Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versión impresa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.100 no.12 Pretoria dic. 2010

FORUM

HEALTH POLICIES AND PRACTICE

Can disease control priorities improve health systems performance in South Africa?

L C Rispel; P Barron

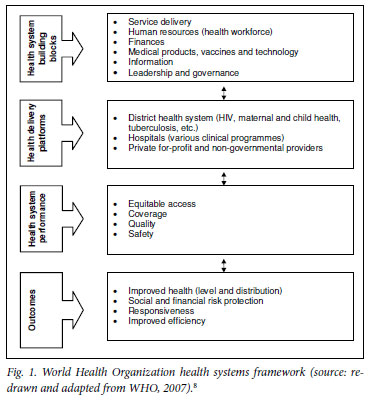

Improving health systems performance in order to achieve good health care outcomes and meet the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) has received increased global attention. Using the World Health Organization (WHO)'s framework on health system strengthening, an overview is presented of key aspects of performance of the South African (SA) health system that are likely to impact on the Disease Control Priorities (DCP) initiative.

SA is gripped by a complex disease burden, consisting of the twin epidemics of HIV and tuberculosis, as well as non-communicable diseases and injuries. Despite an enabling legal and policy framework, health system challenges include sub-optimal leadership, insufficient resources for many national policies, lack of a broad public health approach to service delivery, and poor utilisation of existing information for decision-making.

Provided that these and other health systems issues are addressed, cost-effectiveness studies and interventions may be beneficial in improving the functioning of the health system in SA and in getting better value for money.

Background

In the past few decades, the combination of biomedical and technological advances, a substantial increase in global knowledge to improve population health, and improved access to primary health care, essential drugs, water and sanitation has resulted in aggregate worldwide improvements in the health of individuals and communities.1-2 However, this progress has been marred by a multiplicity of factors, including globalisation, changing burden and complexity of disease profiles, inequalities between and within countries, and inadequate or poorly performing health systems.1 Common shortcomings of contemporary health systems include fragmented, unsafe and misdirected care, which mitigates against a comprehensive and balanced response to health needs.1

Improving health systems performance to achieve good health care outcomes and meet the MDGs has received increased global attention, especially in the last decade.1,3-9 In SA, the current health political leadership has committed itself to a substantial overhaul of the public health sector in order to address the complex burden of disease; improve health outcomes, access and affordability; and ensure responsiveness to the needs of the population.10 The DCP project in SA aims to determine which effective interventions should be included in a package of care that offers the greatest gain in health (or averted disease burden) per SA rand spent.11 The DCP can contribute to health policy changes and improve and prioritise health resource allocation and spending provided that it takes account of the existing issues and challenges in the health system and pays attention to process and those stakeholders who have the potential to take forward, block or challenge policy change or implementation.

Using the WHO's framework on health systems strengthening, we present an overview of key aspects of performance of the SA health system that are likely to impact on DCP-SA. Critical issues are suggested that must be taken into account in the execution of DCP-SA.

Measuring health systems performance

The measurement of health systems performance is not straightforward, as health systems are complex, consisting of all organisations, people and actions whose primary intent is to promote, restore or maintain health.6-8 Measurement tends to focus on the provision of health services and is often hampered by data problems, the difficulty of defining measurable objectives in a reliable and valid manner, and the challenge of capturing social determinants of health and community experiences.12-13 The WHO health systems strengthening framework, despite critique of its limitations, is useful in focusing attention on the performance of the health system by linking system building blocks, performance elements and overall outcomes, including population health status.8

An adaptation of the WHO framework is shown in Fig. 18 and consists of the following:

Health system building blocks. These include six building blocks of service delivery; human resources (health workforce); finances; medical products, vaccines and technology; information; and leadership and governance.

Health delivery platforms include the district health system; hospitals; and the private sector (both for-profit and non-profit organisations).

Health system performance includes equitable access, coverage, quality and safety.

