Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Missionalia

versão On-line ISSN 2312-878X

versão impressa ISSN 0256-9507

Missionalia (Online) vol.50 spe Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.7832/50-1-460

ARTICLES

The search for Ikhaya. Can we build a Home together?

JNJ (Klippies) Kritzinger1

ABSTRACT

The search for a new social contract in South Africa is explored in this paper by examining the terms ikhaya and oikos, and the notion of covenanting together to build a home across the fault lines that divide society. It uses a seven-point praxis matrix to reflect on the way in which a group of theologians could covenant together to overcome the fault line of racism to build a 'deracial' home. The paper explores the role that each of the seven dimensions of praxis (agency, spirituality, interpreting the tradition, discernment for action, contextual understanding, and ecclesial scrutiny) should play in such a journey.

1. introduction

This paper is shaped by three assumptions underlying the theme of the 2022 conference of the Southern African Missiological Society (SAMS), "Reimagining a new social contract in the public space: Missiological contributions to the discourse." Those assumptions can be paraphrased as follows: a) Deep problems and challenges are facing South African society; b) There is a need for a broad-based initiative to imagine a new social contract; and c) Religious and theological communities have the responsibility and resources to contribute to such a reimagining.2

1.1 Ikhaya/oikos

My approach to the conference's theme does not focus on a social contract but a social covenant, and I link it to the idea of jointly building a home (ikhaya, oikos). I draw my inspiration mainly from Vuyani Vellem and Jonathan Sacks. I do not look at "social covenant" and "home" as abstract concepts; instead, I explore the praxis of social covenanting to explore how as theologians we could address the numerous fault lines running through society - and through our midst as theologians. I examine the kinds of encounters we need to have with each other if we are to imagine - and build - a home together.

My title, The search for Ikhaya, comes from the work of our late colleague, Vuyani Vellem.3 He wrote a Master's dissertation in 2002 at UCT entitled, "The quest for ikhaya: The use of the African concept of home in public life," in which he combined an action research project in Kayamandi with Black Theology. He engaged the US theologian William Everett's use of the oikos model and covenanting together in public life, relating that to the actual situation of urban black people. Vellem (2002:12) wrote:

The thesis of the quest for ikhaya is that urban blacks, broadly speaking, linger in a limbo (locations or townships) between a religious cosmos [the kraal, ubuhlanti] and a white city... The significance of ubuhlanti is its sacred place as a shrine of a home, ikhaya... As Bollnow ... magnificently puts it: 'to build a house is to found a cosmos in a chaos.' The cosmos that has been founded in the township limbo and the manner in which it has been negotiated and struggled for is a significant terrain for Black theology and public life in South Africa.

Vellem asserted that ikhaya was resilient in its struggle for survival in the "township limbo" of ikassie4 despite the "fierce scene of piercing holes into ikhaya" by colonial conquest, the Land Acts and apartheid laws. It has managed to survive against that "ferocious, coercive disintegration" and generated a hope "that knows that there is ikhaya and that ikassie is not ikhaya" (Vellem, 2002:134). For him, ikhaya speaks of wounded-but-resilient humanity and ubuntu that has not succumbed to ubolikishi (the distorted non-culture of ikassie).

I use the concept ikhaya/legae5with respect, not in an act of cultural appropriation,6 but to value and affirm the way in which Vellem (and many others) has asserted the central role of cultural identity in the struggle for dignity and jus-tice.7 At the same time, I use the term with shame at what my colonial forebears and apartheid contemporaries did to "pierce holes" into the fabric of African family and community life. I integrate the African concept of ikhaya/legae with the concept of oikos (household), found in New Testament Greek, to develop a cultural-theological framework that could contribute to a new "social contract" in South Africa.

The Greek term oikos is linked etymologically to economy, ecology and ecumenism. While focusing on the economy, the document The Oikos Journey affirmed that these three areas are also linked theologically and belong intrinsically together:

The word 'ecumenical' carries with it some of the meaning of both economics and ecology. God has created this 'house' and is busy at work seeing to justice and equality, reconciliation and the flourishing of all creation. The church, the 'household of God' is called to be a community of faith showing God's purposes in creation as a sign to others, through seeking not just the unity of Christians, but of all the people of the earth (Diakonia Council of Churches, 2006:25).

Affirming this view, I regard oikos as a helpful concept for a sense of mission in relation to the search for a new social contract.8 Therefore, I combine ikhaya and oikos in this paper with the hope that this approach can assist us in imagining a just and inclusive home that will give all of us a deeper sense of identity and belonging.

1.2 Mission praxis

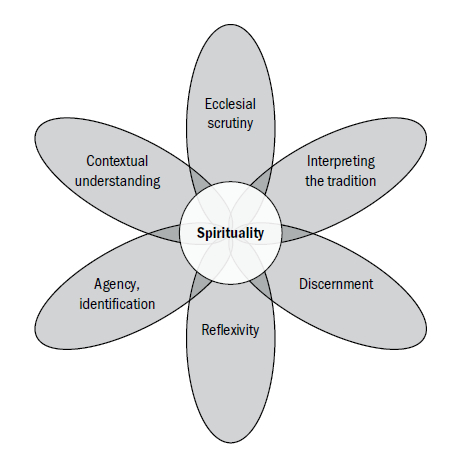

My understanding of mission is in basic agreement with Bosch, that God's mission is a "multifaceted ministry," encompassing dimensions such as "witness, service, healing, reconciliation, liberation, peace, evangelism, fellowship, church planting, earth-keeping, and much more" (Bosch, 1991:512). In other words, acts of covenanting together for social justice and building society as an inclusive home are integral dimensions of God's mission. Since all such forms of mission praxis are aimed at some kind of transformation and involve encounters, my definition of mission also includes the notion of transformative encounters in which Christians are actively engaged. I use the following matrix to explore forms of mission praxis, which in this paper is covenanting together to build society as a shared home of justice and peace (see Kritzinger & Saayman 2011:3-6).

The praxis matrix can be used in two ways: either as a mobilising instrument to initiate and direct transformative actions or as an analytical instrument to study the transformative actions of others and the encounters between them. In this paper, I use it as a mobilising tool to imagine the kind of interactions we need to have with each other if we wish to have a transformative impact on society. This matrix requires that we ask seven questions about every form of praxis:

• Agency: Who are the actors?

• Contextual understanding: How do they analyse their context?

• Ecclesial scrutiny: What role have churches played in the past in that context?

• Interpreting the tradition: How do the actors interpret Scripture and tradition?

• Discernment for action: What actions or projects do they undertake?

• Reflexivity: Do they reflect on their actions and change course where needed?

• Spirituality: What experience of God sustains their actions?

That makes it possible to explore how different praxes encounter each other and become transformed. I return to the matrix's seven dimensions later, but I first need to explain my use of the term praxis. There is a broad spectrum of meanings attached to the concept, ranging from one extreme of using it as a "trendy alternative to the words practice or action" (Bevans, 2002:71, italics in the original) to another extreme of a neo-Marxist use associated with political liberation and "left-wing revolutionaries" (Gordon, 2015:3). Bevans (2002:71) explains the genealogy of the term in recent thinking:

Praxis is a technical term that has its roots in Marxism, in the Frankfurt school (e.g., J. Habermas, A. Horkheimer, T. Adorno), and in the educational philosophy of Paulo Freire. It is a term that denotes a method or model of thinking in general, and a method or model of theology in particular.9

Bevans (2002:77) points out that a praxis perspective is not necessarily "narrowly Marxist" or limited to political liberation theologies, even though an emphasis on social change and transformation in a specific context is intrinsic to it.10 What distinguishes it from other approaches is its method of action-reflection that affirms "the unity of knowledge as activity and knowledge as content" (Bevans, 2002:72).

