Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versión impresa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.101 no.5 Pretoria may. 2011

IZINDABA

Libya - a South African doctor's story

In spite of UN-sanctioned air 'support' and pin-point strategic bombing to reduce civilian casualties, Libya's rebel fighters remain relatively easy targets for Gaddafi's ground forces because of their 'chaotic and aimless leadership'.

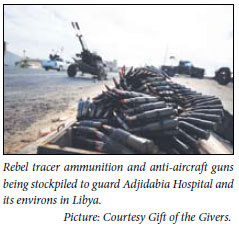

This is the opinion of Dr Imtiaz Sooliman, founder of Gift of the Givers (GOTG), and chief architect of a humanitarian South African medical rescue mission to that country last month, a week before the aerial no-fly zone was enforced. Besides saving dozens of lives of rebel Interim Transitional National Council (ITNC), fighters and civilians at Adjidabia and Benghazi hospitals, the South African team of 10 doctors (among them several Libyans working in South Africa), passed on vital trauma treatment skills to less experienced local medics.

Sooliman, whose war-zone experience as a GOTG medic includes conflicts in Bosnia, Lebanon and the Gaza Strip over the past 18 years, was asked how the short-lived Libyan experience compared. Similar in many respects, he replied, but with one striking difference. That was the 'total lack of capacity, administration, management or leadership', either in the health care infrastructure or among the rebel forces.

Casualty overrun byincoherent civilians

'In the hospitals we had 25 guys bringing one gunshot victim into casualty - you can imagine the chaos, with everyone shouting. We had gunfire and bombs in the background all the time; but it's the chaos that sticks,' he said. From what he could see, the rebels seemed 'best at chanting victory songs and waving flags - they don't organise resistance or communication systems. Because of the lack of systems and management, they'll lose the war in a hopeless manner,' he predicted. Sooliman cited television footage he saw of two different battlefront rebel groups arguing heatedly on what to do next.

The advance doctor team (of five Libyans working in South Africa) managed to enter Libya with the tenuous official help of the Egyptian ambassador to South Africa, Dr Muhammad Zayyid and the Egyptian Medical Council. These doctors, accompanied by nearly R350 000 worth of vital donated medical equipment, reached Adjidabia on 7 March, amid heavy aerial bombardment by Gadaffi's air force.

They immediately faced hundreds of casualties, mostly civilians, pouring in from the nearby Rus Lanov and Brega oil fields and found themselves working 16 -18 hours at a stretch. Three days later the back-up GOTG team, accompanied by a large contingent of South African journalists and a similar quantity of medical supplies, arrived at Adjidabia District Hospital. There was however a sudden and mad wholesale scramble just three days later when they heard that Gadaffi's forces were only 30 km away. The entire medical team, journalists and patients evacuated. Twenty hours later the hospital was hit by a bomb. The entire contingent travelled in a convoy of ambulances, bakkies and cars to Benghazi, 160 km away, taking nearly three hours as they negotiated their way past various friendly-force checkpoints.

Steady retreat by doctors, patients and journalists

By 15 March Adjidabia was surrounded and being overrun by Gadaffi forces which had also begun advancing on Benghazi, prompting a sudden decanting of Benghazi hotels and placing Sooliman in a predicament over his team's safety. 'I decided we should stick around a little, based on the need' - a trickle of overflow patients from the bombed Adjidabia hospital had managed to get out and reach Benghazi while many superficially treated local patients needed urgent help.

With the vivid mental picture of a 22-year old woman with chest and abdominal injuries and ruptured arteries dying on a Benghazi operating table after half an hour of 'touch-and-go' surgery and Gaddafi jets strafing the outskirts of Benghazi, Sooliman finally gave the order to pull out.

He cited three main reasons. The first was that if his Libyan doctors, originally from Tripoli in the west (Gaddafi territory), were found in the east, they would be summarily executed as 'traitors'. The second was the large contingent of South African journalists in the context of eight missing journalists from the BBC and the New York Times and an El Jazeera journalist killed by a sniper, while the third was the now undeniable accelerating advance on Benghazi.

The decision proved timely. 'Exactly 12 hours' after they headed out on the desert road via Tobruk to the Egyptian border, Gaddafi's jets mounted a 'huge' aerial attack on Benghazi. Ironically the United Nations 'no-fly zone' and defence of civilians was first enforced by French jets on 19 March, just a few days after the GOTG team left. The UN jets pulverised several convoys of Gaddafi tanks on the outskirts of Benghazi, buying time for the resistance to regroup and the local medics left behind to save more lives.

The South African team was left to ponder and evaluate their brief but valuable intervention.

SA trauma expertise 'invaluable'

Sooliman said he decided trauma assistance was needed in Libya when it became clear by 23 February that Gadaffi was going to cling to power and had begun attacking defenceless citizens. The real catalyst however was when he received an anxious call from a Libyan doctor working in South Africa. 'It was obvious they had a scarce skills shortage and that we have unique trauma skills to offer (the advance team of five Libyan doctors working in South African public sector hospitals had three years of trauma experience under their belts).'

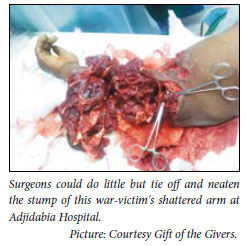

Asked to describe the closest shave of any team member, Sooliman said that an explosive device carried by a child in an Adjidabia Hospital passage detonated, blowing off her fingers and spraying shrapnel within millimetres of Dr As'ad Bhorat, the team's anaesthetist and Dr Livan Turino, their orthopaedic surgeon. Both were prepping a gunshot wound patient when the explosion happened.

'I suppose you could say that at every moment we were not at the wrong place at the wrong time, which makes you think ... but I'll also take with me the pitiful plight of refugees at the border, the docile nature of ordinary Libyans, their total unpreparedness for war, the poverty, under-development, the terror, the torture, the incarceration and the summary executions (they were told of while there).'

Chris Bateman