Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.98 n.6 Pretoria Jun. 2008

ORIGINAL ARTICLES

Homicide trends in the Mthatha area between 1993 and 2005

B L Meel

MB BS, MD, DHSM, MPhil. Faculty of Health Sciences, Walter Sisulu University for Technology and Science, Mthatha, E Cape

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Absolute poverty and gross income inequity can foment violence through various and multiple mechanisms. Poor people are highly prone to exploitation and manipulation by those who are wealthy and more powerful. The poor are as susceptible to being victims as being perpetrators of crime.

OBJECTIVE: To study the trends in homicides in the Mthatha area.

METHOD: A review of records of 5 583 medico-legal autopsies in Mthatha General Hospital of murder victims between 1993 and 2005.

RESULTS: During the 13-year period, 12 063 autopsies were performed on people who died following trauma and other fatal injuries. Of this total, 5 583 (46%) were homicides. The average annual homicide rate during this period was 108/100 000 population. The rate increased from 94/100 000 in 1993 to 133/100 000 in 2005. Firearm-related deaths averaged 48/100 000, stab wounds 35/100 000, and blunt trauma (assault) 25/100 000 per year.

Gunshot-related homicides increased from 27/100 000 in 1993 to a peak of 68/100 000 in 2001, decreasing to 42/100 000 in 2005. Stab-related homicides ranged from 42/100 000 in 1993 to a 'low' of 26/100 000 in 1995, then rose to 53/100 000 in 2005; assault with blunt objects increased from 25/100 000 to 38/100 000 in the same period. Murdered males (82%) outnumbered females in the proportion of 5:1, although there was an increasing incidence of females. About half of these deaths were in the 21 - 40-year-old range.

CONCLUSION: There has been a progressive increase in homicides in the Mthatha area. To a certain extent, poverty has contributed to the causation of these deaths.

Globally, around 520 000 people a year die as a result of interpersonal violence. That equates to 1 400 deaths every single day, week in and week out, year after year. Most victims and perpetrators of interpersonal violence are between 15 and 44 years old.1

Interpersonal violence and injuries account for 5 million deaths a year - 9% of global mortality. Eight of the 15 leading causes of death for people between the ages of 15 and 29 years are injury-related. Over 1.6 million people a year worldwide lose their lives to violence, of whom 90% are in developing countries. Violence is among the leading causes of death for people aged 15 - 44 years worldwide, accounting for 14% of deaths among males and 7% of deaths among females.2 If current trends continue, the global injury burden will have risen dramatically by the year 2020. Injury and death rates are significantly higher in low- and middle-income countries.3 In addition to the 520 000 people who die each year due to interpersonal violence, millions more sustain non-fatal injuries from violence.4

The National Injury Mortality Surveillance System (NIMSS) showed in 2002 that the most common apparent manner of non-natural death in South Africa was homicide, which accounted for 45.4% of all fatal injuries. The leading cause of death among males was homicide; firearms contributed to 29% and sharp-force injuries to 14.5%. The average age of victims was 31 years. Blood alcohol levels were present in 11 927 (47%) out of the total of 25 494.5 A South African is 12 times more likely to be murdered than an average Westerner. Between April 2004 and March 2005, approximately 18 000 were murdered (an average of 51 per day) in a nation of 47 million. Approximately 24 000 attempted murders, 55 000 reported rapes and 249 000 grievous bodily harm cases occurred during the same period. This is an extraordinarily violent society, the reasons for which are not well understood.6

South Africa exemplifies the dichotomous economy of considerable wealth in the hands of a few, and a large part of the population without wealth. The poverty level is about 45% and does not seem to be falling: nearly 20 million citizens live at or below the poverty line. Poverty is largely coupled with high and rising unemployment (currently 40%), and widening income inequality (Gini coefficient 0.58).7 The number of shacks increases at nearly 8% a year - from 1.45 million in 1996 to 2.14 million in 2003. According to official figures, 1 out of every 5 South Africans will have died from AIDS by 2015, i.e. around 10 million people.8 The purpose of this paper, however, is to highlight the problem of homicide in the Mthatha area.

