Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versão impressa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.99 no.8 Pretoria Ago. 2009

IZINDABA

Up to its eyeballs in sewage – government pleads for help

Chris Bateman

South Africa is sitting on a health time bomb caused by outright neglect of its water and sanitation systems – one that public health experts agree could lead to an epidemiological nightmare.

A full 85% of the country's sewage system infrastructure is 'dilapidated' and the overall neglect of the country's water and sanitation systems will cost R56 billion to repair, a comprehensive government-commissioned audit has found.

To give some idea of the potential impact of this on health care-related spending: it is R4 billion more than one cost projection for the health department's 2007 HIV plan to treat 80% of those who need ARVs by 2011.

Gauteng and the Western Cape are the only two provinces that largely comply with all three normative criteria of operations and maintenance, adequate water reticulation and drinking water quality. In spite of this, water and sanitation-related disease data submitted to the Human Rights Commission by an NGO coalition in mid-June show an increase in gastroenteritis admissions to Red Cross War Memorial Children's Hospital in the Cape Metropole of 37% (between 2001 and 2008), most of them from informal settlements where just over half of homes had piped water by 2007. Diarrhoea is the country's number one killer of children.

The national audit found Mpumalanga to be the most sickening province, with all 31 of the 50 municipalities for which data were obtained exceeding a maximum cumulative risk rating score of 7 or more, the bulk of them double or more this figure. Unsurprisingly, cholera managed to get into Mpumalanga's reticulated water supplies (Delmas) during the outbreak that spread from Zimbabwe and Limpopo between October last year and this February. Usually only faecal contamination of surface water used for drinking causes cholera outbreaks.

All 72 of the Northern Cape's municipalities and all of North West province's dozen municipalities scored on average double or more the maximum cumulative risk score.

The risk score is a combination of ratings on infrastructure design capacity and its adequacy, an effluent failure rating and technical skills of staff (where they exist).

The 2008/2009 'status quo assessment', by specialist auditors Aurecon, was commissioned in February by Sicelo Shiceko, Minister of Co-operative Governance (formerly Provincial and Local Government).

Afrikaner business began the shovelling

Ministry spokesperson, Ms Vuyelwa Vika, said Shiceko ordered the audit after the Afrikaanse Handelsinstituut (AHI) approached him in December last year, offering to help address problems profoundly impacting their members in several towns.

After studying the findings, Deputy Director-General in the department, Mr Elroy Africa, hurriedly began facilitating meetings with the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry (DWAF), the four main banks, NGOs and the private sector to develop a crisis strategy.

Vika emphasised 'Government can't address these deficiencies on its own'.

At the bottom of the cesspit in the findings was Mpumalanga's waste water treatment works (WWTW) at Morgenzon in the Dipaleseng Municipality, scoring a vile 39 (more than 5 times acceptable risk levels), while in the North West, the Taung WWTW in the Greater Taung Municipality ranked second – at 33.

The country's third most foul WWTW was Grootvlei Eskom, also in Mpumalanga's Dipaleseng municipality, posing a risk level of 32.

Health time bomb

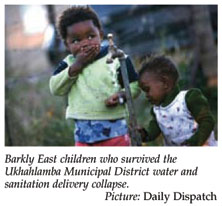

To give some idea of the health time bomb the new data represent (and almost certainly significant hidden mortality), the Ukhahlamba district municipality in Barkly East (Eastern Cape) scored 14 on the cumulative risk rating (twice the acceptable risk levels).

From January to April 2008, more than 80 Ukhahlamba children died of diarrhoeal diseases amid initial official denial, avoidance and obfuscation about a malfunctioning and decaying water reticulation and purification system.1

An epidemiological report confirmed that the purification process broke down in October 2007, with water tests revealing elevated levels of bacteria and Escherichia coli from then right through until March 2008. The first 15 Barkly East deaths led to a January report, tabled at a closed Ukhahlamba council meeting, recommending the situation be declared an emergency with a wider probe needed. This led to the grim discovery that the baby and child death toll at nearby Sterkspruit was 4 times worse (62 child or baby deaths).

The report found that the Barkly East chlorine pump had broken down and that when chemicals were added by hand the water was so dirty that they had little effect.

Only 2 of 7 boreholes were found to be working and a major pipe was 'exposed' in Zinyoka township, causing reservoirs to run dry.

The system was only inspected 5 months after a worried Barkly East money lender contacted an official to report an unprecedented number of grandmothers arriving at her office seeking loans to pay for baby funerals.

