Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Missionalia

versão On-line ISSN 2312-878X

versão impressa ISSN 0256-9507

Missionalia (Online) vol.48 no.3 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.7832/48-3-374

ARTICLES

Equipping Lay Leaders for Christian Ministry in the Anglican Church of Kenya through Theological Education by Extension. Prospects and Challenges

George Kiarie; Mary Mwangi1

ABSTRACT

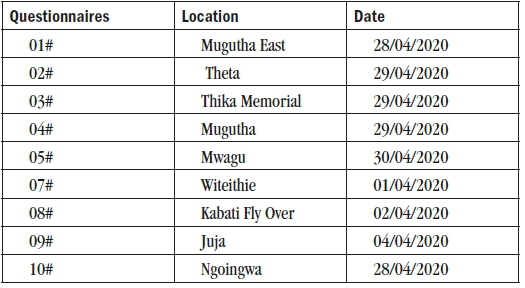

The mission of ecclesia is to empower and equip its leaders for Christian ministry. This has been possible through theological education, particularly for the ordained ministry. Though laity form a substantial number in the Anglican Church of Kenya (ACK) ecclesiastical context, they are theologically ill-equipped for Christian ministry despite their integral roles in pastoral and administrative functions in their respective local congregations. The article was informed by both empirical and non-empirical data drawn from the ACK diocese of Thika in 2020. The data was derived from 11 questionnaires where two former diocesan Theological Education by Extension (TEE) co-ordinators and nine Archdeaconry TEE facilitators in the diocese of Thika were engaged. Archival documents from the diocese and review of literature also enriched the study. The study's findings show that the success of the 21st century ecclesia solely depends on how thoroughly the lay leaders are empowered and equipped theologically through TEE.

Key words: Anglican Church of Kenya, Theological Education by Extension, Lay leaders, Ministry

1. Introduction

The ACK is one of the missions-based Churches in Kenya. Lately, the Church has recorded significant growth numerically, where its adherents are to the tune of over 5.86 million (Anglican Church of Kenya, 2019: ii). Though these figures are appealing to missiolo-gists, there is a glaring problem; Dickson Nkonge cites that the gap between clergy who are ordained in relation to the lay Christians is so wide that one wonders how the Church is empowering and equipping its people for Christian ministry (2011:154). These statistics speak volumes in terms of how the ACK is equipping its leaders for Christian ministry; it is important to understand whether there is any fundamental role that lay Christians play in the life of the Church. The ACK has three houses that work harmoniously and complement each other, namely the 'house of bishops', 'house of clergy', and 'house of laity'. Constitutionally, all the houses are equal, though practically the house of bishops take the centre stage and dominates the other two houses.

In a real sense, the house of laity is perceived as inferior, despite its integral role in the advancement of Christian faith in the ACK. This perception has prevailed in the way the ACK equips its three houses, where the first two houses receive sound theological formation and the house of laity receives minimal, if any, theological training. With this knowledge, the ordained ministers acquire administrative and pastoral skills for Christian ministry. However, the house of laity has been neglected in the ACK despite the pew being the majority vis-a-vis the altar. This means that it is not business as usual in the ACK since the big gap between the two houses of the ordained and laity need to be bridged. Thus, TEE becomes a powerful way forward to put an end to this situation. The section below explains how TEE emerged in the ecclesiastical settings.

2. Emergence of TEE in Latin America

TEE is a form of alternative theological education in the ecclesiastical context. As a form of education system, Sam Burton defines it as, "a method of education which doesn't disrupt the learner's productive relation to society" (2000:28). This means that it is a form of open education where the learners can pursue their studies at their pace while they engage in their normal chores of life. This form of theological education originated from Latin America where the Presbyterian Church devised a local approach to its dire need for trained Church leaders. This local initiative was championed by Ralph Winter, Ross Kinsler and James Emery who were missionaries there. Historically, "the TEE began in 1963 as an innovative training program for 'extending' theological education from a central seminary where the untrained Church leaders were" (Burton, 2000:27).

As it is evident that the centre of Christianity has shifted from the global North to global South, this phenomenon has seen the Churches registering significant growth of Christians numerically. This growth of Christians is not commensurate to the number of clergy already trained to minister to the ever-increasing number of Christians. To this end, these pioneers of the TEE in Guatemala made up their mind to launch this programme. They were motivated by various reasons, as Kangwa Mabuluki outlines:

Among the challenges that Presbyterian Church in Guatemala was facing was the inability of its seminary - Seminario Evangelico Presbiterlono de Guatemala - to train enough ministers to cope with the ministerial needs of a rapidly growing Church. The Church did not have the resources to increase the capacity of the seminary. Most Church leaders who were serving in the rural congregations had no training yet could not leave their families to go to the residential college. Even if they were able to leave their families, the college could only train a few people at a very high cost. Further, pastors trained in the seminary developed expectations of a "professional" salary, though ... majority of the Churches were too poor to meet those expectations. As a result, even those limited number trained could not be employed by the Church (2013:832).

