Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.98 n.8 Pretoria Aug. 2008

IZINDABA

Lack of humanity our biggest disability

Chris Bateman

Being unable to use his limbs is far less of a disability than the challenge posed by the societal attitudes he encounters - and that includes doctors who seem to believe they 'know what's best for the C4 in bed 6'.

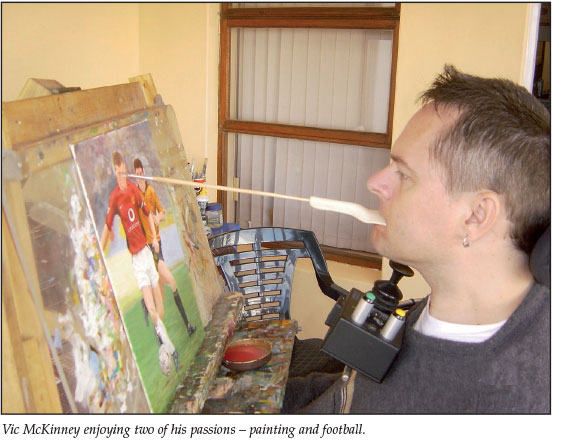

Vic McKinney (39), rendered quadriplegic by an extraordinary road accident involving a falling tree that killed his Irish national footballer father, Vic senior, when it smashed onto their car in Edinburgh Drive, Cape Town, just over 20 years ago, secured his MPhil in Disability Studies from UCT in June this year.

Izindaba, curious about how a 19-year-old Michaelis Fine Arts student and UCT first team soccer player clawed his way back from tragedy to personal and academic success, sought him out at his Marina da Gama home last month.

McKinney's views are as resolute as the willpower and attitude he's developed, not least by working in disadvantaged communities where he's been an inspiration to people attending rehabilitation centres in Khayelitsha and Mitchell's Plain.

Those views include one highly critical of 'the medical model'- and some doctors - whom he acknowledges for their contribution to his recovery, but says often fail to hear the voices of disabled people, especially when they question a doctor's opinion.

'I find some of the arguments I've had with doctors amazing. One guy told me in the middle of a corridor that because I was a C4 quad I must have a catheter. When I told him that I didn't, which is to my obvious benefit, he couldn't see past the textbook. It's scary; here's a man of intelligence ...that opened my eyes to how fallible doctors are and how rigid and unresponsive the system can be.'

McKinney has sympathy for the difficulties doctors face and a lot of his good friends are in the profession. He says he's realised that there are two kinds of patients: those who want the doctor to take responsibility for their ailment and those who 'come in, want to get better and will take responsibility for it'.

Doctors 'know best'

However, 'when you're put in a position where you have no choice and you question the doctor's methods, you don't have a voice - that was our experience, my Mum's and mine'.

The patient with a disability or his family 'could not possibly know' what was best.

'I know exactly how my body works and learnt the medical terms so I could relate to doctors using the language they speak,' says the near 1.8 metre tall McKinney, who has custom-designed his own self-propelled wheelchair, along with a friend who makes them.

He described how at a scoliosis clinic where doctors saw him regularly, 'they wanted to take me out of my chair and put me on a hard wooden bench and bend me forward so they could see my spine'.

'Firstly, sitting on a hard bench can develop pressure sores and secondly, bending over like that would have defeated the purpose because I would be in a totally unnatural position.' After 8 years of attending scoliosis clinics he knew this ... and explained the positioning of his spine to the specialist.

Adding to his incredulity, a top Conradie Hospital neurosurgeon challenged the attending physician and asked him if he was 'going to take the patient's word for it'.

McKinney says a recurring problem in the medical fraternity was the disbelief that a person with a disability could know what their body was about.

While he understood the difficulties faced by a doctor who saw 20 patients a day, he asked 'surely you want to empower people? - which is why ideally you have a team of people so a holistic approach can be taken'.

When a relatively intelligent person like himself questioned what the doctor was doing, sometimes it's like their little empire gets threatened, there's a kind of a power dynamic and they can get really nasty and make life more difficult than needs be for a quad in hospital, including their families. It's a very human thing, but a hard fact.

'I don't think they always appreciate the trauma a person is trying to deal with, especially when they talk about the C4 in bed 6.'

McKinney admits to having bought into the medical model when he first experienced being unable to get up at 02h00 and paint when the muse was upon him. 'It was so great to have that freedom. When the same kind of ideas hit me after the accident I would implode instead of creatively explode,' he said.

'I pathologised myself'

His 'biggest hang-up' for a long time was that anything he did was 'never going to be as good as it could have been. I felt very nipped in the bud.'