My own use of the term praxis avoids using it as a mere synonym for practice or action. Instead, praxis refers to a method of acting-thinking-acting that affirms the ongoing interplay between action and reflection, analysis and planning, prayers and practices, and therefore encompasses various interacting dimensions, as expressed by the praxis matrix.

Additionally, praxis refers to actions that are transformative or at least intentionally transformative. This is the Marxian aspect of my understanding of praxis, following the often-quoted adage of Marx that philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways, but that the point is to change it (Marx & Engels, 1968:30). Where my view of praxis does not follow Marx is that I use it to describe various forms of transformative activity, not only activities towards social justice and political-economic liberation. I contend that evangelism, church planting, earth-keeping, reconciliation, etc., can all be seen as forms of praxis since they all aim at achieving (some kind of) transformation and since all seven dimensions of the matrix can be identified in how they operate. My view also deviates from Marx in that I do not share his Promethean, modernist trust in the human ability to "change the world." The praxis I am talking about is less pretentious; it is human participation in God's work of changing the world.

My approach of not limiting the term praxis to liberation projects has an ecumenical intent, namely to create common ground for meaningful interaction between missiologists who differ from each other in terms of theology, ideology, spirituality, race, culture or gender. If we all ask the seven questions in the matrix about our own praxes, we not only become more reflexive ourselves, but also more sensitive to the shape of other people's praxes and better able to notice where we differ from them - and what we need to work on if we wish to covenant together with them. Therefore, I suggest that covenanting together for justice can be portrayed as encounters between different praxes, across all the cracks that divide us, in which we dig deep within ourselves to discover and affirm who we are and what moves us - and then also reach outside of ourselves to engage in honest encounters with others.

1.3 Identifying the fault lines

At least six intersecting cracks run through South African society, shaping our agency as theologians. We are different in terms of race, gender, language and culture, theological tradition, economic status, country of origin and sexual orientation. Yet, we are the same since we all identify as Christian theologians. So we form a large "US" - all of us together - and several smaller "usses" - overlapping subgroups along the fault lines I have identified. As theologians, we cannot contribute to a movement of social contracting or covenanting in South African society at large if we cannot practise such covenanting among ourselves, which is the focus of this paper.

It is not possible to address each of the six fault lines separately. Instead, this paper only develops a process of transformative covenanting in relation to the fault line of racism, while pointing out at the end how it could be applied to other fault lines.

2. Covenanting Together To Build A Deracial Home

A key aspect of building a just and transforming home is overcoming the destructive power of racism. I use the term deracial, following the pattern of decolonial, as the goal of our journey, but to get there, I believe we should adopt anti-racist strategies. Race is fiction, but racism is real. If we use the term race, we must affirm that there is only one race - the human race. At the same time, we must admit that our identities have become racialised, thereby making racism a reality. To decolonise our minds and societies means to deracialise them. We need to un-think11 race while taking racism seriously as a persistent and destructive ideology. It is possible to reinforce racism by ignoring it in a "colourblind" non-racialism, but it can also be reinforced by essentialising race. To avoid these (and other) traps, my proposal involves an intentionally shared journey to deracialise our identities as we build a home together. In the words of Willie James Jennings (2020:44), this is a journey towards communion as "the working and weaving together of fragments in the forming of life together." When using the praxis matrix as a mobilising instrument, the journey to overcome racism begins with agency.

2.1 Agency

Many people need to be involved in reimagining this country's social, economic and political fabric. However, I limit myself to covenanting praxis among academically trained theologians. We make up a small percentage of South African society, so our impact is limited, but I have chosen to focus on us - who we are and what we are able to do - rather than to reflect abstractly on the situation at large, or on what others ("the government," "the politicians" or "the church") should do. Instead, I am proposing the kind of conversations we, as academic theologians, could have with one another to address the challenges facing us.

The agency dimension forces everyone to reflect on their own agency (how they perceive themselves and where they are coming from) and understand where others are coming from. This exposes the false perception that there is theology - and then there is Black Theology. The irreplaceable value of a liberation theology like Black Theology is that it unmasks the pseudo-innocence of a white theology that does not acknowledge its social and racial position, biases and privileges. It forces everyone to start reflecting on the implications of its social, economic and political location - and, therefore, the nature of its being and acting. Richard Kearney (2015:138) tells how his mentor Paul Ricoeur used to greet students at a seminar with the question, dou parlez-vous? (Where are you speaking from?). The agency dimension of the matrix calls us out of theological generalisations and universals to come to terms with who we are - and to admit that it matters deeply - as we enter a transformative journey of covenanting together to build a shared home.

Concerning my personal location and agency in relation to the struggle against racism, let me just say that what I am doing here is in continuity with my publications since my doctoral thesis (Kritzinger, 1988). It is also based on years of engagement with members, ministry students and colleagues in the Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa (URCSA), through which I have become painfully aware of the deep cracks running through our society, but also convinced of the real possibility of overcoming them by covenanting together in Christ.12

2.2 Spirituality

Since my understanding of mission centres around transformative encounters, I must stress that the most crucial encounter in mission is the encounter with God. Spirituality is at the heart of the praxis matrix to affirm that encounters with God intrinsically shape all the dimensions of praxis. We see this foundational encounter in the call narratives of Abraham (Gen. 12:1-3), Moses (Ex. 3:1-15), Isaiah (6:1-13), Jeremiah (1:4-10), Peter, James and John (Lk 5:1-11) and Saul of Tarsus (Acts 9:9-19), to mention only the clearest examples. If it is true that mission is God's initiative and that we are called to participate in the missio Dei by the Holy Spirit, then we need to affirm that God also has a praxis; that God is actively at work in us and amongst us as God draws us into a liberating mission. This means that the encounters between our human praxes occur not only as commanded or empowered by God, but also as encounters with God - literally in God's presence, before God's face, to use an Old Testament expression.

The words of the apostle Paul in 2 Cor. 2:17 are relevant here.13 To defend and define his apostleship, he says, "For we are not peddlers of God's word like so many; but in Christ we speak as persons of sincerity, as persons sent from God and standing in his presence." The apostle's witness is not about "peddling" God's message (doing business to make a profit).14 Instead, it is shaped by an "unmixed" sincerity15 and a spirituality of honest speaking that is qualified in three ways: "in Christ," "from God" and "before God."16 The important point here is that in authentic transformative praxis, God's praxis is both behind us (sending us) and before us (leading us, going before us, confronting us, challenging us, holding us accountable). The latter emphasis is essential to prevent a triumphalist sense of sent-ness that assumes a kind of monopoly on God, that God is always behind us, on our side, blessing us, empowering us to teach or "convert" others. This is the distorted missionary Christianity born in and with European modernity, from which we need to be liberated. It is Christianity (and theological education) that cultivated "the self-sufficient white man" who is "the man who serves" (Jennings, 2020:46, 74) and that keeps on creating others in his image.

