Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Missionalia

On-line version ISSN 2312-878X

Print version ISSN 0256-9507

Missionalia (Online) vol.47 n.1 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.7832/47-1-335

ARTICLES

Giving an account of hope in South Africa. Interpreting the Theological Declaration (1979) of the 'Broederkring van NG Kerke'1

J.N.J. (Klippies) Kritzinger2

ABSTRACT

This paper analyses the Theological Declaration of the Belydende Kring (1979) in view of the South African context at the time. After sketching the credibility crisis facing black ministers of the Dutch Reformed 'family' of churches in the late 1970s, it outlines the vision of the Belydende Kring and the threefold purpose of its Declaration: an apologia to its critics, an exercise in contextual theologising, and an engagement with the 'fathers' of the Reformed tradition. The paper uses a 'praxis matrix' to explore the performance enacted by the Declaration, in terms of its own declared intentions.

Keywords: South Africa, Belydende Kring, Dutch Reformed Church 'family', confessional statements, Reformed tradition, Black Consciousness, praxis matrix, apologia, contextual theology, Confessing Church

1. Introduction

The Belydende Kring (BK)3 was an action group in the Dutch Reformed 'family' of churches that was established in 1974 and no longer functioned around 1993. Its twin objectives were to unite the Dutch Reformed Church (DRC) family of racially constituted churches and to witness prophetically against the political and economic injustices of the apartheid system4. In September 1979, the BK released a Theological Declaration to articulate its vision for the role of the church in South Africa.

This essay explores the BK Theological Declaration5 in the ecclesial and political context of the late 1970s in South Africa. In an earlier paper (Kritzinger 2010), I traced the influence of the BK Declaration on the origin and content of the Confession of Belhar6 by pointing out the verbatim agreements and other similarities between the two documents, but without exploring the theological content of the BK Declaration in any depth7. I return to the BK Declaration here to examine it as a creative example of contextual Reformed theologising in its own right, apart from the wide influence that some of its ideas attained through their inclusion in the Confession of Belhar.

I use a praxis matrix8 to analyse the particular performance9 of Christian faith that is expressed in the BK Declaration. This approach is based on several methodological assumptions that I have explained and used elsewhere10. It distinguishes seven dimensions of transformative Christian performance in a particular context, namely; agency, contextual understanding, ecclesial scrutiny, interpreting the tradition, discernment for action, reflexivity and spirituality. This use of a 'praxis matrix' to explore a historical document in its context is an exercise in missiological historiography. The matrix - in its original form of See-Judge-Act or the 'pastoral circle' - was initially used primarily in the mobilisation of Christians ('on the ground') for societal transformation11, but was later developed into an instrument for mis-siological reflection on the involvement of Christians in transformative mission ('on the balcony')12. I suggest that historical research on a 'confessional' document of a movement committed to societal transformation can best be done by means of an analytical framework that itself emerged from the praxis of transformative Christian witness and engagement.

My personal stance in relation to the theme of the essay is one of involvement. I was a member of the BK from 1979 and attended the conference where the BK Declaration was adopted. I acknowledge this bias - with all the opportunities and challenges it presents to truthful historical research - and I affirm that such an insider's perspective naturally invites critical analysis and contestation from alternative perspectives.

I dedicate this paper to Nico Botha, my long-standing friend, BK comrade and University of South Africa colleague, who has consistently voiced and lived the message of the BK Declaration and from whom I have learnt so much about its meaning. Together we remain 'prisoners of hope' in an increasingly depressing society and world.

2. The Dutch Reformed 'Family' of Churches

To understand the BK and its Declaration in context, it is necessary to know the background and nature of the Dutch Reformed 'family' of churches. Since much has been written about this, a brief sketch will suffice. The mission praxis of the DRC that emerged since the 17th century in South Africa gradually gave rise to separate churches based on culture-race-class, whose separate identities became increasingly distinct during the 19th and (especially) the 20th century. The Dutch Reformed Mission Church (DRMC) was formally constituted in 1881 and included congregations of all 'non-white' converts, however in 1951 the African congregations were separated from the 'coloured' congregations (which remained in the DRMC) to form the Dutch Reformed Bantu Church, later renamed the Dutch Reformed Church in Africa (DRCA). In 1968 the congregations in the Indian community were constituted as the Indian Reformed Church (IRC), later renamed Reformed Church in Africa (RCA).

These three 'daughter churches' (DRMC, DRCA, RCA) in what came to be called the Dutch Reformed 'family' of churches, were dominated by missionaries, who remained members of the white 'mother church' (DRC), while working in black congregations. All the black congregations were financially dependent on the white congregations in their vicinity for the erection of church buildings and the salaries of their ministers. A seminary to train African and coloured ministers, evangelists and teachers was set up as early as 190813 and the number of black ministers and evangelists grew steadily during the 20th century, as the members and congregations increased in numbers across the country. The political and economic developments in South African society had a lasting impact on the lives of the members of these churches, but initially the ministers remained largely passive and compliant in the face of the injustices they faced. Colonial policies since 1652 precipitated numerous wars and other acts of resistance from the side of indigenous communities, but through military and economic power the white minority managed to stamp its authority on the whole society. After the election victory of the National Party in 1948, the suffering of black church members increased exponentially, due to the panoply of oppressive laws and policies that came to be known as apartheid.

Due to the racist and paternalist praxis of the mission churches14, numerous secessions took place since 1875, giving rise to black-led 'Ethiopian' and Zionist churches. Those churches created a platform for the emergence of political organisations like the African National Congress (ANC) and workers' movements like the Industrial and Commercial Workers Union (ICWU), which started challenging government policies. It was especially the establishment of the Union of South Africa in 1910 (which excluded political rights to black citizens) and the Land Acts of 1913 and 1936, which caused growing resentment and resistance among black South Africans.

In that situation of growing tension and unrest, the DRC mission prided itself on producing black church members and ministers who were positively disposed towards Afrikaners and who trusted their good intentions in establishing separate churches and other institutions, as opposed to the 'troublemakers' [kwaad-stigters] trained by other churches, who were fomenting anti-government revolt in black communities. This is clearly expressed in a pamphlet defending the work of the Stofberg Gedenkskool against the critique of Afrikaners who were opposed to Christian mission and the education of black people:

We all know that many churches are working here and that all of them are serious about education; that is why the 'educated' all prefer to belong to other churches. So, what does it help to be overly cautious with the education of the native [die naturel]? Kadalie, Thaele, Mote, Mahabane and all the others of that quality are today crisscrossing the country, holding and attending congresses, even in Europe! They did not get their education at Stofberg. How are we now going to counteract them effectively? We all want the government to adopt strict measures... But we must be careful not to make 'martyrs and heroes' of them. We are moving on dangerous terrain here. We may stop their mouths in public, but who can control what they do in secret? So, what can be done? We must combat them on their own terrain with similar weapons. More evangelists, native ministers and teachers who bear our stamp are needed. Send us people from the Afrikaner farm [boereplaas], who received the right stamp from a farmer [boer]. We will give him the right kind of education here. Their influence is counter-poison [teegif], excellent counter-poison. As far as we could ascertain, not one of our alumni has ever made a hostile remark about us; on the contrary, they defend us [Britz, 1927:19 (my translation, italics in the original)].

The message is clear: Black ministers, evangelists and teachers who qualified at Stofberg bore the 'stamp' of pro-Afrikaner DRC interests. They were selected and trained to defend the DRC's race policies and practices in the black community, to act as antidote to the poison of troublemakers like Clement Kadalie and others. The Afrikaner politician, M.C. de Wet Nel, spelled out the broader political ramifications of this kind of mission in 1958:

[O]ne of the main reasons why many people are still cold and indifferent to mission work is its political significance... If the Afrikaans churches succeeded in bringing the Blacks over into a Protestant-Christian context, South Africa will have a hope for the future. If this does not happen, our policy, our programme of legislation and all our plans will be doomed to failure (quoted in Bosch, 1985:68).

As resistance to apartheid rule grew in the black community from the 1950s onwards, the DRCA and DRMC did not remain unscathed. A group of coloured ministers in the Western Cape and their congregations left the DRMC in 1950 to form the Calvyn Protestantse Kerk, in protest against the introduction of apartheid legislation and the passivity of the DRMC leadership to criticise or oppose it15. The majority of DRMC and DRCA ministers and congregations remained in the DRC family, but found themselves in an increasingly awkward position.

