Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versão impressa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.99 no.12 Pretoria Dez. 2009

IZINDABA

NHI will drive costs down – Shisana

Chris Bateman

The National Health Insurance Plan (NHI), due for legislation in June next year, will be phased in one facility at a time over the next 5 years, costing higher-income earners more (via a payroll tax) but in no way limiting their choice of provider.

That was the assurance given by the chair of the NHI Ministerial Advisory Committee, Dr Olive Shisana, who said the incremental accreditation of health care facilities was to ensure the delivery of quality health care based on agreed standards.

'If this quality improvement plan was implemented at one district or province at a time, I'd be worried, but the plan is to build capacity, facility by facility. When each facility (public or private) is ready and meets standards of accreditation, it gets declared NHI-ready and changes its modus operandi,' she explained.

The Ministerial Advisory Committee of 24 experts drawn from the entire health care spectrum is required to deliver advice to the draft proposals on NHI legislation to Health Minister Dr Aaron Motsoaledi by June next year. Public input will happen as soon as cabinet approves the policy proposals, so that the ensuing and legally required 3-month consultation process can be completed in time for Motsoaledi's review. That would leave just enough time for legal crafting for presentation to Parliament by June.

Shisana was responding to claims that the ANC government was 'overcompensating for apartheid health inequities in the form of a grand gesture' that was doomed to failure because of the woeful current state of public health care.

Critics of the NHI proposal, still in its raw, unrefined stages, say it is financially unsustainable because of the low population tax base, is being implemented with 'undue haste' (over 5 years) and will accelerate the loss of health care professionals, especially in the 'threatened' private sector.

The proposals as they stand create a central NHI funding and administration body, separate from the health department (but reporting to the Minister of Health) to oversee a fund estimated at R150 billion, promoting cross-subsidisation between rich and poor, healthy and sick, young and old.

Some economists believed that the new NHI would legally prevent medical aids from offering any benefits already offered by state facilities, but Shisana refuted this.

'The policy proposals do not place restrictions on type of services to be provided by private facilities. Nor will it restrict people to use the public or private sectors. What is certain is that contribution to NHI will be mandatory for those who meet specific income levels; once they have contributed they may if they so wish continue paying for medical aid and get services that are also provided or not provided in the publicly funded NHI services,' she told Izindaba.

Shisana said that the NHI was 'not just about funding' (Treasury have upped their health contribution from R65 billion to R89 billion to prepare for implementation of NHI), but also the provision of quality health services and the pooling of resources.

An ambitious public health sector revamping programme was being guided by Health Minister Dr Aaron Motsoaledi to bring more health care workers on line, improve drug availability, reduce theft, inefficiency and corruption, and overhaul facility management.

Shisana said facilities would be prepared for 'NHI readiness and accreditation', with the population served by each registered facility to ensure services were appropriate and in line with the NHI package on offer. The prices included in those services (through capitation) would be negotiated with each provider with money available directly from the NHI fund to pay for them. Until a facility was accredited it would continue operating as usual. 'To me it's very clear that this is all incremental so it can be sustainable. We've never favoured the big bang approach which so many of our critics accuse us of,' she said.

She said the Ministry's national public sector quality improvement plan was using the best local and international skills available. The NHI was 'not as ambitious as people say'. South Africa had the basis for introducing NHI; it had already introduced universal access to primary health care, a revised essential drug list was being completed 'as we speak', there was a plan to increase the number of health care providers and retain existing ones, and facility management was being interrogated to ensure 'the right people and competencies are there'. 'These are the building blocks of NHI. If somebody asked me have we started implementing NHI, I'd say yes we have started with the NHI building blocks,' Shisana said.

Public sector in for shock regulation

She took pains to emphasise that 'for the first time ever' there would be regulation of the public sector. 'In the past the government has regulated the private sector, not the public. The NHI will change that. We're saying the public sector (and private) have to meet these standards or criteria in order to become a member of the NHI. The state was never regulated in terms of public service delivery; perhaps that's why in some facilities they've had such a lousy quality of service!'

She stressed that the health needs of a geographical area would be pivotal in determining whether any facility would be accredited or not and advised prospective applicants that the NHI Ministerial Advisory Team will have access to top-quality research about the health needs of every health district in the country to inform planning. 'The question is not which sector (public or private) is delivering services there but what are the needs? For example there's no reason not to include GPs practising in small towns.' In areas with large populations she indicated that 'people should have a choice'.

'Our research indicates very clearly that people will not support the NHI if they don't have a choice of provider – they should be given that. So there must be public and private sector facilities in the vicinity but they can't be so close that they overlap. A person must be willing to drive or use public transport a few kilometres away to get the services he/she wants.'

NHI grass 'not greener' on other side

We asked Shisana to respond to fears that an NHI would lead to the collapse of the private sector and significant emigration of both principal members of medical schemes and specialists, thus destroying any chance of a viable system of universal access.

She said specialists were already leaving for countries with NHI systems (Canada, Europe and Australia – the USA is arguably headed towards an NHI).