There was no escaping the medical model in hospital 'and you buy into what you're told; you pathologise yourself. You've no idea what paralysis is about and you're experiencing in yourself an inability to do what you want, so you start buying into the "I am disabled" school of thinking - that's what I did.'

Reinforcement came in the form of people staring and it taking 90 minutes to simply get up in the morning. 'It's pretty easy to say, ag well stuff it! But my mother is an amazing woman with remarkable strength and gave me what I needed on a very practical level.'

What helped, although he has mixed feelings about 'deserving it', was a settlement reached with the City of Cape Town after 3 years of protracted court proceedings.

This gave him the financial means for a home and support staff to bolster recovery and develop self-sufficiency. There was little time to grieve his father 'and best friend' Vic senior initially, and the additional trauma of his first 3 years of adaptation took another decade to get over.

Passionate involvement in township disability day care centres, where violence and sexual abuse were endemic, 'was in many ways my salvation'. 'I discovered I could make a difference. I don't think of myself as disabled. My chair and my body are things I carry around with me. Mentally I'm moving all the time, dancing, kicking a ball'.

McKinney sees disability as '90% psychological - it's all about attitude, like life'. He describes his condition as 'like walking through mud'. 'Other people on shore walk quickly. For me it's like walking through water or mud, it just takes you longer to get there. Disability can be so tedious, almost mind-numbing and you have got to fight that.'

Integration of disabled urgently needed

He believes the lack of visibility of disabled people in society (in spite of 14% of South Africans being disabled in some way) and the failure to integrate them into the mainstream are mainly to blame for such widespread prejudice and ignorance.

'We've done gender and racism, but disability has been shelved,' he added. He describes how more than once, while drinking a can of Coke and waiting for his girlfriend to finish shopping at a supermarket, passers-by would stop and drop coins into the can. It's a common experience for people with disabilities.

'People simply don't know how to relate outside of the charity model - and it all stems from the medical model for disability.' He believes a big part of the solution lies in inclusive education from an early age, and cites his girlfriend moving from a Waldorf school where she had experienced racially diverse classrooms 'from day one', to a Model C school. 'She just couldn't understand what all the fuss involving race was about.'

One of the biggest catalysts for his own change in attitude, after years of 'just surviving and even planning a 5-year exit strategy' (suicide), was being in Nelson Mandela's presidential office in 1995 to deliver some greeting cards he had designed. Madiba's secretary said 'come and meet him'. 'I remember sitting alone in his office looking at the new flag and its simple design and thinking there's been a real change here. It hit me that for years and years I'd been in the mindset that one man can't make a difference. I vowed to get with the programme and influence things.'

A 'Madiba moment'

The president of Mauritius flew in and 'stole his (audience) moment', but the Madiba magic had already worked, and with further catalysts being his caregivers from Khayelitsha and Mitchell's Plain, McKinney soon discovered fulfilment in service of others.

He cannot stand any kind of patronising charity and despises tokenism, remembering how he won the Michaelis Art School prize for the 'most promising student' after his accident. 'It was a book voucher and to this day I've never used it because I felt I got it because of my position. Their intention was good but I battle sometimes to know if people are praising me out of merit or because of my situation. I think I've matured a bit and now take compliments from where they come.'

He's also been 'prayed for so many times that it's a miracle I cannot walk!' People think he's extraordinary but his reaction is that he's just doing what other people are.

'Bergies love me. I've always chatted to them, even since I was a kid and now I've had 10 of them carry me up a flight of stairs, reeking of alcohol. It's a psychological thing I think, I find it really interesting. They seem to have failed in life and there's this feeling they have of here's this guy, ag shame, but he's doing it. It makes them aware of the fallibility within themselves and they realise they can be of help to me and it makes them feel good to be able to do that. I think it's part of our human need to be needed.'

Asked to choose what would most help disabled people in South Africa in the long term, McKinney says transport and accessible buildings would help make disability 'visible' and enable those disabled to do what most take for granted, particularly in the labour market. Yet the single most important factor was attitude and people 'getting in touch with their humanity'.

'Generally, I don't think society takes disability seriously at all and certainly does not understand the magnitude of it. Disabled people are viewed as sexless and unable to work, so on a fundamental level are not viewed as being important enough to include - and the status quo reinforces this.'

Sometimes little things still get to him, but on the whole he's stopped being angry and is now dedicated to trying to educate and break the patterns of ignorance. 'Heaven knows, you can lose perspective fighting for a cause, especially when it is so personal and relates to all aspects of your daily life. The best I can do is live a regular life, do what inspires me and that way inspire others, be they disabled or not. Forget this, there but for the grace of God go I. It's rubbish, not walking is the least of my problems. Societal attitudes get in my way more than anything. Just listen to and help each other and get on with it, that way life's far more rewarding.'