Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versão impressa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.98 no.5 Pretoria Mai. 2008

SCIENTIFIC LETTERS

Survival after massive intentional overdose of paraquat

Umesh G LallooI; Anish AmbaramII

IMD, FCCP, FRCP (London); Department of Pulmonology and Critical Care, Department of Medicine, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban

IIMB BCh, FCP (SA), Cert Pulm (SA); Department of Pulmonology and Critical Care, Department of Medicine, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban

To the Editor: Survival following oral ingestion of a large volume of paraquat is rare. Our patient ingested approximately 200 ml of paraquat and survived, following aggressive intervention. He developed oral pharyngeal ulceration, acute lung injury, haematemesis, haemoptysis and renal failure. He was treated with a combination of pulse methylprednisolone, vitamins C and E, and N-acetylcysteine. We propose a rationale for high-dose antioxidant treatment in addition to corticosteroids and intensive care.

Case report

A 20-year-old man was referred to our critical care unit 16 hours after the intentional ingestion of several mouthfuls of paraquat (1,1'-dimethyl-4,4'-bipyridinium dichloride (Gramoxone; Syngenta, Namibia)), taken directly from a 5-litre container. He vomited approximately a cupful of blood several hours after the ingestion, and vomited greenish fluid several times thereafter. He was given milk by his family, taken to a local hospital and transferred to our care.

On admission the patient was lucid and had normal levels of arterial blood gases. His blood pressure was 130/70 mmHg, his pulse rate 80 beats/min and his respiratory rate 20/min; urea, creatinine and electrolyte levels were normal; the white cell count was 1.6x109/1; examination of the urine showed 2+ blood and protein; and the chest radiograph was normal. Serum creatinine kinase peaked at 532 U/l on day 3 (MB fraction 10%). Liver function was normal. His posterior pharynx was erythematous. Immediate management comprised 50 g activated charcoal 4-hourly per nasogastric tube until his stools were black (day 5), and intravenous 0.9% saline 80 ml/ hour.

Aggressive treatment was introduced in view of the grim prognosis. He was given intravenous methylprednisone 1 g stat and daily for 3 days, vitamin C 100 mg 4-hourly for 14 days, and an infusion of N-acetylcysteine at 150 mg/kg for 1 hour, 50 mg/kg over the next 4 hours, then 100 mg/kg daily for 4 days. Vitamin E, 50 mg daily, was commenced on day 5 for 12 days, when oral medication was possible after cessation of activated charcoal treatment.

Renal failure developed on day 2; haemodialysis was commenced on day 5 and continued up to day 15. The patient became tachypnoeic and hypoxic on day 3 and had bilateral chest crackles on auscultation. A chest radiograph showed bilateral mild infiltrates and he was given supplemental 40% oxygen via a facemask. Renal function returned to normal. His hospital stay was complicated by episodes of haemoptysis, nosocomial pneumonia on day 14, and right axillary and subclavian vein thrombosis on day 20 attributed to a central venous catheter. He was discharged on day 15 and continued on oral anticoagulant treatment.

Discussion

Survival following a massive overdose of paraquat is extremely rare. We used a combination of corticosteroid and antioxidant treatment on the hypothesis that mortality is due to respiratory failure and that the toxicity is primarily oxidant mediated. We were unable to measure paraquat levels as the recommended urine dithionite test for paraquat was not available at our institution. The volume of paraquat solution ingested by our patient was estimated to be about 200 ml (several mouthfuls). The lethal dose according to the manufacturer is 3 - 5 mg/kg (10 - 15 ml of the 20% solution). The history and clinical course of the patient conformed to massive ingestion of paraquat attenuated by the combination of intensive care and high-dose antioxidant and corticosteroid treatment.

