Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Missionalia

On-line version ISSN 2312-878X

Print version ISSN 0256-9507

Missionalia (Online) vol.45 n.1 Pretoria 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.7834/45-1-90

ARTICLES

Reflection on glocal worship in missiology in the context of the marginalised, yet never silenced, black African worship music from missio Dei perspective

Aaron Takalani Muswubi1

ABSTRACT

This article reflects the glocal worship challenges in missiology in the context of the marginalised, yet never silenced, black African worship music. As a minister in the innercity of Hillbrow Johannesburg the researcher met and lived with many marginalised Black Africans. The concept, 'glocalisation' helped him to reflect more on the contestation between the official Western Psalters and hymnodies and the unofficial black African (free) worship songs. In the contestation the black African worship song are marginalised, yet they are not silenced. In this regard, the researcher became aware of the fact that the contestation is actually between the Western and African socio-historical settings or contexts of their respective worship song tunes and styles and hence not necessarily based on biblical principle. This finding pave the way toward the handling of the contestation and also towards addressing glocal worship in missiology as one of the Church's missional calling to the marginalised people today.

Key words: Marginalised, Black African worship music, Glocal worship, Missiology, Globalisation, Glocalisation and the missio Dei perspective.

1. Introduction

The researcher is working as a pastor in Good News Community Church and also in partnership with the Hillbrow Family of Churches since 2010. Hillbrow is one of the innercity in Johannesburg. It is a cheap and accessible, hence densely populated area with the neighbours, the homeless, the jobless, the victims of rape and of any form of abuses, any form of drugs and alcohol addicts, the emotionally confused and traumatized people, the poorest of the poor, the legal and illegal refugees etc. Mpe (2001) and Green (2015) among others give more details on the social dynamics of the innercity of Hillbrow. The masses of the residence are marginalised, yet are also part of what Nolan (1976:29) called Christ's favorites. The Good News Community Church (abbreviated as GNCC) in Braamfontein, in Johannesburg is a multi-cultural church. GNCC is part of the Greater Johannesburg Classis of the GKSA (Gereformeerde Kerk in Suid Africa). In GNCC, most church members come from many and varied ethnic groups with distinct cultural backgrounds and music styles. They worship together in the same worship service. These includes the English, Afrikaans, Venda, Tsonga, Sotho, Tswana, Pedi, Zulu, Shona, Chewa, Swahili, Congolese, Cameroonians and Sudanese. They worship together in the same morning worship service using both the Psalters and hymnals from Western origin and many free songs. The GNCC is part of the Hillbrow Family of Churches (abbreviated as HFC), a fraternal of Church leaders in the innercity of Hillbrow and around. As Saayman (2010:14, 15) described the missional calling of the local church, these local Churches felt, as their missional calling to work in this innercity which is at the same time a melting pot of both the postmodern North Atlantic culture and traditional African, Eastern and Latin-American cultures (cf. also Kirk 1997:7; McLaren 2007:44). They work with a view that the triune God is concerned about Hillbrow as he is concerned about the entire world from its creation to its recreation as His scope of activities as Wright (2006:63f) and Bosch (1991:391f) argued. It is from this perspective that these churches are attempting to sing the spectrum of worship songs in such a glocal context. It is a context where they act locally while thinking globally (Bosch, 1991:457). It is the context where the liturgical (leitourgia) or public worship service of God which is directed to all of the humanity as well as to the rest of creation is viewed as part of God-given comprehensive calling together with the kerygma [proclamation], diakonia [ministry of service] and koinonia [communion or fellowship] as articulated by Hoekendijk (Kritzinger et al. 1994:36). The main question which remains to be answered is the contestation debate between the official western Psalters and hymnodies which are regarded as official and central and the unofficial (free) songs which are regarded as unofficial and peripheral. There are lot of attempts in this regard. Liesch (1996) and Hawn (2003) and many practical theology scholars suggested the blending or convergence of the traditional and contemporary worship styles. Liesch (1996:25) suggested the ratio of 50/50 or 25/75 or 60/40 as a convergence ratio of the traditional and contemporary worship songs on the same Sunday morning service depending on the compositions of the people and the church's history and traditions. Hawn (2003:2, 6f) also suggested the movement beyond the dichotomy between the western hymnodies which are mostly dominant and authoritative in the morning worship services and the free songs which are used in the beginning, the end and outside of the morning worship services. In support of the suggestions, this article discusses firstly, the concept glocalisation, its use in the Japanese context and its application to some black African music genre; secondly, the Church's missional calling to address the glocal worship music from the missio Dei perspective which is a challenge in missiology today and then the conclusion.

2. Glocalisation - a new and slippery concept.

Glocalisation is a new phrase or 'slogan' of the 21st century which has been widely used since the late 1980s (Giulianotti, 2012:433). It is derived from a popular Japanese business strategic concept, called, 'dochakuka' which refers to the way of adapting farming techniques to local conditions. The concept appeared first in the late 1980s in the articles which appeared in the Harvard Business Review (Levitt, 1983:92f). It is intensified by the travel, trade, television and other technologies (satellite) and to a large extent, by the English language as a global langua franca (Scholte, 2000:48, 59; Hendriks, 2004:15). And hence people everywhere despite the limits of place, distance and borders are gradually sharing many and varied global products, services, values, practices, tastes et cetera. In the process, many academic disciplines and research fields attached different meanings to it, yet it is still a slippery concept to define. In this article there are at least two broad ways of defining glocalisation, namely, as a local-globalisation and as a global-localisation. These definitions are like identical twins, with distinct, yet overlapping focuses.

