Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versión impresa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.101 no.2 Pretoria feb. 2011

IZINDABA

Life on the inside; coming out - Lex's story

Ever since he can remember (at least from around 3 -5 years old), Lex Kirsten (born a girl) identified himself as a boy. His deepest wish was that 'maybe if I wake up tomorrow my body will be right ... that there's been a big mistake'.

Instead he ended up always trying to hide it. 'I didn't feel I could tell anybody because they'd think I'm bad or that there was something wrong with me. The clothes I liked to wear and the things I liked to play with were always of the opposite sex.'

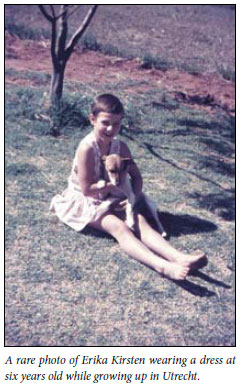

Growing up in Utrecht until the age of 7 and then moving with his family to Phalaborwa didn't exactly provide the optimal social context in which to adjust to gender incongruence, let alone living with a mother and two older sisters who disapproved of his behaviour.

A middle-child with sisters 3 and 4 years older 'who didn't like me very much - we had lots of fights' and two brothers, 8 and 15 years younger, Lex found his dad to be 'sort of OK, especially when I was young'. His mother was 'distant' and treated him differently and, together with his grandmother, kept on making comments like 'I should be doing this, wearing that, grow my hair longer - I felt like I was constantly living under a lid. I couldn't just be who I am. You try all sorts of things, pray that you'll come right. I tried being religious, everything I could, just to let it make sense to me. I think I was too rough for my sisters or something - sometimes they'd make fun of me and call me names'.

Growing up Erika, as he was christened, cross-dressed but kept under the radar by wearing a dress to church and school, changing back into shorts the moment he got home. By his early 20s Lex, who took his dad's second name (Alexander) but shortened it to sound gender-neutral, 'avoided pretty dresses' and stuck to 'female slacks and a skirt now and then but over the years I allowed myself to be me more and more'. It seemed natural to have a preference for women so he 'came out as sort of a lesbian', which was a poor fit, but had to suffice. The problem was that in telling people he was a lesbian he was also telling them that he was a woman.

No label could fit

'It was a bit of a struggle, but I had to accept that was all I could describe myself as. It was a big issue for my mother again but she finally accepted it - until I wanted to change my gender. Then she got very upset and asked why I can't stay a lesbian'.

He began by 'getting rid of this chest of mine' (a mastectomy in 1994) and later followed up having the areola of his nipples reduced, an experience in which he 'got the feeling' that the plastic surgeon involved 'really prefers working on women'.

By2004,whenhewas40andwellintohiscareer as a mechanical engineer (a 'reactor operator' at Koeberg Power Station in Cape Town, where khaki pants and blue shirts are blessedly standard uniform among his peers), Lex had 'had enough' and decided to 'get to the bottom of this gender feeling and issue and have resolution'.

He met a woman who was going out with a transman and who told him about sex-change operations being done at Pretoria Academic Hospital. A call to the psychiatrist on the Pretoria team to check on what was available locally resulted in a vague referral to Stellenbosch University or Groote Schuur Hospital (GSH), which he discovered dealt only with depression (the GSH Transgender Clinic had yet to be established).

'My journey really started when I heard about a support group at the Triangle Project and met other transwomen (there were unfortunately no transmen in the group then). Sexologist,localpioneerandGenderDynamiX board member, Dr Marlene Wasserman, referred him to an endocrinologist where he began his hormone treatment before going to a gynaecologist for, as Lex so blandly puts it, 'the removal of my (other) female parts'.

He explains that he had a hysterectomy and ovarectomy, but to date has avoided a phalloplasty, though he is now saving the R100 000 needed for a metoidioplasty -repositioning and enlarging of the clitoris (the latter via hormone treatment) plus a relatively complicated extension of the urethra, 'so you can pee through it'. The labia are fused together for a testicular implant. The operation is best conducted in Serbia, where surgeons have come to specialise in the procedure which, according to Lex, is only done experimentally in South Africa. He's told that erections (and orgasm) will be possible, with the only limit being penetrative sex. 'The result is very natural but the downside is that you're very small. Lex sees the potential complications of a phalloplasty as a far greater risk, even though the procedure is regularly performed locally.

