Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.100 n.10 Pretoria Oct. 2010

ORIGINAL ARTICLES

Mental health services funding and development in KwaZulu-Natal: a tale of inequity and neglect

Jonathan K Burns

MB ChB, MSc, FCPsych (SA). Department of Psychiatry, Nelson R Mandela School of Medicine, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Globally, a significant 'mental health gap' exists between the major burden of mental and substance use disorders and the provision of psychiatric and mental health services. As a signatory to the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, South Africa has committed itself to transformation aimed at ending the inequities that characterise mental health service provision and 'closing the gap'.

METHODOLOGY: Budget allocations over a 5-year period to 6 psychiatric and 7 general hospitals in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) are compared and current numbers of psychiatric beds and psychiatric personnel in that province are contrasted with the numbers required to comply with national norms.

RESULTS: The mean increase in budget allocations to public psychiatric hospitals was 3.8% per annum, while that to general hospitals over the same period was 10.2% per annum. The median cumulative budget increase for psychiatric hospitals was significantly lower than that of general hospitals (Mann-Whitney U-test, p=0.001). No psychiatric hospitals received specific funding for tertiary services development. KZN has 25% of the acute psychiatric beds and 25% of the psychiatrists required to comply with national norms, with the most serious shortages experienced in northern KZN. There are 0.38 psychiatrists per 100 000 population in KZN.

CONCLUSION: Inequitable funding, inadequate facilities and significant shortages of mental health professionals pervade the mental health and psychiatric services in KZN. There is little evidence of government abiding by its public commitments to redress the inequities that characterise mental health services.

It is estimated that 14% of the global burden of disease is attributable to neuropsychiatric disorders, with depressive illness, anxiety disorders, substance abuse and psychotic disorders contributing the greatest proportion.1 Over 30% of disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) are attributed to mental disorders which are expected to rise significantly over the next 2 decades.2,3 Co-morbidity with physical illness and substance abuse is common3,4 and individuals with mental disorders are at substantially higher risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes and reduced life expectancy.5 Of particular relevance to sub-Saharan Africa is the fact that, in the treatment of such conditions as HIV/AIDS and drug-resistant tuberculosis, the presence of co-morbid mental disorders is associated with high-risk behaviour, poor treatment adherence, and inability to access care.6

Nevertheless, in both high-income countries (HICs) and low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) world-wide, mental health care is a low priority, receiving stunted budgets, inadequate resources, and little attention from government.7 For example, mental health is notably absent from the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), even though mental illness impinges both directly and indirectly on many areas of social and economic life.8 Evidence links mental health directly to 3 of the MDGs - eradication of extreme poverty and hunger; reduction of child mortality; and improvement of maternal health.

Globally, mental health care receives a disproportionately small proportion of health budgets, and psychiatric services lag far behind other services in funding, infrastructure development, human resources and the provision of appropriate medical supplies and treatments.7 The discrepancy between mental health needs and mental health service provision is more extreme in LMICs, especially in Africa.9 The World Health Organization (WHO) MHGap programme is specifically aimed at encouraging governments and policy-makers to 'scale up' the provision of mental health services within LMICs.10 In most countries, mental health is forgotten and neglected in planning, strategising and budgeting for regional and national health services. Many countries have either outdated or no mental health legislation and, almost universally, mental health is not identified as a key health priority meriting specific planning and specific financing.11 Consequently, mental health is financed out of general health budgets and inevitably ends up at the bottom of a pile of pressing needs when money is allocated. This is especially the case in countries struggling with other major health problems such as HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis.

