Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versión impresa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.101 no.6 Pretoria jun. 2011

FORUM

HEALTH POLICY

How different are the costs and consequences of delayed versus immediate HIV treatment?

Alex Welte; John Hargrove; Wim Delva; Brian Williams; Tienie Stander

A recent major report, commissioned by the South African Government, examines alternative long-term scenarios for the costs and benefits of HIV prevention and treatment, and care for orphans and others affected by AIDS in South Africa.1 Not considered by the report is what one might call 'treatment-centred prevention' (TcP), by which we mean a combination of regular testing for HIV, immediate highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) offered to all infected individuals, and other proven HIV prevention methods. Such an approach could dramatically reduce infectiousness of HIV-positive people, leading to critical reductions in the rate of new infections.

The concept behind TcP, which has attracted considerable attention of late, has also caused much controversy.2-10 Indeed, TcP faces serious challenges, including the logistical and human resource constraints of the South African health system,11 unknown acceptability of regular testing and early treatment, the risk of treatment side-effects and drug resistance,12 and the huge immediate costs of offering antiretrovirals to any HIVpositive person, regardless of CD4 count or stage of disease.13-15

But is there really such a big difference in the ultimate costs between the TcP approach and current strategies where people can be treated only when they have sufficiently advanced disease? Few would dispute that infected individuals should start treatment before they are at substantial risk of death, but also before undue morbidity and associated health care costs are incurred as a result of untreated HIV infection. Any defensible treatment plan therefore already aims to offer HIV care and support to the majority of those infected, for the period of remaining post-treatment life expectancy - possibly several decades.16,17 Hence, the ultimate cost difference between treating people very soon after infection versus 5 or so years later, is then not a large proportion of the total treatment cost of TcP.

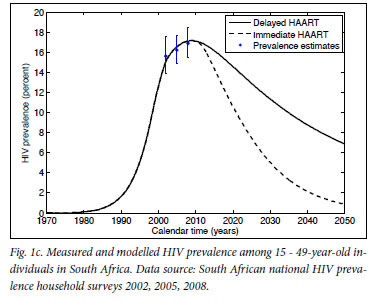

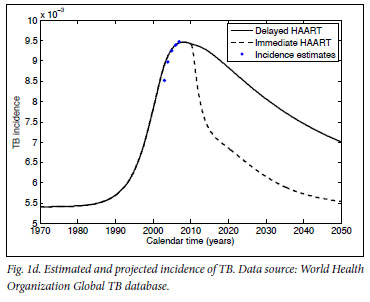

The effects of immediate versus delayed HIV treatment on the incidence of HIV, however, are likely to be vastly different. Whereas the former strategy offers suppression of the viral load after a short period of time - on average, half the interval between consecutive HIV tests - the latter only does so after several years of potential onward HIV transmission. Earlier initiation of HIV treatment also confers protection against TB, as the hazard of active TB increases with declining CD4 count.18-20 In people on HAART, this hazard is reduced by 60%.21

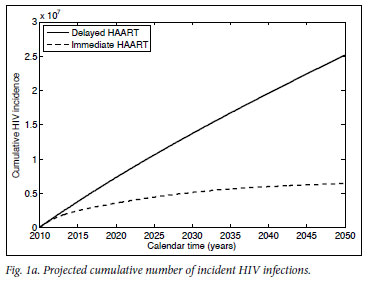

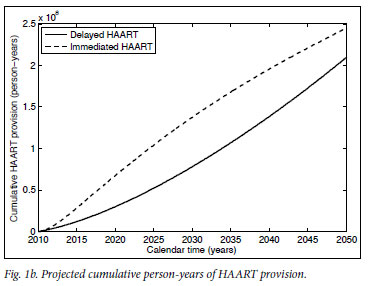

Mathematical model projections for scenarios of immediate versus delayed HAART initiation support the intuitive statements on the comparable costs and diverging effects of these alternative treatment strategies (Fig. 1). For the first 10 years of TcP, the cumulative number of person-years on HAART would be about double of what we expect under the current treatment policy. Lower HIV incidence rates under TcP would result in a decreasing need for HAART initiation, in contrast to the sustained pool of people in need of HIV treatment if treatment remains delayed until several years after infection (cf. Figs 1a, 1b). A substantially reduced HIV prevalence under TcP, in combination with the protective effect of HAART on TB, explains why TcP could have a large influence on the incidence of TB (Figs 1c, 1d).

In conclusion: regardless of our approach to treatment, we are inevitably faced with the problem of funding and administering a treatment programme of unprecedented size, complexity and cost for decades to come. If the indirect costs to society of HIV-related morbidity and mortality are taken into account as well,22,23 deferred HAART initiation becomes the more expensive rather than the cheaper option. The important point is that the current treatment policy does little to reduce the rate of new infections, but does ensure that people are sicker, and require more medical attention and expenditure, when they start treatment. TcP is one of the few credible plans to turn off the tap of new infections, providing real hope that we can reduce the HIV epidemic to negligible levels. The choice that South Africa faces is not between spending much more or considerably less money on HIV treatment - it is about attempting to eradicate HIV over the next two generations, or accepting endemic levels of HIV infection, quite probably for many more generations.

