Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.100 n.9 Pretoria Sep. 2010

IZINDABA

Haiti tragedy shakes up SA's emergency response planning

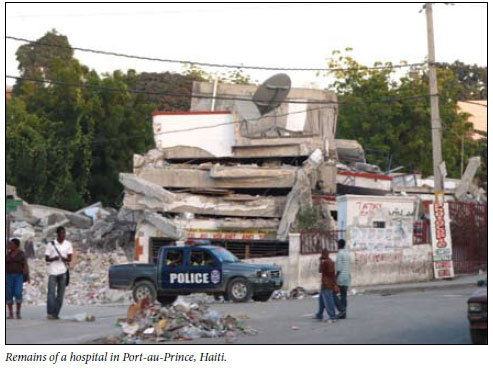

The tragic Haitian earthquake that claimed at least a quarter of a million lives this January and devastated that island has provided a sobering wake-up call for volunteer South African emergency medics who pitched in to help. South Africa's response was fragmented, with two NGOs operatingseparatelyandindependently.The lessons learnt have led to a joint initiative between the largest emergency academic medicine divisions in the country.

Six of South African's top disaster and emergency medics propose creating a single, all-inclusive, cross-sector, multi-disciplinary medical team that is properly trained, equipped and prepared to respond to local and international disasters.

The main weaknesses identified in South Africa's bid to help Haitians were the use of commercial flights, limiting the timely arrival of essential tools (including medical oxygen not being permitted on such flights), the lack of pre-departure briefings, no emergency evacuation plan or formal trauma debriefing sessions, and inappropriate food and clothing.

The experts insist that a prerequisite for 'deploy-ability' to any disaster area in future is that all volunteers complete the new International Search and Rescue Advisory Group (INSARAG) course. The group, who penned an original article for the August edition of the SAMJ ('Haiti: The South African perspective'),1 consists of some of the country's most respected and experienced working emergency medics. They question the efficacy of responding to disasters 'halfway across the world', arguing that as a developing country South Africa's contribution to settings such as Haiti, where the 12 January earthquake left 1.1 million homeless and 300 000 severely injured, was 'often miniscule when compared with that of Western countries'.

'Travelling for up to 5 days halfway around the globe to provide 3 days of assistance does not do justice to the commitment of resources and the dedication of the people involved,' they conclude. The authors believe the primary responsibility of local medics is to their fellow citizens, followed by the South African Development Community (SADC) countries and the rest of the African continent.

An example of First-World capability was the USA's navy hospital ship, Comfort, anchoring in Port-au-Prince within a week of the disaster to provide tertiary care via 1 000 beds, 75 ICUs and more than 1 000 on-board physicians and support staff. This multiplied the ability of on-shore agencies to manage minimally to moderately injured patients - and saved hundreds of extra lives.2 Comfort treated over 430 severely injured patients.

The 7.0 magnitude earthquake saw the world's largest humanitarian effort in over 6 decades.

What's really needed

The South African NGO outfits had minimal contact with one another and medics struggled on site, with INSARAG guidelines not fully followed. The expert South African group identifies future 'essential functional deployment categories' as the following: urban search and rescue; triage and initial stabilisation; and definitive medical care.

Four 'critical' components were needed to achieve this: rapid deployment; intelligence from the site; government facilitation; and working under recognised organisations such as the United Nations and the World Health Organization.

The emergency medicine divisions at the universities of the Witwatersrand, Stellenbosch and Cape Town will provide the structure for the new local multi-disciplinary medical response team. The intention is to work closely with all stakeholders.

Dr Fathima Docrat was among those in the Gift of the Givers NGO team who, together with the NGO Rescue South Africa, went to Haiti.

In a paper in the SAMJ3 she speaks of how ill-prepared she was for the dangers her team of 11 medics faced. These included infectious diseases, aftershocks and looting. Arriving with limited support, communication and supplies, she said it was 'hard not to think of ourselves as just extra mouths to feed, using precious resources like fuel, water and food that would be better utilised by the victims'.