System outcomes include improved health (level and distribution); social and financial risk protection; responsiveness; and improved efficiency.

Assessing the South African health system

System building blocks

The democratic SA government inherited a highly fragmented health system in 1994, with wide disparities in health spending and inequitable distribution of health care professionals. There were inequities in access to and quality of care between and within provinces; between black and white; between urban and rural areas; and between the public and private health sectors.3,6,14-16 Transformation efforts in the health sector spanning more than 15 years include numerous structural, legislative and policy changes, overcoming apartheid in health services, implementation of health programmes for priority conditions, and improvements in access to health care services.6,17 There have been numerous positive developments and improvements in the lives of South Africans since the country's democratic transition.15,18-19 However, urban/rural and public/private inequities remain acute, and are exacerbated by numerous health system challenges.19-22

An enabling legal and policy framework is in place, and there have been many areas of progress (Table I). At the same time, significant health system challenges for each of the six health system building blocks need to be addressed.10,20,22

Delivery platforms

Resources are being inequitably and inefficiently used in the SA health system. Specific examples of primary care, district and central hospitals follow.

Table II shows the district primary health care spending trends.23 The districts are categorised from highest to the lowest spending per capita. Paradoxically, from an equity perspective, some of the largest percentage increases occur in districts that are already spending higher than the average per capita.23 The data highlight the marked differences in spending on primary health care.

Fig. 2 shows the cost of keeping an average patient in a district hospital for one day, the patient-day equivalent (PDE), an indicator showing on average how much it costs for one patient to spend one day in the hospital. This figure illustrates the wide differences between districts, which conceal the even greater differences between individual hospitals. Even in the same province there is a wide range. For example, in the Eastern Cape the cost per PDE in Nelson Mandela Bay Metro is twice as high as in Chris Hani.24

As district hospitals consume over 40% of total district resources, the wide ranges in PDE are of great concern. Costs at the high end may indicate lack of efficiency or leakage out of the system, while costs at the low end may indicate poor quality of care.

Table III shows selected indicators in a sample of tertiary hospitals.22 Focusing on the cost per PDE indicates a wide range of potential inefficiencies in the system. Some central, academic hospitals in KwaZulu-Natal and the Free State are more expensive than those in the Western Cape and Gauteng, partly because the institutions are not working at optimal capacity.22

These differences point to poor monitoring and accountability at all levels of the system.

How healthy are South Africans?

Health outcomes in SA are poor and not commensurate with the level of health expenditure in the country. Scientists have described a quadruple burden of diseases in SA, comprising HIV and AIDS, poverty-related diseases, chronic diseases of lifestyle and high rates of injury.15,20,25

SA has an estimated 5.5 million people living with HIV, with an HIV prevalence of close to 30% of all public sector antenatal clinic attendees, and wide geographical differences.26 The rise of HIV prevalence has been followed relentlessly by a threefold increase in the incidence of tuberculosis (TB) from 1996 to 2006 (Fig. 3).27 Mortality statistics show an increase in deaths due to TB, from 13.1% of all deaths in 1997 to 25.5% in 2005, and deaths due to pneumonia increased from 4.8% in 1997 to 8.7% in 2005.28 These large increases are almost certainly due to the classification of AIDS-related illnesses into these categories.

After HIV and AIDS deaths (29.8%), cardiovascular disease (16.6%), infectious and parasitic diseases (10.3%), malignant neoplasms (7.5%), intentional injuries (7.0%) and unintentional injuries (5.4%) were the leading cause of death in 2000.25 Hence, noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) and injuries constitute a growing public health problem, which must be addressed at the same time as HIV and TB.29

Implications for DCP in South Africa

This assessment paints a picture of a society that is gripped by a complex disease burden: the twin epidemics of HIV and TB, coupled with non-communicable diseases and injuries. The health system is inordinately complex. Visible and decisive leadership is needed to contextualise and prioritise the interventions required to improve the health system and the health status of South Africans.22