Method

The records of 5 583 medico-legal autopsies on murder victims between 1993 and 2005, conducted in Mthatha General Hospital, were studied. The mortuary is on the hospital premises (the teaching hospital of the University of Transkei, now Walter Sisulu University) in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Recorded details included names, addresses and ages of the deceased, and the causes of death. The referrals were mainly from the Mthatha and Nqgeleni magisterial districts (combined population of 400 000). All autopsy records for the specified period were reviewed, compiled and collated manually. All statistical data were represented per 100 000 population. Age groups and gender statistics were not available in 2005, and are therefore omitted in this paper. In some cases, age and gender were not recorded in the register, and therefore omitted from the tables. Assault means intentional injury inflicted by a blunt object. An analysis of the records was also carried out manually and then, with the help of a computer, the results were presented in tabular and graphic form.

Results

During the 13-year-period, 12 063 autopsies were performed on those who died from physical trauma and other unnatural causes of death. Of these, 5 583 (46%) were homicide victims.5 The average number of deaths from homicide during this period was 108/100 000 population per year. The rate increased from 94/100 000 in 1993 to 133/100 000 in 2005 (Table I). Firearm-related deaths averaged 48/100 000, stabbings 35/100 000, and blunt trauma (assault) 25/100 000 per year.

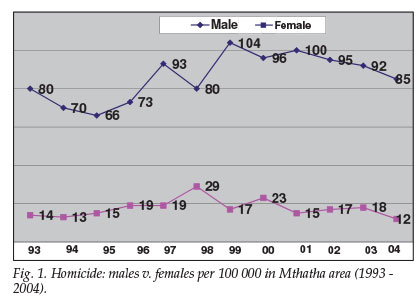

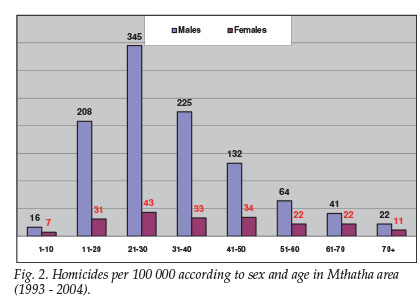

Gunshot-related homicides increased from 27/100 000 in 1993 to 42/100 000 in 2005. Stab-related homicides also increased, from 42/100 000 in 1993 to 53/100 000 in 2005, and assault by blunt objects from 25/100 000 to 38/100 000 in the same period. Male deaths outnumbered females by 5:1 (Fig. 1). Gunshot deaths for females rose from 3.8/100 000 in 1993 to 6/100 000 in 2004, and for males from 23 to 32/100 000 in the same period. The highest number of homicide deaths (388/100 000) occurred in the 21 - 30-year-old group (Fig. 2).

Discussion

There is an enormous amount of literature in the lay press on homicide, but very few published studies; this paper is believed to be the first for this area. Mthatha was the capital city of the former black 'homeland' of Transkei, which is now part of Eastern Cape Province - one of South Africa's poorest provinces. Eastern Cape has a population of 7 million, of whom nearly 4 million inhabit the Transkei region. Close to three-quarters (74%) of the province's population e arn less than R1 500 per month, and 41% of households have a monthly income under R500 per month. The Eastern Cape has the country's second-highest proportion of poor (44.5%) - with the equivalent figure in the Transkei no less than 92%.9 Unemployment increased from 36% in 1996 to 43% in 2001, and poverty from 34% to 39% during the same period, in Eastern Cape.10

Of the total of 12 063 unnatural deaths reported between 1993 and 2005, 5 583 (46%) were the result of shooting, stabbing or assault with a blunt object. Crime of this nature and magnitude has widespread effects in the area. The murder of one person, especially a breadwinner, leads to emotional and physical suffering for the survivors, who sometimes become totally destitute. With survival at risk, a high proportion of people carry guns or knives. A NIMSS study on homicide was limited to metropolitan areas such as Cape Town, Johannesburg, Durban, Port Elizabeth, and Pretoria. It is generally presumed that most homicides occur in urban areas, but this is not necessarily so. Rural populations have less access to, and fewer, resources than urban. They are much poorer and weaker, and also at higher risk of injury because they are confronted more frequently with hazardous situations. Their chances of survival or making good recoveries when seriously injured are reduced because they have fewer and more distant health services. It is an unfortunate forecast that injuries and deaths from violent causes are likely to continue increasing.11