It had also not been easy to reintegrate back into society when she returned home because 'one cannot begin to describe the events and emotions we felt ... it's difficult to explain the actual scale of the disaster ... it was simply overwhelming'. 'I don't think the human brain can comprehend such a mass casualty and the reactions of the victims,' Docrat added. Her colleagues were exposed to stressors similar to those of the victims, yet nobody was debriefed or made the effort to do so.

Emergency physician specialist Dr Daniël van Hoving (a Tygerberg Hospital clinician and Cape Metro EMS doctor), said what struck him most forcibly was that 'I wasn't prepared enough to go there'.

'The scale caught us out. You're not working with people you know every day - yet you have to trust your life to them. It showed me that there are systems far worse off than our own, in spite of all our moaning and groaning. They had virtually nothing to start with in terms of infrastructure and absolutely nothing after the quake,' he added.

Dr Wayne Smith, Western Cape emergency services co-ordinator for the 2010 World Cup and provincial disaster medicine chief, helped distil the lessons learnt in Haiti. He said response teams needed to 'leave nothing to chance' in their preparations. 'When someone says get a team together, you don't want to be casting around for who has vaccinations or passports or hastily drawing up replacement roster lists at work,' he stressed.

Horses for courses

The team skill-set needed to be such that if amputations were needed, the team included anaesthetists and surgeons while the response needed structuring into 'immediate phase', emergency medicine, and rehabilitation (wound cleaning, etc.), followed by primary health care. Neither NGO had surgeons or anaesthetists in Haiti.

Failure to meet these bare minimum criteria could create ineffectual 'disaster response tourist teams', with accompanying media resulting in the operation becoming little more than a PR exercise.

Asked why a single response team was only now being planned - after major disaster medicine preparations for the World Cup - Smith said the World Cup helped to break down traditional inter-provincial health care barriers, setting the scene for the new initiative. While Gauteng and the Western Cape were the two main 'response agencies' driving emergency medicine in South Africa (via university chairs of EM), all provinces had progressively pitched in to help one another.

National government had provided much of the 'heavy duty' equipment for search and rescue and disaster response, improving provincial services substantially just before and since the FIFA World Cup. Smith says he was 'very vocal' before the World Cup about not importing 'Korean, Japanese or German' solutions (previous World Cup host countries) to Africa. 'We applied our minds and used the best science to develop an African model of doing things and it worked really well. There's so much happening on our continent alone where we can be relevant and make a big impact,' he stressed. In Third-World countries the 'staff, stuff and systems' needed to be based on 'realism and not huge budgets,' he added.

Whether it was xenophobic attacks or a cholera outbreak, a new single medical response capability would be ideal locally, with the Western Cape now equipped with a mobile 8-bed ICU that could be set up the moment it arrived at its destination.

Smith said major incidents took place daily around the world, 'so I'm not saying get me on an international flight to save the world. What I'm saying is get us on a Dakota and fly me to an African state - we need to rather pull our continent together,' Smith added.

Looking out for our own first

He illustrated his point about local allegiance being paramount and the need for backup duty rosters in EMS control rooms by citing a tornado that struck Manenberg on the Cape Flats on 29 August 1999 - the day before his best medics were due to fly out and help with an earthquake that had devastated parts of Turkey a fortnight earlier. 'Needless to say we didn't go, but it does make the point,' he added.

If he received a call for help from a colleague in Johannesburg, 'say a massive sinkhole tragedy or cholera outbreak', one priority would be to ensure there was an inter-provincial 'memo of understanding' so his staff would be covered 'for all the bureaucratic nonsense'. These included local responsibilities in absentia, workmen's compensation claims and many other details 'needing sign-off so we can sort it out later', with political buy-in across provincial boundaries essential for success.

The national disaster centre in Gauteng currently relied on two specialised urban search and rescue teams (there and in the Western Cape).

A spokesman for Gift of the Givers was unavailable for comment.

Chris Bateman

1. Van Hoving DJ, Smith WP, Kramer EB, De Vries S, Docrat F, Wallis LA. S Afr Med J 2010;100:513-515. [ Links ]

2. Amundson D, Dadekian MS, Mill E, et al. Practising internal medicine onboard the USNS COMFORT in the aftermath of the Haitian earthquake. Ann Intern Med 2010;52(11):733-737. [ Links ]

3. Docrat F. S Afr Med J 2010;100:498. [ Links ]