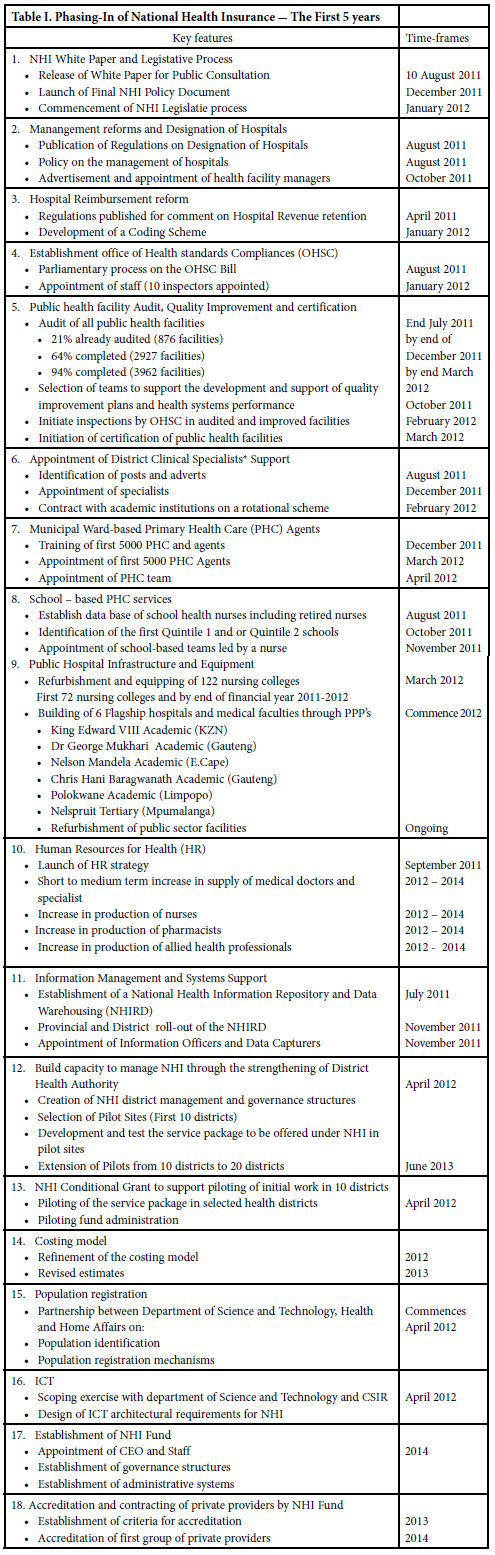

Whether that 'real choice' transpires will depend on the outcome of the first of three phases in a 14-year NHI implementation time-line. The first five 'building block' years will be dedicated to what the Paper terms 'drastic improvement' of infrastructure, patient treatment, human resources, management and information systems and quality control (Table I). It warns pragmatically that 'no amount of funding' will ensure the sustainability of an NHI unless existing systemic challenges within the health system are addressed.

The jacking up of the health system will be piloted in 10 sites from next year, with Health Minister, Dr Aaron Motsoaledi, revealing that they would be chosen from a mix of richer and poorer districts 'so we can ensure we get it right'. The Office of Healthcare Standards Compliance has already audited 29% of public health facilities and aims to have 94% done by the end of March. Norms and standards will be set and health providers monitored by a special office set up by Parliament. Patients will be able to report poor treatment to an ombudsman. Motsoaledi said the choice of pilot sites would depend on the health status of the district and the management of institutions and transport systems.

Primary health care (PHC) will be delivered at a district level via the following:

District-based specialist teams providing clinical support and oversight, especially in those districts with high disease burdens. Aimed primarily at the embarrassingly high levels of maternal and child mortality, they will consist of a principal obstetrician and gynaecologist, a principal paediatrician, a principal family physician, a principal anaesthetist, a principal midwife and a principal primary health care professional nurse - with others added over time as the need arises.

• School-based services which will deal with immunisation, parasites, child abuse, school readiness, sexual health and nutrition.