1. aids2031 Costs and Financing Working Group. The Long-Term Costs of HIV/AIDS in South Africa. Washington, DC: Results for Development Institute, 2010. [ Links ]

2. De Cock KM, Crowley SP, Lo YR, Granich RM, Williams BG. Preventing HIV transmission with antiretrovirals. Bull World Health Organ 2009;87(7):488-488A. [ Links ]

3. Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet 2009;373(9657):48-57. [ Links ]

4. Del Romero J, Castilla J, Hernando V, Rodriguez C, Garcia S. Combined antiretroviral treatment and heterosexual transmission of HIV-1: cross sectional and prospective cohort study BMJ 2010;340:c2205. [ Links ]

5. Donnell D, Baeten JM, Kiarie J, et al. Heterosexual HIV-1 transmission after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet 2010;375(9731):2092-2098. [ Links ]

6. Granich R, Crowley S, Vitoria M, et al. Highly active antiretroviral treatment for the prevention of HIV transmission. J Int AIDS Soc 2010;13:1. [ Links ]

7. Granich R, Crowley S, Vitoria M, et al. Highly active antiretroviral treatment as prevention of HIV transmission: review of scientific evidence and update. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2010;5(4):298-304. [ Links ]

8. Montaner JS, Lima VD, Barrios R, et al. Association of highly active antiretroviral therapy coverage, population viral load, and yearly new HIV diagnoses in British Columbia, Canada: a population-based study. Lancet 2010;376(9740):532-539. [ Links ]

9. Wagner BG, Kahn JS, Blower S. Should we try to eliminate HIV epidemics by using a 'Test and Treat' strategy? AIDS 2010;24(5):775-776. [ Links ]

10. Dieffenbach CW, Fauci AS. Universal voluntary testing and treatment for prevention of HIV transmission. JAMA 2009;301(22):2380-2382. [ Links ]

11. Bärnighausen T, Bloom DE, Humair S. Universal antiretroviral treatment: the challenge of human resources. Bull World Health Organ 2010;88(12):951-952. [ Links ]

12. Wagner BG, Blower S. Voluntary universal testing and treatment is unlikely to lead to HIV elimination: a modeling analysis. Nature Precedings 2009 http://precedings.nature.com/documents/3917/version/1 (accessed 2 December 2010). [ Links ]

13. Leisegang R, Cleary S, Hislop M, et al. Early and late direct costs in a Southern African antiretroviral treatment programme: a retrospective cohort analysis. PLoS Med 2009;6(12):e1000189. [ Links ]

14. Wagner B, Blower S. Costs of eliminating HIV in South Africa have been underestimated. Lancet 2010;376(9745):953-954. [ Links ]

15. Cleary SM, McIntyre D. Affordability--the forgotten criterion in health-care priority setting. Health Econ 2009;18(4):373-375. [ Links ]

16. van Sighem AI, Gras LA, Reiss P, Brinkman K, de Wolf F. Life expectancy of recently diagnosed asymptomatic HIV-infected patients approaches that of uninfected individuals. AIDS 2010;24(10):1527-1535. [ Links ]

17. Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet 2008;372(9635):293-299. [ Links ]

18. van der Sande MA, Schim van der Loeff MF, Bennett RC, et al. Incidence of tuberculosis and survival after its diagnosis in patients infected with HIV-1 and HIV-2. AIDS 2004;18(14):1933-1941. [ Links ]

19. Venkatesh PA, Bosch RJ, McIntosh K, Mugusi F, Msamanga G, Fawzi WW. Predictors of incident tuberculosis among HIV-1-infected women in Tanzania. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2005;9(10):1105-1111. [ Links ]

20. Glynn JR, Murray J, Bester A, Nelson G, Shearer S, Sonnenberg P. Effects of duration of HIV infection and secondary tuberculosis transmission on tuberculosis incidence in the South African gold mines. AIDS 2008;22(14):1859-1867. [ Links ]

21. Williams BG, Granich R, De Cock KM, Glaziou P, Sharma A, Dye C. Antiretroviral therapy for tuberculosis control in nine African countries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010;107(45):19485-19489. [ Links ]

22. Badri M, Maartens G, Mandalia S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of highly active antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. PLoS Med 2006;3(1):e4. [ Links ]

23. Collins DL, Leibbrandt M. The financial impact of HIV/AIDS on poor households in South Africa. AIDS 2007;21 Suppl 7:S75-81. [ Links ]

Accepted 20 December 2010.

Alex Welte, John Hargrove, Wim Delva and Brian Williams are affiliated to SACEMA (the South African Centre for Epidemiological Modelling and Analysis) at Stellenbosch University;

Wim Delva is also affiliated to the ICRH (International Centre for Reproductive Health) at Ghent University, Belgium; and

Tienie Stander is the CEO of heXor (Health Econometrix and Outcomes Research), Midrand, Gauteng.

Corresponding author: W Delva (Wim.Delva@UGent.be)