2.1 It is viewed as a global localisation

In this case glocalisation is viewed from global-intended brand point of view. The focus involves incorporating (adopting, adapting and adjusting) certain globally-intended brands, products and/or services into the local settings, accounting for interest, tastes and preference (Robertson, 1992:28, 173; Khondker, 2004:3). It is in this regard that in this article the Psalms, Hymns and Spiritual songs (cf. Col.3:16; Eph.5:19) are regarded as a globally-intended worship songs as there were meant to be sung in a multicultural Churches in Ephesus and Colossae as full range of worship songs (Detwiler, 2001:1; Dunn, 1996:236; Martin, 1982:51) and hence their incorporated (adopted, adapted and adjusted) into varied multicultural melodies and tunes suited for local settings, interest, tastes and preference is also implied.

2.2 It is viewed as a local globalisation

In this case glocalisation is viewed from local-intended brand point of view. The focus involves the spreading the locally-intended brands, products and/or services far beyond that locality into a global arena. It is a global expansion of the local ideas, practices and institutions or the de-territorialisation or trans-territorial of previously defined local boundaries (Robertson 1992:97-114). It is in this regard that this article acknowledge many and varied local-innovated folk song tunes/styles which spread far beyond their locality into a deterritorialised or trans-territorial global arena (Robertson 1992:97-114)

2.3 Its origin and usage in the Japanese context

The concept glocalization is traced from the Japanese term, 'dochakuka' which refers to the way of adapting farming techniques to local conditions. The Japanese build their economies by linking their traditional culture with some aspects of western culture. Some of their proverbs offers further insight on this, including, "Wakon kansai" (means, Japanese spirit, Chinese learning) and "Wakon yosai" (means, Japanese spirit, Western learning). They learn western ideas, technology and services and then incorporate (adopt, adapt and adjust) those globally-intended brands, products and/or services into the local setting, interest, tastes and preference (Khondker, 2004:3; Robertson, 1992:90). For instance, McDonald product has a global brand (Levitt, 1983:92- 102) together with local elements (to be part and parcel of local life) like McSpaghetti in Philippines, Maharaja Mac and Veggie McNuggets in India, a kind of shrimp burger, Teriyaki Burger in Japan / Malaysia and so on. (Fujino, 2010:174-175; Kotler, 2009:467f). In this way, two distinct, yet overlapping processes run concurrently, namely, that while the globally-intended brands, products and/or services are incorporated, adopted, adapted and adjusted into the local settings, accounting for interest, tastes and preference, their own local brand with core indigenized elements incorporated in the same global-intended also spread far beyond their locality and into a global arena. The Church in the Glocal South (Asia, Africa and Latin America) can learn from the Japanese model of glocalization especially as far as worship music and songs are concerned.

2.4 Its application possibilities in the way worship songs were handled by Martin Luther and John Calvin amongst other Reformers in the sixteen century and beyond

It should be clear that the Church music has been affected in every age by the prevailing worldview or spirit of that age as Johansson (1992:35) argued. Due to time and space of this article, the focus will be on Lutheran and Calvin among the 16th century reformers. Both Luther and Calvin valued at least five worship precepts: (1) that music is a gift from God next to theology (Gritters, 2008:83; Garside, 1979: 64); (2) that singing should be congregational (Garside, 1979:12); thirdly, that an understandable vernacular or language of ordinary people should be used in singing (Garside, 1979:11); (4) that the popular tunes or melodies which are familiar to the ordinary people should be used (Garside, 1979:11; Leaver, 2007:13; Westermeyer, 1998:148f); (5) that the congregation should be trained or equipped so as to sing well especially to sing vocally (cappella), chorally (in unison) and in the right melody (Garside, 1979:64; McKee, 2003:19-20; Gritters, 2008:83). These Reformers incorporate (adopted, adapted and adjusted) the global-intended Psalm, Hymns and Spiritual Songs are into their local settings by using folk tunes, for according to them, Church worship songs should be understandable to ordinary people (Frame, 1996:115).

2.4.1 The use of folk tunes by Luther, Calvin and also Totius (J.D. du Toit) among others

As a former Augustinian monk, Luther was familiar with ancient Greek music, Gregorian chants and other Roman Catholic tunes which were already familiar to the majority of the people in Germany (Rothra, 2009:4). Calvin also sought and used first rate melodies and tunes of his times with the help of a professional musician, Louis Bourgeois (Kirby, 1955:9). Calvin's Geneva Psalter was completed in 1562. Its tunes were once nick-named "Geneva Jigs", as they were regarded as simple, direct and popular tunes of the time. But the very tunes made the Genevan Psalter more strong and memorable style of the time and had an influence even beyond the Reformed Christian world (Kirby, 1955:7; Wilson-Dickson, 1992:66). As much as culture is inseparable to Church liturgy and music (Byars, 2002:17f; Kruger, 2007:651; Ludik, 2008:16; Strydom, 1994:52), J.D du Toit (Totius) also used the volk (hymn) tunes in versifying the Psalms into Afrikaans for the Afrikaans-speaking churches and the volk (Akrofi & Smit, 2007:181ff). The singing tunes of Psalm 38, 46, 48, 68 and 130 particularly evokes loyalty to the Bible and also patriotism to the Afrikaans nation's religion, history and culture (Akrofi & Smit, 2007:194). It is a challenge to avoid biases and prejudices in a multicultural worship services to the Church denominations whose members' ears are accustomed to the worship song tunes or melodies based on a homogeneous heritage (Solomon, 1992:2; Cart-wright, 1997:6f; Kirk, 1999:82f).