Three factors enforced conformity: Firstly, their theological training - which had taken place in Afrikaans - put a distinct subservient 'stamp' on their preaching and ministry, which they had internalised as loyal church workers. Secondly, the dominant role of white missionaries in the structures and decision-making processes of the 'daughter churches' made it difficult for a black minister to bring about change in the church's policies and procedures. Thirdly, the financial dependence of black congregations on subsidies from white congregations or presbyteries held black ministers hostage. Whenever a black minister criticised the status quo in church or state, he was warned that he risked the withholding of his salary.

At the same time, there were strong factors eliciting resistance. In the first place, their own humiliation at the hands of racist policemen and government officials, as well as the paternalistic treatment of white missionaries created deep-seated resentment. Secondly, their constant pastoral exposure to the suffering of the members of their congregations weighed heavily on their consciences. Thirdly, the responses of other church and community leaders became increasingly hostile and dismissive.

Since the black community at large did not distinguish between 'daughter' and mother' churches, they were labelled collectively as 'the government church.' In that context, DRMC and DRCA ministers were seen as 'government stooges' and collaborators with apartheid.

The rise of Black Consciousness in the early 1970s created a groundswell of popular resistance against government policies and inevitably created tension between the 'daughter churches' and the 'mother church' - but also within the 'daughter churches' between conservative and critical ministers. As DRCA and DRMC ministers became politically conscientised, particularly in urban townships across the country, they became increasingly critical of DRC mission praxis. A South African Council of Churches (SACC) document from September 1971 commented as follows on the manifestations of Black Consciousness in different churches (Mukuka, 2008:189):

These events show a definite trend in thinking of black churchmen in South Africa. That black Catholic priests, generally regarded as 'conformists' and black ministers of the NGKA who have been called 'stooges' took a lead in the 'revolts' suggests a growing degree of discontent amongst black Christians.

This simmering discontent among ministers of the DRMC and DRCA in the early 1970s led to the establishment of the BK in 1974.

3. The Belydende Kring

The organisational origin and development of the BK has been researched else-where16. It is only necessary to emphasise that the origin and growth of the BK was a response to a deep-seated embarrassment experienced by black ministers in the DRC family regarding their politically compromised position in the black community. From that response, flowed a desire to affirm the Christian message as they believed it - at a personal, church and broader community level. This motivation is clear from the BK aims, which were formulated in 1974 at its inception:

• To proclaim the Kingship of Jesus Christ over all areas in church and in state, and to witness for his Kingly rule;

• To achieve organic church unity and to express it practically in all areas of life;

• To take seriously the prophetic task of the church with regard to the oppressive structures and laws in our land and to take seriously the priestly task of the church with respect to the victims and fear-possessed oppressors who suffer as a result of the unchristian policy and practice in the land;

• To let the kingly rule of Christ triumph over the ideology of Apartheid or any other ideology, so that a more human way of life may be striven for;

• To promote evangelical liberation from unrighteousness, dehumanisation and lovelessness in church and state, and to work for true reconciliation among all people;

• To support ecumenical movements that promote the kingship of Christ on all levels of life17.

This set of aims presents an integration of three strands: a) traditional Reformed theology (prophet-priest-king, 'the kingship of Christ on all levels of life'); b) an ecumenical commitment; and, c) a strong contextual dimension of promoting 'evangelical liberation' from injustice to overcome 'the ideology of apartheid'. As the overall praxis of the BK has been analysed in other publications, I move on to an analysis of the BK Theological Declaration.

4. The Belydende Kring Theological Declaration (1979)

Some background information is necessary before examining the text of the BK Declaration itself. Its drafting was proposed by Rev C.J.A. (Chris) Loff in a paper presented to the national BK conference at St. Peter's Seminary in Hammanskraal in September 1979 (Loff, 1979a). The conference plenary mandated Loff and a small team to draft a declaration overnight and it was adopted the following day. The document was drafted in Afrikaans and presented to the conference in both Afrikaans and English18.

The BK Declaration was initially not circulated very widely. It was published in the official BK journal, Dunamis (BK, 1979; BK, 1981), and remained relatively unknown until Dr Lukas Vischer of the World Council of Churches (WCC) included it in a publication on contemporary Reformed confessions (Vischer, 1982:22). After that, it became better known and made a significant contribution to the content of the Belhar Confession. The full text19 of the Declaration reads as follows:

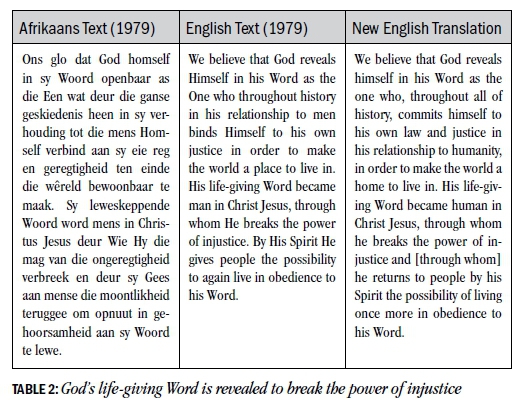

1. We believe in the God and Father of Jesus Christ who upholds the whole universe by his Word and Spirit. He struggles for his own righteousness which becomes visible in the obedience of people in their actions towards God and their neighbours. However, people have fallen into disobedience, which means the rejection of God's righteousness with regard to God and fellow man. In this respect, God chooses constantly for his own righteousness and consequently stands on the side of those who are victims of injustice

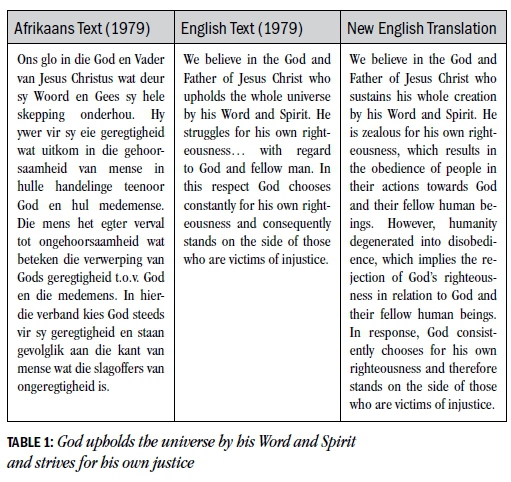

2. We believe that God reveals Himself in his Word as the One who throughout history in his relationship to men binds Himself to his own justice in order to make the world a place to live in. His life-giving Word became man in Christ Jesus, through whom He breaks the power of injustice. By His Spirit He gives people the possibility to again live in obedience to his Word.

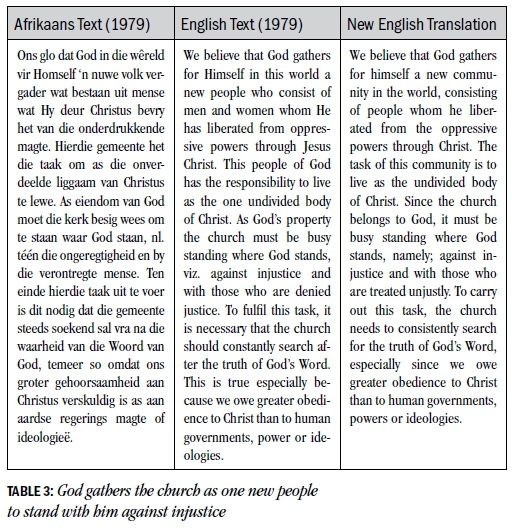

3. We believe that God gathers for Himself in this world a new people who consist of men and women whom He has liberated from oppressive powers through Jesus Christ. This (sic) people of God has the responsibility to live as the one undivided body of Christ. As God's property, the church must be busy standing where God stands, viz. against injustice and with those who are denied justice. To fulfil this task, it is necessary that the church should constantly search after the truth of God's Word. This is true especially because we owe greater obedience to Christ than to human governments, power or ideologies.

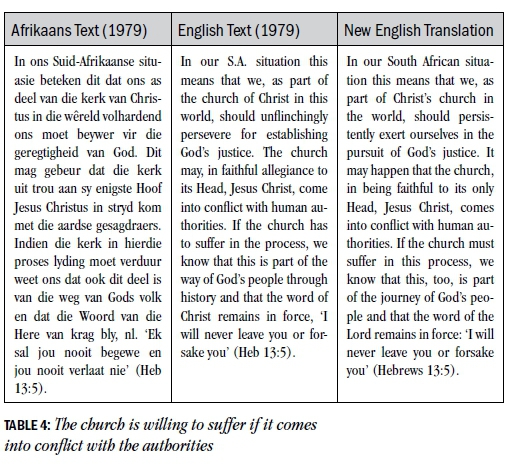

4. In our S.A. situation this means that we, as part of the church of Christ in this world, should unflinchingly persevere for establishing God's justice. The church may, in faithful allegiance to its Head, Jesus Christ, come into conflict with human authorities. If the church has to suffer in the process, we know that this is part of the way of God's people through history and that the word of Christ remains in force, "I will never leave you or forsake you" (Heb 13:5) (BK, 1979:3)20.

