Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.101 n.8 Pretoria Aug. 2011

ORIGINAL ARTICLES

More doctors and dentists are needed in South Africa

B StrachanI; T ZabowII; Z M van der SpuyIII

IBSc Hons, MA, PhD, MSc. Colleges of Medicine of South Africa, Cape Town

IIMB ChB, DPM, FCPsych (SA), MRCPsych (UK). Colleges of Medicine of South Africa, Cape Town

IIIPhD, MB ChB, FRCOG, FCOG (SA). Immediate Past President of Colleges of Medicine of South Africa; Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Cape Town

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: An aim of the Colleges of Medicine of South Africa (CMSA) project 'Strengthening Academic Medicine and Specialist Training' was to research the number and needs of specialists and subspecialists within South Africa.

METHODS: Data were collected from several sources: Deans of the 8 Faculties of Health Sciences and the Presidents of the 27 constituent Colleges of the CMSA completed a survey; and the HPCSA's Register of Approved Registrar Posts for Faculties of Health Sciences was examined and the results tabulated.

RESULTS: South Africa compares unfavourably with middleincome countries on the ratios of medical and dental professionals; many districts have limited access to specialists and subspecialists. The unacceptable ratio of doctors, dentists and other health professionals per capita needs to be remedied, given South Africa's impressive reputation for its output of health professionals, including the areas of medical training, clinical practice and clinical research. The existing output from South Africa's 8 medical schools of MB ChB and specialist graduates is not being absorbed into the public health system, and neither are other health professionals.

CONCLUSION: Dynamic leadership and policy interventions are required to advocate and finance the planned increase of medical, dental and other health professionals in South Africa.

In 2008, the Colleges of Medicine of South Africa (CMSA) initiated a project entitled 'Strengthening Academic Medicine and Specialist Training' as a response to the concern among medical and dental professionals about increasing challenges in the academic training environment and issues relating to the output and retention of specialists and sub-specialists in the public health services. These challenges significantly affect the capacity of the public and private health sectors to provide South Africa's required quality of health care and to ensure the output of sufficient health professionals to meet its needs.

A prime aim of the CMSA project was to research the need for, and numbers of, specialists and subspecialists within South Africa; this is ongoing, and the initial results are presented herein.

Objectives

The objectives of the CMSA project were to:

• compare South Africa internationally regarding the number of doctors and dentists per 1 000 population

• establish the number of specialists and subspecialists in South Africa

• establish whether these numbers meet South Africa's healthcare requirements

• identify the cost of registrar training should finances be needed to increase the output

• develop an Excel model and database to capture and monitor data on specialists and subspecialists by discipline and Faculty.

Methods

Data were collected from the following sources:

• World Health Organization (WHO) country data on medical doctors and dental personnel.

• Public and private sources of data in South Africa on health professionals included the National Department of Health (DOH), CMSA, National Treasury, Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA), a large private funder, Board of Healthcare Funders (BHF), South African Medical Association (SAMA) and Medpages.

• The deans of the eight faculties of health sciences were asked to complete a survey in 2009. The objectives were to determine:

• existing figures for filled HPCSA specialist and subspecialist training posts

• why HPCSA training numbers have not been translated into filled posts e.g. because of unfunded or inadequate recruitment

• what additional specialist registrar training numbers are needed, and what increase is recommended for specialists, sub-specialists and dental specialists

• capacity and staffing requirements to train specialists, sub-specialists and dental specialists, and how to meet future staffing needs.

• The Presidents of the then 27 constituent colleges of the CMSA in 2009 were sent the available data and asked to complete a survey. They were informed that the outcome of the exercise was a practicable and pragmatic plan to increase the output of specialists and sub-specialists and that the survey was the first step. They were asked to:

• agree or disagree with the figures provided (and make adjustments)

• suggest an ideal staffing situation, and a pragmatic increase which would address, in part, health care needs

• motivate the reasons for the increase

• make any other suggestions about staffing requirements.

• The HPCSA's Register of Approved Registrar Posts for health sciences faculties was examined and results tabulated. This register is based on HPCSA accreditation site visits and includes approved training numbers for specialists and sub-specialists.

Results

WHO data

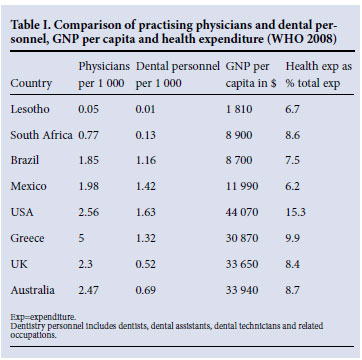

South Africa compares unfavourably with other middle-income countries in terms of medical and dental professionals per 1 000 population. In 2008,1 South Africa had 0.77 physicians (medical professionals) per 1 000 population, compared with Brazil (1.85), Mexico (1.8), the UK (2.47) and Australia (2.3) (Table I). The UK has 120 000 doctors for a population of 60 million; South Africa, with a population of 48 million, has 27 000 doctors. South Africa compares very unfavourably with other countries in terms of dentistry personnel (only 0.13 per 1 000 population) (Table I), compared with Brazil (1.16) and Mexico (1.42).