A concurrent lack of mobile clinics and medication in the local district hospitals aggravated the situation as medical staff found themselves helpless to effectively combat the unheralded epidemic.

The Aurecon water and sanitation audit said maintenance and refurbishment of all infrastructure, both bulk and reticulation, had been ignored in favour of capital investment in new infrastructure for providing basic services over the past 14 years.

Professor Leslie London, Director of the School of Public Health and Family Medicine at the University of Cape Town, said the findings illustrated how important it was to think of health systems as requiring the input and co-ordination of multiple sectors. Professor David Sanders, former head of Public Health Programmes at the University of the Western Cape, said the 'frightening' audit failed to mention the wider context of the 'appalling' lack of water and sanitation provision over the last decade and ignored deep rural areas. 'Provision has actually gone backwards,' he emphasised.

Both men agreed that the situation could lead to an 'epidemiological nightmare', with London saying that it would severely disrupt other health programmes and overload services struggling to cope with the existing burden of disease, especially HIV, and 'take a long time to turn around'.

Replace 90% of water treatment works – report

The audit found that, while waste water treatment works dilapidation had reached 85% nationally, the decay of water works treating bulk water supplies from dams and rivers stood at 90%, with both systems deemed to have 'a limited remaining useful life'.

Sewerage systems in Gauteng were operating at 102% (of design capacity), and there were still 224 264 households there waiting to be linked to the system.

The adequacy of water pipes to provide individual stands with water (i.e. reticulation) stood at only 68% in the Eastern Cape, while Gauteng (98%), Northern Cape (94%) and Mpumalanga (90%) were the only three provinces above 90%.

Drinking water quality was unacceptable in KwaZulu-Natal, Mpumalanga, North West and the Northern Cape, while all provinces had unacceptably high water losses owing to leakages. Water resources in most provinces were stretched and Limpopo, North West and Northern Cape had exploited theirs fully.

In spite of this, water losses in all municipalities were 'unacceptably' higher than 25%. (The acceptable international water loss standard is between 10% and 15%.)

Limpopo has the worst sanitation reticulation level at just 34%.

Chief among the reasons identified for the current crisis were a lack of planning and budgeting by councillors, the awarding of contracts to inexperienced contractors, lack of skilled officials to operate facilities, inability of officials to budget for and operate infrastructure, vacant managerial and operational posts, lack of technical ability to plan and manage capital-intensive water services projects, mostly unqualified controllers, lack of financial skills, and poor money management.

Dr Danie Wium, head of Aurecon's water division, told Izindaba that 'a confluence of situations' led to the existing mess. 'Old equipment should have been replaced and the other aspect is that there needs to be urgent consolidation and realignment of responsibilities for this thing going from national to local government.'

The report recommends a short-term strategy of establishing a joint task team to rescue those municipalities identified as critical and to classify others according to service delivery failure, institutional capacity, budget spend and operations and maintenance budget.

Getting on with it

Aurecon recommended that a final list of those municipalities requiring immediate intervention, backed by a plan of action, should be handed to the relevant minister 'within 2 weeks' and then implemented.

Speaking nearly 3 months after the report was completed, Vika would only say that her department was 'acting on this'.

Pressed on how deeply the health department was involved, she said that 'for now' Mr Africa's priority was facilitating strategic partnerships to address those issues identified.

However, her department and the DWAF worked with the health department 'whenever you have incidents like those babies dying and it comes to everyone's attention'.

Explaining the genesis of the audit, she said Shiceko 'opened the door to work with the AHI' in January. Pilot studies began on municipalities that were 'very critical' at Marble Hall (Mpumalanga), Okoukama (near Jeffrey's Bay in the Eastern Cape) and Emfuleni (Gauteng).

When the minister took this initial pilot report to Parliament 'complaints came in from all directions', so he commissioned the Aurecon audit to 'get to the root cause and determine how much government would need to deal with the problem overall'.

Professor Sanders said sanitation provision had worsened in Africa over the past decade and South Africa was a microcosm of this. Diarrhoeal and other sanitation-related diseases were unlikely to be overcome or controlled until sanitation, water and hygiene issues were properly dealt with.

'It becomes really frightening when you look at Cape Town (the Red Cross Children's Hospital data) where services are, by comparison (with municipalities cited in the report), excellent,' he added.

1. Bateman C. Incompetent maintenance/inept response – eighty more Eastern-Cape babies die. SAMJ 2008; 98: 429-430. [ Links ]