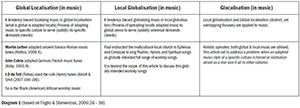

2.4.2 An application of two-ways approach of glocalisation in a multicultural worship service

According to Cartwright (1997:6-9) "....we can learn to read scripture together, but only if we began to recognize and expose the hidden histories that constitute our identities ....(with their) different kind of struggle with the Bible....in largely separate ways. " The same challenge was put differently by Kirk (1999:82-83) saying, "We are so immersed in our own culture that it is hard to see its defects or to see the strengths and goodness of other cultures. What we are familiar with is often taken as the standard for judging what others do. We do not see the subtle, and perhaps insidious, influence of culture on our beliefs and behaviour." In this article, the Psalms, Hymns and Spiritual songs (cf. Col.3:16; Eph.5:19) are regarded as a globally-intended worship songs as they were meant to be sung in a multicultural Churches in Ephesus and Colossae as full range of worship songs (Detwiler, 2001:1; Dunn, 1996:236; Martin, 1982:51). In the Diagram 1 below, it is indicated that, on the one hand, the globally-intended worship songs should be contextual-ised (cf. glocal localisation), that is they should be incorporated (adopted, adapted and adjusted) into varied multicultural melodies and tunes suited for local settings, interest, tastes and preference and on the other hand, they can be globalized (cf. local globalisation), that is, the locally-intended worship song styles can be spread globally to be exercised universally by other cultures. But this latter process is optional (not compulsory) that other cultural groups can use a locally intended worship style..

In this way, this article is attempting to address the problem of marginalised wo-ship music styles and tunes. It became clear that the concept glocalisation can be applied in the music context. In this article, the sixteen century reformers' setting of Martin Luther and John Calvin and that of the Afrikaans are used as an example of how globally-intended worship songs like Psalm, Hymns and Spiritual Songs were integrated and incorporated for the sake of the ordinary Church members by using tunes and melodies which are understandable or able to sing in their respective socio-historical settings /context. The problem is experienced when those locally intended worship song styles are formalized as criteria and/or standards for other cultural groups like the black (American) Africans who also have their own socio-historical settings or context as the basis of their melodies or tunes. They should also incorporate (adopted, adapted and adjusted) the Psalm, Hymns and Spiritual Songs as a general (globally-intended) framework using their own specific music styles which are understandable (able to sing) by ordinary Church members in their own socio-historical settings.

2.5 The marginalised, yet never silenced music: the Black American and the Black African music among others

The music that originated from the Black Americans slaves and also from the Black African apartheid victims were marginalised in the official Church decisions, yet never silenced in the local (black) Church worship settings.

2.5.1 The black-American Spirituals- an example of marginalised, but never silenced music

A lot has been written about the black American spirituals, which are the songs that originated by the slave from the mid-1700s (Wilson-Dickson, 1992:193). Philip B Blish (1838 - 1876) collected old and new hymns and tunes chosen for Gospel spreading from cradle to grave (i.e. from the Sunday school, youth, formation of robes choirs, recreation facilities for family activities, libraries, Publishing houses and seminaries etc (Geider, 2008:24f; Wilson-Dickson, 1992:188). The Spirituals were incorporated with other Euro-American music genre during the Great Awakening and other Euro-American revivals in the early 1800s and hence spread worldwide (Frame, 1996:116; Combee, 2011:314). These easy-to-pick, emotionally-charged songs/choruses with repeated short refrains were sung by both white and blacks while accompanied by hand-clapping and foot stamping. They are learned by simply imitating the melody, rhythm, and words, and performance in and outside the church and hence passed down through religious ceremonies, birthday etc. (Wilson-Dickson, 1992:188). They were marginalized in the official Church decisions, yet never silenced in and outside their local Church worship settings.

2.5.2 The Hillbrow innercity as the melting pots of glocal music genre

According to Mpe (2001:3), "By 1990', Hillbrow was considered either as a sophisticated melting point of cultures, class and ethnicity or decaying city scape of violent crime, drugs, prostitutions and AIDS". Griffiths and Clay, (1982:9), also argued that, "the often-cited high crime rate in Hillbrow must be seen in relation to the high population density, and is not the highest in the country.. ..because more people are crowded into Hillbrow than anywhere else in South Africa, there's naturally more of everything else. Hillbrow itself is never static. The first place in South Africa to reflect the changes in society, to follow the trends, it's something like a barometer of what is new in the young, free world and it reflects all the economic ups and downs of South African society - of which, for all its differences, it is very much a part". Hillbrow's high population density is due to people coming from anywhere else in and outside South Africa and hence this innercity reflects what is trending in and outside South African society (Green, 2005:3). This innercity absorbs, incorporate and creatively remix the black (American) African and Euro-North-Atlantic music elements into the glocal music genre (local-global music remixes) (Muller, 2004:7). For example the tap dancing and male dominant a capella group called isicathamiya {from the verb cathama meaning standing on tip-toe (Muller, 2004:6)}. Such music genre incorporated Euro-North American music elements like gumboots, guitar and four-part harmony hymns (Coplan, 1985:72f). In this context, even worship music is also a music of encounters, which is fluid, in flux and open to new possibilities (Muller, 2004:5; Stewart, 2000:2f). Due to the trade, travel and technology such a glocal music spread worldwide (Muller, 2004:8f).