I will interpret the Declaration by reading 'behind' the text, 'in' the text and 'in front of' the text to trace the praxis in which it was embedded and which it promoted.21

5. The Praxis of the Belydende Kring Declaration

As indicated above, the praxis matrix identifies seven dimensions that characterise Christian actions aimed at societal transformation. Each dimension of BK praxis, as reflected in the 1979 Declaration, will be discussed in turn. It is possible to start with any of the dimensions but in this essay, it seems wise to start with Discernment for action, to explore firstly the reason why the Declaration was drafted, as well as its intended impact and audience.

5.1 Discernment for action

Why did the BK decide to issue a Theological Declaration? Additionally, how did that motivation shape its content? As indicated above, it was Rev Chris Loff who proposed the drafting of the Declaration in his paper presented to the BK conference in September 1979. To understand the rationale for his proposal, we need to examine the three points that he postulated in his paper, which was presented in Afrikaans, entitled: Predikant en teologie [Minister and theology].

Firstly, the purpose of a Ministers' Fraternal [broederkring] is to be effective in what it aims to do. As an organisation of ministers of the Word, its effectiveness should be measured in terms of service to the kingdom (reign) of God, which means obeying God and seeking God's glory. As a covenanting God, God seeks peace on earth through justice. Whenever anyone works to achieve a more dignified human life for the poor and the weak, this is seen as signs of the reign of God: "When people aim at achieving the wellbeing-salvation22[heil] of others in the name of the King, those workers make it clear that they are obeying the Saviour" (Loff, 1979a:17, my translation). For a ministers' fraternal, that means above all to 'do theology' together, which means studying Scripture and communicating it relevantly in a particular context (1979a:17). Theology is not the sole preserve of professors who write complicated books; it is the task of everyone who believes, and it involves finding answers to the urgent questions of the day. Theology therefore must be 'reality-directed' [werklikheid-gerig] and involves reading the newspaper as much as the Bible (quoting Karl Barth). Loff (1979a:18) illustrates this point by referring to the Pfarrernotbund [Ministers' emergency league] that was established by Martin Niemöller and other colleagues in Germany in 1934 during the church struggle against Hitler's National Socialism (Loff, 1979a:18, my translation):

This Pfarrernotbund was primarily involved in doing theology.23 The Barmen Declaration is a theological declaration through and through. But in their situation these people tried to find answers to their questions. Doing theology in such an ostensibly hopeless situation did not consist only of talking and writing ... From their meagre belongings the people around Niemöller scraped money together to help ministers who were being persecuted more intensely than they were".

Loff implied that the BK's first priority - as a Ministers' Fraternal - was to develop theological answers to the burning questions facing the DRC family in South Africa in 1979; its second priority was to share material resources with those colleagues in ministry who were worse off than themselves. The BK did in fact have a pension fund, with overseas support for retired ministers and evangelists of the DRCA (and their families), who received an extremely small church pension. There was also a Congregational Support Fund for DRMC and DRCA ministers and evangelists whose salary subsidies had been withdrawn by the DRC funding bodies due to their opposition to apartheid.24

The second point of Loff's paper was that a Ministers' Fraternal should engage in an ongoing and in-depth conversation with the Reformed tradition, despite the fact that we are unable to agree with everything our 'fathers' (like John Calvin) have written. For Loff (1979a:19), the BK is "the ideal space in which we can conduct our theological task. Study groups and working groups are the ideal activities for ministers who are running around the whole day and who sometimes don't know whether they are coming or going". Attaining greater theological depth is essential to address the challenges facing the DRC family. Loff gives an example of how a good knowledge of Dutch developments in Reformed church polity can help to deconstruct inadequate proposals (like that of an 'umbrella synod' instead or organic church unification), with the claim that it is based on 'true Reformed principles' coming from the Netherlands. This raises a crucial dimension of the role that the BK played: It was a critical-creative theological space where black ministers of the DRC family empowered one another, with the help of Dutch churches and universities,25 to 'beat apartheid theologians at their own Reformed game'. By studying the Reformed 'classics' from the Netherlands, Switzerland and Germany in depth, BK ministers were able to see through the false arguments of theological apologists for apartheid and develop an alternative theological vision from within the Reformed tradition.

In the same breath, Loff pointed out the dangers of allowing one's theological agenda to be dominated by one's own situation. He reminded his audience of the theology of the German Christians at the time of Hitler and the "racists who... try to let the Bible speak a racist language" and who do "Ham and Babel theology" to justify apartheid". He warned that "the oppressed persons can in turn very easily follow the same method with another purpose", thus leading not to theology but to "group-centred speculation, which is no better than an echo of apartheid theology. To counter this danger, an ongoing engagement with the 'fathers' of the Reformed tradition - but also with a wider community, to include Martin Luther and many others - is necessary. That will also help ministers avoid the pitfall of merely repeating biblical concepts like reconciliation, which leads to a superficial understanding of it as "a sentimental, unreal settling of deep-seated differences", thus avoiding the challenge of the cross of Christ (Loff, 1979a:20). For Loff, the 'bitter' death of Jesus on the cross confirms the truth that reconciliation is not cheap - and that it is impossible without justice.

The third section of Loff's paper is devoted to a proposal that the BK should draft a theological declaration. He starts by pointing out that the church learnt early in its life to express its faith in concise formulations to help its members know what they believe and to aid them for giving an account to outsiders of the hope that is in them (alluding to 1 Peter 3:15). He points out that it later became necessary for the church to expand its confession in response to new challenges, either from the outside or due to doctrinal contestations within the church. One thing was constant, however, on this confessing journey of the church: "[A] confession of faith is always called forth in times of crisis" (Loff, 1979a:20, my translation). After a reference to the important role that the Barmen Declaration played in Germany "to provide guidance in the times when persecution and suffering increased," Loff (1979a:21, my translation) states:

In our situation it has perhaps become necessary for our Ministers' Fraternal [Predikante Broederkring] to attempt something like this. We are aware of the serious efforts to discredit our organisation. Impressions are wilfully created to convince people that this is a movement with extremely dangerous objectives, which is inspired by motives foreign to the Bible. We cannot simply act as if we don't care about the smear campaign... It is in the interest of us all not only to have a set of basic principles but also an articulation of our faith so that we can respond in a succinct and concise way to our questioners, both honest and malicious.26

Loff's proposed theological declaration had a threefold objective. Firstly, it would serve an apologetic purpose to try and clear the name of the BK as an organisation, in response to its critics. In a follow-up article after the release of the Declaration, Loff (1979b:13) explained that the apologetic purpose of a Christian confession is to give an account of the hope within a believing community, in response to sceptical or aggressive outsiders. In the case of the BK, this referred not merely to people outside the church, but also to church members (and leaders) who opposed the praxis of the BK. He referred to them as 'malevolent informed' critics (Loff, 1979b:14).

Secondly, according to Loff (1979b:13), Christian confessions also had a pastoral purpose, namely; to clarify to members what they believed, thus deepening their unity and identity. So, another purpose of the proposed declaration would be to stimulate ministers in the DRC family to engage more seriously with the Reformed tradition in the South African context, posing to them anew the challenge of being Reformed in South Africa. Boesak (2015:128-129) in an interview on the role of Beyers Naudé, spoke in the following way about the BK as the space:

[w]here we, for the first time, made the distinction between a church with a confession and a confessing church. So, you have a church with a confession on paper and 'dit verbind jou aan die kerke van alle eeue' [it binds you to the churches of all time] and all that stuff, but it did not mean a thing. But when you become a confessing church in which you live out your faith among the challenges of everyday life - that was one of the things that Beyers made us understand.

Thirdly, the purpose of the proposed declaration could be seen as drawing more Reformed ministers into the BK, or at least into a more justice-oriented Christian praxis. The political conformity and apathy of most ministers in the DRC family was of serious concern to the BK and one of the reasons why it set up a theological journal (Dunamis) was stated as follows (Boesak 1977:2):

We hope to see Christians and the church involved in the confrontation with racism, prejudice, injustice and the threats to our freedom. We want to challenge the apathy of so many in the church and the inclination to be silent about what is wrong and to speak about the things that are really peripheral.