What makes praxis Christian is that it takes place "in Christ," which means "existential participation in the new reality brought about by Christ" as crucified-risen Lord, "Paul evidently felt himself to be caught up 'in Christ' and borne along by Christ. In some sense he experienced Christ as the context of all his being and doing" (Dunn, 1998:400). However, it is crucial not to misunderstand "in Christ" in an individualist way. On the contrary, it is an inherently communal or collective term in Paul's letters, so Dunn (1998:401) speaks of "a community which understood itself not only from the gospel which had called it into existence, but also from the shared experience of Christ, which bonded them as one." What Paul's mission praxis "in Christ" entails is evocatively expressed by Theodore Jennings (2013:218):

His [Paul's] is an explicitly messianic movement that supposes that God's purpose of a truly just social order has been inaugurated in the messianic event of Joshua's17 mission, execution, and resurrection. I recall Steve Biko in South Africa saying that it is not a matter of organizing a movement to bring about liberation but of preparing people for the liberation that is coming... If there are communities of generous welcome that exhibit a new sort of justice outside the law within the empire, then this is enough to demonstrate that the days of that empire are truly numbered.. He is not interested simply in giving people the right ideas but in enabling them to become mini-societies of messianic justice. He has no particular interest in cult or even the fine points of doctrine but in forms of social life that reflect the coming justice of God.

In other words, when we think of the collective dimension of praxis "in Christ," we should not immediately think "in church" - at least not in the sense of an established church - but rather of "mini-societies of messianic justice" that Theodore Jennings describes as "communities of generous welcome," representing a "radically egalitarian sociality," in which:

There is to be a remarkable intimacy among members of the same cell and between members of different cells, composed of different sorts of people, united in messianic hope and in the project of living out already in the now-time a form of life in dramatic contrast to the old social order out of which they have been called (Jennings, 2013:228).

The messianic praxis modelled by the apostle Paul fosters life-changing encounters that create a community reflecting the coming justice of God and living in God's presence. That implies placing spirituality at the heart of a praxis cycle or matrix. If we want to covenant together as Christian theologians for the transformation of our society, we need to learn how to speak to each other "in Christ" as "persons of sincerity ... sent from God and standing in God's presence," becoming mini-societies of messianic justice.

This does not mean that we enter into a separate spiritual zone, sanitised from our real lives. Placing spirituality at the heart of the matrix does not mean that formal piety or contrived religiousness controls every dimension of praxis. It means that our activities (and activism) for social justice and transformation should be rooted in an awareness of God's active and liberating presence amongst us so that we march to a different drum in our efforts as Christians - and with people who are not - to participate in God's mission of building a shared home.

2.3 Interpreting the tradition

What would be the theological resources for covenanting to build a deracialised home in the light of this messianic praxis? This is a vast topic, so let me pick up only a few pointers.

2.3.1 The quest for a true humanity

A good point of departure is the statement of Vuyani Vellem (2017:5) on what is necessary for a "healthy conversation" between black and white theologians:

For the liberation of white people to be possible, white consciousness is crucial to deal with. Understanding whiteness and the privilege attached to it in a society set up to benefit white people at the direct expense of black people is an important starting point. Once white people come to such an understanding and listen to the comprehensive argument by BTL [Black Theology of Liberation] prior to negating it, or defending their actions, a healthy conversation is sure to unfold.

This proposal contains three moves: a) From the side of black theologians, a comprehensive liberating argument (BTL); b) From the side of white theologians, an understanding of white privilege and an honest listening to the BTL argument; and c) an unfolding (ongoing) healthy conversation between black and white people that makes the liberation of white people possible. This is similar to the dialectical journey proposed by Steve Biko (1978:90):

For the liberals the thesis is apartheid, the antithesis is non-racialism, but the synthesis is very feebly defined. They want to tell the blacks that they see integration as the ideal solution. Black Consciousness defines the situation differently. The thesis is in fact a strong white racism and therefore the antithesis to this must, ipso facto, be a strong solidarity amongst the blacks on whom this white racism seeks to prey. Out of these two situations we can therefore hope to reach some kind of balance - a true humanity where power politics will have no place.

I will discuss this dialectical encounter in more detail later, but I first need to explore the goal of this journey. The envisaged liberation or integration is described as true humanity, about which Biko (1978:108) also said:

We have set out on the quest for true humanity, and somewhere on the distant horizon we can see the glittering prize. Let us march forth with courage and determination, drawing strength from our common plight and our brotherhood. In time we shall be in a position to bestow upon South Africa the greatest gift possible - a more human face.

Elsewhere Biko broadened this into a global perspective, "[T]he great gift still has to come from Africa - giving the world a more human face (Biko, 1978:51, italics added). Neither Biko nor any other black theologian underestimated the obstacles facing that march to the glittering prize. He paid the highest price for his courage and determination to lead it, setting that goal before us.

2.3.2 Metamorphosis

To fathom the depth of the challenge facing us, we need to hear the voice of Mahmood Mamdani (1998:3):

In the context of a former settler colony, a single citizenship for settlers and natives can only be the result of an overall metamorphosis whereby erstwhile colonizers and colonized are politically reborn as equal members of a single political community. The word reconciliation cannot capture this metamorphosis [ ... ] This is about establishing for the first time, a political order based on consent and not conquest. It is about establishing a political community of equal and consenting citizens.

This statement clearly elucidates the glittering prize and the challenge of getting there. Since the personal (and the theological) is political, this is the challenge facing us as black and white theologians, namely undergoing a political-spiritual-theological rebirth to establish, for the first time, a political order in theology based on consent, a political community of equal and consenting theologians. The assumption behind this image is that "settler" and "native" cannot be reborn separately, in isolation from each other. What will make it a metamorphosis, and not a mere exercise in reform or renewal, is when black and white theologians are reborn together through a process of in-depth encounters. In a later publication, Mamdani (2021:195) extends his critique of fixation on the settler/native binary to the victim/perpetrator binary, suggesting the notion of a survivor instead. It is not simply a victim of the catastrophe who did not die, "A survivor is anyone who experienced the catastrophe. All must be born again, politically." This use of religious and theological terms like metamorphosis and rebirth by a Muslim political scientist is not only a reflection of the enormity of the challenge but perhaps also a confession that divine assistance is necessary to make it happen.

In different words, Vellem (2017) also believed that a deracialising metamorphosis could happen. He regarded it as possible for a White Theology of Liberation to unfold in response to a Black Theology of Liberation (BTL), "with a view ultimately to finding ways in which a synthesis between black and white theologies could be developed" (Vellem, 2017:4). The challenge is to find concrete ways in which a WTL could develop alongside and in dialogue with BTL so that a shared metamorphosis can begin to take shape.

The "new birth" dimension of this metamorphosis is highlighted by van Wyngaard, who entitled his thesis, In search of repair. He explained the title as follows:

What . theological work does is not to bring repair itself, but to clear the space so that God can do the work of repair... [R]epair is the work of the Spirit ... and reparative writing is to recommend ways of removing obstructions to the work of the Spirit, rather than ways of directly repairing loss (van Wyngaard, 2019:150).18

This again underlines the central role of spirituality in transformative, liberating praxis.

2.3.3 Building a home together

I have already referred to the metaphor of society as a building constructed by citizens together. The former chief rabbi of London, Jonathan Sacks, wrote a book entitled, The home we build together: Recreating society (Sacks, 2007). I pick up only a few of his key ideas that are relevant here. Firstly, he argues that a social contract can create a state but that only a social covenant can create a society. For Sacks (2007:94), the real challenge facing "liberal democracy" in Britain and elsewhere in the world is about society, not about the state:

It is not about power but about culture, morality, social cohesion, about the subtle ties that bind, or fail to bind, us into a collective entity with a sense of shared responsibility and destiny.

Sacks argues that a healthy society needs a sense of common belonging, contrasting three dwelling types as metaphors. First, there is a manor house, an image of an ethnocentric society shaped by the identity of a ruling class, where minorities (like servants) must assimilate if they wish to belong. Second, there is a hotel, an image of multiculturalism, where there is no shared belonging, only individuals living in separate rooms, with no values in common and no real interest in the common good (Sacks, 2007:95). Finally, there is a home, a community based on covenantal loyalty, with shared values drawn from the Hebrew Bible, such as human dignity, freedom, the role of civil society and respect for diversity. Quoting Joseph Allen's view on a covenantal model of Christian ethics, he says:

To be in covenant with other people involves believing that we and they belong to the same moral community; that in this community each person matters in his or her own right and not merely as something useful to the society; that we all participate in the moral community by entrusting ourselves to others and in turn by accepting their entrusting; and that in the moral community each of us has enduring responsibility to all the others (Sacks, 2007:101).