Considering the above, it can be deduced that the emergence of TEE in the global South, particularly in Latin America, was a response to a local ecclesiastical threat to its mission. As Mabuluki avers, this became an alternative form of equipping Church leaders in Guatemala. The beauty about this mode of theological education is that it deconstructed the conventional perception that theological education is the realm of the ordained group. Thus, it declericalised theological education and opened the door wide for equipping lay leaders in the Church who had been sidelined for long. Reacting to this paradigm shift in Christian mission, W.P. Wahl saw this as beneficial to the whole household of God, because accessibility of theological education through this form of education broke all chains and lifted all, "geographical access, economic access, cultural access, ecclesiastical access, gender access, race access, class access, different abilities access, and pedagogical access" (2013:271). What this ultimately meant was that theological liberation was declared and all the members in God's oikos are at liberty to enrol for theological education at any time and place. The space is now the limit for all prospective candidates for theological education.

While this form of education began in Latin America among Presbyterians, this model was appraised in other parts of the world. Africa became one of those destinations where this form of education system in ecclesiastical set up was desired to curb the acute shortage of ordained ministers of the word of God. This is because at the global level it is estimated that there are 2 million Churches all over the world without pastors; however, at the continental level this number is a glaring problem. To exacerbate this, even with the few pastors the continent has, it is unfortunate that more than 80% of African pastors are insufficiently trained (Houston, 2009). To bridge the gap and drastically improve the level of theological education of the African pastors, TEE offers the better option. To this end, this article shifts its attention to Africa; however, it is narrowed down to Kenya in the ACK because of its intensity.

3. TEE in the Anglican Church of Kenya

Research reveals that by 1977 Africa already had 57 TEE programmes with a total number of 6869 students (Kinsler, 1981:172). These figures suggest that TEE was already in operation on the African continent immediately after initiation of this alternative mode of theological education in Latin America. Worth noting is that these two contexts, despite being in two separate continents, share a lot in common, by virtue of them being in the global South where the number of Christians is growing tremendously. In highlighting the works and origins of TEE in the ACK, Anglican scholars are divided on the specific dates when TEE was introduced, as one suggests 1974 and another 1975 (see Nkonge, 2016; Oriendo, 2010 respectively). While Nkonge elaborates his dates, Simon Oriendo only gives the dates and leaves it there. This paves the way to conclude that TEE was introduced in 1974 in ACK. Like TEE in Guatemala in Latin America where the programme was championed by missionaries, so too the TEE in Kenya was introduced by the CMS missionaries to Kenya. Nkonge rightly states, "Canon Keith Anderson is the pioneer of TEE in the ACK. From 1974 he was involved in the establishment of TEE programmes at certificate level in Kenya" (2016:120). The programme started in the hands of the missionaries with resources from their sending missions in the West. This jeopardized Henry Venn's vision of Three-Self or Four-Self. All in all, the ministry of TEE did put foot on Kenyan soil and this was motivated by the rate of growth of Christianity in ACK because the ACK was now conquering new territories in Kenya where it had not been opened. As with other Churches in global South, ACK fell into a leadership crisis because it could not meet the demand of its flock. Hence, according to Oriendo, the ACK established the TEE with two main objectives as captured here that: the ACK established the TEE programme ... to address the problem of lack of enough trained clergy for the pastoral ministry. The ACK sought to train the lay leaders who were able to some extent, offer spiritual oversight in the Churches, in the absence of a clergy (2010:77).

Although TEE was introduced in ACK by 1974, its presence was not felt in the province and its dioceses until one year was over. Information regarding its work in the ACK between 1974 and 1975 is scanty to establish what was really going on. Fortunately, in 1975 there was a paradigm shift in TEE landscape in the province as the diocese of Nakuru became the first diocese in the province to roll out TEE ministry in the parishes. Nkonge articulates how it was endorsed by its diocesan bishop, "in the ACK, TEE was first started in the diocese of Nakuru in 1975 by bishop Neville Langford Smith who was the first bishop of Nakuru diocese which was formed in 1961" (2016:120). In this line of thought, it is evident that the diocesan bishop of Nakuru had at heart the importance of TEE in his jurisdiction. This good will from the diocesan leadership enabled the programme to flourish so well that most parishes in Nakuru had TEE classes. However, due to the high number of congregations arising in the diocese, it could not meet the demand for ordained priests and hence those lay leaders who enrolled for TEE were considered for ordination.2