2.5.3 The black-African Spirituals- an example of marginalised, but never silenced music

Choral music combines Euro-American classical and popular songs and African traditional songs (Coplan, 1985:267). The western tonic solfa notation system (four part harmony) was introduced and learned at schools by school children and at churches by church members as they were regarded as official standard worship music styles intended for both civilisation (secular) and for conversion (sacred) of the indigenous inhabitants (Muller, 2004:2f; Stewart, 2000:2f). Due to African vocal tone, the tonic solfa notation was adopted and adapted easily and hence spread widely throughout South Africa especially in the semi and urban areas by the emerging African middle class and the educated elites (Agawu, 2003:8; Stewart, 2000:3f; Blacking 1982:297). From the more hymn-dominant style, they were also developed and popularized in the choir concerts, Eisteddfods and other Music Festivals and Choir competitions since the 1930s (Coplan, 1985:72; Stewart, 2003:3f). Even when by the 1950s, the National Party government eradicated the missionary and hymn (Choral) singing influence in the schools. The Choral music incorporated the Choruses and other gospel music and since the 1980s they were performed with vocal inflection and independence, and solo performance with group support and bodily movement using an informal, free flowing robe-like African choir uniform and hence replace the more formal, tighter fitting and less-flexible European buttoned blouses and skirts choirs uniform (Muller, 2004:5) and were performed for commercial interests (James, 1999:155). The melody lines (major and minor) accommodate improvised and overlapping parallel melodies and polyphonic tonalities and other accompaniments like dancing, gestures and movements which are intrinsically part of music [learned by heart or by rote] (Muller, 2004:2f; Coplan, 1985:28f;117f).

2.5.4 The 'suspected' negative effects of Black (American) African music on people

It is noted in this article that music in general has both the constructive and destructive effects on the people including the marginalised people and hence Plato, Augustine and Calvin among others, warn us about the negative effect of music and it is not necessary to repeat them in this study (cf. Plato's Republic, Book 3; Augustine's confession, X.33; Calvin's preface to the Psalter by Oliver, 1965:158). But the negative effects of music influenced the decisions taken as reasons against the marginalized Black American/African worship music without regarding their settings, but only the specific western socio-historical settings of the western Psalm &/or Hymnbooks (cf. the Synod of Dordtrecht, 1618-19, Article 69; Westminster Confession of faith, 21.1; Totius's Collected Works Part 3:369, 383 & 432; GKSA Synod, 2009:741.1.4.3.2; Spoelstra, 1963:141; 1989:72f; Hofmeyr and Pillay, 1994:114, 115).

2.5.5 The 'acknowledged' positive effects of Black (American) African music on people

The multi-cultural worship service in Hillbrow Family of Churches incorporates Western and African worship songs in their morning worship services including choruses especially in the beginning, the end and outside of morning worship services, for instance, in the evening church service, cell-groups, Sunday school and youth programs, weddings, funerals, revival, outreaches, praise-and-worship, and comfort-visits meetings (Walker 1974:109; Harris 1983:202; Gifford, 1998:341; Calitz (2011:246). As Psalms, Black Worship music serves as a medium and instrument in expressing, reflecting, interpreting and articulating the way or essence of life (Merriam, 1982:69, 140-141; Schmidhofer, 1998:594). Worship music is the voice for God's people, which mirrors the culture and worldviews of society. It reveals, reflects and expresses thoughts and emotions, and shares important issues and themes. It is a platform for voicing criticism, commendation, reflection, questioning, rebellion and cry out for the answers God provides (Solomon, 1992:1). In the Black African context, music and life go together. It is not only present in almost each fibre of life, but it is also an integral part of African's daily personal and communal life (Tracey, 1986:30). To Roper (1975:310) in the Indian context for example, "it is impossible to divorce Indian music from the whole structure of Indian culture and philosophy with which it is interwoven in a number of ways." From the moment of birth/childhood African music is learned and always invites everyone to participate in the wholeness, togetherness and all aspects of Ubuntu life (an inseparable and integrated sacred and secular life which includes the socio-cultural and political activities (Bebey, 1975:8f; Chernoff, 1979:23; Nketia, 1974:22).

3. A missional call to the marginalised in the 21st century

In the Black African context, including the marginalised Hillbrow (innercity) people, music and life go together (Tracey, 1986:30). In that context the Hillbrow Family of Church experience their worship music in many and varied ways including bringing together (1) church life and everyday life, as they are sung everywhere (not only in church); (2) many people of disparate age (young and old) and, status (high, middle and low class), since they are accessible to and can be sung by everyone; and (3) various denominations (traditional and contemporary) churches, because they articulate God's attributes and deeds. Black African worship music's basic characteristics include (1) the call-and-response style whereby an opening line is usually led by soloist (group, choir or chorus leader), before the singers join in the singing, after which there is a group response, where the leader and groups' lines overlap, because as the group continuously follows in response, the leader continuously enters to take a lead; (2) they are repeated over and over again in a cyclical structure, for comprehension and internalisation purposes; (3) their pitch is relative to the skills and creativity of the singers and of the instrumentalist and hence does not depend on one universal and fixed pitch, but utilises relative pitch with complex and non-lineal rhythm or polymetric, polyrhythmic or cross-rhythmic interplay and a wide-spectrum of sound, tuning and melody, which depend on the speech tone, pronunciation, accentuation and rhythm of an African language; Last, but not the least, it is an accompanied music which involves instruments as communicative tool, which stimulate such individual and corporative expressive body movements like clapping, trapping and dancing (not arm and/or leg-crossing).