'Why run away from a brand of NHI that you can have a hand in developing and participating in? It doesn't make sense to me, it's not logical. Rather tell us (her task team) that to keep doctors happy you must do X, Y and Z. And in any case many doctors go to work overseas temporarily and do come back,' she said.

The intense health economics debate around the NHI's proposed payroll and medical aids tax, based on StatsSA figures that 25% of South Africans are unemployed, thus of necessity 'punishing' higher-income earners, bewilders Shisana.

'When we produce our proposals in detail those who complain so vociferously will see that it's not monstrous, but is comprehensive and adequate. The reason they're expecting it to be unaffordable is because medical schemes are charging such exorbitant premiums. Part of that money obtained from premiums is used to buy luxury cars and pay bonuses of millions of rands per year. Some of these increase premiums so as to keep high perks while the members of schemes struggle to pay premiums.'

At the core of the NHI debate were 'questions of private interests versus public interest'. 'That is the debate on costs. They say 'you mean we're going to pay for those who're not going to pay! As if there's any person in SA who doesn't pay tax. I'm referring to VAT and for some petrol which are part and parcel of the revenue the state is collecting. We all have a responsibility to take care of the poor. Right now they cannot climb the ladder, often because they can't afford basic health care.'

Over-servicing 'rampant' in private sector

Shisana said over-servicing was rampant in the private sector and so-called expert opinions that NHI benefits would equal about a quarter of those currently available to medical scheme members, conveniently ignored this.

'Look at C-sections. Far too many are done during the week. And what do they do over weekends? Some bring in cancer patients to occupy beds and generate money while they're gone. We will propose how to cut unnecessary costs in order to deliver good affordable services. To think the state will simply take private sector mode of service delivery as they are and apply them to the whole population is the wrong way of thinking about costing. It's all about cost containment.'

She said the payroll levy would depend on 'how much the finance ministry allocates to health', but declined to name a figure, adding: 'remember that it is crucial to negotiate costs with hospitals, doctors and nurses in both sectors before finalising costing. Preliminary estimates have been made but we must examine them in light of negotiations and discussions with service providers. Pronouncing now about costs would be counter-productive.'

Shisana enthusiastically compared future NHI efficiency to the South African Revenue Services (SARS), arguably the most efficient government department in this country's history. The SARS model delivered quality service with administration costs well below 3% of what they collected.

Many medical aids 'headed for collapse anyway'

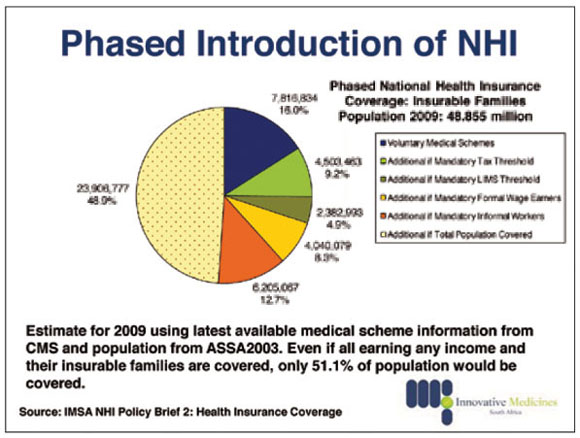

With 7.8 million South Africans on medical aid, many other schemes were 'headed for collapse' because they ran unsustainable financing models.

She cited evidence to the Parliamentary Portfolio Committee on Health in September that 18 schemes already reaching insolvency levels were advised by the Council for Medical Schemes to 'either merge or close shop'.

'Regardless of the NHI, if private sector medical schemes premium increases continue at this rate they'll become non-existent anyway,' she contended.

The NHI would actually protect the 7.8 million people on medical aid, preventing them from draining resources in the overburdened public sector when their insurance lapsed or savings schemes ran dry. The NHI would only pay for contracted service providers, be they private or public.

Doctors in this country were 'very good and we would love to keep them, so they must come up with suggestions on a system helping us all'. Doctor shortages, over and above increased intake in medical schools, would be dealt with via country-to-country agreements and red tape needed cutting to make it easier for any foreign-qualified doctor to work in South Africa.

Shisana's advice to private doctors

Asked where GPs would fit in the new set-up, Shisana replied: 'They will be encouraged to join the NHI and work in group practice. This does not mean that they must work with another doctor. The desired NHI model will be a team that includes nurses, counsellors, and so forth, depending on the disease profile. For example, if a practice setting includes a high HIV area, it will be critical to have counsellors to provide voluntary counselling. Working as a solo GP might not work well at all. GPs will be encouraged to build teams that will provide care required under the package of services. Payment will be based on capitation, the rates will surely have to be negotiated.

Shisana appealed to everyone to 'help this country end this unacceptable inequity. We ended apartheid but we didn't end health apartheid; it continues along the lines of who has money and who doesn't. If we're to thrive in future we need a healthy population, rich and poor. We need all to make a contribution. We can't do it with one population ill and poor and another rich and healthy'.