The diocese of Nakuru became a pilot project in the province and did so well that the fire of TEE was lit in other dioceses. The chain of its spread is well put that, "by 1982 four dioceses of the ACK were running TEE programmes in both certificate and parish level. These were the dioceses of Mount Kenya East, Maseno South, Nakuru, and Nairobi. In 1985, TEE had become stronger in the ACK having been started in seven out of the ten dioceses3 in Kenya" (Nkonge, 2016:120). This shows a Church willing to educate her adherents lest they perish for lack of theological knowledge to pastor and administer the work of God in their respective congregations. By and large, the great work of the TEE in the province became overwhelming. Furthermore, there was no proper co-ordination at the provincial level because every diocesan TEE programme was autonomous. This saw the TEE programmes dwindling in various dioceses, and eventually the programme that educated ACK adherents was on the verge of collapsing. Luckily, this concern got the attention of the province, which resolved to revive TEE in all the ACK dioceses. No doubt the province took the matters seriously, as demonstrated by enthusiasm and radical measures of the ad hoc committee mandated to ensure the programme was on its feet again. As such, Nkonge opines:

On 11th June 1986, the Provincial Board of Theological Education (PBTE) under the chair of bishop David Gitari ... resolved that all Anglican licensed lay leaders [sic] and evangelists serving in parishes within the province had to undergo some theological training through TEE ... [while] on 24th May 1996 the PBTE resolved for the first time to hire a full-time Provincial TEE co-ordinator and establish and equip a Provincial TEE office ... that would manage TEE in the entire ACK and assist dioceses that did not have TEE programmes to commence them (2016:120).

With this wake-up call in late 1990s, ACK saw a new dawn where TEE classes commenced in different dioceses with the goal of training the existing and new lay readers and evangelists in the ministry. The beauty with this form of education was that theology was now being done from below and the group that did not have an opportunity to enrol in a residential theological seminary could now do so within their reach and without much hassle of leaving their families behind or financial strain. Thus, the good news of TEE flowed to the dioceses and now the provincial co-ordinator could follow up the new groups in different dioceses as he/she ensured the existing ones maintained the momentum.

4. TEE in the ACK Diocese of Thika

The ACK diocese of Thika is one of the dioceses in the province where the TEE good tidings were handed down immediately after its formation. The diocese was carved in July 1998 from dioceses of Mount Kenya South and Mount Kenya Central, with its first bishop being Rt Rev Dr Gideon Githiga. At the onset, the diocese had 23 parishes, 26 clergy, and 9,488 Christians. In this formative stage, the diocese came up with different departments and TEE was one of them when in July 1999 it was inaugurated. The diocese saw parishes opening doors to the TEE programme, such that 12 active TEE groups registered for the work of empowering and equipping the laity for Christian ministry. In the same year of 1999, Bishop Githiga appointed Rev Joyce Kabuba (today the Archdeacon of Gatundu Archdeaconry) as the first Diocesan TEE co-ordinator. She was mandated to champion the work of TEE in the diocese and to liaise with the Provincial TEE Co-ordinator for the smooth running of the programme. At diocesan level, the TEE co-ordinator worked with TEE group facilitators who acted as group moderators in various parishes, since there were no archdeaconry TEE co-ordinators.

Over time the TEE groups kept fluctuating and some collapsed, thus the department was not stable. Diocesan archival documents indicate a total of 23 active TEE groups between 1999 and 2003 and three CCRS classes. Between 2004 and 2009 there were 304 active TEE groups with an estimated 300 TEE learners in the diocese. From 2013 to 2015 the department experienced a severe leadership crisis. This was escalated by the lack of a full-time diocesan co-ordinator. The ripple effect was the crumbling of the TEE department in the diocese. Luckily, there were two active TEE groups that were struggling to survive in Juja and Kabati Fly parishes. At the beginning of 2016, the number had not changed, and the entire diocese had only two active TEE groups in operation. In 2017 the number grew, and the diocese had 18 active TEE groups5 while in 2018, 29 active TEE groups were functioning in different parishes.6 However, in 2019 and 2020, they registered dwindling numbers of active TEE groups that stand at 25 and 20 respectively. The Venerable Patrick Mukuna is the current diocesan TEE co-ordinator, assisted by archdeaconries co-ordinators.

5. What Motivated ACK Diocese of Thika Lay Leaders to do TEE?

The TEE programme in the ACK was tailored towards equipping lay leaders for Christian ministry. However, in the spirit of the priesthood of all believers, the scope was widened to embrace even Christians who were interested in this programme. To this end, many Christians enrolled for TEE classes for various reasons as the artide will articulate. The nature and mode of education in this programme becomes one striking motivation for the ACK Diocese of Thika Christians to join TEE classes. This motivation is captured well in the thoughts of Respondent #04 who rightly admits that she joined TEE classes because, "it is a training in which you study where you are" (Respondent #04). This means the flexibility of this programme is appreciated by most Christians in the diocese of Thika, especially those in formal professions as their availability is a challenge. With this mode of learning, TEE becomes an open learning to lay Christians who are equipped for Christian ministry where they are. As a result of its openness, this form of education is accessible to everyone as the programme reaches out to Christians where they are, unlike conventional theological training where the students must leave their comfort zone and move to where the seminary is. This form of learning helps justify that TEE is indeed an extension education. As Greg Parson states, "it is that method which reaches the student in his own environment rather than pulling him out into a special controlled environment".