Although considerable resources are being spent on health and there have been massive improvements in reducing inequitable spending, there are still large disparities exemplified by the per capita expenditure on non-hospital primary health care.23-24

Data from district hospitals point to large-scale inefficiencies among individual hospitals and also among different provinces. Costeffectiveness studies and interventions may improve the functioning of the health system in SA and get better value for money. However, key issues must be taken into account in any DCP initiative that is taken forward:

• The risk of emphasising selective interventions in health care delivery, inherent in the cost-effectiveness approach. Hence, any DCP project should take into account the complex disease burden and existing challenges in the health system, and aim to analyse the cost-effectiveness of integrated services.

• The technical complexity and enormous data inputs required for cost-effectiveness analyses. The project should ensure that due emphasis is placed both on building local capacity at universities, and on building capacity within government to utilise the information.

• The reality that budgeting and planning is not zero-based, i.e. future planning must take into account existing services and systems. Therefore the information gathered in the cost-effectiveness exercise must reflect the costs of adjusting the supply of a particular intervention upwards or downwards from its current level.

• The DCP should assist with the development of appropriate staffing models.

• The DCP should assist with discontinuation of health care interventions/activities that add no value to health outcomes.

• The DCP must recognise that society often places a disproportionate value on certain sorts of treatment, including expensive life-saving care. The approach should take into account public values and professional opinion and pay due attention to the context and processes of decision-making.

• Few developing countries have a comprehensive monitoring and evaluation system, existing systems suffer from lack of co-ordination and are often paper-based, and information generated has problems of quality, completeness, timeliness and duplication. The DCP should facilitate the development of a streamlined system, rather than exacerbate existing data requirements

• Lastly, the DCP should recognise that a technical approach to health sector priorities based on burden of disease and cost-effectiveness analysis should not be a rigid prescription for all health system ailments, but is only one input to the policy process.4

We would like to thank Professors Karen Hofman and Steve Tollman for their encouragement and support. This paper is based on a longer report entitled: 'Overview of health care and the health system in South Africa: Implications for the Disease Control Priorities (DCP) project', done as part of the launch of the Priority Cost Effective Lessons for Systems Strengthening (PRICELESS) South Africa initiative, August 2009. The report was funded by the Fogarty International Center at the US National Institutes of Health and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

1. World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2008: Primary Health Care, Now More Than Ever. Geneva: WHO, 2008. [ Links ]

2. Beaglehole R, Bonita R. Global public health: a score card. Lancet 2008;372:1988-1996. [ Links ]

3. Barron P, Roma-Reardon J, eds. South African Health Review 2008. Durban: Health Systems Trust, 2008. [ Links ]

4. Murray CJ, Kreuser J, Whang W. Cost-effectiveness analysis and policy choices: investing in health systems. Bull World Health Organ 1994;72:663-674. [ Links ]

5. Rispel L, Setswe G. Stewardship: Protecting the public's health. In: Harrison S, Bhana R, Ntuli A, eds. South African Health Review 2007. Durban: Health Systems Trust, 2007. [ Links ]

6. Schneider H, Barron P, Fonn S. The promise and practice of transformation in South Africa's health system. In: Buhlungu S, Daniel J, Southall R, Lutchman J, eds. State of the Nation: South Africa 2007. Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council, 2007. [ Links ]

7. World Health Organization. World Health Report 2000: Health Systems: Improving Performance. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2000. [ Links ]

8. World Health Organization. Everybody's Business. Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes: WHO's Framework for Action. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007. [ Links ]

9. Travis P, Bennett S, Haines A, et al. Overcoming health system constraints to achieve the Millenium Development Goals. Lancet 2004;364:900-906. [ Links ]

10. Department of Health. National Department of Health Strategic Plan 2010/11-2012/13. Pretoria: Department of Health, 2010. [ Links ]