Loff (1979b:14) believed that a BK declaration could possibly draw some 'benevolent uninformed' questioners into a process of doing serious theology, through an ongoing, in-depth engagement with the Reformed (and the wider ecumenical) tradition.27

5.2 Agency

Who were the authors 'behind' the Declaration? To suggest, as I have done so far, that Rev Chris Loff was the main protagonist and author of the BK Declaration is simplistic, since it misunderstands the nature of the BK and misrepresents the dynamics operating within it as a ministers' fraternal. The term 'communal authorship' which I used in an earlier paper to describe the complex process through which the Belhar Confession was produced, applies here, too (Kritzinger, 2010). It isn't possible to trace all the role-players that shaped the agency of the BK in developing its theological response to the dominant Reformed theology that created and supported apartheid, but a few key contributors to this process need to be mentioned.

The first factor was the creative interaction within the BK itself. When the BK was formally established in December 1974 it consisted exclusively of DRMC and DRCA ministers, but by 1979 several RCA ministers had also joined. The BK was deeply influenced by the Black Consciousness Movement, but it did not exclude white ministers serving in the black churches, provided they fully supported the BK's aims and activities.28 In that sense, the BK observed the Black Consciousness adage that blackness is not about pigmentation but about a way of life and a commitment to justice. The ongoing interaction between BK colleagues in conferences and discussions, coupled with pulpit exchanges to introduce them to one another's congregations, created a space where they could share their respective experiences of apartheid and their unique insights into the gospel.

Another factor was the role that the Christian Institute (CI) and the SACC played since the 1960s to raise a prophetic Christian witness against apartheid policies. Beyers Naudé was an important role model for black ministers of the DRC family to develop the courage to speak out against injustice and to adopt self-reliance policies as black congregations in relation to white funding congregations. A number of DRCA ministers were employed by the CI during the 1960s and the CI's journal Pro Veritate also played a role in shaping the theological thinking of black ministers. The BK joined the SACC as an observer and became an integral part of the ecumenical anti-apartheid community. Dr Allan Boesak, who served as president of the BK during the late 1970s, was invited on different occasions to present keynote addresses at SACC annual conferences. Through constant interaction with other theological partners in the South African ecumenical movement, the BK developed its theological voice.

Another determining factor was the fact that a significant number of black ministers in the DRC family received scholarships to study in the Netherlands and the USA. If a black South African wished to enrol for postgraduate studies in Reformed theology in the 1970s, he had to go to Europe or the United States of America, as no DRC Faculty of Theology admitted black students until 1990.29 Between 1970 and 1993, a total of 22 South African black ministers studied in Kampen (Van Oel, 2011:166f), seven of whom obtained doctorates and 15 completed the doctorandus30programme.31Even though there were many Dutch theologians and church leaders who supported apartheid theology in the first half of the 20th century, out of sympathy with their 'white brothers' in South Africa, by 1972 the tide had turned, as Erica Meijers (2008) has convincingly demonstrated. The university scholarships and church support groups for black ministers and their families during the 1970s and 1980s were concrete expressions of solidarity with the black Reformed churches in South Africa, to help develop black leadership in the interest of a prophetic critique of apartheid and in pursuit of church unification between the racially constituted churches. When considering the kind of theological agency that developed in the BK during the 1970s, the Dutch theological factor should not be underestimated.

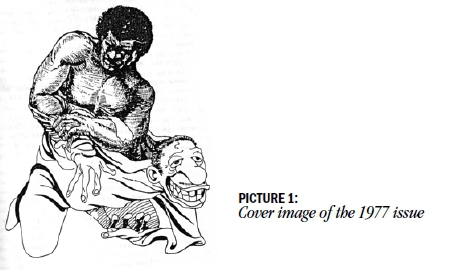

Another factor shaping the BK's theology was the reality of political oppression and the growing resistance against it in the black townships across South Africa. The Soweto student protests of 16 June 1976, which spread rapidly across the country, marked a turning point for black communities and presented many challenges to black churches. Ministers were involved in counselling the families of young activists killed by security forces and took part in their funerals, although they were by no means in control during the funerals since they usually became highly politicised events with a large security presence. Most congregations were reluctant to become too overtly involved in the protests, due to the high casualties involved, but young people exerted pressure on their parents and on church leaders to support 'the struggle'. The death of Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko at the hands of security police in September 1977 and the resulting protests increased the political tension in the country. raised the political temperature even higher. The subsequent banning in October 1977 of all organisations with links to the Black Consciousness Movement, including the CI, deepened the political crisis and the challenge that it presented to Reformed theology. The BK responded by starting a theological journal, Dunamis, with the sub-title 'Witness for a struggle for a relevant church', to provide theological guidance to its members as well as to a wider ecumenical audience. The first issue appeared in the third quarter of 1977, with the following image (see Picture 1) on the cover:32

This evocative portrayal of someone stripping off the false identity of a 'non-white' clown to reveal an assertive and self-aware black human being was a powerful way to start a journal. This liberational emphasis was confirmed by the first editor, Boesak (1977:2), in his opening editorial:

Dunamis wants to be a forum for theological discussion which will take full account of the reality in which we have to live. Christians in the Third World have had enough of theologies which had the function of justifying oppression and exploitation. We have had enough of theologies that wished only to stabilize the status quo and theologies that lacked the evangelical courage to speak a truthful and relevant word for our lives. We do not purport to have all the answers to all the difficult problems and for every facet of our complicated situation. We are determined, however, through faith grounded in the liberating word of Jesus Christ, to be involved. We want the Church to be meaningfully involved.

When surveying the contents of Dunamis between 1977 and 1979, one can see a BK consensus developing regarding the theological stance required of Reformed theologians in South Africa at the time. There were differences of emphasis between individual authors, as can be expected, but the overall thrust is clear and that consensus found expression in the BK Declaration of 1979.

To conclude this section on agency, it is important to look more closely at the drafting committee that was appointed by the BK conference to write the declaration. It included Alex Bhiman, Frikkie Conradie and Shun Govender, but there may have been one or two other colleagues present.33 All three black churches (DRCA, DRMC, RCA) were represented and the committee consisted of intelligent and committed young theologians in their early 30s, with only Loff who was their senior by a few years.34 They had only one night to complete their work, so there was no time for lengthy discussions or background research. What they produced was in their minds and at their fingertips. It seems as if profound prophetic documents are always formulated 'on the run' and 'after sundown', without the benefit of extended time or available literature.35 Such a declaration 'comes pouring out' of a mind (and then a community of minds) steeped in spiritual and theological virtues over years of formation, through ongoing action and reflection. Samuel Wells (2004:73) quotes the statement attributed to the Duke of Wellington: "The battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton", to make the point that good decisions or faithful performance in a crisis situation depends less on decision-making skills than on virtues that have been inculcated and internalised over years of practice and reflection.36 This is abundantly evident in the way the BK Declaration was produced overnight by a small group of Reformed theologians.

5.3 Interpreting the tradition

The Declaration consists of four short articles which can be summarised as follows:

1. God upholds the universe by his Word and Spirit and struggles for his own justice;

2. God's life-giving Word is revealed to break the power of injustice;

3. God gathers the church as His new people to stand with Him against injustice;

4. The church is willing to suffer if it comes into conflict with the authorities. The input of Chris Loff is clear here. When he proposed the drafting of a Declaration to the conference, he suggested that it should say something about "God, his Word and his Church" (Loff, 1979a:21, my translation). The first three articles of the Declaration are based on this suggestion, focusing on God, God's Word and the Church respectively, while the fourth article addresses perseverance in the face of suffering for justice.

It is impossible to do a complete genealogy of all the themes in the Declaration or give a detailed exposition of them. The Declaration, consisting of a mere 359 words in Afrikaans and 344 in English, is the tip of a proverbial iceberg thus I will limit myself to three questions, taken from Loff's own terminology: a) How did it provide an apologia to the BK's critics, by giving an account of the hope living among its members? b) How did it conduct 'reality-directed', contextual and pastoral theological reflection? c) How did it engage the 'fathers' of the Reformed (and the broader Christian) tradition? In other words, I do not evaluate the Declaration extrinsically but interpret it intrinsically, in terms of its own intentions and stated purposes.