Consequently, some lay leaders join theological seminaries directly from their local congregations without the slightest idea of what they expect there. Such candidates have no exposure to any theological education in their life, but they get an opportunity to join full-time theological studies in seminaries. Whether there is any advantage of prior knowledge or not, some diocesan Christians believed that those with TEE backgrounds were better off. This line of thought convinced some of them that their sole reason for joining TEE programmes in their respective local Churches was to prepare them for formal theological training in future. Toward this end, some joined TEE programmes in their local congregations because, "it is a training that will prepare me to study theology as a course" (Respondent #04). From this response, it can be said that some lay Christians in the diocese of Thika are enrolling in this form of theological education because it is viewed as a precursor to formal theological education. Although this is not a stepping stone to formal theological training, it becomes essential to those aspiring to join full-time theological studies as it gives them a glimpse of what lies ahead. Furthermore, they have an opportunity to compare the two modes of training and to synthesise them.

The study of TEE is truly enriching to the students as it invites them to deeply learn the word of God together. This has become a cornerstone to most Christians who are thirsty for the word of God. Out of this urge to study, TEE becomes an effective method of Christian discipleship. One respondent holds this motivational factor so dearly that when responding to the question about why he joined TEE, he wrote that this was as a result of, "the desire to study the word of God from a guided point of view... to fellowship in studying the word of God... [and] desire to grow in the word of God" (Respondent #09). This suggests that most lay leaders are in TEE groups because of their spiritual nourishment and Christian growth. Their thirst for the word of God is quenched in TEE as they are exposed to various TEE materials or books with different themes for Christian growth. Books such as Following Jesus increase their resolve to follow Christ; Old Testament part 1 and 2 helps them to understand the content and theology of the OT books in the two parts. As such, the study of TEE not only equips them academically, but as Oriendo states, "TEE helps students to grow spiritually" (2010:37).

Peer pressure is another motivation that has led many to join TEE classes in most parishes in the diocese of Thika. This was captured from a respondent who maintained, "I was challenged by my fellow Christians who had undertaken some TEE course books on the manner they articulated the word of God" (Respondent #08). Therefore, the way other Churches in the global South were highly influenced by Latin America response to their need of theologically informed lay Church leaders so do the laity in the diocese. They felt challenged by those who enrolled in this programme; it can be said that they became good mentors of their fellow Christians. When the Church members influence each other to join hands together in learning the word of God, not only are the local Church Christians edified by the word of God, but its members are all equipped for different ministries. Such a congregation has more informed and theologically sound lay Church members ready to take the good news of Christ to the entire world.

6. How TEE is Equipping the ACK Diocese of Thika Laity for Christian Ministry

John de Gruchy's writing in 2011 cites one of the setbacks in African Christianity as that lay people are theologically illiterate.7 He shifts the blame to theological educators and pastors in African Churches. However, with the introduction of the TEE programmes in the ecclesiastical settings and particularly in the ACK Diocese of Thika, this challenge is being averted. With this programme in most local Churches, their leaders and Christians are now invited to think theologically, especially during their discussions and reflections at class pertaining to various topics they cover in TEE books that range from theological discourses about the triune God, atonement, Christology, creation, and providence to other topics such as Christian living and growth, Christian stewardship, family, money etc.

In our world characterised by diverse issues affecting the Church and society, such students of TEE have ample time to think through these issues at length and give examples of what is happening on the ground. Theological discussions and reflections not only sharpen each other but equip and open the scope of the laity to many other underlying issues that the diocese is wrestling with. Thus, the TEE discussions and reflections are ways and means that the diocese is equipping its laity for Christian ministry, as one respondent affirms, "through the TEE discourses and discussions I am able to appreciate the many dimensions of the same text of the Bible that may apply in life" (Respondent #08). From this excerpt, it is right to deduce that TEE discussions equip the laity to be theologically critical thinkers and as such begin doing theology from below. This implies that they began theologising in their own context and consequently confronted the underlying issues affecting them in the diocese. This is advantageous to the diocesan laity vis-a-vis those who joined theological seminaries since their set-up time is extremely limited for in-depth theological discussions and reflections. Burton could not hesitate to unfold one inadequacy of conventional theological education at seminary as, "there is limited discussion, the students have assigned reading and papers to prepare and can only spend a very limited time working to support themselves" (2000:6).

