Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versão impressa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.99 no.5 Pretoria Mai. 2009

IZINDABA

Qualified ethics nod to doctors downing tools

Chris Bateman

Two top medical ethicists have given a qualified nod to doctors downing tools.

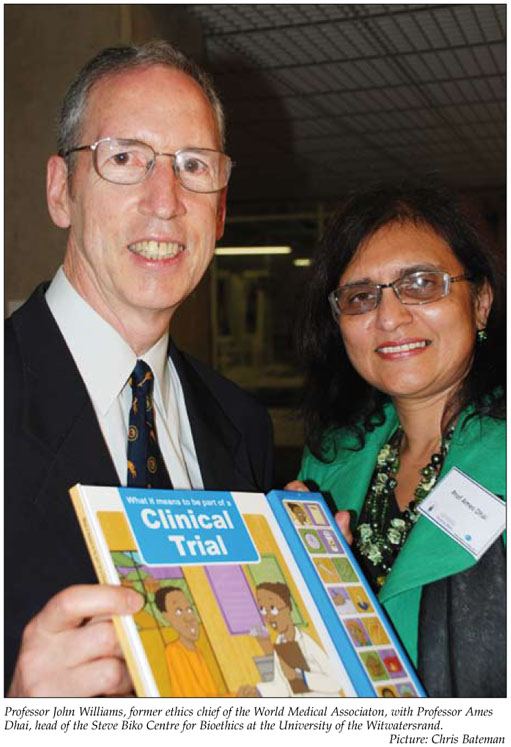

Professor John Williams, former head of the World Medical Association Ethics Unit, and Professor Ames Dhai, head of the Steve Biko Centre for Bioethics at the University of the Witwatersrand, were speaking at a forum on 'Ethics and professional practice in a resource-constrained environment'.

The burning issue arose during the Steve Biko Centre's acclaimed 'Ethics alive' week from 16 to 20 March this year in which students, seasoned physicians, academics and top legal experts thrashed out topical, historical and potential future problems.

Professor Martin Smith, Head of Surgery at Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital, put it to (topic presenter) Williams that he was 'right now sitting with two letters on my desk insisting we withdraw services because of resource constraints'. 'We're suffering because we never close our doors (to patients). What about a clinician withdrawing services to achieve better patient care?' he asked. Williams, currently Adjunct Professor of Medicine at Ottawa University, said that in several countries physicians had gone on strike for the good of patients when it was felt to be 'the only way of getting the attention of decision makers to bring about change'.

Downing tools can help patients in long run

The tactic of withdrawing services was controversial both in and out of the profession, with some arguing that it should never be done and others taking the 'longer view' that it would help the majority of patients in the long run. 'Some say that it's justifiable to inconvenience some in the short term. It's a matter of deliberation and judgment – but there must be a realistic expectation that it will have the desired effect. It needs groundwork, behind-the-doors discussion with friendly politicians, that if we do this you'll respond favourably,' he warned.

The danger was that if physicians had 'no idea of potential success', it could prove counter-productive, losing the support of decision makers, the public and patients who'd see the inconvenience as 'something unjustified'. Williams added, 'I would say in some cases it's justified but it very much depends on the circumstances. What's required is to weigh up the circumstances to see whether the prospects of success are worth the effort.'

Professor Dhai said she believed it was a question of 'looking at the lesser of two evils'. 'If resource constraints lead to faulty equipment with the possibility of loss of life of patients – our physicians are faced with this all the time – which is the lesser evil? Do you go ahead and do surgery and risk loss of life or down tools and use this as a bargaining situation with advocacy to get better support? I don't think one can make a blanket condemnation of the downing of tools,' she said.

Smith revealed that his department had run a single CT scanner for several weeks recently, with his neurosurgeons telling him they could no longer see emergency patients. Patients were getting woefully inadequate treatment. 'Basically our neurosurgeons said that if it (the second CT scanner) was not fixed within a certain time they'd refuse to see patients,' Smith added.

Pressed on what doctors should do when faced with loyalty to proper clinical care versus the administrative processes that so often bedevil it, Deputy Director General of Health, Dr Kamy Chetty, stressed 'reasonable procedure'. She said, 'The question really is what are some of the procedures that you'd use to voice those concerns? In different facilities you may have different individuals who raise various concerns there can be opportunism it's extremely important to agree on how these things get raised.'

Health Deputy DG: 'Always ask us first'

Chetty said she appreciated that the normal channels of communication were not always necessarily open and 'where necessary actions are not being taken'. 'As professionals we have to ensure that we get correct procedures and policies for our patients. If that fails we need to agree as to what the strategy is thereafter – at no time can we say that this was not brought to the attention of the authorities,' she stressed.

George Bizos, celebrated human rights lawyer, said strong legal precedent existed in South Africa, 'where the will of the practitioners has trumped contrary policy positions and given relief to people. Medical independence is generally respected by the courts in terms of our constitution and legislation, and particularly the common law.'

He gave an example of where a hospital stopped giving an AIDS patient newly available medication after six months because it was no longer available free of charge. The patient, backed by his doctors, took the case to court and won, with the court ruling that 'you can't treat an individual in terms of general policy'.

Chetty said she accepted that when it came to loyalty to the employer versus the patient, 'the patient comes first', but qualified this. In a resource-constrained environment the State had a responsibility to help as many people as possible.

'So we draft policies in line with our Constitutional mandate of the progressive realisation of health care. If there's a problem with protocol we need to tackle it to see if it's reasonable and what the implications are for other patients.'

She said protecting patient rights needed to concur with 'following processes'.

Chairperson of the Human Rights Commission, Jody Kollapen, disagreed. He said that while he recognised protocols, 'they undermine the duty to speak out – this needs to be revisited. At the heart of the problem are not just interests of the department but those of the broader public.'

Asked by Professor Martin Veller, head of surgery at Wits, whether viewing the controversy from a 'demand instead of a supply perspective' might be helpful, Williams said several countries had a huge backlog of unmet demands with little or no resources. 'It's not that easy to reduce demand overall, especially when so many people are ill.' He conceded that the ideal approach would be to put a greater emphasis on prevention, citing road accidents, tobacco control and lifestyle changes – but this fell outside of the health care system. 'The question is how many resources do you put into those programmes which will eventually but not immediately reduce demand on the health care system? But this takes money from acute care to preventive care,' he added.