Firstly, it is important to make a few comments on translation. The Dutch/Afrikaans concept geregtigheid, like the Hebrew mishpat and the Greek dikaiosyne on which it is based, can be translated into English as either righteousness or justice.37 These two English terms belong in different semantic fields, although there is some overlap between the two: Righteousness suggests moral uprightness and obedience to God in general, whereas justice focuses on obedience to God through eliminating discrimination against weak and vulnerable groups in public life. Considering that there are other translation issues, I developed a new English translation and placed it alongside the Afrikaans text and the original English translation. This procedure does not suggest that the 1979 English text (as published in BK, 1979 and Vischer, 1982:22) is 'inaccurate'. It is only by restoring the two missing sentences to the Declaration that it constitutes an 'improvement' on the English text of 1979, since it seems clear that those two sentences were omitted accidentally in the translation process (Kritzinger, 2010:219-220).38

I refrain from calling the Afrikaans text the 'Afrikaans original', as I did in my 2010 article, as it is unlikely that the committee first finalised the text in Afrikaans and then translated it into English. The composition of the committee made that unlikely. It is quite possible that during the discussions of the committee (which would have been in English), certain phrases were added to the English version and then translated into Afrikaans. In other words, I imagine that in the production of the two parallel texts, the primary translating 'movement' was from Afrikaans to English, but that there was also a movement from English to Afrikaans, at least with reference to certain phrases. The basic structure of the Declaration was conceived by Loff before the committee met, since he had already proposed it in his paper to the conference (Loff, 1979a:21) and most of the expressions have an Afrikaans 'ring' to them,39 but I don't claim that my new English translation is a 'more accurate' English rendering of the Afrikaans original, since the two parallel texts most likely emerged out of a bilingual process of negotiation. Since the figure of Chris Loff loomed so large in the process, however, the dominant movement was probably from Afrikaans to English and for that reason I regard it as helpful to do a new English translation, but only as an interpretive device.

In my translation, I did not eliminate the instances where male exclusive pronouns were used to refer to God or humans. Nor did I add '(sic)' to each such instance. If I were to prepare a text for public use today, this would amount to collusion with the gender-insensitive language, but my new translation is merely an attempt to reconstruct the meaning of the text as written in 1979.

(a) How did the Declaration provide an apologia to the BK's critics? Firstly, it affirmed catholic truths about God as creator and sustainer of the universe, about the Fall of humanity into sin, and about the intrinsic relatedness between loving God and loving others. It also adopted the traditional 'creedal' approach by starting its first three articles with "We believe in God..." and "We believe that God...". All of this is reassuringly orthodox, to both benevolent and malevolent questioners.

(b) In what sense was this 'reality-directed', contextual and pastoral theological reflection? The final sentence pushed the boundaries of traditional 'DRC family' theology, by connecting God's righteousness with God's choosing to stand "on the side of those who are victims of injustice". This connection between moral uprightness (geregtigheid in the general sense) and social injustice was born out of an engagement with the realities of apartheid South Africa. It implied a 'farewell to innocence'40 and the adoption of a social ethic as the horizon within which personal ethics find their proper place. This notion is only mentioned in the first article and spelt out in the next two.

The notion that God chooses to stand on the side of the victims of injustice was a pastoral response, born out of the reality of black township life where suffering communities read the Bible from within their experience of humiliation and exploitation, hearing God's assurance of unfailing love and compassion. It was probably also influenced by the affirmation of God's 'preferential option for the poor' in Latin American liberation theology. I return to this 'standing' of God in my discussion of Article 3.

(c) How did the Declaration engage the 'fathers' of the Reformed (and the broader Christian) tradition? In addition to affirming catholic Christian doctrine, the first article also contained the intriguing statement that God is "zealous for his own righteousness/justice" [Hy ywer vir sy eie geregtigheid], which is rather difficult to interpret. It may well be that Loff encountered this expression in the writings of one of the Dutch theologians, whom he met in the Netherlands, but I wasn't able to locate the origin of this expression. It has a Barthian ring to it, though, since it emphasises God's sovereign activity, 'vertically from above' in human history. God is understood not as a deistic 'First Mover' or 'clock winder' but as a history-making God who is actively involved in human lives. This is also clear from the fact that the divine zeal for 'his righteousness' results in human obedience in relation to God and others: God strives zealously- with the result that people become obedient in their relationships. This is an affirmation of the consistent emphasis of the Reformed 'fathers' on the intrinsic 'correlation' between God's gracious initiative and human responsibility.41

When considering the engagement with the 'fathers' of the faith, one should also ask: How deeply did the Declaration drink from the wells of Scripture in this article? There are too many allusions to Scripture in the article to mention here, but one issue stands out: God's zeal for God's own justice/righteousness. The 'zeal' of God is often associated with God's judgment on disobedient Israel or on the nations. However, in Isaiah 9:7, a close connection is made between God's zeal and justice/righteousness, which could be the source behind the wording of this article. It is said that the promised Davidic heir will "establish and uphold it [the throne of David] with justice and with righteousness from this time onward and forevermore. The zeal of the LORD of hosts will do this" (Isaiah 9:7).

a) How did the Declaration provide an apologia to the BK's critics? As in the first article, the Declaration used recognisably Reformed terminology. The creedal language, emphasis on God's initiative, notion of God's revelation "in his Word," trinitarian texture, incarnation, and responsibility of living in obedience, all ring true to Reformed orthodoxy. This article would have reassured the 'benevolent uninformed' members, and perhaps silenced a few 'malevolent informed' ones.

(b) In what sense was this 'reality-directed', contextual and pastoral theological reflection? A central issue is the atonement theory reflected in the declaration. In terms of the typology developed by Gustav Aulén (1931), this is not an Anselmian ('Latin' or 'objective') understanding of atonement in which the eternal anger of God over human sin is borne vicariously by Christ; it is closer to Aulén's 'classic' or 'dramatic' theory, in which "Christ - Christus Victor - fights against and triumphs over the evil powers of the world, the 'tyrants' under which mankind is in bondage and suffering, and in Him God reconciles the world to Himself" (Aulén, 1931:4). In a situation where black Christians are not only sinners but also - and perhaps primarily - the sinned-against, a one-sided Anselmian atonement theory does not mobilise believers to affirm their human dignity or to strive for justice in society. The cross and resurrection of Jesus are not mentioned, perhaps because the earthly life of Jesus of Nazareth is usually thereby relegated to a mere prelude to 'the real reason why he came into the world', namely; his vicarious death on the cross. A recovery of the earthly life of Jesus is part of this contextual theology, since it is in his miracles and exorcisms that it becomes visible how God "breaks the power of injustice" through him, even though that culminates in his resurrection from the dead. This is good news to suffering and oppressed Christians: God is at work in the world, committed to his law and justice, standing with those who are suffering, breaking the power of injustice that is keeping them in bondage.

(c) How did the Declaration engage the 'fathers' of the Reformed (and the broader Christian) tradition? In the use of the term 'the Word', one can perhaps see the influence of Karl Barth's view on the three forms of the Word: God's eternal Word revealed in Jesus Christ, God's Word in the Bible, and God's Word in the preaching/communication of the church. The emphasis on the earth as God's oikos - 'a home to live in' - instead of merely a 'vale of tears' or a preparation for eternity ('This world in not my home') is deeply Reformed in its focus, but also responding to the recent emphasis in ecological theologies on earthkeeping as a Christian calling. Typically, Reformed too is the 'third use of the law' that is evident in the way the work of the Holy Spirit is explained: Giving believers the possibility of "living once more in obedience to his Word".42

What are the key scriptural allusions that inform this article? The first sentence is based on numerous Old Testament passages, like Psalm 33:5, 89:14, 103:6 and 140:12, where God's commitment to justice and righteousness are emphasised. But one passage (among many others) that combines God's justice with the notion of God's compassionate closeness is Isaiah 30:18: "Yet the LORD longs to be gracious to you; therefore, he will rise up to show you compassion. For the LORD is a God of justice. Blessed are all who wait for him!"

In the second sentence of the article there seems to be a clear allusion to Luke 4:16-21, where Jesus applied the prophecy of Isaiah 61:1-2 to himself and where the coming of God's anointed messenger is linked with breaking the power of injustice and a new obedience brought about by the Spirit of God.