South African figures for doctors and dentists per 1 000 population

Several data sources were studied to establish the number of doctors and dentists in South Africa (Tables II - V). A 'best guess' estimate involved reviewing and collating data from various sources. This once-off effort is a useful exercise, but is limited as data quickly become outdated.

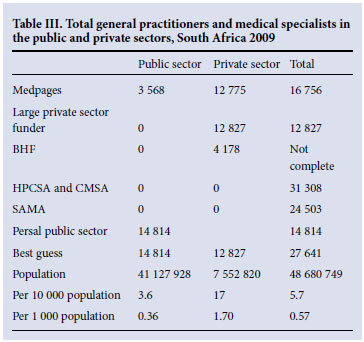

In 2009 there were about 9 765 medical specialists in the South African health sector - 5 532 in the private and 4 233 in the public sector. There are an estimated 14 814 medical professionals in the public sector (0.36 per 1 000 population) and 12 827 in the private sector (1.70 per 1 000 population), giving a total of 27 641 (0.57 per 1 000 population). This is a lower ratio than the WHO data in Table I (0.77 per 1 000).

Tables II and III show the results of data searching on numbers of doctors in South Africa in 2009.

A 'best guess' of dentists in South Africa revealed extremely low numbers of dentists and a low ratio per 1 000 population. There were 4 153 dentists (0.085 per 1 000 population) and few or no posts available to them in the public sector. The Community Dentistry speciality is a particular concern, with only 8 posts identified in South Africa (personal communication: Medpages 2011; Dr Barrie, UWC School of Dentistry, January 2011).

Survey of Deans of Faculties of Health Sciences 2009

The 2009 CMSA survey results of Deans of Faculties of Health Sciences are reported in Tables V - VII; 72.43% of HPCSA-approved registrar posts were filled, and only 53% of sub-specialist training posts were filled. Deans prioritised the funding and filling of existing posts before considering plans for expansion, but nevertheless proposed an increase of 8% for specialist trainees and 22% for subspecialist trainees. Deans provided motivation by speciality and sub-specialty for the proposed increases, and identified matters for consideration that affect expansion of specialist and sub-specialist output (Table V).

The numerical results of the deans' survey are summarised in Tables VI and VII. Table VII presents the results of the survey of dental deans. Despite the significant shortage of dental specialists, only 62% of dental specialist registrar training posts are filled.

Survey of Presidents of Constituent Colleges of the CMSA 2009

Table VIII summarises the responses to the survey of the Presidents of the constituent colleges of the CMSA. They recommended that a pragmatic increase would be from 8 743 to 13 614 specialists (56% increase). The Presidents suggested that the total number of specialists in the public and private sectors was 8 743, which differs from the figures in Table III that show a 'best guess' of 9 765 - or 10 229 according to HPCSA data. The difference is possibly due to double counting of specialists working in the public and private sectors, non-practising/retired specialists, and emigrants.

Review of the HPCSA 'Register of Approved Registrar Posts'

The HPCSA 'Register of Approved Registrar Posts' was analysed in 2010. Tables IX and X show data from HPCSA reports of site visits that recorded the total number of accredited registrar and sub-specialist training posts, and unfilled training posts; 38% of specialist and 75% sub-specialist training posts were unfilled. The HPCSA register numbers differ from the Deans' survey in Tables VI and VII, which could be due to the year in which the Faculty was visited by the HPCSA, and other factors. To implement a plan for the filling of training posts, Faculty and HPCSA data must be reconciled.

Costs of filling unfilled HPCSA training posts

The costs of filling unfilled HPCSA training posts were calculated (personal communication: Dr Mark Blecher, Social Sector National Treasury). Table XI shows the total cost of filling unfilled specialist and sub-specialist training posts over 5 years. Costs were calculated using only the costs of the registrar salary for a training period of 4 years for registrars and 2 years for sub-specialists (with a 6% cumulative annual increase for inflation). The costs of the service

sites where they are trained are not included as they are assumed to be academic site health-service costs and not part of the dedicated financing required for specialist and sub-specialist trainee salaries.

These costs must be taken into account but through a different funding stream. Academic clinician costs were also calculated for each speciality and sub-specialty. Not all newly filled registrar and sub-specialist training posts will require academic clinician appointments. The academic supervision cost per trainee based on 2009 salaries, and over 4 years, is R1 million to R1.5 million, depending on the speciality. Funds for registrar training posts should be ring-fenced to protect their training in line with national needs for medical and dental practitioners.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that South Africa has a poor ratio of doctors and dentists per 1 000 population, and many districts have limited or no access to specialist medical and dental services. The situation should never have developed. South Africa employs relatively few of its doctors and dentists in the public sector, and loses many to emigration.