Equipping the lay people with leadership skills is another way the diocese is empowering the laity for Christian ministry. This is because in a diocese with a population of 36,292 Christians and 107 clergy, it is impractical for the clergy to serve effectively (Anglican Church of Kenya Diocese of Thika, 2015). This implies that the ratio between the clergy and laity is approximately 1:339; thus , the gap is too wide - insinuating that the day-to-day running of most local congregations in the diocese is in the hands of laity as clergy visit those congregations occasionally for sacerdotal services such as administration of sacraments. Therefore, the TEE has been instrumental in the diocese as far as bridging the glaring gap and empowering of the lay leaders is concerned. The testimonies of the diocesan laity who are doing TEE are impressive, as narrated here by one of them that, "through facilitation of our class, my leadership qualities have been greatly enhanced" (Respondent #08). This suggests that TEE remains an integral tool for equipping the laity in the diocese of Thika and should be sustained at all costs. Failure to support this programme is tantamount to weakening diocesan leadership and thus the future of Christian faith will remain at stake.

To this end, Oriendo commends dioceses to equip their laity through TEE since they, "offer spiritual oversight in the Churches, in the absence of a clergy" (2010:77). Therefore, through studying TEE materials, particularly the book entitied The Shepherd and his Flock, the laity are exposed to different leadership styles and roles, biblical qualities of a leader, and servant leadership, among other vital areas. This implies that the laity acquire the appropriate leadership skills in the Church and society. Moreover, out of their class discussions, they derive lessons from their own context and resolve how to address their leadership gaps in the Church and society at large.

Expounding the word of God is the central role of the Church of Christ. This implies that proper and effective ways of interpreting the word of God is at its essence. As such, TEE programmes become another means in the diocese of Thika of equipping its laity for Christian ministry. For with this programme, the laity are exposed to books such as Old Testament Survey, New Testament Survey, Studying the Book of John, Studying the Book of Mark, among others. All these books when learnt leave the TEE candidates with new knowledge on how to interpret the word of God and get the deeper meaning of a given text. This suggests that the laity are equipped with biblical exegetical and hermeneutical tools while reading the Bible. As Bible scholars, the laity in the diocese, according to Keith Anderson, "help them apply the teachings of the Bible to their own lives, to the ministry in the congregations, where they serve and to their ministry in the world" (1984). Thus, as a Church leader with enormous responsibility of preaching the word of God twice or thrice in a month, equipping them for Christian ministry is of paramount importance. Through TEE programmes, the diocesan laity assert that it, "helps in reading the Bible [and] understanding the Bible better" (Respondent #07).

The TEE programmes in the diocese are open to all people of all walks of life. This sees different people of different ages, gender, status, educational background, and ethnic groups all joining these classes to learn the word of God together. With their different gifts for the Church of Christ, they have an opportunity to share those gifts for the edification of the body of Christ. To Oriendo, he opines, "group members monitor one another by way of setting aside some minutes for fellowship, whereby every member is assigned a day to share from scriptures and testify" (2010:37). From this ministerial experience, their gifts are identified and manifested in the TEE class. This helps the group facilitators to know how those gifts can be appropriated in the diocese or the Church of Christ. Towards this, the TEE become a thriving ground for networking at local congregation, parish, deanery, archdeaconry, and all the way to the diocesan level. This thought is well captured by one diocesan respondent who was convinced, "synergy and network among TEE learners has been of immense benefit in many aspects" (Respondent #08). What has been phenomenal in the diocese is that pulpit exchange has been witnessed among the TEE students at local and parish level. This networking has enhanced partnership in mission among lay leaders in the diocese. The partnership has sometimes grown and spread to neighbouring dioceses who agree to have exchange programmes or visit the other diocese for benchmarking.

7. Some Setbacks to TEE Programme in the ACK Diocese of Thika as a Tool of Equipping Lay Leaders for Christian Ministry

As highlighted above, it is evident that TEE is imperative in the ecclesiastical setting for empowering and equipping lay leaders in the Church for Christian ministry. However, when the opposite happens, this phenomenon is detrimental to the Church of Christ. It is therefore in this line of thought that this article now embarks on exploring some setbacks that affect the integral role that TEE plays in the life of the diocesan laity.

7.1 Good Will of Church Leadership

The Church leadership is vital for the optimal functioning of any organisation; it is similar to the vital organ of human beings. When it functions properly, the person is healthy and alive, and this is the same thing in the visible body of Christ - the Church - as this is the body that envisions the life of the Church. While TEE has registered remarkable achievements in the diocese of Thika, there are some factors that are really withholding it from furthering its mission and vision. The good will of the diocesan Church leadership at local and parish level have been cited. Clergy, as the heads in these Churches, are singled out as a great hindrance to TEE programmes. This is echoed from diocesan respondents who maintained that:

"There was no support from clergy, and members [TEE students] felt abandoned" (Respondent #10).

"Morale was low since vicar was not interested, students were disappointed and thus disappeared" (Respondent #01).