Sacks points out that the ideals which create a society, such as justice, compassion, human dignity, welfare, relations between employer and employee, the equitable distribution of wealth, and the social inclusion of those without power (widows, orphans, strangers) require a distinctive logic, "To these issues, social contract is irrelevant. What matters is social covenant" (Sacks, 2007:106). He identifies three approaches to social life and the logic of association, namely state, market and covenant:

Covenant complements the two great contractual institutions: the state and the market. We enter the state and the market as self-interested individuals. We enter a covenant as altruistic individuals seeking the common good. The state and the market are essentially competitive. In the state we compete for power; in the market we compete for wealth. Covenantal institutions are essentially co-operative. When they become competitive, they die (Sacks, 2007:234).

His conclusion is, "Society is the home we build together" (Sacks, 2007:231). One could ask whether his distinction between state, market and (civil) society is perhaps too sharp, but his point about "recreating society" through social covenanting is highly relevant to addressing our challenges.

2.3.4 The epistemological architecture of a shared home

When one speaks of building a home, you are talking about architecture. How do we imagine the design or shape of the home we want to build together? Bollnow (Vellem, 2002:7) states, "To build a house is to found a cosmos in a chaos." That is reminiscent of the creation narrative in Genesis 1, where it is said that God placed a dome or firmament (Hebrew: raqi'a) in the midst of the watery chaos to create dry ground for an orderly cosmos to emerge. That protective dome expresses God's power over chaos and God's caring authority over creation. On the sixth day, God created men and women as image-bearers to share in that caring authority: to live under God's protective blessing and, in turn, be a protective blessing to all that lives. However, when everything went wrong, and evil proliferated, God allowed the dome to collapse and water from above and below to engulf the earth in a flood. When the water had receded, God made a covenant with Noah, with the earth and all living things, promising that the dome would never collapse again and giving the rainbow as a sign of that promise. The message of the rainbow in Genesis 9 is not in its colours, but in its shape: it proclaims the dome of God's caring, protecting authority, under which humans, animals and the earth are promised God's blessing. If that is the architecture of God's creative and providential care, by giving all living creatures a safe home to inhabit, this could also be the imaginative shape of the home we build together.

This has two implications. Firstly, all authority is God's authority - it is a dome-shaped, caring, blessing authority. Our authority in the midst of creation dare not become oppressive; we are merely stewards, caretakers, and vice-regents under God. We uphold God's authority by holding up the dome, women and men together. Therefore, all authority - in family, church, school, university, market, and parliament - should be dome-shaped, rather than triangular and hierarchical.19

Secondly, when we hold up the dome together, we find ourselves standing in a circle, which is a unifying and harmonising image. Vellem (2017:7) honoured the African womanist theologian Mercy Amba Oduyoye and the Circle of African Women Theologians by saying:

A circle is deeply symbolic in African architecture and thus epistemological architecture in contrast to straight lines. The West chooses violence, to eliminate rather than bring in! ... The lived experiences of the colonised simply show that at the heart of the Western ways of knowing and thinking, elimination rather than persuasion is core.

A home built on mutual persuasion and the "harmonising of difference" can only be imagined as round, perhaps in the form of a domed AmaZulu hut. It should embody the African womanist approach, which prefers coaxing to "dualism, abrasion, imposition and offense" ... and is committed to "coaxing their male counterpart to life-affirming relationships" (Vellem, 2017:7). Such a round-tabled "art of deliberation," which is also affirmed by feminist theologians like Letty Russell (1993) and Rebecca Chopp (1998:303), could shape the epistemological architecture of the home we build together. It embodies the spirituality of Sarah's circle rather than Jacob's ladder (Fox, 1999).

The domed firmament of God's powerful and caring authority in creation (Genesis 1 and 9) is also evident in the reign of God proclaimed and embodied by Jesus. By conquering chaos and evil through Jesus, God creates space for life in fullness, calling forth a circle of disciples who hold up the dome together to become a "church in the round" and a "household of freedom"20 (Russell, 1987).

2.4 Discernment for action

What would it look like if black and white theologians covenant together for a de-racial future under the dome of God's caring authority? What kinds of actions and processes will it require?

2.4.1 A journey of love

In Christian theology, such a transformative journey can only be conceived as a journey of love. Not an individualised and sentimentalised love, but a strong-and-tender love with a public face. As Cornel West (2018) stated, "Justice is what love looks like in public; tenderness is what love looks like in private." It is also helpful to distinguish four postures or dimensions of love:21

• Face-to-face (dialogue): listening and talking to each other, building understanding and trust;

• Shoulder to shoulder (partnership): facing in the same direction, working together for the same goals;

• Back to back (integrity): remaining loyal to each other and not betraying the trust growing between us when we are apart;

• In front and behind (maturity): taking turns to be in front; having the humility to lead and the courage to follow.

These postures are not alternative relationships, but complementary and alternating dimensions of a growing relationship conceived as a journey. When linked to the view of Vellem mentioned in 2.3.1, such a transformative journey of black and white theologians can be understood (and organised) as a series of alternating encounters.

Firstly, there should be parallel meetings in which we, as black and white theologians, meet separately to reflect on deracialising praxis in and for ourselves and our respective black and white communities, exploring the kinds of metamorphosis we need within and amongst ourselves. Biko argued that, since faith was needed to "win battles," it was essential that "our faith in our God is [not] spoilt by our having to see Him through the eyes of the same people we are fighting against." He thereby signalled the need for a Black Theology committed to "restoring a meaning and direction in the black man's understanding of God" (Biko, 1978:60) and overcoming the "flight from the black or African sell5' (Tshaka, 2009:156-164; 2010:124; 2014:3). Similarly, white theologians need to overcome the flight from the white self, owning up to the image of the "self-sufficient white man" (Jennings, 2020:46), coming to terms with who we are, what we have done, and where we are going.

These are parallel face-to-face processes within the context of smaller "us" communities, but which face in the same direction, having the same (shoulder to shoulder) orientation towards building the encompassing "US" of true humanity. Neither of these "small-us" gatherings would be liberating if they were facing away from the other. That would not be new; such separateness is the status quo. What makes praxis liberating is its orientation towards Steve Biko's glittering prize of a shared true humanity on the horizon.