11. Hoffman K. Scope and expectations of the South Africa Country Study. Paper presented at the launch workshop entitled 'Setting priorities for health: Crafting a South Africa-specific strategy', 10 - 12 August 2009, Mount Grace Country Hotel, Magaliesberg. [ Links ]

12. Loeb JM. The current state of performance measurement in health care. Int J Qual Health Care 2004;15:i5-i9. [ Links ]

13. Navarro V. The new conventional wisdom: An evaluation of the WHO report Health systems: Improving performance. Int J Health Serv 2001;31:23-33. [ Links ]

14. Chopra M, Lawn JE, Sanders D, et al. Achieving the health Millennium Development Goals for South Africa: challenges and priorities. Lancet 2009;374:1023-1031. [ Links ]

15. Coovadia H, Jewkes R, Barron P, Sanders D, McIntyre D. The health and health system of South Africa: historical roots of current public health. Lancet 2009;374:817-834. [ Links ]

16. Shisana O, Rehle T, Louw J, Zungu-Dirwayi M, Dana P, Rispel L. Public perceptions on national health insurance: Moving towards universal health coverage in South Africa. S Afr Med J 2006;96:814-818. [ Links ]

17. Health Systems Trust. South African Health Reviews. Durban: HST, 1995-2008. [ Links ]

18. Buhlungu S, Daniel J, Southall R, Lutchman J, eds. State of the Nation: South Africa 2007. Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council, 2007. [ Links ]

19. Statistics South Africa. Achieving a Better Life for All: Progress between Census 1996 and 2001. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa, 2005. [ Links ]

20. Development Bank of South Africa. Health Sector Roadmap. Johannesburg: DBSA, 2008. [ Links ]

21. Gilson L, McIntyre D. South Africa: The legacy of apartheid. In: Evans T, Whitehead M, Diderichsen F, Bhuiya A, Wirth M, eds. Challenging Inequities in Health: From Ethics to Action. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. [ Links ]

22. Integrated Support Teams. Review of Health Over-spending and Macro-assessment of the Public Health System in South Africa: Consolidated Report. Pretoria: ISTs, 2009. [ Links ]

23. Bletcher M, Day C, Dove S, Cairns R. Primary health care financing in the public sector. In: Barron P, Roma-Reardon J, eds. South African Health Review 2008. Durban: Health Systems Trust, 2008. [ Links ]

24. Day C, Barron B, Montecelli F, Sello E, eds. District Health Barometer 2007/8. Durban: Health Systems Trust, 2009. [ Links ]

25. Bradshaw D, Nannan N, Groenewald P, et al. Provincial mortality in South Africa 2000 - priority setting for now and a benchmark for the future. S Afr Med J 2005;95:496-503. [ Links ]

26. Department of Health. National HIV and Syphilis Antenatal Prevalence Survey, South Africa 2008. Pretoria: Department of Health, 2009. [ Links ]

27. Department of Health. Tuberculosis Strategic Plan for South Africa, 2007-2011. Pretoria: Department of Health, 2008. [ Links ]

28. Statistics South Africa. Mortality and Causes of Death in South Africa, 2003-2004. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa, 2006. [ Links ]

29. World Health Organization. 2008-2013 Action Plan for the Global Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008. [ Links ]

Laetitia Rispel is adjunct Professor in the Centre for Health Policy, School of Public Health, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, current President of the Public Health Association of South Africa (PHASA), and the principal investigator of a large research programme on Human Resources for Health (HRH). She was Executive Director of the Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS and Health Research Programme at the Human Sciences Research Council, and was head of the Gauteng provincial health department from 2001 until 2006.

Peter Barron is a medical doctor, public health specialist and previous accountant with more than 30 years of public health sector experience, both as a clinician and manager in local and provincial government. The main focus of his recent work has been around improving the quality of care at primary care level and implementation of a district health system in South Africa. He has published widely on immunisation, maternal and child health, district health, quality of care, health information systems and health service delivery.

Corresponding author: Laetitia Rispel (laetitia.rispel@wits.ac.za)