Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versão impressa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.101 no.7 Pretoria Jul. 2011

FORUM

HISTORY OF MEDICINE

A benefaction and its benefits: the Oxford Nuffield Medical Fellowship and South Africa

Colin Bundy

This is the history of an act of philanthropy: the creation of a Fellowship allowing scholars from Australia, New Zealand and South Africa to study postgraduate medicine at Oxford University. More specifically, it examines how a charitable fund has operated with respect to the South African clinicians and medical scientists who have been its beneficiaries for the past 60 years.

In 1938, Lord Nuffield (born William Morris) signed a deed of trust, creating the Dominion Scholarships Fund. To understand and assess this decision, it makes sense to locate the donation within the broader context of Nuffield's philanthropy, and especially his support for academic medicine at Oxford University.

Lord Nuffield and medicine at Oxford University

William Morris, born in 1877, left Cowley School at fifteen to enter an apprenticeship. His subsequent career was spectacular. From a tiny cycle repair business, he began to build bicycles, then to manufacture motorcycles - and next motor cars. Resuming car production after World War I, by the mid-1920s he headed a successful company based on mass production, a chain of dealerships, aggressive advertising and a reputation earned by his vehicles for reliability and ease of maintenance.1 By the late 1920s, Morris supplied one in every three cars made in Britain, and he 'dominated public perception of modern British industry between the wars'.2

If the name Morris lingers in the memory as a series of popular motorcars, the name Nuffield (Morris took the title Viscount Nuffield in 1938) resonates in contemporary Britain as a consequence of the magnate's sustained philanthropy. Like Carnegie or Rockefeller, 'it is what he did with his money, not how he made it' that has established his legacy.2 From 1926 onwards, Morris/Nuffield made almost a thousand separate charitable donations, culminating in the formation in 1943 of the Nuffield Foundation. Within this long history of giving, there was a strong thematic interest in developing medical care and expertise, and this expressed itself most strongly in the university town in which he lived and worked. Some accounts perpetuate the story that as a young man, Morris wished to study medicine but could not afford to do so,3 but this is probably apocryphal. Two authoritative sources stress his lifelong hypochondria - 'constantly anxious about his health' - and suggest that this was related to his concerns for matters medical.4 Be that as it may, there was no questioning the accuracy of the claim by Sir William Morris (as he then was) when he wrote to the Vice-Chancellor of Oxford in October 1936 that 'The progress of medical science and the conditions under which medical practice is carried on have long been ... among my main interests.'5

This letter set out the terms of the largest and most crucial act of support by Nuffield for the University, his major endowment of the Medical School. The story has been told frequently: how Nuffield grew close to a group including the Regius Professor of Medicine, Sir Farquhar Buzzard, and the surgeon Hugh Cairns; how he came to share their vision of a postgraduate school of clinical medicine in Oxford (turning the Radcliffe Infirmary from a provincial voluntary hospital into a first-class teaching base); how he offered the University £1.25 million to endow the scheme; and how, when Congregation met to approve the decree accepting the gift, he rose and spoke. As he was not a member of Congregation, his words were minuted as a 'disorderly interruption' - but they were hardly unwelcome. He had come to realise, he said, that more money was needed for the endowment and that he would increase his gift by a further £750 000! Nuffield was by the 1930s 'increasingly inclined to major schemes and grand gestures'; his 'instinct for monumental expression of his philanthropy thus came together with his long-standing commitment to the advancement of medicine'.6

A major scheme it certainly was. The gift of £2 million is roughly equivalent to £106 million at 2010 values (or R1.16 billion) - and it was followed by further tranches of £200 000 for the building fund and £300 000 to improve facilities and standards at the Radcliffe Infirmary.7 Another way of gauging the scale of Nuffield's support for the University is to note that between the wars Oxford received a total of £1.6 million in grants from the Exchequer - but £3.8 million from Nuffield. The munificence of the 1936 gift was acted upon rapidly and effectively. The first four Nuffield Professors (in Medicine, Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynaecology and Anaesthetics) were elected in 1937; other chairs were soon created in Pathology and Radiology; and these departments were developed as quickly as possible.