(a) How did the Declaration provide an apologia to the BK's critics? Here, too, the language is recognisably biblical and Reformed, but it depends on how one interprets 'the oppressive powers', 'standing where God stands' and 'greater obedience to Christ'. In a pietist-Reformed reading, which became dominant in the DRMC and DRCA due to the influence of generations of white missionaries and the use of hymnals that contain a great deal of individualist and escapist spirituality, these phrases can easily be rendered 'innocent' by spiritualising them.43 It is also possible, however, to read these phrases as a call to resist the oppressive racist policies of apartheid and to be prepared to suffer for such a 'standing with' suffering people in their struggle to be human. That is clearly the way in which the BK meant this article to be understood, but it becomes clear once more that theological formulations don't hang in the air. They are always embedded in a particular performance of the gospel, as I pointed out earlier, so this Declaration can only be understood together with the other dimensions of the BK's praxis. The way in which this article formulated the BK's 'stand' may have assured the 'benevolent uninformed' members, but it would probably not have convinced the 'malevolent informed' ones.

(b) In what sense was this 'reality-directed', contextual and pastoral theological reflection? This article is arguably the heart of the Declaration, since it spells out what the church should be in response to what the first two articles confess about God. The first sentence, containing two indicatives, confesses God as the one who takes the initiative to gather and liberate the church, while the following three sentences, containing four imperatives, show how the church needs to live: Practise unity, stand with the oppressed, study God's Word, and obey Christ. This article addressed the realities of South Africa directly. It is important to see that the intimate connection between the gathering and liberating work of God in this article: Since the DRC family had become infected with racism to the extent that it consisted of four racially constituted churches, the (re) unification of the family could only happen by its liberation from the oppressive power of racism. Therefore, church unity in that context could never be an internal church issue, while poverty and unemployment were political and economic issues. Church unity was just as political as poverty was religious, due to the theological legitimation given to the apartheid system by white Reformed churches and theologians. That made the attempt to rescue the credibility of the Reformed tradition in the black community a daunting, yet urgent, task.

The evocative expression "busy standing where God stands" is perhaps the greatest gift that the BK Declaration has given to the Reformed tradition in South Africa and (through its later inclusion in the Belhar Confession) to the worldwide Reformed community. This is an enormously encouraging pastoral image: God standing by our side, with us, in our suffering and pain. At the same time, it is an enormously demanding image: Since we belong to God, we need to go and stand with others in their pain and suffering. The strange expression: "the church... must be busy standing..." shows that God's 'standing with' the unjustly treated does not mean passivity but a unique kind of activity and engagement: A deep identification and solidarity (being with people) that is not tempted into shallow acts of charity (doing for people). (c) How did the Declaration engage the 'fathers' of the Reformed (and broader Christian) tradition? There are many resonances between this article and classical Reformed praxis: The emphases on God's initiative in gathering the church, the assurance of belonging to God, the necessity of an intense study of Scripture, and the calling to civil disobedience, when faithfulness to the gospel demands it. The notions of salvation as liberation from oppressive powers and of standing with the oppressed have not been dominant themes in Reformed orthodoxy, and yet there were times when Reformed Christians, like many other Christians in history, lived as religious refugees and 'churches under the cross' - and when they experienced the gospel in precisely this way. One of the important contributions of the BK, and particularly of Boesak as early leader of the organisation, has been their ability to show that there were redeeming features in the Reformed tradition - even though it had been 'conceived and born in sin' like all other European theologies - which could be 'taken up' and reinterpreted to serve the cause of opposing racism, sexism and every other form of oppression.44 In the BK there was the sense that, in its better moments, the Reformed tradition did indeed articulate and practise the centrality of God's compassionate justice and the need to confront political authorities in God's name.45

What are the biblical allusions in this article? Numerous passages come to mind, but the most important are those referring to God as 'standing with' people in need. This is not a common way of speaking about God's presence, but Psalm 109:30-31 is a clear example: "With my mouth I will greatly extol the LORD; in the great throng of worshippers I will praise him. For he stands at the right hand of the needy, to save their lives from those who would condemn them".

The Psalm refers to an active standing of God at the right hand of the needy. It does not suggest the condescending sympathy of a passive bystander, but an active advocacy and solidarity with the needy, to assist them in their predicament. In the historical context of the Psalm, it referred to an advocate or spokesperson intervening in a court case to save a falsely accused person from an unfair judgment (Kraus, 1966:750; Vos, 2005:257). In Psalm 16:8 one finds the same image of God's presence 'at the right hand' of a believer, even though the verb 'stand' is not used:

I keep the LORD always before me;

because he is at my right hand, I shall not be moved.

A similar image is used in Psalm 12:5-8:

Because the poor are despoiled, because the needy groan, "I will now rise up", says the LORD; "I will place them in the safety for which they long...". You, O LORD, will protect us; you will guard us from this generation forever. On every side the wicked prowl, as vileness is exalted among humankind.

The LORD promises to arise, literally to 'stand up' (Hebrew aqum), to take up the battle on behalf of the poor and the needy who are being despoiled and exploited, to give them safety and protection from the wicked who are prowling to take advantage of them. This biblical image of God's active involvement in the lives of suffering people - God's mission of doing justice - is a powerful challenge to the church as it discerns where God is at work in the world to participate in that mission with God.

(a) How did the Declaration provide an apologia to the BK's critics? The catholic and inclusive emphasis on "we" as "part of the church of Christ in the world" would be reassuring to critics who were suspecting or accusing the BK of sectarian tendencies and of being a 'pressure group' with sectional political or personal agendas.46 Every reader knew, however, that the words "unflinchingly persevere for establishing God's justice" would not result in comfortable agreement with the authorities but in uncomfortable confrontation, as becomes clear in the following sentence. The BK hoped that all DRMC and DRCA members would agree with its principled stand against injustice, with all the risks and dangers involved, but the Declaration is a clear apologia that shows how that stand emerges from a genuine Christian (and Reformed) faith.

(b) In what sense was this 'reality-directed,' contextual and pastoral theological reflection? It addressed the context directly, as all black Christians in South Africa in 1979 knew the possible dire consequences of taking a prophetic public stand against the injustices of apartheid. Its call for persistent action in pursuit of 'God's justice' meant opposition to apartheid's unjust laws, which was an implicit call for civil disobedience, but not for violence. In that sense, its message was almost identical to Gerald Pillay's (1993) view in a paper entitled: 'On civil disobedience as Christian responsibility'. It reiterated the clauses in the BK Aims that called Reformed Christians "to take seriously the prophetic task of the church with regard to the oppressive structures and laws in our land" and "to promote evangelical liberation from unrighteousness, dehumanisation and lovelessness in church and state".

It was a pastoral statement since it radiated encouragement and comfort. The quote from Hebrews 13:5, the only explicit reference to Scripture in the Declaration, was no pious afterthought, but gave pastoral encouragement and empowerment to those who were willing to risk "greater obedience to Christ than to human governments, power or ideologies" (Article 3). In everyone's minds there would have been recent government actions, like the death in detention of Steve Biko, the banning of Black Consciousness organisations and community leaders (including Beyers Naudé, a BK member and close friend of the drafters of the Declaration), and the constant threat to the livelihood of outspoken DRCA and DRMC ministers.47

(c) How did the Declaration engage the 'fathers' of the Reformed (and broader Christian) tradition? The Declaration acknowledges that suffering, due to "conflict with human authorities", for speaking and acting prophetically has been an integral part of "the way of God's people throughout history". This 'prophetic catholicity' was explained by Loff (1979a:18), where he referred to the church struggle in Germany in the 1930s and the courageous witness of church leaders like Niemöller, Barth and the Pfarrernotbund against the Nazi authorities. In this way the Declaration created a deep sense of connection with the "crowd of witnesses" (Hebrews 12:1) in history who suffered for God's justice, in the firm belief that God would never leave or forsake them, as they hoped and worked for "the city that is to come" (Hebrews 13:14), the city with foundations, "whose architect and builder is God" (Hebrews 11:10).

5.4 Contextual understanding

In the foregoing sections much has already been said about how the BK Declaration understood the South African context at the time. Instead of repeating all that, it is only necessary to highlight some aspects of the BK's contextual understanding that have not yet surfaced explicitly.