Secondly, there should be joint meetings (face-to-face) in the larger "US" community to share what we discovered "on our own" and to explore the kinds of metamorphosis needed between us and in our relationships. In these larger face-to-face encounters, we share insights and grow in confidence to affirm, question, confront and persuade each other. It is necessary to do theological reflection jointly to unthink race because the "fantasies" of blackness and whiteness were both produced by the same "wound" (Mbembe, 2017:39). We need to probe the "wound" that produced us "as black and white, as racial beings in a racist world" (Van Wyngaard, 2019:4).22

Thirdly, there is a return to the parallel meetings of black and white theologians for further engagement and deeper reflection on our liberating theologies for the black and white communities. If such an iterative pattern of meeting apart and together continues, opening and closing like a pair of scissors, it can become a movement that produces a gradual deracialising metamorphosis, building the "synthesis between black and white theologies" that Vellem envisaged. It aims to be a journey of deracialising convergence between BTL and WTL in a joint struggle to overcome every form of racial exclusion, disrespect and oppression, in search of repair for our broken humanity.23

The parallel meetings of black and white theologians are not expected to produce monolithic black-and-white consensus positions to "bring back" to joint sessions. On the contrary, they are intended to stimulate deep reflection and honest interaction, likely to produce a range of views, not unanimity. To strive for a separate black-or-white consensus would undermine the very logic of this journey since it would perpetuate "us-them" positioning instead of "us-US" covenanting. It would mean that the "us" groups are not facing in the same direction when they meet apart but are facing away from each other and reinforcing entrenched racialised positions. Such attitudes will prevent the required metamorphosis of being "politically reborn as equal members of a single political community" (Mamdani). Willie James Jennings (2020:19), speaking about theological education, envisages a similar covenanting journey:

What is needed is a new motion that turns ... institutional energy toward life together in three crucial ways: (1) How we move into each other's lives, that is, how to think a good assimilation; (2) How we move inwardly and outwardly, that it, how we enact a healthy inwardness; and (3) How we move in new directions, that is, how we enact radical change and the overturning of the prevailing order.

This metamorphosis is a lifelong journey since we have much to unlearn and un-think as black and white theologians. However, it is possible to stop thinking and talking about racialised others as "them" - either for them or against them - and genuinely begin to think and talk with one another as "US" in a transformative way. Vellem (2015:7) set out the parameters of such a process by saying that an African epistemology is guided by the dictum "I know because we know." He added that "persuasion is the way of harmonising difference."

In all these encounters, spirituality has to play a key role. As suggested in 2.2, we need to meet sincerely in Christ, from God and before God to situate our encounters firmly within God's redemptive mission. A spiritual dimension does not make our interactions soft and woolly or move us to "paper over the cracks" with escapist spiritual exercises; instead, it deepens our awareness of "where God stands" in the situation (Belhar Confession, article 4) and what it means to "stand where God stands" as cross-bearing disciples of the crucified Christ, among the crucified people (Mofokeng, 1983; Buffel, 2015).

Having explained face-to-face and shoulder-to-shoulder, let me add that the back-to-back dimension of love should play a role throughout the process. It emphasises that partners who start trusting each other by engaging in "large-US" face-to-face encounters dare not betray that trust when they are "back at home" in a "smaller-us" context, by forgetting or insulting their encountering partners or by compromising with separatist sentiments among their "own people." Metamorphosis means rebirth into "unmixed sincerity" (2 Cor. 2:17) and integrity, growing together into true humanity.

2.4.2 Power relations

On such a deracialising journey, we dare not ignore the power differentials between the participants by assuming a horizontal relationship between black and white theologians (and theologies). For a long time, our relationships will remain diagonal, with one partner having more power and influence than the other in some respects. For example, a BTL has a much more developed praxis than WTL, which is, in many ways, a marginal phenomenon among white theologians.24 In that sense, white theologians have more to receive than to give in the "large-US" encounters. In addition, in the struggle against racism, the theological initiative and leadership must rest with black theologians since deep transformation can only proceed from below, from victims and survivors.

On the other hand, white theologians, having grown up in white privilege, often have more financial and infrastructural resources than black theologians, thus giving us more power in the relationship in those respects. For an iterative journey to be transformative, these power issues need to be acknowledged and addressed so that BTL and WTL not only gradually converge but that, at the same time, the "playing field" on which we meet is levelled.

As the playing field becomes increasingly levelled, a healthy and natural differentiation could take place, in which the fourth posture of love will emerge, namely black and white colleagues taking turns leading and following, respecting and affirming each other's gifts and expertise in the journey to a fully deracial home. It means having both the humility to lead and the courage to follow25 based on negotiation among participants in a particular situation.

2.4.3 Self-love and friendship

This metamorphosis (Mamdani), repair (van Wyngaard) or overturning (Jennings) towards true humanity is a call for a liberating new birth, a conversion to radical neighbourly love in its four dimensions, as set out above. However, one more dimension of love needs to be added, namely the call to love and affirm ourselves as image bearers of the living God. This is such a basic dimension of love that it shapes all four other dimensions, whether we are working separately as small "usses" or jointly as an inclusive "US." The Jewish proverb of roots and wings is helpful here: To love ourselves is to be deeply rooted in who we are - in our family, language, culture, confession, etc. - so that we are able to develop strong wings - enabling us to meet and engage confidently and sensitively with people who are very different from us. By learning to hold together, paradoxically, our distinctively separate roots and encountering convergent wings, we could grow together into maturity, building a home together.

Sabelo Ntwasa, one of the early pioneers of Black Theology in South Africa, wrote in 1971 about the need for friendship between black and white people:

Not a friendship in which the one is expected to 'toe the line' of the other. It means a free give-and-take in which both are open to being changed by the encounter. If there is this living alongside of and undergirding the situationally separated organizations for working out strategy, then there is hope for a future non-racial society not based on either White or Black values, but on human values (Ntwasa, 1971:22f).

This quote shows that the logic of an iterative "scissors" journey was present in South African Black Theology from the beginning as an integral part of the quest for true and shared humanity. In this regard, Biko (1978:26), in addition to his critique of white liberals, also accorded them an important, albeit uncomfortable, role:

The liberal must serve as a lubricating material so that as we change the gears in trying to find a better direction for South Africa, there should be no grinding noises of metal against metal but a free and easy flowing movement which will be characteristic of a well-looked-after vehicle.

This is the kind of role that a committed group of theologians, black and white, could play in the larger society to help overcome the tensions across the various fault lines.

2.4.4 The dynamics of covenanting encounters

How could such an iterative covenanting journey be organised and structured? For really transformative encounters to occur, I believe that small groups of black and white theologians should commit themselves to meeting for a set number of sessions, jointly-separately-jointly, following the iterative "scissors" strategy explained above. For example, an academic department or a theological society (like SAMS) could devote a week-long writing retreat or a series of weekly engagements to such an in-depth covenanting journey.

The theme for such a time-bound joint project could start from any dimension of the praxis matrix. It could be an urgent issue of contextual understanding, like unemployment or Operation Dudula; it could be an exercise in ecclesial scrutinies, like liturgy or church governance; it could be an issue of spirituality, like intercession or fasting; it could be a biblical topic like the Lord's Prayer or the Beatitudes; it could be a strategic issue requiring joint action; it could be an exercise in reflexivity in which participants share the stories of their personal journeys and the conversions they have experienced. From whatever dimension of the matrix the topic is drawn, all the dimensions must be involved in the encounters.

The outcome may not be many academic articles, as in a usual writing retreat or academic publication project. The emphasis is on the process of deracialising our identities and relationships more than on the product. However, such a series of encounters could also lead to publications. It could produce a deracial covenanting manual for community groups or a set of conversational YouTube videos about it. It could lead to ongoing joint projects, such as writing a press statement on a current challenge in society, a deracialising Sunday school curriculum, a set of liturgical suggestions to commemorate neglected historical events (like the emancipation of slaves in South Africa), a new decolonial church history, a commentary on a Bible book, a series of sermon outlines, guidelines for a ministry project to homeless people, to mention some examples.

We often lament the prophetic silence of "the church." Why do we not break that silence by communicating transformatively to (and within) our communities on the basis of consensus views that we develop together? I am not suggesting that such engagement replace traditional writing retreats or academic conferences. Such activities are essential to building our individual CVs. However, if we want to covenant together to build a just and liberated home, and are willing to undergo the metamorphosis suggested by Mamdani, then the format of our gatherings should also embody such transformative encounters.