Mental health in South Africa

Despite South Africa's progressive mental health legislation (Mental Health Care Act 2002 (MHCA 2002)12), the same barriers to the financing and development of mental health services exist, which result in: (i) psychiatric hospitals remaining outdated, falling into disrepair, and often unfit for human use; (ii) serious shortages of mental health professionals; (iii) inability to develop vitally important tertiary level psychiatric services (such as child and adolescent services, psychogeriatric services, neuropsychiatric services, etc.); and (iv) community mental health and psychosocial rehabilitation services remaining undeveloped, so that patients end up institutionalised, without hope of rehabilitation back into their communities. This state of affairs remains unchanged despite the legislated commitments to reform mental health care in the MHCA (2002). In 2007, South Africa was a signatory to the United Nations' Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and its Optional Protocol13 which was ratified several months later. Accordingly, the South African Government committed itself to a radical new approach to persons with disabilities of all kinds (including mental disorders). This approach is based on the fundamental premise that such persons are 'subjects' with rights, who are capable of claiming those rights and making decisions for their lives based on their free and informed consent as well as being active members of society. This political decision has profound implications for health and social development agendas at all levels of government. Furthermore, the establishment of the international Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which has oversight and monitoring functions, means that citizens of signatory states (including South Africa) have a means of reporting local violations and obtaining redress.

Risk for mental illness in KZN province

Of the 9 provinces, KZN has factors that make it one of the most high-risk regions in South Africa for mental disorders: the highest proportion of people living beneath the poverty line,14 highest poverty gap,15 second-highest level of income inequality, third-highest unemployment rate,14 highest prevalence of HIV/AIDS16 and second-highest murder rate.17 All these are recognised risk factors for mental illness.18-22 While prevalence rates of mental disorders are not available for the various provinces, a comparison of suicide rates in 6 major cities of South Africa showed that eThekwini (Durban) in KZN had the second-highest rate for men.23 Data from the South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use (SACENDU) show that KZN has the fourth-highest prevalence of treated substance abuse.24

As South Africa, and KZN province in particular, has many environmental risk factors for mental disorders, it is important to investigate the state of psychiatric and mental health services to deal with the burden of mental disease. Is the South African government, through its provincial and district public health services, seriously pursuing the standards of mental health care provision it set itself in the MHCA (2002)? Is there evidence in terms of actual service delivery that its commitment to human rights for the mentally ill is more than just a signature on an international treaty? This study reports on the state of psychiatric services in KZN province, analyses relative state funding to psychiatric and general hospitals, and compares current figures of psychiatric hospital beds and human resources in psychiatry with national norms.25

Methodology

Hospital budgets

Annual budget allocations to general and psychiatric hospitals in KZN over a 5-year period were obtained from institutional finance managers, and percentage increases in annual budget allocations then calculated. The median cumulative budget increase for psychiatric hospitals was compared with that of general hospitals, and univariate analysis was performed using non-parametric methods (Mann-Whitney U-test) with the SPSS statistical package version 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago, USA). A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Hospital beds

The numbers of usable psychiatric beds in all district, regional and psychiatric hospitals in KZN ('existing beds') was obtained from institutional clinical heads, and categorised as 'acute', 'medium- to long-term' and 'forensic' beds. Population statistics were obtained from the online Stats SA database26 and, using national norms for psychiatric beds published by the National Department of Health (DoH),25 numbers of beds required (to comply with national norms) were calculated for the population of KZN (i.e. 'required beds'). Existing beds were then expressed as a percentage of required beds to establish the extent to which current services comply with national norms.

Human resources

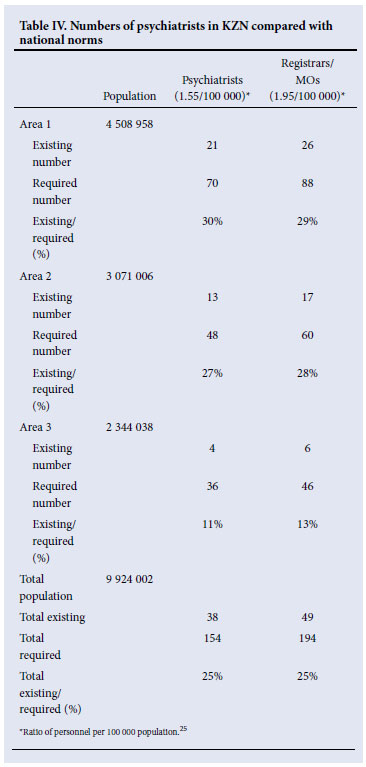

The author had access to a list of all psychiatrists as well as registrars and medical officers (in psychiatry) currently employed by the public health service in KZN (i.e. 'existing'). Population statistics were obtained from the online Stats SA database26 and, using national norms for psychiatric human resources published by the DoH,25 the numbers of psychiatrists and registrars/medical officers required (to comply with national norms) were calculated for the population of KZN (i.e. 'required'). Existing personnel were then expressed as a percentage of required personnel in each category of professional to establish the extent to which current psychiatric human resources complied with national norms.