Considering the above discourses from the diocesan local Churches and parishes, TEE facilitators/leaders, and members, it is right to infer that the good will of the Church leadership is wanting. Clergy, who should be on the frontline to support these groups in their parishes, are the very people who derail and sabotage the ministry of TEE; however, it is paramount in equipping lay leaders theologically. The consequences of this inadequate good will and minimal role of clergy in TEE programmes in their parishes is that lay leaders feel "abandoned" by their chief leader, who is supposed to offer all the necessary support of equipping them for Christian ministry in their parishes. This is because, when the lay leaders are equipped effectively for Christian ministry, they make the ministry of the clergy easier by becoming co-partners in the ministry. Moreover, they ensure the Christian ministry reaches as many people as possible since these lay leaders lives were the masses are who need to be enlightened with the Gospel of Christ. Thus, when clergy fail to support the lay leaders, what eventually happens is TEE as a tool for equipping and empowering lay leaders for Christian ministries collapses when the members are "disappointed", as Respondent #01 replies.

Besides clergy in the Church leadership as one obstacle to effectively equip the lay leaders in the diocese, their local and parish councils still have their portion. Diocesan TEE members are quoted as saying their major challenge is, "inadequacy of requisite support from the Church Council and its administration" (Respondent #08). This is despite this being the organ that is constitutionally mandated by the diocese to run the day-to-day life of the Church activities. The diocesan TEE lay leaders cite their lack of support as visibly evident when the council and its administration give no attention to their existence in the local Churches and Parishes, especially when there is, "no emphasis [of TEE and its impact] in the Church" (Respondent #01). Failure of these councils to recognise the work of TEE in equipping the laity in the diocese, makes follow up difficult. Thus, while the TEE has a good vision of the Church in effectively equipping its members for Christian mission, this setback has adverse effects on this noble ministry. As such, Nkonge could not resist the temptation of concluding that this failure results in, "making it hard for the poorly-trained evangelists and lay leaders to lead ... [and] such congregations face so many pastoral and administrative problems as the theologically untrained evangelist and lay leaders cannot effectively handle them" (2016:117).

7.2 Time Factor

The time factor is another impediment to effectively equip lay leaders for Christian ministry in the diocese. Though Libby Goodman (1990) believes that there is a correlation between time and learning outcome, the time located for this Christian ministry in the diocese is not adequate. The article was able to establish that coming into consensus in most TEE groups was a nightmare due to various responsibilities and commitments of the lay leaders in the diocese. This can be attested by Respondent #08 who states, "failure to unanimously agree on the time to have TEE" is a grave challenge in their local Church. Even when the allocated time is set, members cry foul since punctuality is not a vocabulary in most TEE members. This is attested by another member who argued, "time keeping by learners"" (Respondent #05) is a key challenge facing them as a group. To exacerbate this, the time allocated for TEE classes overlaps with the programme of the local Churches, especially for those who meet on Sunday morning or evening after the morning service.8 Thus, the members join TEE class when they are already worn out and this affects their concentration and the productivity of the students.

To this end, the article avers that quality time for effectively equipping these lay leaders for Christian ministry needs to be improved if the vision and mission of TEE pioneers is to be realised. The forerunners of TEE had in mind the importance of quality time among the learners since this gives them opportunity to have in-depth theological reflections and discussions. According to Burton (2000:6), this still stands as a greater advantage of TEE programmes in relation to those in theological seminaries who have limited time for discussions. This means when quality time is rare at TEE classes for laity, where contemporary and emerging theological issues should be discussed, the diocese ends up having half-baked lay theologians who instead of being resourceful to the Church will be more perilous to the Church than uneducated lay leaders. When it happens, de Gruchy's anticipation of having theologically sound lay leaders and congregations will be but a spiritual hallucination to the Church of Christ in the diocese.

7.3 Cost of TEE Literature

Although the cost of TEE has been thought to be pocket friendly to the global South Churches, this is implausible (Oriendo, 2010:15). This can be affirmed by some TEE facilitators who shared the cost of running TEE as one challenge their groups face. Their narratives are as follows:

"Some members lack funds to buy the books" (Respondent #02).

"Books are expensive and not everyone can afford them" (Respondent #07).

Following these discourses emerging from the field, it is evident that the cost of securing TEE books and other literature is a setback. Thus, in a context where the majority of the masses live on less than one dollar per day, this programme is halted because it is only a few that can afford it, despite TEE lifting all the barriers that hindered laity from doing theology. The matter in the diocese is escalated by failure of local and parish leadership that have no good will toward the programme. This means that the TEE members are not supported financially by most local and parish councils to cater for their training needs. Thus, the cost of TEE literature such as books and other related items impact the whole process of equipping and empowering laity for Christian ministry

7.4 Physical Space for Learning TEE

Researchers who study the relationship between space and learning argue that the two play an integral role in the well-being of the students. As such, learning takes place in a four-walled space, which Andrew Middleton describes as, "dominant teaching walls as being a defining feature of classroom" (2018:6). In this space, students have their teachers or facilitators who pass on knowledge to them, as well as a space where academic discussions and reflections take place. To Middleton (2018), he challenges this form of space for learning in the 21st century since it encloses learning and disconnects it from others' context. However, within the diocesan context, this is the only available option for learning TEE as a tool for empowering and equipping lay leaders for Christian ministry. This prompts some lay leaders to take their learning to the Church hall, Church offices or other designated space that is available. Unfortunately, these available spaces for learning TEE have their own shortcomings as diocesan TEE leaders identify some challenges they encounter in term of space as, "lack of reserved classroom of TEE studying" (Respondent #08). Another TEE leader laments their anguish in course of learning since, "sometimes missed a room to meet during class hours" (Respondent #09).