3.1 Jesus' word/manifesto in Luke 4:18f as part of missio Dei specifically to the marginalised

The question of the church's missional identity was transmitted from Leslie Newbi-gin in 1978 in England to the USA missiologist scholars from 1998 (Gelder, 2008:1, 3). Gelder, 2008:120-124) and Jeong (2007:7, 13-15) using the book of Luke and Acts to indicate that through the empowering work of the Holy Spirit, God used human weakness to perform His mission and Jesus's words in Luke 4:18f confirmed His association with the poor and the marginalised (Luke 5:27f; 7:31f; 15:1f; 19:1f). In this regard, Roxburgh and Romanuk (2006:15-18) have argued that missional leaders should lead the Church in Trinitarian mission destined to reach the least expected people, places and times based on incarnation principle. According to van Niekerk (2014:2), unlike Hoekendijk's method of mission, which did not, and does not challenge the political order of the day, Newbigin emphasised that the early church presented itself to address the real questions of people's lives such as poverty, violence and corruption amongst others (Newbigin 1986:99-100). Under the title, 'The new global mission: The gospel from everywhere to everyone', Samuel Escobar (2003:78) has argued that since there are few books on the prophets, healings, spiritism, exorcism and spiritual powers, "missionaries today are being driven to restudy the NT teaching about religiosity as well as about the presence and power of the Holy Spirit. Communication technology and techniques as well as an intellectual reasonable faith are not enough." In this regard, Chester and Timmis (2011:31) have argued also that living at the margins in a post-Christendom context means that, "we must think of church as a community of people who share life, ordinary life - everyday church with an everyday mission." Due to the church's nature - being from, but not of, yet called in the world - she is treated as a stranger in a secularised world, and hence, the Church as an everyday church and as a community of people should see it as an opportunity to operate also on the margins of society and hence share life, ordinary life in every moment of the day (24/7). It is an inevitable missional calling pointed out by many and varied mission scholars and organizations, including the ones mentioned below.

3.1.1 In the Accra Declaration of 2004.

Given the socio-economic and ecological injustice, the General Council of the World Alliance of Reformed Churches (WARC) made a declaration that, "God calls the church to follow (Him).... among other things, that the church must witness against and strive against any form of injustice.... (by) powerful and privileged people who selfishly seek their own interests and thus control and harm others" (cf. WARC, Article 14 to 36 in particular). According to Boesak, Weusmann and Amjad-Ali, (2010:80 - 81), it is a call upon the Church worldwide to work together towards unity and fullness of life for all including the poor, the vulnerable, the marginalised.

3.1.2 In the 2010 Edinburg centenary symposium

On the 14th and 15th of April 2010, the Norwegian Lutheran Mission Organisation hosted a symposium in Edinburg in memory of the 1910 Edinburgh Missionary Conference. The 2010 Edinburgh centenary confirmed the radical shift from 1910 to 2010 from the Church as a center of mission (i.e. doing mission) to Triune God as the center of mission (i.e. being missional) (Guder, 2000:53-55). It is in this context that the local Church is viewed as a glocal church and hence they should be involved in God's mission both locally and globally (Berentsen 2011:69)

3.1.3 In the (WCC) in 2012 statement

The World Council of Churches (WCC) adopted a document, entitled, "Together towards Life in changing landscape" accepting that the second and third world Church living in marginalised contexts should take the lead in God's mission as main agents cooperators or stakeholders of the mission in the margins of society, a mission which is integrally connected with social justice. Conn (1984:211f) already wrote about the shift in the Christian axis from the North to the South, the new center of ecclesiastical gravity and vitality, and the importance in church growth and theological construction. According to Van Engen (1991:193), in Asia, Africa and Latin America the Church is growing, yet operating "under tremendous pressure from other religions, severe restrictions on their evangelistic activities, and radical shortages of personnel, materials and finances [...] and dealt with new religious movements and the prophets, healings, spiritism, exorcism and spiritual powers." In order to address worship songs in a multi-cultural socio-historical seetings or practical situation it is important to view the context from the missio-Dei perspective as indicated in Diagram 1 below.

3.2 From missio Dei perspective

3.2.1 The reflection on the formation of human doxology is important in handling worship wars

As already indicated above (cf. 2.4.1 above), one of the five precepts for worship which the 16th century reformers, included Martin Luther and John Calvin was to value music is a gift from God next to theology (Gritters, 2008:83; Garside, 1979:

64). It is from this basis that music should be understood, especially when the formation, deformation and reformation missio Dei framework is taken into consideration as Diagram 2 below illustrated. This missio Dei framework is important in handling worship music disputes in the multi-cultural worship context. It is briefly elaborated below.

3.2.2 Basic point: any human being including the marginalised one is made after God's image

God made each human being after His image (eikon in Greek) (Gen.1:27). Wright, (2007:421) explained an image in two ways, namely (1) adjective explanation of an image focusing on the qualities that one possesses such as wisdom, power, goodness, gentleness (i.e what the person does-Ps.93, 145) and (2) an adverbial explanation of an image focusing on one's essence or core of being (i.e.who the person is (cf. Lightfoot 1892:144-48). Both explanations define God's image and are intertwined and bound together so that who the person is and what he or she does defines him or her as an image of God and can neither be separated from nor supplemented to each other. Each person has a creation right and capacity to be addressable by and accountable to God and is aware of God's communication (Wright, 2007:421, 422).

3.2.3 God in Christ deserves human doxology using the heart-felt worship music and songs

God made human being for the very reason to increase, inhabit, rule, cultivate and care for creation (Gen.1:26, 28; 2:15; Ps.8:6-9; cf. also Van der Walt, 1994:165,178-179; De Bruyn, 2000:55-58). He called and summoned all people groups (Ps.117:1; 104:10, 21; 148 & 150:6) with one ultimate goal (Ps.67; 86:9; 148:11f) that He alone will be glorified, worshiped, admired, marveled, praised, enjoyed et cetera (Ps.96:10-13; 98:7-9). It is what God Himself desired, expected, predicted and deserves from the beginning (Ps.22:27f; 46:10; 66:4; 56:9). According to Begbie, (1991:177f) as voices and priests of creation all human beings are secretaries of praise for the rest of creation, for in humanity inarticulate, yet never silent creation becomes articulate.

