Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versión impresa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.98 no.10 Pretoria oct. 2008

IZINDABA

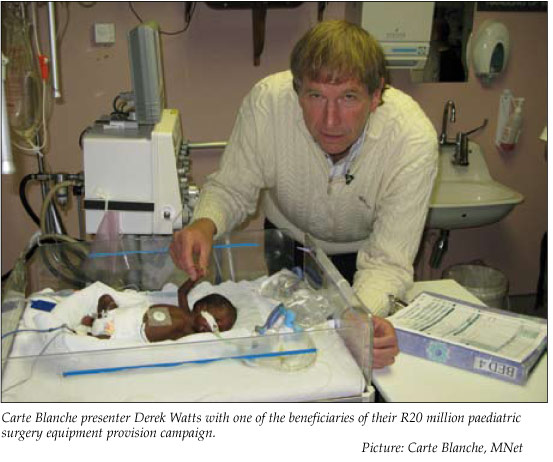

Media 'knight' breathes life into paediatric ICUs

Chris Bateman

Senior surgeons say the lack of paediatric ICU beds at Johannesburg Hospital and Chris Hani-Baragwanath Hospital costs the lives of at least 60 babies a year - leading a media knight in shining armour to launch a rescue crusade to provide essential equipment to them and 3 other hospitals.

Carte Blanche, the hard-hitting M-Net television investigative programme, also targeted the paediatric surgical departments at King Edward Hospital (KwaZulu-Natal), Bloemfontein Academic and Pretoria Academic hospitals for a 7-week, R20 million fund-raising blitz to mark their own 20th anniversary.

At Chris Hani-Baragwanath Hospital, not a single item of equipment ordered through official channels by the paediatric surgical department over the past 2.5 years has been delivered. Doctors have privately despaired of their support administration and reverted to the private sector for life-saving equipment.

Each Sunday evening the results of the carefully targeted funds and the clinicians who guided the life-enhancing and life-saving purchases, as well as the work of Johannesburg Child Welfare and its sister Parent and Child Counselling Centre, were profiled for viewers nationwide.

Izindaba established that at Chris Hani-Baragwanath Hospital not a single item of equipment ordered through official channels by the paediatric surgical department over the past 2½ years has been delivered. Doctors have privately despaired of their support administration and reverted to the private sector for life-saving equipment.

One item, a cystoscope, used to help cut open malfunctioning valves in infants' bladders, was recently obtained via the Wits Medical School private trust (SurgiKids), resulting in surgeons being able to conduct a single operation leading to an unscarred patient being discharged within a day.

Previously, babies with this condition needed three operations over 20 days, with increased anaesthetic risk and significant scarring. This is but one example of how administrative incompetence and underfunding are contributing to mortality and morbidity.

The Carte Blanche intervention, while a 'legitimate and sincere attempt to help', was described by one senior surgeon as 'a short-term band-aid solution for a much more fundamental problem'.

From April to July this year, a review of Bara's paediatric surgical department showed that the 'luckier' malnourished babies referred there from outside hospitals had an average waiting time of 11.5 days from diagnosis to securing an operation (mainly for an obstructed gastrointestinal tract). Many others who presented with acute problems like gastroschisis simply died because of insufficient ICU beds. Lack of diagnostic expertise in more rural hospitals and clinics contributed to the death toll.

Dr Bob Banieghbal, a senior paediatric surgeon for the past 3 years at Johannesburg General Hospital and a veteran of 10 years at Bara, said he lost about 'a child a month' headed for his ICU, while at Bara 'they lose 3 - 4 kids per month'.

When it was put to Bara's paediatric surgery chief, Professor Graeme Pitcher, that up to 48 babies a year were dying in his unit, he responded, 'that's conservative, it's probably closer to 60'.

The mortality pattern was echoed at Pretoria Academic Hospital, where the head of paediatric surgery, Dr Ernst Mueller, said a constant headache was the 'very slow provision of much needed equipment'.

Sadly, senior officials at some of the hospitals most in the news over avoidable baby deaths, Frere Hospital in East London and Dora Nginza in Port Elizabeth, subject to Carte Blanche’s exposés in the past, baulked when approached with the free equipment offer and lost out.

While unable to provide exact figures he said, 'we have a similar mortality situation to the others. Basically ICU beds with all the bells and whistles is what enables us to save lives, plus obviously staff.'

The surgeons said ventilators, IV machines, new-generation endoscopic (video) equipment and 'the physical ability to send patients to ICU beds', were top of their needs lists.

Banieghbal said that at Johannesburg General, for every 10 ICU bed requests, 8 were granted, while 1 of the 2 remaining luckless patients normally died.

'The staff problem can be a bit of a catch 22, but if you first create another 4 - 6 ICU beds and then advertise aggressively for staff, it's do-able,' he added.

A feature of the Carte Blanche coverage was how careful the doctors were not to tread on any official toes, or as one put it, 'we wanted viewers to respond to the need, not to antagonise the hospital'.

Bisho says 'no thanks'

Sadly, senior officials at some of the hospitals most in the news over avoidable baby deaths, Frere Hospital in East London and Dora Nginza in Port Elizabeth, subject to Carte Blanche's exposes in the past, baulked when approached with the free equipment offer and lost out.