One must reckon with the fact that 'confessional' documents by their very nature are generic, in the sense that they intend to be read and appreciated for a few years and that they therefore do not speak too explicitly about historical events. They try to find a middle path between 'universal' generalities and highly specific comments about contemporary events. This can be viewed as either a strength or a weakness, but it seems to be true of the BK Declaration, as it is true of the Barmen Declaration and the Belhar Confession, to mention two related documents. When the Declaration therefore speaks about 'victims of injustice', 'oppressive powers' and 'ideologies', it does not fill in the details due to the self-imposed restraint characteristic of the genre of a 'confessing' statement. It falls outside the scope of this essay to trace all the ways in which the BK as a theological movement or organisation filled in the meaning of these terms, but it will be an interesting and fruitful exercise, particularly if one works through all the BK's statements, publications and activities. The fact that the BK Declaration did not openly articulate all the cultural, political, economic and gender dimensions of the BK's praxis does not detract from its importance or value as a confessional statement. In fact, it ensured that the Declaration is still theologically relevant and evocative 38 years later.

5.5 Ecclesial scrutiny

As with contextual understanding, much of the Declaration's view on the church in South Africa has already been indicated, however a few pointers can be given for further investigation. The Declaration speaks of the church as 'a new people' who consist of 'men and women' whom God has 'liberated from oppressive powers' and who should live as 'the one undivided body of Christ' and as 'God's property', should 'stand where God stands' and 'constantly search after the truth of God's Word'. Each of these phrases implied a fundamental critique on the DRC family as it existed in 1979. Not much of the newness of the people gathered by God or the undivided body of Christ was visible in the racially constituted 'DRC family' at the time. Very few of the women whom God had (also) liberated from oppressive powers were able to play an active public role in the church. The DRC family seemed to 'belong' more to the ideology of apartheid or 'separate freedoms' than to Christ as its only Head. Instead of standing with communities threatened with forced removals or suffering due to race classification and labour discrimination, the congregations were 'playing it safe' and passing by 'on the other side'. Instead of constantly searching God's Word for the truth, too many ministers and members of the church remained trapped in the lie of apartheid's false promises. In its Declaration, the BK wished to call the DRC family out of this malaise to the risky journey of greater obedience to Christ than to 'human governments, power or ideologies'. The question is not whether they were successful in achieving that goal; the question is whether they were faithful in articulating the radical call of the gospel to participate in God's mission of establishing justice and making this world a home for people to live in.

5.6 Spirituality

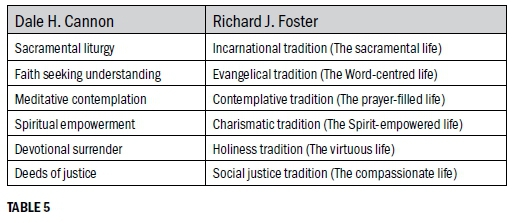

What was the spirituality that sustained, guided and empowered the BK, as revealed in its 1979 Declaration? Out of what kind of encounter with God did this praxis emerge? The sixfold typology of spiritualities developed by Cannon (1994) and Foster (1998) can be helpful to describe the spirituality integral to the BK Declaration (see Table 5).

The BK Declaration reveals a preference for the second (faith seeking understanding) and the last (deeds of justice) types of spirituality, but there is also an element of devotional surrender. Much more research of the BK's publications and activities is needed before one can make more definitive conclusions in this area. One of the criticisms levelled at the BK was that it was politicising the gospel, which is why Loff (1979b:14) concluded his explanation of the Declaration (after its release) as follows:

To the benevolent misinformed and the malevolent informed, we wish to say with our declaration that we are believers in Christ and that we deny categorically that we are a pressure group of whatever kind. We are not busy with politics but with theology, although theological activities need not necessarily be apolitical speculation (my translation).

As one of the drafters of the Declaration, Loff wanted to clarify that their motivation was not (party) political or 'ideological' but based on a deep sense of having been called by God to participate in God's mission of establishing justice for all.

5.7 Reflexivity

The final dimension of the praxis matrix asks the question whether there is evidence that the community under investigation learnt from their experiences, both negative and positive, and adjusted their approach in response. Another way of saying this is to ask whether the BK members experienced ongoing conversions on their journey. Since this study of the BK Declaration presents a 'snapshot' rather than a 'video' of the BK's activities, it does not give much evidence to answer this question, but the need identified by Loff for the BK to issue a statement of faith was indeed an act of reflexivity. It responded to negative perceptions about the BK and attempted to correct them. Although one could not call this a conversion on the part of the BK, it did represent 'learning from experience'.

The Declaration called members of the DRC family to reflexivity, to re-examine their lives and to commit themselves to an intense engagement with Scripture and a discovery of the nature of God as the one who seeks justice and who stands with the oppressed and exploited. It called BK members, who had earlier endorsed the BK Aims, to commit themselves to a journey of ongoing conversion towards an ever greater 'evangelical liberation' from oppressive powers and an ever-greater realisation of the undivided body of Christ, thereby giving a clear account of the hope that lives within them.

6. Conclusion

In my earlier article (Kritzinger 2010), I explored the influence that the BK Declaration had on the content of the Belhar Confession, however at the end of this essay, it seems justified to say that it played a more important role. It did not only influence the wording of Belhar; it actually prepared the ground and set the scene for the Belhar Confession by reading the signs of the times and discerning the urgency to clarify what the gospel ofJesus Christ is all about. One could see Loff's (1979b:14) argument for the Declaration as an excellent justification for the drafting of the Belhar Confession three years later:

Situations may arise where people or a church feel that the existing Confessions are inadequate. The demands of the time require a special emphasis on certain aspects of the faith. A new formulation of faith need not replace the existing ones. It also does not mean that the whole field needs to be covered (my translation).

With reference to the Barmen Declaration (1934), Loff (1979b:14) continued:

The old confession that Jesus is Lord needed to be formulated anew. It became necessary to say to the church and the government what it means to be a Christian. The lordship of the triune God should be pre-eminent (my translation).

Loff's implicit call for a new Reformed confession to clarify the meaning of the gospel in a country where the Reformed tradition was used to justify and legitimate racist oppression, can only be called prophetic. He sensed that the theological-political-spiritual crisis facing the Reformed tradition in South Africa would compel those within the Reformed tradition who truly cared for the credibility of the gospel in South Africa to 'raise the stakes' by formulating a confession of the Lordship of Christ against the distortion of the gospel. The BK Declaration was an important milestone on the road that led to the Belhar Confession, and it was perceptive of

Lukas Vischer to recognise its importance and to include it in his book on contemporary Reformed confessions (Vischer, 1982). Van Rooi (2008:178) may well be right in saying that the BK Theological Declaration was "without a doubt the most important document published by the BK".

7. Acknowledgements

I acknowledge the assistance of Mrs Tilly Loff and Mr Ivan Liedemann for information on the life of Dr Chris Loff and the helpful comments of Rev Cobus van Wyn-gaard on an earlier draft of the essay.

References

Aulén, G. 1931. Christus Victor: An historical study of the three main types of the idea of the atonement. AG Herbert (transl). London: SPCK. [ Links ]

Belydende Kring. 1979. Theological Declaration of the Broederkring of DR Churches. Dunamis, 2(4) & 3(1), 3. [ Links ]

Belydende Kring. 1981. Teologiese verklaring. Dunamis, 5(2), 15. [ Links ]

Belydende Kring. 1988. Statement. Dunamis, 1, 16-17. [ Links ]

Boesak, A.A. 1976. Farewell to innocence: A social-ethical study of Black Theology and Black Power. Johannesburg: Ravan Press. [ Links ]

Boesak, A.A. 1977. Editorial. Dunamis, 1(1), 2. [ Links ]

Boesak, A.A. 1984. Black and Reformed. Apartheid, liberation and the Calvinist tradition. Braamfontein: Skotaville Publishers. [ Links ]

Boesak, A.A. 2015. Interview with Allan Boesak. In M. Coetzee, R. Muller & L. Hansen (eds.), Cultivating seeds of hope. Conversations on the life of Beyers Naudé. Stellenbosch: SUN Media, 119-132. [ Links ]

Bosch, D.J. 1985. The fragmentation of Afrikanerdom and the Afrikaner churches. In C. Villa-Vicencio & J.W. de Gruchy (eds.), Resistance and hope. South African essays in honour of Beyers Naudé. Cape Town: David Philip. 61-73. [ Links ]

Britz, W.M. 1927. Kwaadstigters. In A.B. le Roux (ed.), Die Stofberg-gedenkskool (van die Ned. Geref. Kerk in SA.). Sy ideale en sy werk. Viljoensdrift: Stofberg-gedenkskool, 19-20. [ Links ]

Cannon, D.H. 1994. Different ways of Christian prayer, different ways of being Christian. Mid-stream, 33(3), 309-334. [ Links ]