In 1938, noted his official biographers, 'Nuffield took steps to associate medicine in the Dominions with the new post-graduate medical school at Oxford by creating the Dominion Scholarships Fund, with a donation of £168,000.'8 From 1927, Nuffield had enjoyed annual long sea voyages, visiting Australia and South Africa on various occasions.9 Although this is speculation, it may be that these travels lay behind Nuffield's support for medical science in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. He had previously made gifts for orthopaedic treatment in Australia (£122 183) and New Zealand (£94 622), followed these 'by a comprehensive scheme for the development of orthopaedic treatment in South Africa' (£105 000), and was said to have 'always had a close personal interest' in these countries.10 Clearly the Fellowship the history of which is the subject of this article was an adjunct, a spin-off, of Nuffield's large-scale support for medical training and research at Oxford.

The Nuffield Medical Fellowships at Oxford

The trust created in June 1938 endowed a scheme whereby medical graduates from the three participating Dominions could attend Oxford University for postgraduate medical training and research. The charitable object of the scheme was 'to promote the progress of medical knowledge by co-operation between the Medical School of the University [Oxford] ... and such of the Universities of the Dominions Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa as provide facilities for medical research'.11 The terms of the trust were detailed, and as we shall see their specificity created difficulties in administering the award in future years. They created awards in two categories: three demonstratorships tenable in the preclinical departments (Human Anatomy, Biochemistry, Pathology, and Pharmacy and Physiology), and three clinical assistantships in the four Nuffield departments (Anaesthetics, Medicine, Obstetrics and Gynaecology, and Surgery). Henceforth all such awards will be referred to as Fellowships - as became the practice.

The appointment of Fellows to one or other of these Oxford departments would be made by the University, upon receipt of nominations from the participating universities: four in Australia, two in New Zealand, and in South Africa the universities of the Witwatersrand and Cape Town.

Eligibility for a demonstratorship required a degree and relevant research experience; a clinical assistantship required a degree and a medical qualification. A successful appointment would entitle the Fellow to three years of research or study towards a higher degree at Oxford. All recipients had to guarantee in writing that they would return to their respective country for at least five years after their tenure of the Fellowship, in order that they could contribute to the development of medicine there. Award of a Fellowship entitled the recipient to a stipend, a travel allowance, and for married Fellows, allowances for housing and per child. The language of the trust deed and correspondence around it invariably used the male gender: awards to women did not appear to exist in the imagination of those drafting the scheme. Although the funding for the Dominions Fellowships was entirely separate - it is worth noting that the £168 000 endowment in 1938 is worth about £8.4 million in 2010 prices - it was administered by the Nuffield Medical Trustees, appointed in terms of the larger 1936 benefaction to the University.

In one obvious respect, the timing of the scheme was blighted. In late 1938, the vice-chancellors of Wits and UCT wrote separately to the Registrar of Oxford University, apologising that it had taken some time to negotiate a scheme of rotation between the participating universities in three countries. It had been agreed (they reported) that the two South African universities would constitute a single nominating body to be allocated one demonstratorship and one assistantship every three years, and that the Australian and New Zealand universities would constitute a separate nominating body to receive two Fellowships in each category every three years. In terms of this agreement, it was anticipated that the first South African candidate would be nominated for the academic year 1939/40.12 But by the time such a candidate might have arrived for the Michaelmas term in 1939, England had declared war on Germany. Under the Emergency Regulations promulgated for the University, the workings of the scheme were suspended13 in September 1939.