In nutshell, the space for learning TEE is a big setback in the diocese, which may leave one wondering how healthy TEE discussions and reflections take place in such an unconducive learning environment. Students may be psychologically set for class; however, along the way they miss a space to learn or are moved from one space to the other. What eventually happens is they become disoriented. Despite Hilary Hudges, Jill Franz and Jill Willis (2019:3) admitting that there is limited understanding about how physical space influences student learning in holistic and existential ways, one expects that TEE students will be ill-empowered and equipped for Christian ministry. This calls for provision by the local and parish leadership of physical space to the group. Such incentives by Church leadership will improve the students' morale and more so their effectiveness as Church leaders, for they will have ample time and a conducive environment to study the word of God.

7.5 Techniques of Evaluating TEE Exercises

The methods applied for evaluating TEE students is another drawback to this programme as a tool of empowering and equipping lay leaders. Though tests and exams were not the initial purpose of devising this alternative mode of theological education in ecclesiastical setting, with time this became inevitable. Unfortunately, some TEE members have dropped out from TEE classes due to testophobia and examinophobia. This is clearly articulated in some responses such as need to, "assure them that nobody can fail TEE as long as they attend classes, do book work, do weekly tests, attend discussion sections, and attempt the final exam" (Respondent #05). It is evident from this response that class attendance, TEE book work, weekly tests, class discussion, and eventually the end of book exams are the most common evaluating techniques in place for TEE students. While these options are modern trends today, what is clearly in this field is that the TEE department should consider all the possible options to cater for the diocesan needs. For example, those comfortable with academic evaluation or credentials to pursue this option could do so, while those taking TEE for spiritual transformation could be given that liberty. To this end, Oriendo concurs with the researchers who recommended upgrading TEE levels of education to cater for different interest groups with different academic credentials among laity. For he is convinced, "the ACK should consider developing more courses for the diploma and the degree levels" (2010:81) to cater for these emerging needs in the province.

8. Conclusion

In conclusion, the researchers argue that the future of African Christianity lies in the way the laity will be adequately equipped and empowered for Christian ministry. In the global North, the Church there was able to equip and empower its congregation to think in a theologically sound way. Its impact was felt when different evangelistic missions were established to reach out to other continents, especially the global South, with the word of God. This Church flourished in her mission since it had fully equipped and empowered its laity theologically. Thus, it remains a great challenge for the global South Church to do the same. It is arguably expected that with its theological power or dynamite, it will reciprocate by taking the gospel of Christ to the global North that is lost in secularisation and globalisation. We also argued that it is through TEE that recommendations for the African Church to embrace doing theology with the laity will be realised and eventually have theologically literate congregations. Failure to equip and empower the global South laity with theological education will be tantamount to permitting God's people to perish for lack of theological knowledge that is direly needed to address underlying issues affecting its people. Its success will amount to the Church of Christ fulfilling the Great Commission that Christ commanded the Church to preach and teach the gospel (see Matthew 28:16-20).

We continue to contend that the TEE that was introduced in Africa, particularly in Kenya, was an imported theological product that alienates its people that is thought to equip, empower and liberate. This means that the TEE in the ACK should be incultur-ated within its context to speak to the ACK adherents in their worldview. This suggests that the use of indigenous languages of the ACK adherents is of paramount importance for realisation of a self-theologising Church in Kenya. In summary, the article's point of departure is that the future of the TEE as a tool of empowering and equipping laity in the ACK solely depends on the good will of the Church leadership. With this good will, all the drawbacks highlighted will be addressed, since the Church leadership will give moral and financial support to this noble ministry in ecclesia, and space and time will be available for healthy theological discussions and reflections.