The murder rate has reached epidemic proportions. For several years in succession, an average of 25 000 people per year have been murdered in South Africa. Countries with a very large gap between rich and poor tend to manifest more violence than countries in which the gap is substantially smaller, regardless of the absolute income levels of the nation.4 Absolute poverty and gross income inequality is widespread in the area under review. Poverty and unemployment are probably the major factors behind the causes of high violence in the area.10

In 1998, the murder rate in the USA was 6/100 000, while in South Africa it was 59/100 000.12 In Colombia, the homicide rate of 62/100 000 is the highest in the world, but that for the Mthatha area is 75% higher than Colombia.13 Reasons for the high number of homicides in this rural and semi-rural part of South Africa have not been propounded; neither have attempts been made to investigate them. Mthatha and surrounding areas in the Transkei region are different from other parts of South Africa, not only in terms of wealth but also the results of rigorous application of apartheid policies which led to fragmentation of families and weakening of cohesion within clans and communities. Poverty has compounded all these issues.

South Africa is the most developed country in Africa. Yet it has particularly many murders - about 250% higher than the average homicide rate for sub-Saharan Africa, and more than 10 times the global average.14 The average homicide rate in South Africa is 59/100 000 per year, which is just over half that for the Mthatha area, of 108/100 000.15 The Mthatha homicide rate in 1993 was 94/100 000 of population, increasing to 133/100 000 in 2005 (Table I and Fig. 1). This 150% increase over 13 years has partly been blamed on high unemployment and growing poverty. While all social classes experience violence, research consistently suggests that it manifests most among people in the lowest socio-economic groups. The mechanisms are complex and not well understood or analysed, but evidence is that both absolute poverty and income inequality are related to levels of violence. Studies have shown that homicide is more prevalent in low-income communities and countries than in high-income communities and countries.4

Homicide by shooting is the most common (48/100 000) form of killing in the Mthatha area. It increased from 42/100 000 in 1993 to a peak of 68/100 000 in 2001, coming down to 42/100 000 in 2005. This downward trend could have been a result of stricter gun control and firearm licence requirements. Nevertheless, South Africa has one of the highest firearm-related homicide rates in the world - second only to Colombia.15 In 2005, the incidence of shooting deaths declined in the area, but deaths by stabbing and striking with blunt objects increased. The overall result was an increase in homicides.

Young males are predominantly the perpetrators and the victims of violent deaths. They have an inherent risk-taking tendency, which is often boosted by alcohol and drugs. The overall ratio of male to female murder victims is close to 5:1 (Fig.1). The preponderance of young male adult homicides appears to be a universal phenomenon.16 In the Mthatha area, the age group of 21 - 30 years showed the highest rate of homicides in the period under review, of 388/100 000 (Fig. 2).

In the year 2000, approximately 200 000 youths were murdered globally. An average of 565 children and young adults from 10 to 29 years of age die each day as a result of interpersonal violence.17 This group includes youths and adults who are generally at peak sexual activity, consume alcohol, and carry lethal weapons.18 The majority of victims and perpetrators of homicide are African males.

Historically and culturally, in the indigenous black population, it has been the role of women to look after the family and raise children, while males are regarded as warriors. This mindset still exists in the greater community and, as a result, many men carry knives or firearms. In the majority of cases of murdered women, the perpetrators were their male partners. A large number of males consume alcohol or drugs and commit crimes while under their influence. In all countries, young males comprise the majority of victims as well as perpetrators of homicide. The highest rate is among the age range of 15 - 29 years, namely 156/100 000 in sub-Saharan Africa, 68/100 000 in Latin-American and Caribbean countries, and 34/100 000 in the United States.15 In the Mthatha area, the peak annual figure of 388/100 000 was far higher than other countries as well as other areas of South Africa (Fig. 2).