During the war, from early 1940, the Trustees attempted to implement the scheme, but made only halting progress. The award of a single assistantship from South Africa illustrates the difficulties involved. In April 1940, the Vice-Chancellor of Wits wrote to the Registrar in Oxford about two candidates. A recently qualified medical graduate, Mr J F P Erasmus, wanted to work on neurosurgery, while a Miss Orford sought placement in the Oxford department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Both were eminently qualified for the Fellowship (wrote Raikes) 'although Mr Erasmus has somewhat the better personality and Miss Orford somewhat the better brain'. Oxford plumped for the 'better brain'. Margaret Orford was duly appointed as Clinical Assistant, but in February 1941, she 'had been unable to take up her appointment'. Her appointment was suspended. Halfway through November 1945, the dogged Miss Orford indicated that she hoped to arrive in Oxford at the end of the month; at the end of the month, she had amended this to 'in the near future'; and by March 1946, she was finally in Oxford.14

The exigencies of wartime travel and planning were only part of the problem. In January 1947, the Oxford Medical Board outlined operational difficulties in implementing the Dominions scheme. These arose from trying to align several systems of rotating entitlements. The 1938 Trust Deed specified that the eligible medical departments at Oxford take their turn - and that the Dominions universities should also nominate candidates in strict order. This proved too rigid a requirement. The field from which qualified candidates could be chosen in the Dominion universities was small, and if applications were called for 'in such a way that a particular university has to nominate a candidate in a particular field, it has happened that no-one has come forward, or at best only one or two candidates, none of whom may be entirely suitable'.15 The Trustees were persuaded; and amended the Trust Deed, relaxing the strict rotations of Oxford departments and partner universities.

By the late 1940s, the scheme had bedded down, and the supply of Fellows met the annual targets of three assistantships and three demonstratorships. As far as the South African universities were concerned, in 1950 UCT and Wits proposed that the University of Pretoria be added to the schedule of participating universities, and in 1957 the addition of the universities of Stellenbosch and Natal was approved by the Trustees.16 Administering the scheme was somewhat cumbersome in that the Trust Deed stipulated that any changes to its operation should be approved by all the participating universities. The Trust files bulge with pages of correspondence detailing the process of securing collective assent to changes in the levels of stipends and allowances; the total number of Fellows in post at any time (expanded in 1963 to eight per year); and so on.

A recurring concern for the Trustees was the stipulation in the original Trust Deed that Fellows should return to their own countries for at least five years after their work in Oxford. As early as 1941, it was explained that 'the authorities of Oxford University hope to avoid the faults of the Rhodes Scholarships'17 (apparently individual Scholars were staying on after completing their degrees). Individual circumstances meant that Fellows often chafed at this requirement: some were granted permission to stay in the UK for a period after their Fellowship had expired. In May 1966, however, a South African Fellow - Dr Laurence Geffen - raised a different issue for the Trustees to consider. His Fellowship was due to end in December 1966, but he 'informed the Secretary [of the Trust] that he did not wish to return to South Africa, that he had obtained a post in the Department of Physiology at Monash University ... his reason was simply that he was not prepared to live in South Africa'. The Trustees handled it pragmatically. They 'noted the possible difficulty on regard of return of appointees to South Africa, of which the case of Dr Geffen was an example, but while accepting that the situation was not unlikely to recur, agreed to take no action'.18 After considerable further correspondence with the participating universities, the Trustees reduced the requirement to return to the country of origin from five years to three. The only participating university not to agree to this change was the University of Stellenbosch.

With six participating South African universities (the University of the Orange Free State was added in 1971), the process of nominating candidates for the Fellowship became more complex. Initially a further system of rotations was proposed, but at some point in the 1970s the responsibility for selecting South African candidates for the Fellowship was delegated by the participating universities to their respective deans of Medicine. Under this arrangement, applicants for the Nuffield Dominions scheme appointments applied to the deans of their medical schools. The deans then proceeded to select a short-list of three, which were referred to the Oxford University for a final choice. In some years, the deans met; in others, their deliberations were conducted by correspondence.

The contemporary operation of the ONMF in South Africa

About two decades ago, a number of changes took place in the selection of Fellows, the administration of the programme, and relations between the South African universities and Oxford. Firstly, the Nuffield Medical Trustees undertook a substantial revision of the scheme, involving a number of amendments to the original Trust Deed. These provided for the award of additional Fellowships when funds permitted; introduced greater flexibility with respect to the maximum stay by Fellows in Oxford; increased the number of Oxford graduates who might take up appointments in the participating universities overseas; and gave the Trustees the power to make grants directly to the Oxford University for maintaining and improving equipment and facilities.19 Secondly, the award came to be advertised in South Africa as the Oxford Nuffield Medical Fellowship (ONMF) instead of the anachronistic, title of Nuffield Dominions Scheme.20 The Trust Deed was amended to refer to 'qualifying' universities instead of 'Dominion' universities.

