Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.101 n.9 Pretoria Sep. 2011

ORIGINAL ARTICLES

Dual and triple therapy to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV in a resource-limited setting-lessons from a South African programme

Rosemary GeddesI; Janet GiddyIII; Lisa M ButlerV; Erika van WykIV; Tamaryn CrankshawV; Tonya M EsterhuizenVII; Stephen KnightII

IMB ChB, MMed (PHM), FCPHM (SA). Department of Public Health Medicine, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban

IIMB BCh, FCPHM (SA). Department of Public Health Medicine, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban

IIIMB ChB, Dip PHC Ed, MFamMed. McCord Hospital, Durban

IVMB ChB, DCOG. McCord Hospital, Durban

VPhD, MA. McCord Hospital, Durban

VIPhD, MPH. Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, and Global Health Sciences, University of California, San Francisco, USA

VIIMSc. College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE: To determine outcomes of pregnant women and their infants at McCord Hospital in Durban, South Africa, where dual and triple therapy to reduce HIV vertical transmission have been used since 2004 despite national guidelines recommending simpler regimens.

METHOD: We retrospectively examined records of all pregnant women attending McCord Hospital for their first antenatal visit between 1 March 2004 and 28 February 2007. Uptake of HIV testing and HIV prevalence were determined, and clinical, immunological and virological outcomes of HIV-positive women and their infants, followed through to 6 months after delivery, were described.

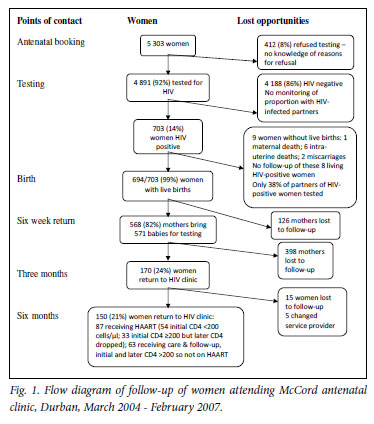

RESULTS: The antenatal clinic was attended by 5 303 women; 4 891 (92%) had an HIV test, and 703 (14%) were HIV positive. The HIV-positive women were subsequently followed up: 653 (93%) received antiretroviral therapy or prophylaxis, including 424 (60%) who received triple therapy. Of the 699 live babies delivered, 661 (94%) received prophylaxis. At 6 weeks 571 babies (82%) were brought back for HIV testing; 16 (2.8%) were HIV positive. After 6 months, only 150 women (21%) were receiving follow-up care at the adult HIV clinic.

CONCLUSION: Where a tailored approach to prevention of motherto- child transmission (PMTCT) is used, which attempts to maximise available technology and resources, good short-term transmission outcomes can be achieved. However, longer-term follow-up of mothers' and babies' health presents a challenge. Successful strategies to link women to ongoing care are crucial to sustain the gains of PMTCT programmes.

In 2009 there were an estimated 2.5 million children under the age of 15 years living with HIV worldwide, and 370 000 new infections in children, the vast majority due to mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) in sub-Saharan Africa.1 Without intervention, MTCT of HIV is 25 - 45%.2 Effective counselling and testing, access to antiretroviral therapy, and safe delivery and infant feeding practices have virtually eliminated MTCT in high-income countries.

In South Africa in 2009, 29.4% of women aged 15 - 49 years attending public health clinics for antenatal care were HIV positive.3 Although child mortality is falling worldwide, in South Africa it has risen,4 and HIV is responsible for 40% of deaths, thereby constituting the leading cause of under-5 mortality.5 Roll-out and progress of prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT) services, commenced almost a decade ago in South Africa, has been slow.6,7