The dynamics of this covenanting process cannot be limited to organised gatherings. This transformative journey can become a way of life by reading one another's publications, reflecting on the ideas expressed in them, and engaging in regular personal conversations. Perhaps that is the most important outcome to work for.

2.4.5 Facilitation

The facilitation of these encounters, in the parallel BTL and WTL groups and the joint gatherings, is of critical importance for the fruitfulness of the process. The encounters should be planned by a joint steering committee of black and white colleagues so that all the arrangements are decided together. The shared gatherings should ideally be jointly chaired by a black and a white colleague, who also chair the respective parallel sessions. Since the encounters could evoke strong emotions, the facilitation should proceed along "ground rules" that are negotiated beforehand and agreed on by the participants. The expression of emotions should be expected and welcomed, but also guided into constructive channels by implementing the agreed-upon ground rules.

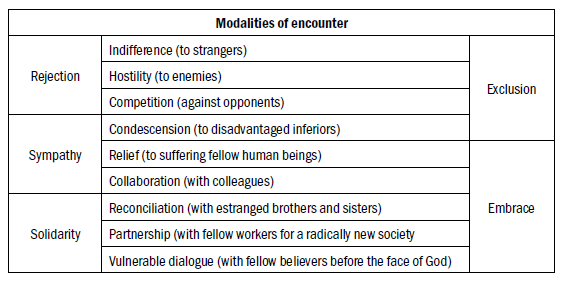

The following diagram, adapted from another publication (Kritzinger, 2022), maps the kinds of interaction that typically occur across fault lines in society. A covenanting journey aims to promote the types of interaction towards the bottom of the diagram.

2.4.6 Community focus

The intention of my proposal for a covenanting journey among theologians is not to create an elitist exercise, but that is a real temptation. Therefore, we need to build safeguards to prevent it.

A theological-spiritual safeguard would be to stress that our encounters occur in God's presence, before God's face, as part of God's mission, and that the incarnation affirms that God unashamedly assumed our human nature in Jesus of Nazareth, God with us, so that God does not encounter us "from above" but "from the side," standing with the victims/survivors of injustice, as Article 4 of the Belhar Confession articulates it:

We believe that God has revealed Godself as the One who wishes to bring about justice and true peace among people; that in a world full of injustice and enmity God is in a special way the God of the destitute, the poor and the wronged and that God calls the church to follow in this; ... that the church, belonging to God, should stand where God stands, namely against injustice and with the wronged; that in following Christ the Church must witness against all the powerful and privileged who selfishly seek their own interests and thus control and harm others (Belhar Confession, 1986).

God's praxis of solidarity is not with "humankind" (abstractly and universally conceived), but particularly with those at the "underside of history." It is from there and through them that God in Christ encounters the whole of humanity, calling everyone to account for what they are doing to "the least" of Christ's sisters and brothers. The call to discipleship - to take up our cross, to sell everything and give it to the poor, to "come and die" (Bonhoeffer, 1959:79) - means (among many other things) that we are sent and called to stand with God among, with and for the poor and oppressed. That is where God calls proponents of LWT and BTL to meet one another: At the foot of the cross, by meeting the crucified Christ among the cross-bearers (Mofokeng, 1983) and encountering the Spirit among black architects of life, "Umoya is the creative participation of black people with dignity as architects of life with God the Architect of life" (Vellem, 2017:9).

In addition to this theological safeguard, we also need to build procedural safeguards in terms of agency by listening to poor, unemployed and excluded people, including them as interlocutors in our conversations. Another safeguard against elitism would be deciding on a specific communication strategy for the black and white communities. It must be clear that our covenanting journey is not aimed at creating a perfect "liberated zone" to show up how "backward" everyone else is, but instead to become a non-arrogant "salt of the earth" catalyst that could spread "true humanity" to others - to the extent that we are beginning to discover it together with sincerity, in Christ, from God and before God. Willie James Jennings (2020:13) calls theologians (and theological education) out of elitist spaces towards "the crowd:"

The crowd was not his [Jesus'] disciples, but it was the condition for discipleship. It is the ground to which all discipleship will return, always aiming at the crowd that is the gathering of hurting and hungry people who need God.. Theological education must be formed to glory in the crowd, think the crowd, be the crowd, and then move as a crowd into discipleship that is a formation of erotic souls, always enabling and facilitating the gathering, the longing, the reaching and the touching. being cultivated in an art that joins to the bone and that announces contrast life aimed at communion.

On this point of community focus, the question arises about the relative representation of black and white participants in such a covenanting journey. At first glance, one would think that there should be equal representation of black and white participants, but it may be better to replicate the country's demographic composition in the process.26 Since whiteness is about power and control, a liberating whiteness is more likely to arise when we, as white theologians, are outside white cocoons and gated communities, learning to do theology as a minority in the larger (Southern) African context. The only proviso is that the number of white participants should be large enough to ensure a fruitful discussion among themselves.

2.5 Contextual understanding

The contextual understanding dimension of the matrix invites and challenges all of us to rethink our views of the racialised nature of South African society and to listen to the views of others.

2.5.1 Reconstructing history

The challenge of reconstructing the history of South Africa and the role of churches in that history is a major task of this covenanting journey. In his study on Black Theology, The way of the black Messiah, Witvliet (1987:182) contended that "the struggle for the past is an essential part of the struggle for the future," but then cautioned:

Liberation is not served with absolutized half historical truths on either side or the other . The texture of historical fabrications is only broken apart when the realization dawns that coping with a past which is hard to get at and even harder to accept is a task to be shared between whites and blacks.

Smit (1990:15), commenting on H. Richard Niebuhr, argued in a similar vein:

A common memory is necessary for real community ... The important point is that this whole process of interpretation, remembering and appropriating is for Christians 'a moral event,' 'a conversion of the memory.' Remembering the suffering of the past, both caused and suffered by one's own group, and appropriating the suffering of others is the only way to real solidarity, and the only proper response to the revelation of the one, living God in Christ.27

In this reconstruction of the past, it is not necessary to arrive at total consensus; what is important is that we listen to one another's stories, explore the archive together and craft a fragile shared vision for the future. It is important, though, to heed the caution contained in the view of Judith Gruber (2020), who develops a "spectral" theology of mission by reading history as "ghost stories." Based on the insights of postcolonial authors like Gayatri Spivak (1999) and Achille Mbembe (2017), she suggests replacing a teleological "historiography of the cure," which constructs a triumphant, linear narrative from wounding to healing, with a spectral (haunting) historiography as a lens for conceptualising history, memory, trauma and justice (Gruber, 2020:382). It means seeing decolonisation not as healing but as survival, taking place in a deeply wounded and "irreducibly polyvalent and ambiguous world" (Gruber, 2020:389). Spectral missiology is practised as missio ad vulnera (mission to wounds) and does not speak from a position of epistemic privilege, confidently proclaiming salvation as linear progress, but instead:

Proceeds by ways of re/membering that discern and compose signs of redemption from the ghostly work for life in the midst of death... [it] does not ground hope for redemption in retrotopian or utopian warrants, but traces its rising from the midst of the messiness of violent histories, marked by the forces of empire (Gruber, 2020:392).

This alerts us not to underestimate the deep woundedness inflicted on (South) Africa by colonisation, but to engage in "a hermeneutics of wounds and tears that performs transformation by rupturing established imaginations of post/colonial history" (Gruber, 2020:385).

2.5.2 Fault lines

It is not the purpose of this paper to give a detailed contextual analysis of South Africa, but throughout, I have been working with the notion of the major "fault lines" that divide us. In the iterative covenanting journey outlined above, a key challenge will be to appreciate how other participants understand South African society and the factors that shaped it. At this point, deep differences often emerge between black and white theologians, but also within both groups. Here, too, the aim is not to arrive at a complete consensus but to grow in understanding that enables the building of a home open enough to accommodate differences.