Thirdly, the administration and selection process in South Africa was centralised. In 1990, Sir Henry Harris - previously Regius Professor of Medicine, and then a Nuffield Medical Trustee - visited South Africa, and held crucial meetings with various officers, but particularly with Professor Wieland Gevers, a Deputy Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cape Town. It was agreed between them that the selection process by the medical deans had exhausted its usefulness - indeed, was seen as 'clumsy and ineffective' with the actual selections being 'fairly haphazard'.21 In consequence, it was agreed that ONMF matters be handled centrally by a secretariat, initially located within Professor Gevers' office, and that a national selection panel be constituted. Similar centralising provisions were proposed for Australia and New Zealand. The Nuffield Medical Trustees approved these arrangements, and suggested that the selection committee in each country should include academics drawn from clinical and medical science, preferably with some knowledge of Oxford, and if possible, previous ONMF Fellows.22

A South African selection committee was constituted on this basis, chaired from 1991 until 2008 by Professor Gevers, and since then by Professor Barry Mendelow of the University of the Witwatersrand. As its files reveal, the committee's meetings were focused on close consideration of the applications for ONMFs, based on full CVs, as well as academic and professional references, for each candidate. Decisions were based upon academic merit, nuanced by particular considerations. These latter were articulated by the Chair in 1995:

The most important criteria used by the Selection Committee are related to the question as to whether the Oxford opportunity will provide a quantum jump in their ability to contribute to South African academic medicine in the future, i.e. the favoured candidate should be poised to make enormous progress in the powerful scientific community at Oxford and should then be in a position to bring developed skills and experience back to this country.23

These criteria were informed by an awareness of an 'opportunity deficit' affecting young medical scientists in South Africa. An emeritus Professor of Surgery spelled this out in a reference for a (successful) candidate:

The problem with many young so-called 'academics' in South Africa is that they have been appointed to their positions without having had the opportunity to develop themselves to their full capacity, and are tied down by administrative tasks which never allow them the ability to regain the lost ground of an adequate research opportunity.24

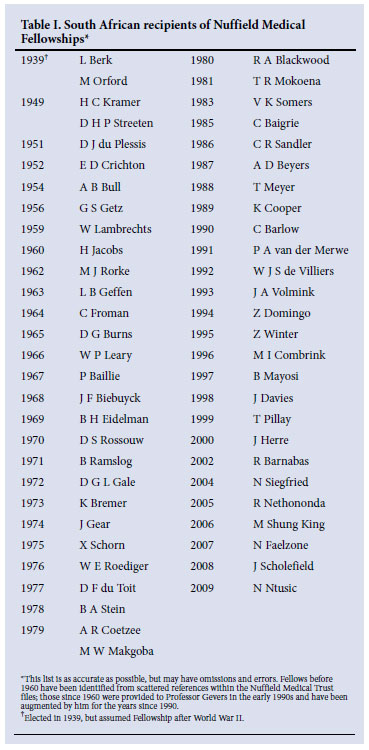

In the light of this brief history, how might one assess the impact in South Africa of the ONMF over the years? One answer reflects the requirement present since the scheme was initiated: that the young clinicians and scientists who benefited from their years in Oxford should return to their own countries. As noted above, this stipulation has remained a live issue for the Nuffield Medical Trustees ever since 1938, generating correspondence in each subsequent decade. Noteworthy, then, is the report by the Chair of the South African Selection Committee in May 2000: 'The Nuffield Fellowships have a proud record in this country and the scheme has been uniquely successful in terms of the percentage of Fellows actually spending their major careers in this country.'25 A glance at Table I, which lists South African Fellows, illustrates the point. A majority of the recipients have enjoyed distinguished careers in academic medicine in South Africa. Several have taken up leadership positions in universities and other institutions - none more strikingly so than Professor Malegapuru Makgoba, previously President of the Medical Research Council and currently Vice-Chancellor of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, or Professor Taole Mokoena, a past Chair of the MRC Board and director of a wide range of private and public sector entities.

