Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versão impressa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.98 no.10 Pretoria Out. 2008

HIV prevention needs to confront the elephant on the road

D B Harrison

MB ChB, MSc (Med), MPP. loveLife, Johannesburg

To the Editor: On a recent trip to a loveLife youth centre in Nongoma in KwaZulu-Natal, we encountered an angry elephant on the road. It wouldn't budge. So far and no further - until a taxi driver eventually confronted the beast with blaring horn. Driving on, we came across a watering hole - this time for humans - called the Why Not Tavern. Why not, indeed? Why not get drunk? Why not have unprotected sex? In the absence of something to do, tomorrow may be no different from today. In fact, it's as if tomorrow never comes.

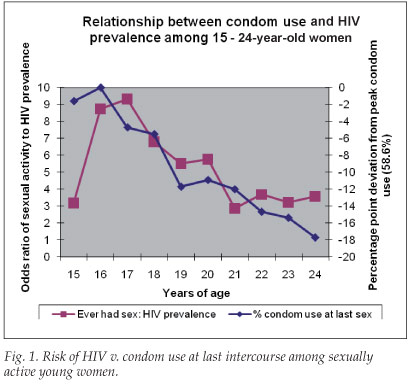

We ask: Why do young people who know the risk still have unprotected sex? It's an imprecise question; while some who have sex never use condoms, many others start off using them and then stop. A national household survey of close to 12 000 15 - 24-year-olds conducted in 2003 found that condom use among sexually active women peaked at age 16 and then declined sharply. Not surprisingly, the correlation between sexual activity and HIV increased steadily until 21 years of age, when levels of infection were saturated (Fig. 1).1

The life event that precipitates this marked change in sexual behaviour is school-leaving, either through dropping out or completion.2 In fact, half the total lifetime risk of HIV is crammed into just 5 years after leaving school.

Why would young women, who had initially protected themselves, subsequently take risks? The intuitive explanation - a desire to have a baby - is not supported by the fact that two-thirds of 15 - 19 and 20 - 24-year-old women who had been pregnant said that their pregnancy was unwanted. Other significant predictors of condom use, including condom self-efficacy, duration of relationship and beliefs about marriage,3 do not show enough age-specific variation to explain the decline.

The probable answer is that a significant proportion of young people succumb to a set of social constraints and expectations that prevail when they leave school. This state of limbo - described by popular rap artist Sista Bettina as living 'in the meantime' - shapes both social and sexual behaviour. To a young woman in an informal settlement, unemployed and insecure, acquiescence to immediate economic pressures and social expectations may seem rational and to be for her own good. Compliance often takes the form of partnership with a man who provides physical and material 'protection' in exchange for unprotected sex.

At some point in the lives of many young people, chronic disappointment and persistent rejection wear down their sense of 'possibility' - of life's potentials. Risky behaviour is not such a big deal, even though they've got the message. That's why young people still have unprotected sex.

A more challenging question is why people in such circumstances should not have unprotected sex. The easy answer - that there's a lot to live for - has long underpinned most approaches to risk reduction. Yet studies consistently show high levels (>90%) of optimism among South African youth - generally defined as a sense of utility in the long term, quite distinct from the pressing concerns of everyday life. Therefore an appeal to their vague sense of future beneficence is hardly compelling. They will only move out of 'the meantime' if their lives gain incremental momentum, starting now.

Interestingly, people living in rural traditional homesteads are relatively protected from HIV, compared with those in urban informal settlements.4 Poverty seems to predispose to infection in the presence of other factors such as social exclusion or family disruption. In cross-country comparisons, income polarisation emerges as a stronger determinant of HIV infection than absolute poverty.5

Most advocates of behaviour change recognise the socio-economic drivers of HIV infection,6 and have combined local development and communication strategies in their prevention efforts. However, taking on the national burden of poverty and inequality is overwhelming, and could diffuse the focus and place even existing gains at risk.

In South Africa, inroads have been made in reducing HIV infection among teenagers, and stepping up exposure to good sexuality education will take us even further. But the spike of infection in school-leavers suggests that we will not reach the turnaround point without confronting the elephant in the road.

Possibly the most dominant effect of all - the impact of socio-economic polarisation - remains unchallenged.

One point of intervention may be the nexus between social and individual determinants of HIV infection. At some point in the chain, structural factors trigger behavioural effects. A better understanding of the psychological triggers could open new avenues for intervention. Our view is that perception of day-to-day opportunity is a pivotal mediator of structural influence on individual behaviour. Through this cognitive link, the constrained choices and sense of exclusion inherent in polarised societies predispose to higher levels of personal risk. The clincher would be strong independent associations between an individual's sense of immediate possibility, resilience and inclusion, and lower rates of HIV. Unfortunately, there are still yawning gaps in our knowledge, and this is an important area for further research.

We believe, however, that there are enough insights to suggest that changing perceptions of opportunity should be central to behavioural interventions. Some would argue that life-skills programmes do just that. To the extent that they build 'look-for-opportunity', 'get-up-and-go' and 'get-up-again' mindsets, that is true. But we also need to create pathways for young people that link them to opportunity. In this regard, new technologies such as mobile social networks could help by creating immediate and interactive access to information. (Three-quarters of 15 - 24-year-olds in informal settlements have cellphones.)

Perhaps more fundamentally, we should capitalise on the leadership of young people themselves. Too often, they are regarded merely as purveyors of the message. Yet it is these young people, drawn from marginalised communities and self-selected through service, who could create precedents and pathways for others and build solidarity at the same time. A national network of 5 000 entrepreneurial young leaders - linked to opportunities for personal growth - could create a sense of innovation in stagnating communities. It won't drive away the elephant anytime soon, but could get it moving.

References

1. Pettifor A, Rees H, Kleinschmidt I, et al. Young people's sexual health in South Africa: HIV prevalence and sexual behaviours from a nationally representative household survey. AIDS 2005; 19: 1525-1534. [ Links ]

2. Hargreaves J, Morison L, Kim J, et al. The association between school attendance, HIV infection and sexual behaviour in rural South Africa. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008; 62: 113-119. [ Links ]

3. Sayles J, Pettifor A, Wong M, et al. Factors Associated with self-efficacy for condom use and sexual negotiation among South African youth. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006; 43(2): 226-233. [ Links ]

4. Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi L, et al. South African National HIV Prevalence, HIV Incidence, Behaviour and Communication Survey. Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2005. [ Links ]

5. Zanakis S, Alvarez C, Li V. Socio-economic determinants of HIV/AIDS pandemic and nations efficiencies. Eur J Operat Res 2007; 176(3): 1811-1838. [ Links ]

6. Wellings K, Collumbien M, Slaymaker E, Singh S, Patel D, Bajos N. Sexual behaviour in context: a global perspective. Lancet 2006; 368: 1706-1728. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

D Harrison

(david@lovvelife.org.za)

Accepted 13 May 2008.