Music should take control of the inner and deepest core of one's religious life which relates to God (Prv 17:22; 23:7; Hos 7:11; Jer 17:9; 23:20; cf. also Heuvel, 1999:5). The heart-felt music is and should be viewed holistically as it involves, (1) the mind (the heart thinks, understands and believes what is being sung - 1 Cor 14:15f; Mt 9:4; 13:15; Rom 10:10; cf. also Frame, 1996:116f); (2) the emotions (the heart loves and desires, and rejoices in, singing to and for the Lord - Rom 10:1; Mt 12:30; Prv 3:5; Jn 16:22); (3) the will (the heart obeys a set of purposeful plan of what one sings (Prv19:21; 2 Cor 9:7; Rom 6:17); (4) the conscience (the heart is conscious of sinful tendencies in human nature in singing - 1 John 3:2021). Joyful, exuberant and heartfelt singing is one of the evidences that the church is Spirit-filled (Stott, 2007; MacArthur, 1986: 256) which is distinct from a skin-deep impersonal one (Ouweneel, 2009:32f)

3.2.4 Critical point: the deformation of human doxology and the misdirection of worship music

There are many ways that the fall of humanity into sin misdirected human doxology (praise and worship) including the Plato's tripartite schema and dualistic teaching. It is so powerful that it separates and distorts the biblical view about the nature and structure of the cosmos, humans and music and hence depicts anything related to the body and its emotions including musical rhythms, expressions and instruments as bad, or evil (cf. Diagram 3 below; cf. also Hodges, 2010:4; Edgar, 2003:82).

Indeed, music's associated with immorality and with pagan worship (that is used to invite gods for the worship and expel demons) is part of the deformation and the tempering effects of music (Andrews, 1992:31; Solomon, 1992:1; Chupungo, 1994:105; Fourie, 2000:112). But is misleading to view the human body and music (including music instruments like drum) and all that is associated with emotional expressions and elaborations as intrinsically and inherently bad or inferior or evil (Wilson-Dickson, 1992:23). Due to sin, the human body and music (including music instruments like drums are misdirected and hence confirm that the fall of Adam and Eve into sin defiled, distorted and corrupted the view of the Cosmos including human being as an image and how he or she communicate with God including through music. But the good news is that the intrinsic and inherent values of the Cosmos including human being as an image and how he or she communicate with God including through music remain intact (it is neither eradicated, nor destroyed) by sin. In Christ they are and should be restored, reinstated and redeemed (Gen.9:6; James 3:9; 1 Cor.117; cf. also Canons of Dordt, ch.3 / 4 Article 4). The redemption process, which was anticipated in the Old Testament, was fulfilled in Christ, and the Great Commission is given to the Church to bring Christ's redemption to humanity and to the rest of creation (cf. Lightfoot 1892:143f). It is unfortunate that that Plato single out the mind (reason) as he claims that the proper tune and melody purifies or elevates the mind to pursue the invisible and speculative world of form, beauty, harmony and order (Hodges, 2010:3-4) on the expense of other music expressions and rhythm mixing as practiced by non-western who are viewed as lower and inferior in a scale of cultural and religious development, including their inherently bad or evil music (cf. Conn, 1984:35, 55, 85; Fowler, 1995:20f).

3.2.5 Reformation (transformation) addresses the completed, yet unfolding creation of sound

Worship songs and music is and should be understood as part of God-given cultural mandate. The sound, its waves, properties, human larynx, wood, metal, reed et cetera lay vibrant to be unfolded, developed and , shaped into (worship) songs and music (Eph.5:19; Col.3:16). In this regard 'making disciples' and 'making music' are complementary mandates which need many and varied gifts to fulfill and God called and enabled specific people fulfill them (Edgar, 2003:102f; Rothra, 2009:1). It became clear in this article that as part of God-given cultural mandate worship songs and music is and should be understood as God's instrument in the redemption and commission process by not only making, but transforming music as a complementary mandates to that of 'making disciples' (cf. Mtt. 28:181). Making disciples need many and varied gifts including the gifts of making and transforming music so as to fulfill the mandate. Due to limited space and time this fact cannot be elaborated further and to get more detail on it, Edgar, (2003:102ff) and Rothra, (2009:1) among others are more helpful.

3.2.6 Towards the fullness of life through a holistic glocal worship

Christ brings salvation as an inner transformation of the whole person and which affect every area and aspect of one's life including socio-political and economic life. Diagram 2 above which indicates the metamorphosis process is used with its limitations to explain the transformation process (Guroian, 1997:377; Brown, 2011:17). This article argues that the Church is called to bring transformative gospel and to safe guard the integrity of the Gospel which point to the fullness of life. According to Fowler (1995:153), the integrity of the gospel is maintained when both the focus and the scope of the gospel is preserved and proclaimed. The focus of the Gospel is in the person's regeneration by God's grace and in his or her on-going personal relationship with God nurtured by prayers, reflections, bible studies et cetera. The scope of the Gospel on the other hand, is as broad as human life. Christ brings salvation to the whole person and the scope of such salvation pertains to every area and aspect of his or her own life including the socio-political and economic life. The Hillbrow Family of Churches felt, as their missional calling to work in and around the innercity of Hillbrow and around. It is a melting pot of the spectrum of the worship music and songs. in a local and yet global context. These local Churches use their God-given calling, a liturgical (leitourgia) calling, the public worship service of God to humanity as well as to the rest of creation as part of their God-given comprehensive calling together with the kerygma [proclamation], diakonia [ministry of service] and koinonia [communion or fellowship] as articulated by Hoekendijk (Kritzinger et al. 1994:36).