Cloete, G.D & Smit D.J. 1984. A moment of truth. The confession of the Dutch Reformed Mission church. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Cochrane, J.R, de Gruchy, J.W. & Petersen R. 1991. In word and deed: Towards apractical theology for social transformation. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications. [ Links ]

De Gruchy, J.W & Villa-Vicencio, C. 1982. Apartheid is a heresy. Cape Town: David Philip. [ Links ]

De Gruchy, J.W. 1991. Liberating Reformed theology: A South African contribution to an ecumenical debate. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

De Jong, G.W. 1971. De theologie van Dr GC Berkouwer. Een strukturele analyse. Kampen: Kok. [ Links ]

Foster, R.J. 1998. Streams of living water: Celebrating the great traditions of Christian faith. New York: HarperCollins. [ Links ]

Govender, S.P. 1984. Unity and justice: The witness of the Belydende Kring. Braamfontein: Belydende Kring. [ Links ]

Gutierrez, G. 1973. A theology of liberation: History, politics and salvation. London: SCM Press. [ Links ]

Henriksson, L. 2010. A journey with a status confessionis Analysis of an apartheid related conflict between the Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa and the World Alliance of Reformed Churches, 1982-1998. Studia Missionalia Svecana CIX. Uppsala: Swedish Institute of Missionary Research. [ Links ]

Hofmeyr, Hoffie. (J.W.) & Stenhouse, J. 2018. Internationalising higher education: From South Africa to England via New Zealand. Essays in honour of Professor Gerald Pillay. Pretoria: Mediakor., 143-174. [ Links ]

Holland, J. & Henriot, P. 1983. Social analysis: Linkingfaith and justice. Maryknoll: Orbis. [ Links ]

König, A. 1980. Die heil - alles heel. Pretoria: NG Kerkboekhandel. [ Links ]

Kraus, H.J. 1966. Psalmen 2. Biblischer Kommentar Altes Testament XV/2. Neukirchen: Neu-kirchener Verlag. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, J.N.J. 1984. From Broederkring to Belydende Kring. What's in a name? In S.P. Govender (ed.), Unity and justice: The witness of the Belydende Kring. Braamfontein: Belydende Kring. 5-12. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, J.N.J. 2008. Starting with Stofberg: A brief survey of hundred years of missionary theological education in the DRC family, 1908-2008. In Acts of Synod. Fifth General Synod 2008. 29 September -5 October 2008. Hammanskraal: URCSA. 171-185. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, J.N.J. 2010. Celebrating communal authorship: The theological declaration of the Belydende Kring (1979) and the Belhar Confession. Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae, 36, 209-231. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, J.N.J. 2013. The struggle for justice in South Africa (1986-1990): The participation of the Dutch Reformed Mission Church and the Dutch Reformed Church in Africa. In M.A. Plaatjies-van Huffel & R. Vosloo (eds.), Reformed churches in South Africa in the struggle for justice: Remembering 1960-1990. Stellenbosch: SUN Press. 92-117. [ Links ]

Kritzinger J.N.J. 2015. Standing together for unity and justice. The relationship of the Bely-dende Kring to the Churches in Germany (1974-1994). In H. Lessing, T. Dedering, J. Kampmann & D. Smit (eds.), Contested relations: Protestantism between Southern Africa and Germany from the 1930s to the apartheid era. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications. 458-469. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, J.N.J. & Saayman, W. 2011. David]. Bosch: Prophetic integrity, cruciformpraxis. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications. [ Links ]

Loff, C.J.A. 1979a. Predikant en teologie. Dunamis, 2(4) & 3(1), 16-21. [ Links ]

Loff, C.J.A. 1979b. Kantaantekeninge by ons 'Teologiese Verklaring'. Dunamis, 3(2), 13-14. [ Links ]

Loff, C.J.A. 1998. Bevryding tot eenwording: Die Nederduitse Gerformeerde Sendingkerk in Suid-Afrika, 1881-1994. Kampen: Theologische Universiteit van de Gereformeerde Kerken in Nederland. [ Links ]

Meijers, E. 2008 Blanke broeders - zwarte vreemden: De Nederlandse Hervormde Kerk, de Gereformeerde Kerken in Nederland en de apartheid in Zuid-Afrika, 1948-1972. Kampen: PThU. [ Links ]

Mokgoebo, Z.E. 1984. Broederkring: A calling and struggle for prophetic witness within the Dutch Reformed Churches in South Africa. Masters dissertation, New Brunswick Theological Seminary. [ Links ]

Mouton, J. 2001. How to succeed in your Master's and Doctoral studies. A South African guide and resource book. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Mukuka, G.S. 2008. The other side of the story: The silent experience of the black clergy in the Catholic Church in South Africa (1898-1976). Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications. [ Links ]

Pelikan, J. 1988. The melody of theology: A philosophical dictionary. Cambridge, MS: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Pillay, G.J. 1993. On civil disobedience as Christian responsibility. In D.M Balia (ed.), Perspectives in theology and mission from South Africa: Signs of the times. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press. 41-61. [ Links ]

Pillay, G.J. 1994. Church and society: Some historical perceptions. In C.W. Du Toit (ed.), Socio-political changes and the challenge to Christianity in South Africa. Pretoria: University of South Africa. 19-33. [ Links ]

Smith, N.J. 2009. Die Afrikaner Broederbond: Belewinge van die binnekant. Pretoria: LAPA Uitgewers. [ Links ]

Van Oel, M. 2011. De wereld in huis: Buitenlandse theologiestudenten in Kampen, 19702011. Kampen: Protestantse Theologische Universiteit. [ Links ]

Van Rooi, L. 2008. To obey or disobey? The relationship between church and state during the years of apartheid: Historical lessons from the activities of the Belydende Kring (19741990). Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae, 34(1), 173-191. [ Links ]

Vischer, L. 1982. Reformed witness today: A collection of confessions and statements of faith issued by Reformed Churches. Bern: Evangelische Arbeitstelle Oekumene Schweiz. [ Links ]

Vos, C. 2005. The theopoetry of the Psalms. Pretoria: Protea Book House. [ Links ]

Wijsen, F., Henriot, P., & Mejia, R. 2005. The pastoral circle revisited: A critical quest for truth and transformation. Maryknoll: Orbis. [ Links ]

Wilkins, H., & Strydom, H. 1978. The super-Afrikaners: Inside the Afrikaner Broederbond. Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball. [ Links ]

1 An earlier version of this paper appeared in Hofmeyr and Stenhouse (2018), and it is published here with the permission of the editors.

2 Klippies Kritzinger is an emeritus professor of missiology at the University of South Africa and a research fellow in its Department of Christian Spirituality, Church History and Missiology. He can be contacted at kritzjnj@icon.co.za.

3 The Afrikaans term means 'Confessing Circle'. The original name of the movement was 'Predikante Broederkring van N.G. Kerke' but it came to be known simply as Die Broederkring, as a broederkring (literally 'circle of brothers') refers to a ministers' fraternal. Therefore, the original name meant 'Ministers' Fraternal of D.R. Churches'.

4 This two-pronged focus of the BK was clearly expressed in the title of the book published in 1984 to mark its 10th anniversary: Unity and justice. The witness of the Belydende Kring (Govender, 1984).

5 To save space, I refer to the BK Theological Declaration as 'the BK Declaration' or simply 'the Declaration'.

6 The Confession of Belhar was drafted in 1982 by the Dutch Reformed Mission church (DRMC) and formally approved by it as a confession (or doctrinal standard) in 1986 (Cloete & Smit, 1984).

7 In that article I hinted at the possibility of a paper like the present one: "It is not possible to analyse the BK Declaration in depth. That could be the theme of another article" (Kritzinger, 2010:222).

8 The term 'praxis' in this paper is not synonymous with practice or action; it refers to theory-laden action (or action-embedded theory) aimed at societal transformation. The interplay between theory and practice produces a complex configuration of factors, which requires an instrument like the 'praxis matrix' to explore adequately.

9 Christian faith is always embodied and performed by a specific faith community in a particular context. Not every performance of Christian faith is intentionally aimed at (some form of) societal transformation, but when it is, it can be called praxis (= transformative performance).

10 See Kritzinger and Saayman (2011), in which Willem Saayman and I used this matrix to analyse the mission praxis of David Bosch.

11 For this entire development, see Holland and Henriot (1983), Cochrane, de Gruchy and Petersen (1991) and Wijsen, Henriot and Mejia (2005).