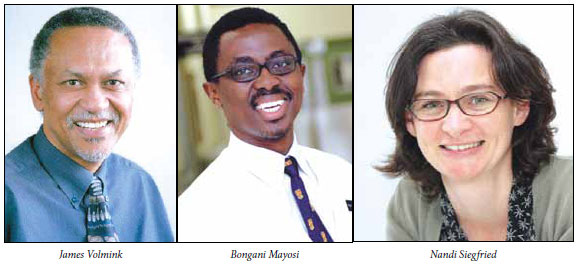

But perhaps the most effective way of demonstrating how the ONMFs provided young clinicians and medical scientists with 'the opportunity to develop themselves to their full capacity' is to allow them to speak for themselves. Professor James Volmink (currently Dean of the Faculty of Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University) was appointed to the Fellowshipin1993.Heappreciatedthat theterms of the Fellowship (which have operated throughout its history) provided a salary and family support. This was 'a rare and special privilege. There aren't many Fellowships that allow clinicians to take time out to complete a doctoral degree, without severe loss of earnings.' The academic and intellectual experience he found 'magical': the concentration of academic talent across the medical disciplines, and the college system which facilitated contact with so many scholars, 'has led to ongoing interaction or research collaboration to this day' (personal communication, 20 February 2011). Professor Bongani Mayosi (Fellow in 1997, currently Professor and Chair of Medicine at UCT) sounds a similar note: 'The award of the Nuffield Fellowship was the "turn-key" factor in my scientific development and academic career in general. I benefited immensely from the rich intellectual environment and I built relationships and networks that have facilitated my work to this day' (personal communication, 9 December 2010).

Professor Richard Nethononda is one of the most recently returned Fellows (he was appointed in 2005), and he also provides a grateful assessment of his Oxford experience: 'For me the opportunity to study in Oxford was fulfilment of a childhood dream ... In Oxford I met and had the opportunity to interact directly with and was mentored by some of the world's brightest and enquiring minds ... I left South Africa with little appreciation of the value of research and synthesis of new knowledge, and return fully equipped and competently trained ... My career path has widened with multiple avenues, but more importantly, I am more able effectively to serve and make a difference to ordinary South Africans' (personal communication, 17 February 2011).

Finally, a reflective and acute commentary on the ONMF experience was provided by Dr Nandi Siegfried, appointed as Fellow in 2004. She was a diffident applicant, unsure that her location within public health medicine (as a clinical epidemiologist) would make her a likely candidate. She was successful, however, and completed her DPhil at the renowned Clinical Trials Service Unit in Oxford, keen to apply her doctoral expertise to the field of HIV/AIDS epidemiology in South Africa. The intellectual and collegial value of her Oxford years was immense. It gave her the confidence 'to know that my research could hold its own internationally ... it gave me the certainty that public health medicine is as important as internal medicine, paediatrics and surgery'. She also mentioned 'softer' elements of the award: the welcome afforded her by the head of her Oxford college; the intimate and relaxed environment provided by the college; and that the Fellowship salary made it possible to have her spouse and daughter with her in Oxford (personal communication, 2 March 2011).

Testimonies like these are important, not only in their individual detail but also in their cumulative narrative. The scheme has been amended, adjusted and expanded over the years since 1938. But it is striking how effectively the Nuffield Medical Fellowship continues to fulfil its original intention, spelled out over 70 years ago: to 'promote the progress of medical knowledge' by a scheme of co-operation between Oxford and the medical schools of Australian, New Zealand and South African universities.