Since the World Bank recently confirmed that South Africa is the most unequal society in the world, the economic fault line will be one of the most important to address, as white and black theologians covenant together for an oikos economy, for a household of freedom where no one goes hungry.

2.6 Ecclesial scrutiny

This dimension emphasises the need to analyse the praxes of churches adequately. Often the dimension of "context analysis" in a praxis cycle does not include this element, but a process of covenanting together for a deracialised society cannot evade examining the state of churches and their role in creating, entrenching or overcoming the existing fault lines. Vuyani Vellem (2015:5) judged South African churches to be bound by five shackles: colonial legacy, pigmentocratic structures, cultural domination, complacency with capitalist exploitation and false consciousness. These shackles are similar to the fault lines I have identified, and his call to "unshackle" the church from these is another way to describe a covenanting journey for metamorphosis.

Participants in a covenanting journey could use various frameworks as "lenses" to analyse church praxis to explore the functioning ecclesiologies (or "ecclesial imaginaries") that shape church life.28 Such analyses are necessary if this journey is to produce impactful strategies to promote change in churches. One way theological educators can contribute to this is to design curricula that produce new generations of church leaders who can initiate transformative covenanting journeys in congregations.

3. Conclusion

As I said in the beginning, this paper focuses on the fault line of race, but an approach of covenanting together for change could be used similarly to address the other fault lines. It would involve similar iterative journeys of committed participants:

Covenanting together for gender justice, dignity and safety

Covenanting together for economic justice, empowerment and employment

Covenanting together for African justice and philoxenia

Covenanting together for linguistic/cultural justice and celebration

Covenanting together for theological justice and enrichment

There is a large amount of intersection between the six fault lines: these five and the deracialising journey I have proposed. It is artificial and fruitless to separate them, but it may help to distinguish them in order to examine what each contributes to our overall malaise. First, however, we must heed the words of Kimberlé Crenshaw, the African American law professor who coined the term intersectionality in 1989:

Because the intersectional experience is greater than the sum of racism and sexism, any analysis that does not take intersectionality into account cannot sufficiently address the particular manner in which Black women are subordinated (Crenshaw, 1989:140).

In a more recent interview, she elaborated:

It [intersectionality] is basically a lens, a prism, for seeing the way in which various forms of inequality often operate together and exacerbate each other. We tend to talk about race inequality as separate from inequality based on gender, class, sexuality or immigrant status. What's often missing is how some people are subject to all of these, and the experience is not just the sum of its parts (Steinmetz, 2020).

In other words, we cannot simply add insights after exploring these different fault lines separately. Intersectionality highlights the cumulative effect at work between various forms of inequality and exclusion. For example, a poor black lesbian Shona-speaking Zimbabwean woman living in South Africa is exposed to quantitatively more challenges than others and a qualitatively different, compounded set of challenges. As we enter more deeply into journeys of covenanting together to overcome the fault lines, we will need to find the wisdom to hold these intersecting dimensions together and to do justice to the least (and most burdened) of the sisters and brothers of the Lord Jesus Christ.

Can we build a home together? The challenges are daunting, but I believe we can - and I have suggested one way we, as theologians, could start doing it.

References

Arndt, W.F. & Gingrich, F. W. 1957. A Greek-English lexicon of the New Testament and other early Christian literature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Baron, E. & Maponya, M.S. 2020. The recovery of the prophetic voice of the church: The adoption of a 'missional church' imagination. Verbum et Ecclesia, 41(1), a2077. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v41i1.2077 [ Links ]

Belhar Confession. 1986. Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa. [ Links ]

Bevans, S.B. 2002. Models of contextual theology. Revised and expanded edition. Maryknoll: Orbis. [ Links ]

Biko, S.B. 1978. I write what I like. London: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Bonhoeffer, D. 1959. The cost of discipleship. London: SCM Press. [ Links ]

Bosch, D.J. 1979. A spirituality of the road. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press. [ Links ]

Bosch, D.J. 1991. Transforming mission: Paradigm shifts in theology of mission. Maryknoll: Orbis. [ Links ]

Buffel, O. 2015. Bringing the crucified down from the cross. Preferential option for the poor in the South African context of poverty. Missionalia, 43(3), 349-364. http://dx.doi.org/10.7832/43-3-123 [ Links ]

Cabral, A. 1973. Return to the source: Selected speeches of Amilcar Cabral. New York & London: Monthly Review Press. [ Links ]

Chopp, R. 1998. A rhetorical paradigm for pedagogy. In F.F. Segovia & M.A Tolbert (eds.). Teaching the Bible: The discourses andpolitics of biblical pedagogy (pp. 299-309). Maryknoll: Orbis. [ Links ]

Crenshaw, K. 1989. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1(8), 139-167. Available from: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8. [ Links ]

Dunn, J.D.G. 1998. The theology of Paul the apostle. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Erlander, D. 1992. Manna and mercy: A brief history of God's unfolding promise to mend the entire universe. Mercer Island, Washington: The Order of Saints Martin and Teresa. [ Links ]

Fox, M. 1999. A spirituality named compassion: Uniting mystical awareness with social justice. Rocherster, VT: Inner Traditions. [ Links ]

Gordon, L.R. 2015. What Fanon said: A philosophical introduction to his life and thought. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

Jennings, T.W. Jr. 2013. Outlaw justice. The messianic politics of Paul. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

Jennings, W.J. 2020. After whiteness: An education in belonging. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Kearney, R. 2015. Toward an open Eucharist. In M. Moyaert & J. Geldhof (eds.). Ritual participation and interreligious dialogue: Boundaries, transgressions and innovations (pp. 138-155). London: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, J.N.J. 1988. Black Theology - Challenge to mission. DTh thesis, University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, J.N.J. 1991. Re-evangelising the white church. Journal of Theology for Southern Africa, 76(9), 106-116. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, J.N.J. 1997. Interreligious dialogue: problems and perspectives. A Christian theological approach. Scriptura, 60, 47-62. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, J.N.J. 2001. Becoming aware of racism in the church. The story of a personal journey. In M.T. Speckman & L.T. Kaufmann (eds.). An agenda for contextual theology: Essays in honour of AlbertNolan (pp. 231-275). Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, J.N.J. 2008. Liberating whiteness: Engaging the anti-racist dialectic of Steve Biko. In C.W. du Toit (ed.). The legacy of Stephen Bantu Biko: Theological challenges (pp. 89-113). Pretoria: Unisa, RITR. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, J.N.J. & Saayman, W. 2011. David]. Bosch: Prophetic integrity, cruciformpraxis. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, J.N.J. 2013. The role of the Dutch Reformed Mission Church and the Dutch Reformed Church in Africa in the struggle for justice in South Africa, 1986-1990. Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae, 39(2), 197-221. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, J.N.J. 2022. White responses to Black Theology: Revisiting a typology. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 78(3), a6945. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v78i3.6945 [ Links ]

Liddel. & Scott. 1900. An intermediate Greek-English lexicon. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [ Links ]

Mamdani, M. 1998. When does a settler become a native? Reflections of the colonial roots of citizenship in equatorial and South Africa. Inaugural lecture as A.C. Jordan Professor of African Studies, University of Cape Town, 13 May 1998. Available from: https://citizenshiprightsafrica.org/when-does-a-settler-become-a-native-reflections-of-the-colonial-roots-of-citizenship-in-equatorial-and-south-africa/ (Accessed 3 March 2021). [ Links ]

Mamdani, M. 2021. Neither settler nor native. The making and unmaking of permanent minorities. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