References

Oral Works

Published Works

ACK Diocese of Thika. 2017. Theological education by extension report to the Board of Education on 19th July. Diocesan Synod Hall, Thika. [ Links ]

_______. 2018. Diocesan TEE coordinator anniversary report. Diocesan Synod Hall, Thika. [ Links ]

_______. 2020. Board of Education Report to the Standing Committee of the Synod (SCOS) on 11th June, Diocesan Synod Hall Thika. [ Links ]

_______. 2020. Preparatory report of 11th ordinary session of the diocesan synod. Diocesan Synod Hall, Thika. [ Links ]

Anglican Church of Kenya, 2019. Decade strategy 2018 -2027: A wholesome ministry for wholesome nation. Nairobi: Uzima Press. [ Links ]

Burton, S.W. 2000. Disciple mentoring: Theological education by extension. Pasadena, California: William Carey Library. [ Links ]

de Gruchy, J. 2011. Transforming tradition: Doing theology in South Africa today. Journal of Theology for Southern Africa, 139, 7-17. [ Links ]

Gatungu, J. 2020. Telephone interview with the author on May 1st from Texas, USA. [ Links ]

Goodman, L. 1990. Time and learning in special education classroom. New York, Albany: State University of New York Press. [ Links ]

Houston, B. 2009. Missiological and theological perspectives on theological education in Africa: An assessment of the challenges in evangelical theological education. Presented at the Joint Conference of Academic Societies in the Fields of Religion and Theology, Session A11. 22-26 June 2009, University of Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Hudges, H. 2019. School space for students' wellbeing and learning: Insight from research and practice. Gateway Singapore: Springer. [ Links ]

Kinsler, F.R. 1981. The extension movement in theological education. Pasadena: William Carey Library. [ Links ]

Mabuluki, K. 2013. Theological education for all God's people: Theological Education by Extension (TEE) in Africa. In I.A. Phiri & D. Werner (eds.). Handbook of Theological Education in Africa, pp. 832-840. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications. [ Links ]

Middleton, A. 2018. Reimagining spacefor learning in higher education. London: Palgrave. [ Links ]

Nkonge, D. 2011. Equipping church leaders for mission in the Anglican Church of Kenya. Journal of Anglican Studies, 9, 154-174. [ Links ]

_______. 2016. The need for equipping lay Church leaders in the Anglican Church of Kenya for mission and ministry through Theological Education by Extension. Journal of Educational Policy and Entrepreneurial Research, 3(11), 112-124. [ Links ]

Oriendo, S.J. 2010. The Theological Education by Extension (TEE) programme of the Anglican Church of Kenya: A case study. Unpublished MA Education with Specialisation in Open and Distance Learning. Pretoria: University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Parson, G.H. 2018. Theological Education by Extension: Lessons from the past application for the Future. Retrieved from: https://www.rdwresearchcenter.org/post/2018/02/03/theological-education-by-extension-lessons-from-the-past-application-for-the-future (Accessed 28/04/2020). [ Links ]

Wahl, W.P. 2013. Towards relevant theological education in Africa: Comparing the international discourses with Contextual Challenges. Acta Theologica, 33(1), 266-293. [ Links ]

1 George Kiarie is a Lecturer of Religious Studies at Karatina University, Kenya. Email: kiariegeorge77@gmail.com; Postal address 1957 Karatina; Rev Mary Mwangi is an ordained Anglican priest and former diocesan TEE co-ordinator in Thika. Email: cikumaria13@gmail.com; Postal address 214 Thika. This article forms part of a special collection titled 'Urban Africa 2050: imagining theological education/formation for flourishing African cities'. The collection captures the outcomes of a research project with the same title, hosted in the Centre for Faith and Community at the University of Pretoria. This research project was funded by the Nagel Institute for World Christianity, based at the Calvin University, Grand Rapids.

2 Telephone interview with Bishop John Gatungu who served as priest in those years in the Diocese of Nakuru (01/05/2020).

3 Mombasa, Maseno North, Mount Kenya East, Nairobi, Nakuru, Mount Kenya Central, and Maseno South.

4 Of these 30 active TEE groups, 18 were from Kariara and Cathedral Archdeaconries where each had nine groups while 12 were from Mang'u and Ruiru Archdeaconry where each had six groups.

5 These groups are from Juja, Theta, Kenyatta Road, Membley (two groups), Murera sisal, Cathedral, Kabati Fly Over, Happy Valley, Kilimambogo, Swani, Mwagu, Gatura, Gatunguru, Gatuanyaga, Mugu-tha, Canon Hesbon, and Kiarutara.

6 Juja A & B, Fly Over Kabati A, Fly Over Kabati B, Kware, Cathedral Youth, Mwagu, Grey Stone, Gatungu-ru (Gatura), Kiarutara, Canon Hesbon, Gatura, Gatuanyaga, Mugutha, Thome, Gikono (Swani), Thika River Salama, Kamenu, Cathedral Town, Highland, Karangi, Ngoingwa, Witeithie, Thika Memorial, Karibaribi, High Level, Ndunyu Chege, and Kame.

7 de Gruchy, J. 2011. "Revisiting Doing Theology in Context: Re-assessing a Legacy". Journal of Theology for Southern Africa, 141, 24.

8 As one TEE member points out that they meet "odd hours of meeting on Sunday afternoon after long hours in Church" (Respondent #03).