Results

Budgetary information was obtained for 6 psychiatric hospitals and 7 general hospitals. Budget increases to psychiatric hospitals over the 5-year period ranged from 8% to 25%, with a mean 5-year increase of 19% and a mean annual increase of 3.8% (Table I). Budget increases to general hospitals over this period ranged from 29% to 64%, with a mean 5-year increase of 51% and a mean annual increase of 10.2% (Table II). The median cumulative budget increase for psychiatric hospitals was significantly lower than that of general hospitals (Mann-Whitney U, p=0.001). A drop in budget allocations at some point during the 5-year period was experienced by 4 of the 6 psychiatric hospitals surveyed, but none of the general hospitals experienced a drop in budget during the period. Specific funding for tertiary services development within their budgets (from the National Tertiary Services Development Grant - NTSDG) was received by 2 of the general hospitals, but no psychiatric hospitals received such allocations.

The analysis of current psychiatric beds in KZN revealed a marked shortage of acute beds (25%), a slight shortage of forensic beds (80%) and an oversupply of medium- to long-term beds (161%) in relation to the numbers required to comply with national norms25 (Table III). Broken down into the 3 health areas of KZN, Area 3 is by far the most deprived region (with only 6% of required acute beds, 41% of required medium- to long-term beds and no forensic beds).

There are currently a total of 38 psychiatrists in KZN's public health services - a ratio of 0.38 psychiatrists per 100 000 population and constituting 25% of the number of psychiatrists required to comply with national norms.25 There are only 49 registrars/medical officers working within public psychiatric services in the province, constituting 25% of the number required to comply with national norms (Table IV). Comparing the 3 health areas of KZN shows that area 3 is worst off, with only 11% of the required number of psychiatrists and 13% of the required number of registrars/medical officers.

Discussion

Inequitable funding to psychiatric hospitals

Psychiatric hospitals received on average a third of the budgetary increases received by general hospitals over the period surveyed, which illustrates a pattern of inequitable treatment of psychiatric hospitals in relation to general hospitals. While a comparison of the actual funding of institutions per bed per day (or on a 'patient day' basis) would not in itself be instructive (since bed costs vary according to disease profile and services rendered), a comparison of relative budgetary increases is informative. This is because the latter analysis more closely reflects the value attributed to the service by the funders than a simple comparison of daily bed payments (where multiple confounding factors need to be taken into account). The fact that two-thirds of the psychiatric hospitals surveyed experienced a drop in budget at some point in the 5-year period - which no general hospitals experienced - highlights the impression that government does not value psychiatric services and sacrifices the expansion of psychiatric services to maintaining general hospital services.

No funding to tertiary psychiatric services

Psychiatric hospitals receive no specific allocation from the conditional grant earmarked for the development of tertiary level services (the national tertiary services development grant (NTSDG)). Since all specialist disciplines (excepting psychiatry) locate their tertiary level services within general hospitals (in this case, Greys Hospital and Edendale Hospital), they benefit from 'ring-fenced' allocations in these hospitals for the development of their tertiary services. Psychiatry, however, is a 'stand-alone' service located in specialised psychiatric institutions, and the development of important tertiary level psychiatric services (such as child and adolescent psychiatry, neuropsychiatry and psychogeriatrics) within these institutions is not funded at all. Any advances in the development of tertiary psychiatric services occur only when clinicians manage to convince already cash-strapped institutional managers to overspend on their barely adequate 'equitable share' budgets. This unfair situation results in hospitals routinely overspending their annual budgets as they strive to improve service provision, thereby contributing to the ever growing overspend of the provincial Department of Health (currently approximately 6 billion rands over the last 3 financial years in KZN). The effects of this inequitable treatment of psychiatric services can be seen in the miserable state of tertiary psychiatric services in the province - there are a total of 4 in-patient child and adolescent beds; 10 dedicated psychogeriatric beds; 20 in-patient psychotherapy beds; and no dedicated beds for neuropsychiatry, dual diagnosis, firstepisode psychosis and eating disorders. In the light of the increasing prevalence of HIV-related neuropsychiatric disorders, the high levels of co-morbid substance abuse and the hidden epidemic of trauma-related psychopathology in both adults and children/adolescents that characterise KZN, this lack of specialised services is inexcusable.