To combat the high level of homicide in this area, poverty has to be tackled first. One of the major reasons for the link between poverty and violent crime is the need for food - an essential for survival. The socio-economic impact of murder is very high and has adverse consequences for development of the area. The HIV/AIDS pandemic compounds the issue. Empowering the weak and the needy, and providing more resources to law enforcement agencies, should be a priority. More young lives will continue to be lost until these things are done.

In short: the rate of homicide in the Mthatha area is exceptionally high and increasing, and especially affects the younger age groups and economically weak segments of the community. The key to solving this murderous trend is alleviation of poverty.

I thank part-time doctors Dr M B Mafanya, Dr S Qaba, Professor M Garcia and other mortuary staff for their contribution in autopsies. My special thanks to Dr G Rupesinghe, a Principal Specialist in the Department of Family Medicine, Umtata General Hospital, and Professor E Kwizera, Department of Pharmacology, for help in editing this article.

References

1. Preventing Violence: A guide to implementing the recommendations of the world report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004. [ Links ]

2. Injuries, Violence and Disabilities. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2006. [ Links ]

3. Developing policies to prevent injuries and violence: Guidelines for policy-makers and planners. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2006. [ Links ]

4. Violence Prevention Alliance. Building global commitment for violence prevention. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2005. [ Links ]

5. Matzopoulos R, Seedat M, Cassim M. A profile of fatal injuries in South Africa. In: Fourth Annual Report of the National Injury Mortality Surveillance System (NIMSS). Cape Town: South African Medical Research Council, 2002. [ Links ]

6. Leonard T. South African murders hit scary rate. Washington Post, 26 August 2006. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/08/26/AR2006082600286_pf.html (accessed 26 October 2007). [ Links ]

7. Geographical partnership. EU relations with South Africa. European Commission. http://ec.europa.eu/development/Geographical/RegionsCountries/Countries/South%20Africa.htm (accessed 27 October 2007). [ Links ]

8. The New South Africa. Statement of Lindiwe Sisulu, Minister of Housing. http://thenewsouthafrica.blogspirit.com/the_new_government/ (accessed 9 September 2006). [ Links ]

9. Rural Development Framework Document (ECSECC). Bhisho: Office of Eastern Cape Premier, October 2000. http://www.ecsecc.org/pgdp.asp (accessed 27 October 2007). [ Links ]

10. Programme of the Second Annual Rural Development Conference, 27 - 29 September 2006. Mthatha: WSU Centre for Rural Development, 2006. [ Links ]

11. Non-communicable Disease, Mental Health and Injuries. Geneva: World Health Organization 2002, 1-21. [ Links ]

12. South Africa's murder rate far worse than reported, 2006. http://www.originaldissent.com/forums/archives/index (accessed 30 September 2006). [ Links ]

13. Murder (per capita) by country. Seventh survey of crime trends and operations of criminal justice systems (1998-2000). New York: Centre for International Crime Prevention, 2004. http://www.unodc.org/pdf/crime/seventh_survey/7sc.pdf (accessed 27 October 2007). [ Links ]

14. Reza A, Mercy JA, Krug EG. Epidemiology of violent deaths in the world. Inj Prev 2001; 7: 104-111. [ Links ]

15. Lumpe L. The regulation of civilian ownership and use of small arms. Geneva: Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, February 2005. www.hdcentre.org/datastore/Small arms/Rio_ briefing_final.pdf (accessed 27 October 2007). [ Links ]

16. Hirschi T, Gottfredson M. Age and the explanation of crime. Am J Sociol 1989; 83: 552-584. [ Links ]

17. World report on violence and health; youth violence. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002. [ Links ]

18. Meel BL. Incidence and pattern of traumatic and/or violent deaths between 1993 and 1999 in Transkei region of South Africa. Am J Trauma 2004; 57(1): 125-129. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

B Meel

(bmeel@wsu.ac.za)

Accepted 11 October 2007.