Accidental paraquat poisoning is common globally because of its widespread use as a herbicide in agriculture. Systemic absorption usually occurs via exposed skin during spraying of paraquat. High-dose exposure occurs with oral ingestion, usually as a suicide attempt. Based on the low lethal dose, oral ingestion is almost invariably fatal because of progressive diffuse alveolar damage and rapidly progressive acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

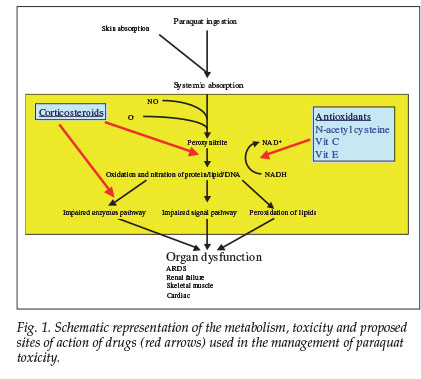

Approximately 20% of ingested paraquat is absorbed.1 An empty stomach and pre-existing gastrointestinal ulceration increase absorption. Toxicity is manifested by oedema and ulceration of the mouth, pharynx, oesophagus, stomach and intestines. Paraquat has multiple sites of toxicity. It is rapidly metabolised to peroxynitrite, the effects of which depend on the site of action as well as the levels of antioxidant achieved in vivo and duration of exposure.2 It is a strong oxidant and nitrating intermediate that reacts with proteins, lipids and DNA via direct or radical mediated mechanisms. This results in altered enzyme activities and signalling pathways2 and a major disruption of nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)-dependent cellular processes.3

The lungs are the primary target organ of paraquat toxicity and account for the mortality in most instances.4 Pulmonary damage is a result of oxidative stress to the alveolar epithelium which actively takes up paraquat (and its metabolites). Acute pulmonary oedema and early lung damage may occur within a few hours of acute severe exposure. Haemorrhage, proteinaceous oedema fluid, and leucocyte infiltration into alveolar spaces may occur, followed by rapid proliferation of fibroblasts.5 Delayed pulmonary damage resulting in pulmonary fibrosis occurs between 7 and 14 days after ingestion. Our patient appears to have had an attenuated delayed pulmonary reaction, probably as a result of the therapeutic intervention. He had several episodes of haemoptysis and mild pulmonary infiltrates that did not progress to florid respiratory failure and ARDS. Reversal of pulmonary fibrosis several months after ingestion of paraquat has been reported.5 Circulatory failure has also been reported in patients who ingested a large volume of concentrated (20%) solution. Shock and death within 48 hours of ingestion has been reported.4

As toxicity progresses, centrizonal hepatocellular injury may develop, manifesting as hepatocellular enzyme elevation and hyperbilirubinaemia. Renal toxicity may play an important role in determining survival because normal tubular cells actively secrete paraquat into the urine, thereby decreasing its toxicity. Haemodialysis was only introduced in our patient when renal failure manifested; he recovered renal function within 14 days.

Other sites of injury include skeletal and cardiac muscle, which manifests with elevated muscle enzymes. Our patient had a transient elevation in his muscle enzymes which peaked on day 3. We submit that muscle injury might have been attenuated by treatment.

The results of management of paraquat poisoning have been disappointing. These have included adsorbents, pharmacological approaches6 and radiotherapy,7 haemodialysis and haemoperfusion.8 Our patient's therapeutic regimen maximised antioxidant effects with available agents, including N-acetylcysteine based on the regimen for paracetamol overdose, vitamin C, and vitamin E. N-acetylcysteine significantly improves mortality in paraquat-intoxicated rats,9 and its use in lung disease was extrapolated from its application in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.10 High-dose corticosteroid treatment was determined from the study by Chen et al.11 Methylprednisolone improved histology but not oxygenation in a rat model of paraquat-induced lung injury.12 Other studies, however, have not shown improvement in histology and surfactant in rats that were pre-treated with methylprednisolone.13 Repeated pulses of methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide with continuous dexamethasone therapy showed a 54% improvement in survival (p=0.027) in patients with a 50 - 90% predictive mortality.14,15

Intravenous cyclophosphamide has been recommended,16 but we elected not to use it in our patient as it may be toxic and its therapeutic rationale is not clear. Decreased vitamin C and E levels have been demonstrated in rats after paraquat administration,17 and vitamin E has neuroprotective effects on rat striatal neurons after oxidative stress caused by paraquat, providing further rationale for the use of these vitamins.18 These antioxidants might have contributed to the treatment of oxidant stress associated with paraquat toxicity.