Inadequate beds for psychiatric care

KZN has only a quarter of the acute beds required to comply with national norms of 28 beds per 100 000 population.25 Acute beds are required at district, regional and psychiatric hospitals, as the MHCA (2002) introduced a system whereby individuals with mental disorders should be treated at their nearest hospitals for at least the first 72 hours before transfer to a psychiatric hospital.27 The shortage of acute beds in KZN is felt most keenly in area 3 (northern KZN) and area 1 (Durban and South Coast), where long waiting-lists necessitate the daily transfer of patients to the better-resourced hospitals in area 2 (Midlands). In contrast, there is an excess of medium- to long-term beds in the province, especially in areas 1 and 2, owing to the historical practice of institutionalising many patients who should have been rehabilitated back into the community, a problem that is common to most national and international mental health systems. The relative lack of community-based mental health services constitutes a barrier to the success of psychosocial rehabilitation programmes in KZN aimed at achieving de-institutionalisation of long-term hospitalised patients. Although forensic psychiatry beds required for the observation of offenders referred from courts and for the care, treatment and rehabilitation of State patients are almost sufficient in terms of norms, they are almost entirely centralised in one institution. This situation creates major logistical problems, as KZN is geographically widespread with large rural regions. The lack of regionalised forensic services hinders the rehabilitation and follow-up of State patients released on conditional discharge, with obvious detrimental legal implications.

Shortage of mental health professionals

Public mental health services in KZN have only a quarter the number of psychiatrists and registrars/medical officers required by national norms. As most of these personnel are located in large urban areas, the more remote rural regions of the province are largely without psychiatric expertise. It is sobering to note that, even though KZN is so short of psychiatrists, it has the third-best ratio of psychiatrists to population (after the Western Cape and Gauteng).28 While there has been some success with recruiting psychiatrists to regionalised general hospitals (10 of 12 regional hospitals have at least one psychiatrist), many of these institutions have not made psychiatrist posts available on their post establishments, and in many cases individuals have been seconded from psychiatric hospitals to work at regional institutions. In terms of sub-specialist psychiatrists, there are only 2 forensic psychiatrists and 2 child and adolescent psychiatrists in the province, all of whom are located in the 2 major urban centres.

Conclusion and recommendations

Psychiatric and mental health services in KZN are historically and currently disadvantaged in terms of funding, infrastructure development and staffing. While acknowledging the major burden of infectious diseases, trauma and poverty-related health problems on the health services of the province, it appears that the burden of mental health disorders is not a priority for the provincial government and health department. Inequitable funding, inadequate facilities and significant shortages of mental health professionals characterise the mental health and psychiatric services, and obstruct efforts to develop and improve standards of, and access to, services for the mentally ill. In KZN province, there is little commitment from government to realising the laudable objectives of the MHCA (2002)12 and abiding by its subscription to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and its Optional Protocol.13

Recommendations to redress these inequities include:

• establishing a specific national and provincial funding mechanism for hospital-based and community-based mental health services development

• acknowledging and including internationally recognised tertiary level psychiatric sub-specialist services by government so that psychiatry is not discriminated against in funding for tertiary health services

• a commitment to redress the inequitable distribution of infrastructural and human resources in the health services so that psychiatric and mental health services 'catch up' to the government professed norms and standards

• practical efforts by government to implement transformation within psychiatric and mental health services so that its nationally and internationally stated commitments to their reform move beyond rhetoric and become a physical reality for those affected by mental disorders.