• Municipal ward-based PHC 'agents' (at least 10 per ward) will be allocated a certain number of families to monitor their health and encourage community involvement in promoting healthy behaviour. (There are over 4 000 wards in the country.)

• Accredited and contracted private providers practising within a district. Government will specify the range of services to be provided by private providers, including GPs, with the aim of ensuring that patients 'don't have to travel long distances for care'. These private providers will be compensated via the NHI fund, but details of how still need working out. All the document says is that accredited PHC providers will be reimbursed 'using a risk-adjusted capitation system linked to a performance-based mechanism'. Annual payment will be linked to the size of the district's population, disease profile, level of use and costs.

Done properly, NHI will save thousands of lives

The Green Paper says that 'Properly delivered through the primary health care streams, this [district] package could eliminate 21% to 38% of the burden of premature mortality and disability in children under 15 years of age, and 10% to 18% of the burden in adults'. The objectives of the unprecedented district clinical specialist support teams will be not only to promote innovative models of specialist health care closer to the patients' home, but to advance integrated working practices between GPs and hospital-based specialists, improve service quality at the first level of care (by ensuring proper treatment protocols) and provide peer support for specialists already working in primary care. The Paper stresses: 'These are not outreach specialists, but an integral and permanent feature' of the new landscape.

Hospitals in South Africa will be re-designated as district, regional, tertiary, central and specialised. District hospitals will provide general medical services in four basic areas: maternity and gynaecological services, child health, general surgery and family medicine. They will also deal with trauma and emergency care, in-patient care, out-patient visits, rehabilitation services, geriatric care, and laboratory and diagnostic services. Aside from the four services offered by district hospitals, regional hospitals will provide orthopaedics, psychiatry, radiology and anaesthetics. They will receive referrals from district hospitals and provide specialist services to a number of district hospitals (preferably six or less). Tertiary hospitals will provide specialist services including cardiology, craniofacial surgery, diagnostic radiology, ear, nose and throat (ENT), endocrinology, geriatrics, haematology, human genetics, infectious diseases, as well as the other eight services offered by regional hospitals. They will also train.

Central hospitals are national referral hospitals attached to a medical school and provide a training platform for the training of health professionals and research. Specialised hospitals are usually one-discipline focused (e.g. tuberculosis or psychiatry). Private hospitals will also be contracted to deliver health services to all, and will be paid 'using global budgets with a gradual migration towards diagnosis related groups with a strong emphasis on performance management'. Government was still developing 'mechanisms for achieving cost-efficiency' in contracting private providers.

Per capita health spending 'grossly skewed'

In its underpinning motivation, the Green Paper cites the comparative per capita annual expenditure for a person on medical aid as R11 150 compared with expenditure on a public sector dependant person of R2 766 annually, commenting, 'This is not an efficient way to fund health care'. Overpricing had led to a dramatic decline in medical schemes from 180 in 2001 to 102 just eight years later. It cited the World Health Organization (WHO)'s 2008 report on three trends that undermined improvement of health care outcomes globally: hospital centrism with a strong curative focus, a fragmentation in approach which may be related to programmes or service delivery and 'uncontrolled commercialism which undermines the principles of health as a public good'.

The paper defined uncontrolled commercialism as the practice that 'turns goods and services into products for the sole purpose of generating profits'. It quoted UN Secretary General Ban-Ki Moon at the 2009 UN General Assembly (on 'Advancing global health in the face of crisis') as saying: 'There is a cohesive, compelling ethical and pragmatic argument for an NHI. Investment to scale up basic health services can bring about a six-fold economic return, improved life expectancy, school attendance and generate a more productive populace with lower birth rates, thus investing more in fewer children.'

In other middle-income countries where an NHI was implemented, each extra year of life expectancy raised a country's GDP per person 'by about 4% in the long run,' the Green Paper said.

Chris Bateman

chrisb@hmpg.co.za

1. Government Gazette, Republic of South Africa, 12 August 2011; 554: No. 34523.st. [ Links ]