A shift in sexual orientation

I steer him back from his gender incongruence to that other taboo - sexual preference - and ask for an update ... where's he at now? He, somewhat obviously, no longer considers himself a lesbian. 'I don't identify with that anymore. My sexual orientation did change a bit and I'd consider myself bisexual now. A lot of the time when people transition they're expected to be totally straight. If you dare say you're gay or so they say why didn't you stay a woman if you wanted to be with a man? I don't want to be a woman; I want to be a man; that doesn't mean to say I can't be attracted to a man as well!'

Along his journey Lex has grown closer to men and more distant from women. 'It's a kind of weird thing. What put me off men tremendously is that they saw me as a woman. I didn't want anything to do with them on a friendship or more than friendship basis. It didn't work for me. Now when I'm treated as a male it's fine to be close to men as well.'

The gender activist moves to have the DSM V definition changed from Gender Identity Disorder to Gender Incongruence, start to ring bells. Asked to pinpoint the most traumatic stages of his journey, Lex says being unable to find medical professionals to help him (though when he 'came out' to his GP, she was 'really accepting and very nice') and battling to get recognition for his gender from Home Affairs were nightmarish. 'The lady behind the counter at Wynberg Home Affairs said no such forms existed, that is was not in the law and gave me quite a hard time. It was quite embarrassing with other people standing around. In the end I went to Cape Town, where they were much friendlier.' The other difficult time was when his hormone treatment kicked in and people began calling him 'sir' - until he took out his credit card or ID book and much foot shuffling and eye aversion, or outright confusion, ensued. 'They then either apologise or are totally confused, so when my paper work was finally in line it was a huge relief.'

Lex speaks of a transman friend who, after paying at the till of a major discount warehouse in Ottery, was accosted by security to explain why he was using a woman's credit card.

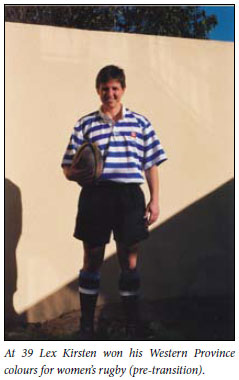

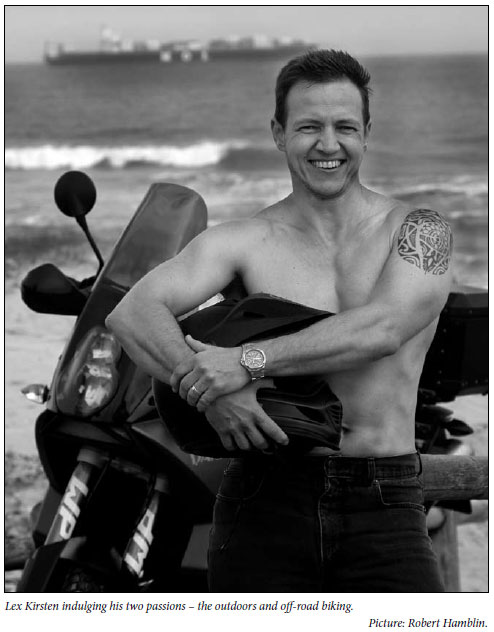

Keen on any endurance extreme sports, rugby, athletics and gym, Lex is an outdoors man who loves touring on his bike. Like most people, he has his views on the much-maligned athlete, Casper Semenya, and the controversy she has attracted. 'Obviously there's a wide variety of intersex conditions. What must they do? If an athlete feels like they're one gender or another, they mustn't be disqualified. On the other hand, if somebody has more testosterone than normal females it obviously benefits them and I can understand why people get upset. I always look at it this way: you get two people competing; one is genetically more gifted and one might be taller or shorter or have more muscles than the other guy and that's not really fair, it's just the way they were born, so they must deal with it - it's part of life - and life's not fair.'

Speaking of fair, his experience of health care professionals has been pretty mixed.

Besides the initial psychologist who asked him to demonstrate how he would hold a baby and then refused to refer him onwards, the 'uncomfortable' nipple-altering plastic surgeon and an endocrinologist who was happy to treat his diabetes but not his gender incongruence, the rest either referred appropriately or took the trouble to read up on what he presented.

His message to doctors echoes that from many of the health care professionals who specialise in helping gender-incongruent patients. 'Be open-minded and treat the person with respect. If you don't know and are not qualified to deal with transsexual people or you're not comfortable, that's also fine but treat them with respect and try and help or refer or make it your point of interest.'

Chris Bateman