PMTCT programmes offer a unique opportunity for health services to provide comprehensive treatment and care; engage with women living with HIV, their infants and their partners; and establish relationships that could improve their long-term survival. Despite concerns about subsequent drug resistance,8,9 PMTCT services in the public sector in South Africa, as in many resource-constrained countries, offered a single dose of nevirapine to the mother and her infant at delivery, until early 2008 when dual therapy (zidovudine during pregnancy and nevirapine at delivery) was introduced. Previously we described the results of the first 18 months of a South African PMTCT programme in which dual and triple therapy have been used since 2004.10 We now report on outcomes achieved and lessons learned in the programme after 3 years.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study design was used to describe maternal and child health outcomes of women who received PMTCT care between March 2004 and February 2007 at McCord Hospital, a state-aided general hospital in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal (KZN). This PMTCT service was supported by the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation and the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). It is integrated with routine antenatal care, and serves a diverse catchment population. Whereas antenatal HIV seroprevalence in the KZN public sector was almost 40%,3 at McCord it was 14%. During the study period, patients were charged a subsidised user fee of R140 (~$19.26 in 2005 US dollars) for each antenatal visit, which included comprehensive PMTCT care. 'Optout testing' was adopted in August 2006 using the CDC definition11 where information regarding a batch of recommended antenatal tests is conveyed during a group session and patients are able to opt out of any tests. Postnatally, mothers were referred for follow-up at the HIV clinic, where the inclusive cost was R160 per visit. Threemonthly visits were required for women continuing on triple therapy (highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART)) and 6-monthly visits for those who received antiretrovirals for PMTCT only. HIV-positive babies were followed up at the same HIV clinic, while negative babies were referred to government immunisation clinics after the 6-week polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test and result.

The PMTCT treatment options at McCord were influenced by international best practice and evidence12 and did not follow the public sector guidelines, which at the time recommended single-dose nevirapine at birth for women with CD4 counts >200 cells/µl. Over the study period, McCord PMTCT programme clinical guidelines evolved as evidence emerged, drugs became more available, and funding for dual and triple therapy was secured. The choice of regimen for individual women was determined by CD4 count, viral load, prior use of antiretroviral therapy, cost factors and the gestational age at which women presented for antenatal care (Table I). Initially a caesarean section was offered to all women to reduce intrapartum HIV transmission. By mid-2005, a routine viral load test at 36 weeks enabled a policy of recommending vaginal delivery (if there was no obstetric indication for caesarean section) in women with a viral load <1 000 copies/ml. All infants were to be given a single dose of nevirapine within 72 hours of birth and zidovudine for 1 week.

Records of all pregnant women attending McCord Hospital for their first antenatal visit between 1 March 2004 and 28 February 2007 were examined to determine uptake of HIV testing and HIV prevalence. Clinical, immunological and virological outcomes of HIV-positive women and their infants were followed up to 6 months after delivery. Data were analysed using SPSS 15 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill). To determine associations between maternal characteristics and loss to follow-up at 6 weeks, we conducted bivariate analysis using chi-square tests. Chi-square for trend was used to identify change in regimen and delivery methods over time. Two-tailed p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The study was approved by the University of KwaZulu-Natal Biomedical Research Ethics Committee and the McCord Hospital Research Ethics Committee.

Results

During the 3-year period, 5 303 women attended the McCord Hospital antenatal clinic; all received counselling, and 92% (N=4 891) accepted HIV testing (Fig. 1). Of the tested women 703 (14%) were HIV positive, and 266 (38%) of their partners were tested at McCord Hospital of whom 182 (68%) were HIV positive.

Of the 703 HIV-positive women, 653 (93%) received antiretroviral therapy; of these, 424 (60%) received triple therapy (Tables II and III). From programme year 1 to year 3 the use of triple therapy increased from 39% to 71% (χ2trend=48.7, p<0.001), while single-dose nevirapine prophylaxis decreased from 32% to 11% (χ2trend=34.9, p<0.001) (Table II). Dual therapy declined from 23% in year 1 to 8% in year 2 and 10% in year 3. Baseline CD4 counts were performed before antiretroviral initiation in 642 (91%) of the HIV-positive cohort, of whom 146 (23%) had CD4 counts <200 cells/µl (Table II). Of these 146 HAART-eligible women, 122 (84%) were commenced on HAART for life.