The Church worship music has been affected in every age by the prevailing worldview or spirit of that age (Johansson, (1992:35). The five precepts for worship music applied by the 16th century Reformers (including Luther and Calvin) and J.D. du Toit amongst others as a standard criteria to guide and direct their incorporation (adoption, adaptation and adjustments) of the folk (hymn) melodies and tunes into the global-intended Psalm, Hymns and Spiritual Songs will still be used as a common practices in the local Churches in and around Hillbrow, namely: firstly, that music is a gift from God next to theology (Gritters, 2008:83; Garside, 1979: 64); secondly, that singing should be congregational (Garside, 1979:12); thirdly, that an understandable language/vernacular of ordinary people should be used in singing (Garside, 1979:11); fourthly that the popular melodies/ tunes familiar to the ordinary people should be used (Leaver, 2007:13; Westermeyer, 1998:148, 149); fifthly that the congregation should be trained/equipped so as to sing well especially to sing vocally (cappella), chorally (in unison) and in the right melody (Garside, 1979:64; McKee, 2003:19f; Gritters, 2008:83). In this regard this article the incorporation (adoption, adaptation and adjustment) of the ordinary melodies and tunes into the global-intended Psalm, Hymns and Spiritual Songs is an important contextualisation of the Gospel message to the local settings so that singing is clear and understandable to the ordinary people and also to encourage the congregational participation in singing vernacular songs (Frame, 1996:115). The Hillbrow Family of Churches believe in what Gisbertus Voetius (1589-1676), formulated as the three aims of mission, namely the conversion (conversio gentium); church planting (plantatio ecclesiae); honouring God (gloria Dei) (Verkuyl, 1981:38; Kritzinger, Meiring & Saayman, 1994:36). As the local churches in the Hillbrow innercity, we exist, firstly to glorify God as the first and the ultimate goal (cf. Piper, 2010:232; the Heidelberg Catechism. Lord's Day 1, Question.1) and secondly to proclaim (Hebrew word basar equivalent to euangelizomai "to bring good news) and to make declaration (cf. exangello in LXX version of Psalm 9:14) of God's character and conduct also through their doxological songs (Kaiser Jr., 2000:34; Wright, 2010:246) and thirdly so that through such act the community of people is gathered in Christ and through His Spirit so as to experience the same transformation of the whole person and the fullness of life (cf. Wright, 2010:250). The fullness of life is well explained in Greek language. Unlike English, the Greek language has three different words for life, Firstly, there is bios  from which English word biology is derived, refers primarily to physical life (Luke 8:14); secondly the psuche

from which English word biology is derived, refers primarily to physical life (Luke 8:14); secondly the psuche  )from which the English word psychology is derived refers to psychological (behavioural) life (mind, emotions and will). The third Greek word for life is zoe

)from which the English word psychology is derived refers to psychological (behavioural) life (mind, emotions and will). The third Greek word for life is zoe  The English name 'zoology' for 'animal life' is the result of a mistranslation of this word, where-, in Greek it refers to the life that belongs to God that becomes ours when we cross the doorway of Christ and hence enters into a relationship with God (cf. James A Folwler (1998:11f.).

The English name 'zoology' for 'animal life' is the result of a mistranslation of this word, where-, in Greek it refers to the life that belongs to God that becomes ours when we cross the doorway of Christ and hence enters into a relationship with God (cf. James A Folwler (1998:11f.).

4. Conclusion

In this article, given the missio Dei framework, there are two ways of applying glo-calisation so as to handle the worship music styles and/or tunes in the multi-cultural worship service context. On the one hand, it should be acknowledged that there are globally-intended Psalms, Hymns and spiritual songs as Paul mentioned in Colossians 3:16 and Ephesians 5:19 as a general worship song framework which are and should be contextualized to suit many and varied local Church settings, interest, tastes and preference (Robertson, 1992:28f; Khondker, 2004:3). On the other hand, it should be acknowledged that since there are and should be many and varied local Church innovated folk song tunes/styles which are equally important and hence can and should likely spread far beyond their locality into a deterritorialised or trans-territorial global arena, they should not necessarily be institutionalized as the one-size-fit all, though they can inspire others and hence can be borrowed in composing and compiling the 21st century worship songs and music and beyond.

It is understandable that there was, is and will be a strong conviction that 'the well-established' worship style should remain in the centre and the host cultures' worship music style should be marginalised and remain in the periphery, if not be done away with altogether (Hawn, 2003:2, 6, 13). But the history taught us that the dichotomy debate regarding which worship style is central and which ones are periphery is no longer sustainable in multi-cultural church context both locally and globally (Hawn, 2003:2, 6, 13) as it just portray the mono-cultural ethnocentric worship style regarding the music, rituals and symbols as indicated in the historical development of the Church in many and varied context including the Jewish, Graeco-Roman and Western Europe/North American Church context as indicated in Diagram 4 below. Hence to ask Black Africans to sing Western tunes/ melodies is to be countercultural. Africans have an entirely different tonality that overlaps in different ways with western tonality (asking it is kind of like trying to pound a square peg into a circular hole). If you try hard enough, you can make it work, but it is abrasive to the Bantu ear.

