Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versão impressa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.98 no.4 Pretoria Abr. 2008

FROM THE EDITOR

National health insurance on the horizon for South Africa

'Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health is the most shocking and the most inhumane.'

Martin Luther King Jr

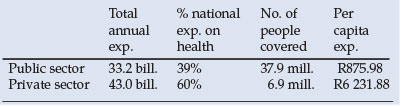

Twelve years into our 1994 democratic dispensation, South Africa remains one of the most unequal societies in the world, and nowhere is this more apparent than in our two-tier health system made up of an under-funded public sector serving the needs of the poorer 68% of the population, and a resource-guzzling private sector serving the rest. The private sector, operating in a weak regulatory context, is inclined towards excessive cost inflation while locked into a system offering declining benefits, in which the consumer has come to bear an increasing portion of the financial burden. The table below reflects the stark inequalities.

Ironically, the medical profession - which ought to be the backbone of the private sector - has not been the beneficiary of the skyrocketing costs of private care; on the contrary, doctors have witnessed significant erosion of their real income base over the years.

The public sector depends on budget allocations determined largely in the context of the budget process rather than any explicit policy or plan. The allocations do not take into account such factors as population changes (including immigration) and changes in morbidity patterns. Consequently, an over-resourced private sector is coexisting alongside a public sector characterised by declining health budgets in real terms, a growing burden of disease due to the HIV/AIDS pandemic, worsening health status indicators, the resurgence of communicable diseases and human resource shortfalls.

That the present health system is neither rational nor fair is widely recognised, and the real debate has been about how best to structure and fund an alternative health care system that is both equitable and feasible. As far back as 1944, the Gluckman Commission recommended the adoption of a fully tax-funded National Health Service akin to the NHS in the UK, with health services totally free at the point of delivery. The recommendation was never implemented.

The debate resurfaced in the mid-1980s through to the early 1990s among academic and political activists, but it was not until after the 1994 democratic elections and the accession to power of the ANC with its National Health Plan (NHP) calling for 'A single comprehensive, equitable and integrated National Health System' that the restructuring of the health system came to take centre stage in the corridors of power. The NHP proposed that 'a Commission of Inquiry be appointed by the Government of National Unity as a matter of urgency, to examine the current crisis in the medical aid sector and to consider alternatives such as a compulsory National Health Insurance (NHI) system . . . The Commission will investigate the appropriateness and economic feasibility of a National Health Insurance system within the South African context and undertake detailed planning for implementation of an NHI ...'

Successive committees of inquiry were accordingly empanelled to investigate the feasibility of such a scheme. Two versions of mandatory health insurance have emerged from the investigations: a Social Health Insurance (SHI) scheme that would be mandatory for a specified group (such as those in formal employment earning above a prescribed threshold), and a compulsory universal National Health Insurance (NHI) scheme that would cover all South Africans.

Current thinking appears to favour the implementation of SHI in the first instance, but only as a stepping stone towards the ultimate goal of a universal NHI. According to the HSRC's Olive Shisana, 'The NHI system presents itself as an ideal mechanism for achieving equitable access to quality health services in South Africa: firstly, because it satisfies the fundamental principles of a unitary health system ... enshrined in our constitution; secondly, because it promotes redistribution and sharing of health care resources between the public and private sectors thus meeting our transformation agenda; thirdly, because research evidence suggests that South Africans are generally willing to contribute to a financing system that caters for them and those unable to contribute.'

However, the implementation of NHI will be easier said than done. There are any number of imponderables to be sorted out in the design and eventual implementation of NHI, not least of which is the human and managerial capacity that will be required to support a scheme of this magnitude and complexity. This is not to pour cold water on the idea of mandatory health insurance. The present dichotomous health system is unsustainable financially and untenable in human rights terms. If NHI can overcome the inefficiencies of the private sector with its failing medical aid funding arrangement, and if it can address the quality-of-service issues of the public sector, it will indeed be a winning formula.

Daniel J Ncayiyana

Editor

danjn@telkomsa.net