Among the 703 HIV-positive women, 700 delivered; of these, 694 delivered live infants, including 5 pairs of twins (Table II). Of the 680 births for which the delivery method was documented, 427 (63%) were by caesarean section. There was a significant reduction in the proportion of deliveries by caesarean section from 74% (154/208) in year 1 to 57% (119/210) in year 2 and 59% (154/262) in year 3 (χ2trend=9.6, p=0.002).

After delivery, 661 of the 699 (95%) babies received antiretroviral prophylaxis: 585 (89%) received a single dose of nevirapine and 1 week of zidovudine, 68 (10%) received nevirapine only, and 8 (1%) received prophylaxis but the regimen was not specified. In 38 babies (5%) no prophylaxis was recorded.

At 6 weeks 571 (82%) of the babies returned for HIV testing by PCR, and 16 (2.8%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.7 -4.6%) were found to be HIV positive. Bivariate analysis found no statistically significant association between potential maternal risk factors (including age, marital status, gestation at first visit, CD4 counts and delivery method) and loss to follow-up at 6 weeks. Of the 694 HIVpositive women with live births, 524 (76%) were lost to follow-up 3 months after delivery. After 6 months, of 700 women who delivered only 150 (21%) were receiving ongoing care at the McCord Hospital general HIV clinic, including only 54 (37%) of the 146 women who were initially eligible for HAART for life (Fig. 1).

Discussion

We examined a PMTCT programme in a high HIV prevalence setting in sub-Saharan Africa, which used dual and triple therapy and opt-out testing. Of the women presenting for antenatal care, 92% were tested for HIV and overall HIV transmission occurred in less than 3% of babies tested 6 weeks after delivery. This is in sharp contrast to transmission rates in KZN public sector clinics at the time, where an estimated 20.8% (95% CI 18.2 - 23.6) of 6-week-old infants born to HIV-positive pregnant women, where only single-dose nevirapine was utilised, were found to be infected.13 Of HAART-eligible women, 84% were commenced on HAART, compared with only 51% in a 2010 study from Cape Town.14 However, of those women identified as HIV positive, only 21% were attending the general HIV clinic 6 months later. At McCord Hospital, access (financial and geographical) and the stigma of follow-up at the 'HIV clinic' may in part have been responsible for this drop-off. Longer-term follow-up is important to encourage mothers to engage with services and stay healthy and adherent to medication, thereby improving their own and their infants' chances of survival. This is recognised as a challenge to PMTCT providers.15

The retrospective nature of the study may have led to information and selection bias. Specifically, the 18% loss to follow-up of babies 6 weeks after delivery may have led us to underestimate transmission. Although unlikely, if all 128 infants who did not return at 6 weeks were infected, transmission may have been as high as 20.6% (95% CI 17.6 23.6). Poor retention following delivery also compromised our ability to accurately determine the HIV transmission to infants by 6 months of age and to assess other maternal and child health outcomes.

Because of the user fee, patients attending McCord Hospital are likely to be socio-economically and educationally better off than those attending public facilities. This may influence general health and adherence to medication and results may therefore not be generalisable to the broad antenatal population of South Africa, limiting the external validity of the study.

Triple therapy for PMTCT is feasible in the sub-Saharan setting, but implementation requires sufficient resources for staff, their training, and the availability of basic laboratory technology and drugs. A goal of the South African National Strategic Plan for HIV/ AIDS and Sexually Transmitted Infections 2007 - 201116 is to reduce MTCT of HIV to less than 5%. Results of operational research at sites using dual therapy suggest that it is unlikely that vertical transmission of less than 5 - 9% will be achieved.17,18 This study demonstrates that the appropriate use of available resources can achieve good outcomes; in particular, the use of CD4 counts and viral loads in this programme allowed tailored prophylactic regimens and a reduced caesarean section rate. Focusing solely on short-term MTCT of HIV, however, is insufficient and results in lost opportunities. Outcomes such as 6-month and 1-year HIV-free infant survival should become standard indicators. The importance of longer-term follow-up must be emphasised, and successful strategies to link women to ongoing care are crucial to sustain the gains of PMTCT programmes.