From 1997 to 2006, there was a significant decline of 854 (25%) specialists and sub-specialists in the public sector (from 3 782 to 2 928). The number of medical practitioners (non-specialist) on the public sector payroll increased in the same period from 9 184 to 9 958, an increase of only 774 in 10 years (personal communication: Dr Nicholas Crisp, Benguela Health, 2010). The decline in specialists and sub-specialists, and limited increase in medical professionals in the public sector over 10 years, must be seen against the output of MB ChB and specialist graduates in South Africa. Table XII shows the graduates produced during the period 1998 - 2006, when specialist and generalist numbers on the public sector payroll were declining and stagnating. Over 9 years, 14 145 MB ChB and specialist graduates were produced.

These graduates are not being recruited into the public sector system; the reasons include: lack of policy to expand the number of medical professionals in the public sector; lack of planning; lack of finance and posts; poor working environment and working conditions; and very limited - to non-existent - career prospects in the public health services.2

A significant contributor to low retention has been lack of positive reinforcement for 15 years from DoH authorities to doctors. Doctors often feel undervalued, and some policy and financing incentives support this perception. The South African health and education system has, by omission and commission, implemented 'push factors' which send doctors away (Table XIII).3

The first step to improve management of staff needs for the South African health sector is to have a reliable database that supplies the numbers of health professionals, and trends in output and retention. The present study showed that there is no accurate and reliable database of health professionals, with information on location and type of employment, active or inactive, emigrated, etc. Therefore, trends are not monitored. Key trends are that the number of public sector specialists is declining despite an annual output of about 500, and only a tenth of medical graduates are absorbed into the public sector.

A central data source on medical, dental and other health professionals, which is monitored and updated annually, is urgently needed. It should be used to ensure planning and development of specialists, monitor placement and emigration, plan recruitment, and review specialist service activity. Such a database should be developed by collaboration between the parties who provided data for this research, and be publicly available. Examples of international electronic databases include the UK's www.specialistinfo.com and the Australian www.healthdirectory.com.au/medicalspecialists.

Table XIV details the data sources reviewed and their strengths and weaknesses. No single source is adequate for providing comprehensive data on health professionals.

Conclusion

Dynamic leadership and policy interventions are required to advocate and finance the planned growth of medical, dental and other health professionals, including specialists and sub-specialists. This effort must be accompanied by a strategy to retain doctors, careful assessment of working conditions, and active recruitment of doctors who have left the country and of foreign doctors who can contribute to South African health care development.5,6 The policy priority should be to consolidate training capacity by planning and funding the existing recommended HPCSA training posts within faculties of health sciences, and to send a positive message to South African doctors and dentists that the country values and needs them.

Postscript. As a result of the CMSA's project work in 2010, National Treasury agreed this year to allocate funds for filling unfilled registrar training posts over 5 years, as detailed and costed in this article.

Acknowledgement

The CMSA expresses its appreciation to funders for supporting this research that was part of its project 'Strengthening Academic Medicine and Specialist Training'. Funding was initiated through the CMSA Foundation (new Board of Trustees). The Discovery Foundation funding allowed development of the project and significant research. Other funders were the Medi-Clinic Hospital Group, Netcare Hospital Group, Metropolitan Health Group, Medscheme Health Risk Management, Old Mutual Health Risk Management, and Medical Advisors Groups of SAMA.

References

1 World Health Organization. WHO Statistical Information System (WHOSIS). http://www.who.int/whosis/indicators/compendium/2008/4mrn/en/index.html (accessed 15 March 2010). [ Links ]

2. Pendleton W, Crush J, Lefko-Everett K. The Haemorrhage of Health Professionals from South Africa: Medical Opinions. Cape Town: IDASA, 2007:2,6. [ Links ]

3. Ibid.:17. [ Links ]

4. Buchan J. Migration of Health Workers in Europe: Policy Problem or Policy Solution. In: Du Bois C, McKee M, Nolte E, eds. Human Resources for Health in Europe. Maidenhead, Berks., UK: Open University Press, 2006:44-52. [ Links ]

5. Mullan F, Frehyot S, Omaswa F, et al. Medical schools in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet 2011;377(9771):1113-1121. [ Links ]

6. Collins FS, Glass RI, Whitescarver J, Wakefield M, Goosby E. Developing health workforce capacity in Africa. Science 2010;330(6009):1324-1325. [ Links ]

Accepted 17 June 2011.

Corresponding author: B Strachan (bstrachan@telkomsa.net)