CEO of the East London Hospital Complex (ELHC) (Frere and Cecilia Makiwane Hospitals), Mr Vuyo Mosana, told Izindaba that George Mazarakis, the executive producer of Carte Blanche, called him on 5 August.

A 'misunderstanding' during a sharp exchange between him and Mazarakis and 'head office reluctance in Bisho' (earlier) led to a communication breakdown.

'I asked him to send me an e-mail with details of sponsors and promised I would talk to whoever needs to give the nod at head office. No man! We're not reluctant. He (Mazarakis) was a bit rude and spoke of paranoia - I don't know what this paranoia is about, because if it was so, I wouldn't be talking to him!'

Mosana speculated that Mazarakis' patience ran thin because of the initial 'not that positive' response from Bisho, in an approach facilitated by Dr Jerry Boone, the ELHC's head of paediatrics, through his acting clinical senior.

He asked Izindaba to 'please give me his (Mazarakis') number so I can call him,' adding, 'I'm still awaiting his e-mail. Once I get a look at my needs list, we can talk as a matter of urgency.'

Boone could not be reached for comment but Dr Alan Atherstone, ELHC's chief of surgery, said it would not be the first time equipment had been donated to their hospitals.

'Yes, there are procedures. It's a matter of filling in a form and getting it authorised. I'd be very happy to get some donated equipment. Actually paediatric surgery at Frere runs very well and has some very up-to-date stuff - they even have a good complement of senior staff but are short of juniors. However, not all departments are running that well and we could do with equipment. This is a bit ridiculous,' he added, promising to raise the matter with Mosana.

Upon being told of the Frere Hospital donation debacle, Banieghbal responded, 'The government is very conscious of these (mortality) figures. It's hard to hear "you've let us down".

They've spent money on inappropriate equipment (submarines and jet fighters) - it doesn't take a very intelligent person to see the wastage of our resources.'

Warm hands needed for cold equipment

Professor Peter Cooper, head of paediatrics at Johannesburg Hospital and academic head at Wits University, expressed doubt over whether suddenly expanding his paediatric ICU by 4 beds would result in the necessary recruitment of appropriately qualified nurses, although recently hiked salaries 'might help'.

He echoed Banieghbal's assessment, saying 'I guess we're providing up to 80% of (ICU) beds for those who need them'.

'It's a bit of a chicken and egg situation. When you improve facilities you make it more attractive for staff to work there as well - but the hospitals are grossly under-funded.'

Cooper said that while Johannesburg General worked closely with other units around Gauteng, 'as you go further out into surrounding provinces there's very little in the way of ICU facilities'.

Mazarakis told Izindaba that Carte Blanche was viewed with 'some degree of suspicion in the bureaucratic hierarchy of some of the hospitals

- with a degree of justification, given who we are.

We usually enter those hospitals looking for something that's wrong. And here we are saying, we know there are things that are wrong, we can help to make them right. Some have been so suspicious that they've said, thank you very much but no thank you, we don't need your assistance.'

He said this was 'a grave pity, because they're really the hospitals that need it the most,' adding that Frere and Dora Nginza hospitals were targeted 'because we felt they were the most needy'.

He said there were 'degrees of alacrity' in the responses of hospitals approached.

'Everybody was suspicious and some presented very thin wish lists; we were surprised. But once they cottoned on, the wish lists grew.'

The lists varied in content from ICU beds, cribs and monitors, infusion pumps, cranial ultrasound machines, cardiac perfusion systems, dialysis machines, resuscitation trolleys, neonatal ventilators, fibre endoscopes and operating headlights, 'to name a few'.

Asked why Carte Blanche had singled out paediatric surgery instead of, say, prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission or antiretroviral and/ or antenatal clinics, Mazarakis said choosing 'something like that becomes too complicated - it's not visual. You have to be practical. We'd done stories on all those issues and have dealt with HIV-positive patients in this series. The practical reality is we have 2 days in which to shoot each insert.'

The genesis of the idea came at a dinner party in July where he met a woman friend who had lost a baby in Australia and who spoke enthusiastically about a fund-raising community-based programme there.

She put him in touch with UCT graduate and assistant director of clinical operations at Sydney Children's Hospital, Dr Johnny Taitz, who said the foundation attached to his hospital had played an 'immense' role in providing all the extras that made it 'so fantastic'.

He said that while State hospitals were 'bureaucratic organisations', they were' populated by extraordinary people'.

'I think similar foundations (each of the 5 Carte Blanche-chosen hospitals have one) in South Africa could learn from the way we operate in Sydney, the way the foundation galvanises community support to drive urgently needed equipment and resources for the hospital.'

Mazarakis said Carte Blanche viewers had proved enormously generous in responding to the plights of various people highlighted in the past, 'so why not borrow a successful model from another country'?

The two child welfare organisations they profiled were 'dealing with an onslaught of abandoned and orphaned children - we'll see the conditions they work under, what they most need and ask our viewers and corporates to help'.

He said that while State hospitals were 'bureaucratic organisations', they were 'populated by extraordinary people'.

'We've met some of the most remarkable human beings - angels of mercy really. These are people dedicated to saving lives and putting themselves in second place in order to achieve that.'

The Sydney Children's Hospital Foundation had affected the lives of hundreds of thousands of children throughout Australia.

'If we in South Africa over 7 weeks can do a fraction of that, it would be Carte Blanche's ultimate birthday present.'