Acknowledgement. We are grateful to Professor George Rutherford, University of California, San Francisco, for commenting on the manuscript, and Sandy Reid, Candace Westgate, Hiliary Plioplys, Kristy Nixon, Chantelle Young, Terusha Chetty, Jamie Cohen and James Hudspeth for their assistance with data collection.

References

1. UNAIDS. Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic, 2010. Geneva: UNAIDS, 2010. [ Links ]

2. Working Group on MTCT of HIV. Rates of mother-to-child transmissionof HIV-1 in Africa, America and Europe: results of 13 perinatal studies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 1995;8:506-510. [ Links ]

3. Department of Health. National HIV and Syphilis Antenatal Sero-prevalence Survey South Africa 2009. Pretoria: National Department of Health, 2010. [ Links ]

4. Bradshaw D, Chopra M, Kerber K, et al. Every death counts: use of mortality audit data for decision making to save the lives of mothers, babies, and children in South Africa. Lancet 2008;371:1294-304. [ Links ]

5. Bradshaw D, Bourne D, Nannan N. What are the Leading Causes of Death among South African Children? Cape Town: Medical Research Council of South Africa, 2003. [ Links ]

6. UNICEF. Monitoring Progress on the Implementation of Programs to Prevent Mother to Child Transmission of HIV. PMTCT Reportcard, 2005. New York: UNICEF, 2005. [ Links ]

7. WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF. Towards Universal Access: Scaling Up Priority HIV/AIDS Interventions in the Health Sector. Progress Report, 2007. Geneva: WHO, 2007. [ Links ]

8. Jourdain G, Ngo-Giang-Huong N, Le Coeur S, et al. Intrapartum exposure to nevirapine and subsequent maternal responses to nevirapine-based antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 20045;351(3):229-240. [ Links ]

9. Lockman S, Shapiro RL, Smeaton LM, et al. Response to antiretroviral therapy after a single, peripartum dose of nevirapine. N Engl J Med 2007;356(2):135-147. [ Links ]

10. Geddes R, Knight S, Reid S, Giddy J, Esterhuizen T, Roberts C. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV programme: low vertical transmission in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. S Afr Med J 2008;98(6):458-462. [ Links ]

11. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55(RR-14):1-17. [ Links ]

12. World Health Organization. Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating Pregnant Women and Preventing HIV Infection in Infants. Geneva: WHO, 2004. [ Links ]

13. Rollins N, Mzolo S, Little K, Horwood C, Newell ML. Surveillance of mother-to-child transmission prevention programmes at immunization clinics: the case for universal screening. AIDS 2007;21(10):1341-1347. [ Links ]

14. Stinson K, Boulle A, Coetzee D, Abrams EJ, Myer L. Initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy among pregnant women in Cape Town, South Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2010;15(7):825-32. [ Links ]

15. Nassali M, Nakanjako D, Kyabayinze D, Beyeza J, Okoth A, Mutyaba T. Access to HIV/AIDS care for mothers and children in sub-Saharan Africa: adherence to the postnatal PMTCT program. AIDS Care 2009;21(9):1124-1131. [ Links ]

16. South African National AIDS Council. HIV & AIDS and STI National Strategic Plan 2007 - 2011. Pretoria: Department of Health, 2007. [ Links ]

17. Coetzee D, Hilderbrand K, Boulle A, et al. Effectiveness of the first district-wide programme for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in South Africa. Bull World Health Organ 2005;83(7):489-494. [ Links ]

18. Draper B, Abdullah F. A review of the mother-to-child prevention of transmission programme of the Western Cape provincial government, 2003-2004. S Afr Med J 2008;98(6):431-434. [ Links ]

Accepted 19 May 2011.

Corresponding author: R Geddes (rosemary.geddes@hgu.mrc.ac.uk)