There have been no reports on the use of N-acetylcysteine together with methylprednisolone and other antioxidants such as vitamins C and E. We propose that our patient survived a potentially lethal dose of paraquat because of the massive doses of antioxidants administered. Fig. 1 outlines the rationale for our therapeutic intervention and the proposed mechanism of toxicity. Human studies are impossible, and prevention of paraquat toxicity is important. We recommend that large doses of antioxidants and corticosteroids are given empirically in the event of poisoning, which may also be a potential therapeutic strategy for acute lung injury of other causes.

References

1. Sittipunt C. Paraquat poisoning. Respiratory Care 2005; 50(3): 383-385. [ Links ]

2. Denicola A, Radi R. Peroxynitrite and drug-dependant toxicity. Toxicology 2005; 208(2): 273-288. [ Links ]

3. Suntres ZE. Role of antioxidants in paraquat toxicity. Toxicology 2002; 180(1): 65-77. [ Links ]

4. Bismuth C, Garnier R, Dally S, et al. Prognosis and treatment of paraquat poisoning. A review of 28 cases. J Toxic Clinic Toxicol 1982; 19: 461-474. [ Links ]

5. Giulivi C, Lavagno CC, Lucesoli F, et al. Lung damage in paraquat poisoning and hyperbaric oxygen exposure. Superoxide mediated inhibition of phospholipase A2. Free Radic Biol Med 1995; 18: 203-213. [ Links ]

6. Bateman, DN. Pharmacological treatments of paraquat poisoning. Hum Toxicol 1987; 6: 57-62. [ Links ]

7. Talbot AR, Barnes MR. Radiotherapy for the treatment of pulmonary complications of paraquat poisoning. Hum Toxicol 1988; 7: 325-332. [ Links ]

8. Hampson ECGM, Pond SM. Failure of hemoperfusion and hemodialysis to prevent death in paraquat poisoning: a retrospective review of 42 patients. Med Toxicol 1988; 3: 64-71. [ Links ]

9. Yeh ST, Guo HR, Su YS. Protective effects of N-acetylcysteine treatment post acute paraquat intoxication in rats and in human lung epithelial cells. Toxicology 2006; 223: 181-190. [ Links ]

10. Demedts M, Juergen B, Buhl R, et al. High dose acetylcysteine in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. NEJM 2005; 353(21): 2229-2242. [ Links ]

11. Chen CM, Wang LF, Su B, et al. Methylprednisolone effects on oxygenation and histology in a rat model of acute lung injury. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2003; 16(4): 215-220. [ Links ]

12. Chen GH, Lin JL, Huang YK. Combined methylprednisolone and dexamethasone therapy for paraquat poisoning. Crit Care Med 2002; 30(11): 2584-2587. [ Links ]

13. Chen CM, Su B, HSU CC, Wang LF. Methylprednisolone does not enhance the surfactant effects on oxygenation and histology in paraquat-induced rat lung injury. Intensive Care Med 2002; 28(8): 1134-1144. [ Links ]

14. Lin JL, Lin-tan DT, Chen KH, et al. Repeat pulse of methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide with continuous dexamethasone therapy for patients with severe paraquat poisoning. Crit Care Med 2006; 34(2): 368-373. [ Links ]

15. Lin NC, Lin JL, Lin-Tan DT. Combined initial cyclophosphamide with repeated methylprednisolone pulse therapy for severe paraquat poisoning from dermal exposure. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 2003; 41(6): 877-881. [ Links ]

16. Buckley NA. Pulse corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide in paraquat poisoning. (Comment.) Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 163(2): 585. [ Links ]

17. Ikeda K, Kumagai Y, Nagano Y. Change in concentration of Vitamins C and E in rat tissues by paraquat administration. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2003; 76(5): 1130-1131. [ Links ]

18. Osakada F, Hashino A, Kume T. Neuroprotective effects of alpha-tocopherol on oxidative stress in rat striatal cultures. Europ J Pharmacol 2003; 465: 15-22. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

U G Lalloo

(lalloo@ukzn.ac.za)

Accepted 3 December 2007.