Mangayi, L. 2016. Mission in an African city. Discovering the township church as an asset towards local economic development in Tshwane. DTh thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Marx, K. & Engels, F. 1968. Selected works in one volume. Moscow: Progress Publishers. London: Lawrence & Wishart. [ Links ]

Mbembe, A. 2017. Critique of black reason. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

Mofokeng, Takatso A. 1983. The crucified among the cross-bearers. Kampen: Kok. [ Links ]

Ntwasa, S. 1971. Inter-racial contact and polarization. UCM Newsletter, Second semester, 21-23. [ Links ]

Pilario, D.F. 2005. Back to the rough grounds of praxis: Exploring theological method with Pierre Bourdieu. Leuven: Leuven University Press. [ Links ]

Russell, L.M. 1987. Household of freedom: Authority in feminist theology. Philadelphia: Westminster Press. [ Links ]

Russell, L.M. 1993. Church in the round: Feminist interpretation of the church. Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Sacks, J. 2007. The home we build together: Recreating society. London: Continuum. [ Links ]

Smit, D.J. 1990. Theology and the transformation of culture. Niebuhr revisited. Journal of Theology for Southern Africa, 72, 14-20. [ Links ]

Spivak, G. 1999. A critique of postcolonial reason: Toward a history of the vanishing present (4th ed.). Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Steinmetz, K. 2020. She coined the term 'Intersectionality' over 30 years ago. Here's what it means to her today. Interview with Kimberlé Crenshaw. Available from: https://time.com/5786710/kimberle-crenshaw-intersectionality/?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=the-brief&utm_content=20200226&xid=newsletter-brief. [ Links ]

Van Wyngaard, G.J. 2019. In search of repair: Critical white responses to whiteness as a theological problem - A South African contribution. PhD thesis, Vrije Universiteit van Amsterdam. [ Links ]

Vellem, V.S. 2002. The quest for Ikhaya: The use of the African concept of home in public life. Master of Social Science dissertation, University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Vellem, V.S. 2017. Un-thinking the West: The spirit of doing Black Theology of Liberation in decolonial times. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies, 73(3), a4737. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i3.4737 [ Links ]

West, C. 2018. Twitter, Oct 17. Available from: https://twitter.com/cornelwest/status/1052585306916974592. [ Links ]

Witvliet, T. 1987. The way of the black Messiah: The hermeneutical challenge of Black Theology as a theology of liberation. London: SCM Press. [ Links ]

Young, J.O. & Brunk, C.G. 2012. The ethics of cultural appropriation. Chichester: Wiley- Blackwell. [ Links ]

1 Prof Kritzinger is an Emeritus Professor at the University of South Africa (UNISA), and is currently a Ressearch Fellow at UNISA. He can be contacted at kritzjnj@icon.co.za.

2 These are drawn from the call for papers sent out by the SAMS administration on 31 January 2022.

3 Professor Vuyani Vellem (1968-2019) taught Systematic Theology at the University of Pretoria. He was a leading South African proponent of Black Liberation Theology.

4 The word ikassie emerged from the architecture of apartheid cities and towns, where white people lived in the centre and the surrounding suburbs, while black people were restricted (and removed) to "locations" (later called "townships") on the periphery, beyond the factories and municipal dumping grounds. It was the Afrikaans word lokasie that gave birth to the term ikassie in township parlance.

5 Legae is the Sotho-Tswana equivalent of the Nguni term ikhaya, meaning "home."

6 Cultural appropriation occurs when someone appropriates ideas, concepts or symbols from another culture in a way that "causes unjustifiable harm or is a source of profound offense," by "striking at the core values and sense of self" of another person or culture (Young & Brunk, 2012:5).

7 Among many influential voices in this regard, that of Amilcar Cabral from Guinea-Bissau has remained influential. See his contributions on "National liberation and culture" and "Identity and dignity in the context of the national liberation struggle" (Cabral, 1973:39-74).

8 This proposal has also drawn on the use of 'oikos' by Mangayi (2016) in his oiko-missiology.

9 The term praxis has a long history in European philosophy, going back to Aristotle. Pilario (2005) gives a broad survey and an incisive critique of the use of the term in Aristotelian, Marxist and some contemporary social theories, particularly of Pierre Bourdieu.

10 Bevans (2002:79-87) uses the Canadian systematic theologian Douglas John Hall and a number of feminist theologians as examples to illustrate his "praxis model" of contextual theology.

11 I have borrowed this term from Vellem (2017). He adapted it from the view of Immanuel Wallerstein, who emphasised that an unthinking is required, which is more radical than a rethinking (Vellem, 2017:2).

12 Some elements of my position and story in relation to racism are reflected in publications like Kritzin-ger (2001; 2008; 2013; 2020).

13 Numerous biblical passages could be used at this point, but I decided to use one not usually quoted in the "biblical basis" for mission. However, in his study on mission spirituality, Bosch (1979:30) used it to identify the need for "Christian mission from the West to unlearn the triumphalism of the hawker."

14 The Greek verb kapêleuö, translated by the NRSV as "peddling" can mean being a retail dealer but often has the negative connotation of being a hawker or a huckster, trading unethically (Liddel & Scott, 1900:400). Arndt and Gingrich (1957:404) comment, "Because of the tricks of small tradesmen the word comes to mean almost adulterate" (italics in original). In Isaiah 1:22 (LXX) the traders (kapêloi) are judged for mixing wine with water.

15 The Greek expression ex eilikrineias that is used here has the connotation of unmixed, pure, without alloy (Liddel & Scott, 1900:228), in sincerity, from purity of motive (Arndt & Gingrich, 1957:221).

16 The Greek expressions "ek theou" (literally "from God") is translated by the NRSV as "sent by God" and "katenanti theou" (literally "before God") as "standing in God's presence."

17 Theodore Jennings uses "messiah Joshua" instead of "Jesus Christ" in his reading of Paul's letter to the Romans to uncover the apostle's "messianic politics."

18 Van Wyngaard (2019:150) explains that he drew his title from the Jewish theologian Peter Ochs.

19 In Manna and Mercy, Erlander (1992) contrasts oppressive triangles of power, as found in the hierarchical systems of the Pharaohs, king Solomon and the Roman Empire, with the liberating manna-and-mercy message of Scripture. His image influenced my distinction between triangle and dome as contrasting shapes of authority.

20 These two images were used very creatively by Letty Russell (1987; 1993) to express the nature of the church as a round table and the "kingdom of God" as a "household of freedom."

21 I used a similar (but threefold) framework before, with specific reference to interfaith relations (Kritzinger, 1997), but this framework can be applied to any significant relationship.

22 This expression is from the US black theologian, Kameron Carter, who spoke of "probing the Christian wound that has produced us all" (van Wyngaard, 2019:4).

23 This expression comes from Cobus van Wyngaard's thesis, In search of repair (van Wyngaard, 2019).

24 The South African white theologians who have taken a consciously liberational stance in dialogue with BTL sadly represent a small percentage in the large community of white theologians (see van Wyngaard 2019:183ff).

25 It may sound counterintuitive to associate humility with leading and courage with following, instead of the other way round, but for me it is an essential move in unthinking race, gender and power in theology.

26 I thank Bishop Sidwell Mokgothu and Dr Cobus van Wyngaard for suggesting this in separate conversations.

27 I used these two quotes of Witvliet and Smit in a paper on the re-evangelisation of the white church (Kritzinger, 1991:111), but I repeat them here since they are vital to historical reconstruction in this covenanting journey.

28 An example of this kind of ecclesial scrutiny, in addition to Vellem (2015), is Baron and Maponya (2020).