References

1. Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 2006;3:e442. [ Links ]

2. World Health Organization. Mental Health: Facing the Challenges, Building Solutions. Report from the WHO European Ministerial Conference. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2005. [ Links ]

3. Prince M, Patel V, Saxena S, et al. No health without mental health. Lancet 2007;370(9590):859-877. [ Links ]

4. Srinivasa Murthy R. Psychiatric comorbidity presents special challenges in developing countries. World Psychiatry 2004;3(1):28-30. [ Links ]

5. De Hert M, Dekker JM, Wood D, Kahl KG, Holt RI, Möller HJ. Cardiovascular disease and diabetes in people with severe mental illness position statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Psychiat 2009;24(6):412-424. [ Links ]

6. Jonsson G, Joska JA. Assessment and treatment of psychosis in people living with HIV/AIDS. S Afr J HIV Med 2009;35:20-27. [ Links ]

7. Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, Whiteford H. Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet 2007;370(9590):878-889. [ Links ]

8. Miranda JJ, Patel V. Achieving the millenium development goals: Does mental health play a role? PloS Med 2005;2(10):962-965. [ Links ]

9. Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, et al. The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull World Health Organ 2004;82(11):858-866. [ Links ]

10. Lancet Global Mental Health Group. Scale up services for mental disorders: A call for action. Lancet 2007;370(9594):1241-1252. [ Links ]

11. Mangalore R, Knapp M. Equity in mental health. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc 2006;15(4):260-266. [ Links ]

12. South African Government. Mental Health Care Act (2002) www.acts.co.za/mental_health_care_act_2002.htm (accessed 18 February 2010). [ Links ]

13. United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Optional Protocol. 2007; United Nations Enable. http://www.un.org/disabilities/default.asp?navid=13&pid=150 (accessed 18 February 2010). [ Links ]

14. South African Institute of Race Relations (SAIIR). Unemployment and Poverty. 2008. http://www.sairr.org.za/sairr-today/news_item.2008-11-28.9488661622 (accessed 18 February 2010). [ Links ]

15. Human Sciences Research Council. Fact sheet: Poverty in South Africa. 2004. http://www.sarpn.org.za/documents/d0000990/P1096-Fact_Sheet_No_1_Poverty.pdf (accessed 18 February 2010). [ Links ]

16. Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, et al. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence Behaviour and Communication Survey 2008: A Turning Tide among Teenagers? Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2009. [ Links ]

17. Institute for Security Studies. Murder in the RSA for April to March 2003/2004 to 2008/2009. http://www.iss.co.za/index.php?link_id=24&slink_id=8298&link_type=12&slink_type=12&tmpl_id=3 (accessed 18 February 2010). [ Links ]

18. Patel V, Kleinman A. Poverty and common mental disorders in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ 2003;81(8):609-615. [ Links ]

19. Weich S, Lewis G, Jenkins SP. Income inequality and the prevalence of common mental disorders in Britain. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:222-227. [ Links ]

20. Marwaha S, Johnson S. Schizophrenia and employment. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2004;39:337-349. [ Links ]

21. Vlassova N, Angelino AF, Treisman GJ. Update on mental health issues in patients with HIV infection. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2009;11(2):163-169. [ Links ]

22. Ribeiro WS, Andreoli SB, Ferri CP, Prince M, Mari JJ. Exposure to violence and mental health problems in low and middle-income countries: a literature review. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 2009;(Suppl 2):S49-57. [ Links ]

23. Burrows S, Leflamme L. Suicide mortality in South Africa: a city-level comparison across socio-demographic groups. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2006;41:108-114. [ Links ]

24. SACENDU. Update: Alcohol and drug abuse trends: January - June 2009. http://www.sahealthinfo.org/admodule/sacendunov2009.pdf (accessed 18 February 2010. [ Links ])

25. Norms Manual for Severe Psychiatric Conditions. Pretoria: National Department of Health, 2003. [ Links ]

26. Statistics South Africa. StatsOnline. http://www.statssa.gov.za/census01/html (accessed 18 February 2010). [ Links ]

27. Burns JK. Implementation of the Mental Health Care Act (2002) at district hospitals in South Africa: Translating principles into practice. S Afr Med J 2008;98:46-49. [ Links ]

28. Lund C, Kleintjies S, Kakuma R, et al. Public sector mental health systems in South Africa: inter-provincial comparisons and policy implications. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2010;45(3):393-404. [ Links ]

Accepted 2 March 2010.

Corresponding author: J K Burns (burns@ukzn.ac.za)