1. Overy RJ. Morris, William Richard, Viscount Nuffield, in Dictionary of National Biography, online edition, January 2011. http:/ezproxy.ouls.ox.ac.uk:2117/view/article/35119 (accessed 23 March 2011). [ Links ]

2. Adenay M. Nuffield: A Biography. London: Robert Hale, 1993:9. [ Links ]

3. Cook A. My First 75 Years of Medicine. London: Royal College of Physicians, 1994:39. [ Links ]

4. Adenay M. Nuffield: A Biography. London: Robert Hale, 1993:174-175. [ Links ]

5. Andrews PWS, Brunner E. The Life of Lord Nuffield: A Study in Enterprise and Benevolence. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1955:288. [ Links ]

6. Webster C. Medicine. In: Harrison B, ed. The History of the University of Oxford. Vol. VIII: The Twentieth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994:323, 325. [ Links ]

7. Veale D. The Nuffield Benefaction and the Oxford Medical School. In: Dewhurst K, ed. Oxford Medicine. Oxford: Sandford Press, 1970:147. [ Links ]

8. Andrews PWS, Brunner E. The Life of Lord Nuffield: A Study in Enterprise and Benevolence. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1955:292. [ Links ]

9. Adenay M. Nuffield: A Biography. London: Robert Hale, 1993:139-140. [ Links ]

10. Andrews PWS, Brunner E. The Life of Lord Nuffield: A Study in Enterprise and Benevolence. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1955:297, 292. [ Links ]

11. Bodleian Library, Nuffield Dominions Trust papers, UR6/MD/13/7/file 1 [1937-40] draft deed of scheme. [ Links ]

12. Oxford Medical Sciences Division archives, Nuffield Medical Trustees, circulated papers December 1936 - July 1944, TP (Trustees' Papers) 26, H R Raikes to D Veale, 17 October 1938 and TP 28, A M Falconer to D Veale, 1 November 1938. [ Links ]

13. Oxford Medical Sciences Division archives, Nuffield Medical Trustees, Circulated Papers December 1936-July 1944, TP 39. [ Links ]

14. Bodleian Library, Nuffield Dominions Trust papers, UR6/MD/13/7/file 1, H R Raikes to Registrar, 25 April 1940; file 2, February 1941; 16 November 1945; 30 November 1945; March 1946. [ Links ]

15. Oxford Medical Sciences Division archives, Nuffield Medical Trustees, Circulated Papers May 1945 -July 1951, TP 112, Medical Board report 16 January 1947. [ Links ]

16. Bodleian Library, Nuffield Dominions Trust papers, UR 6/MD/13/7 file 4, 6 November 1950; and file 6, February 1957. [ Links ]

17. Bodleian Library, Nuffield Dominions Trust papers, file 2, January 1941 - July 1946. [ Links ]

18. Bodleian Library, Nuffield Dominions Trust papers, file 7, Minutes of the Nuffield Medical Trustees 5 May 1967. [ Links ]

19. University of Cape Town Administrative Archives, Donations N 1992-96 8.4.1. (08) folder Nuffield Dominions Trust, Ms J Moon (Secretary of Nuffield Medical Trustees) to Professor S J Saunders, Vice-Chancellor UCT, 25 October 1993. [ Links ]

20. See advertisement inviting applications in Sunday Times 11 September 1988, indicating the change of nomenclature. [ Links ]

21. University of Cape Town Administrative Archives, Donations N 1992-96 8.4.1. (08) folder Nuffield Dominions Trust, Professor W Gevers to Mrs E Marston, 28 October 1993. [ Links ]

22. Papers of the ONMF Selection Committee, Files in possession of Professor W Gevers, 1991, Miss E Reeve (Medical School Office, Oxford) to Professor Gevers, 15 February 1991. [ Links ]

23. Papers of the ONMF Selection Committee, Files in possession of Professor W Gevers, 1991, Professor W Gevers to Professor S R Benatar, 11 January 1995. [ Links ]

24. Papers of the ONMF Selection Committee, Files in possession of Professor W Gevers, 1991, Professor J C de Villiers to Professor Gevers, 17 January 1994 (reference on behalf of Dr Z Domingo). [ Links ]

25. Papers of the ONMF Selection Committee, Professor W Gevers to Dr G Fox, 24 May 2000. [ Links ]

Colin Bundy is a historian who recently retired as Principal of Green Templeton College, Oxford, after an academic and administrative career in South Africa and the UK.

Corresponding author: C Bundy (colin.bundy@gtc.ox.ac.uk)