In the Diagram 4 it is indicated the ethnocentric conviction of the varied well-established Churches' worship style throughout the centuries with a continuous dichotomy debate regarding their conviction that they should remain in the centre and their respective host cultures' worship music style should be marginalised and remain in the periphery, if not be done away with altogether. There are many and varied well-established Churches that can be used as an example, but the three are used in a general way in Diagram 3 to indicate that (1) when the gospel was well-established in the Jewish-dominant Church, they viewed their worship styles as superior towards their Gentiles Graeco-Roman converts, (2) likewise when the gospel was well-established in the Graeco-Romans Church, they viewed themselves as superior to their so-called inferior "Barbarian" European converts; in the same way, it can be read (3) when the gospel was well- established in the European-and North-American Churches, they viewed and still, in some, if not most case viewed themselves as superior to their so-called inferior "Heathen" second and third World converts.

4.1 Summary

In this way, this article is attempting to address the problem of marginalised woship music styles and tunes. It became clear that the concept glocalisation can be applied in the music context. In this article, the sixteen century reformers' setting of Martin Luther and John Calvin and that of the Afrikaans are used as an example of how globally-intended worship songs like Psalms, Hymns and Spiritual Songs were integrated and incorporated for the sake of the ordinary Church members by using tunes and melodies which are understandable or able to sing in their respective socio-historical settings /context. The problem is experienced when those locally intended worship song styles are formalized as criteria and/or standards for other cultural groups like the black (American) Africans who also have their own socio-historical settings or context as the basis of their melodies or tunes. In this article, a strong conviction which the established churches have on their worship styles that they should remain in the centre and the host cultures' worship music style that they should be marginalised and remain in the periphery, if not be done away with altogether (Hawn, 2003:2, 6, 13) is no longer sustainable in multi-cultural church context both locally and globally as it became clear in history that it portrayed the mono-cultural ethnocentric worship music style of the Established Churches which was and is still forced on their host Churches. Indeed any local-innovated folk song tunes/styles are by nature of God's cultural mandate is and should be viewed as important optional worship song styles which can spread far beyond their locality into a global arena and hence in that way they can be borrowed in composing and compiling the 21st century worship songs and music as it was and is still the case in most established denominations including most local churches that form the Hillbrow Family of Churches. Therefore both local-innovated worship song tunes/ styles are and should be equally used.

4.2 Recommendations

Due to space and time in this article there are issues which need further clarity as far as this article is concerned, including firstly, the view that the Psalms, Hymns and spiritual songs (Col.3:16; Eph.5:19) are regarded as a globally-intended worship songs as there were meant to be sung in a multicultural Churches in Ephesus and Colossae as full range of worship songs (Detwiler, 2001:1; Dunn, 1996:236; Mar-

tin, 1982:51); secondly the fact that Black Africans music and songs have an entirely different tonality that overlaps in different ways with western tonality (asking it is kind of like trying to pound a square peg into a circular hole); lastly, but not the least the suggestions put forward by Liesch (1996:25) and many practical theology scholars of the blending or converging the traditional and contemporary worship styles in a ratio of 50/50 or 25/75 or 60/40 as a convergence ratio of the traditional and contemporary worship songs on the same Sunday morning service depending on the compositions of the people and the church's history and traditions.

Bibliography

Agawu, K. 2003. Representing African Music: PostcolonialNotes, Queries, Positions. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Augustine of Hippo, 2008. Confessions, Chadwick, Henry transl. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Anderson, J. 2007. Paradox in Christian theology - an analysis of its presence, character and epistemic status. Waynesboro, Georgia, USA: Paternoster. [ Links ]

Andrews, T. 1992. Sacred sounds: transformation through music and word. Saint Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications. [ Links ]

Balia, D. & Kim, K. (eds.) 2010. Edinburgh 2010. Volume II, Witnessing to Christ today, Oxford. Regnum Books International. [ Links ]

Begbie, J.S. 1991. Voicing creation's praise: towards a theology of the arts. Edinburgh: T & T Clark. [ Links ]

Benedict XVI, 2009. Caritas in veritate, Encyclical letter of the Supreme Pontiff Benedict xvi, Libreria Editrice Vaticana. [ Links ]

Bernstein, A. 2002. Editor of Johannesburg-African's world city. Johannesburg: The center for development and enterprise. [ Links ]

Blacking, John. 1955. "Some Notes on a Theory of African Rhythm Advanced by Erich von Hornbostel." African Music Society Journal Vol. 1, no. 2: 12-20. [ Links ]

Bonhoeffer, D. 1970. Psalms: The prayer book of the Bible. Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House [ Links ]

Bosch, D.J. 1991. Transforming mission: paradigm shifts in theology of mission. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

Brightman, F.E. 1896. Liturgies, Eastern and Western, Vol.I, Introduction, xvii-xxix. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [ Links ]

Brown, T.M. 2011. Motherhood, the metamorphosis: a spiritual transformation for women and men. s.l.: Marie Brown. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, W. 1995. The psalms and the life of faith. MN: Augsburg Fortress [ Links ]

Burge, D., 1966. Perfect Pitch: Color hearing for expanded musical awareness. Fairfield, IA: American educational music publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Burgess, H. 1853. Select Metrical Hymns and Homilies of Ephraem Syrus, London: Blackader. [ Links ]

Byars, R. P. 2002. The future of protestant worship - beyond the worship wars. Westminster: John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Calitz, C.J. 2011. The free song (hymn) as a means of expression of the spirituality of the local congregation with specific focus on the situation of the Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa, (PhD.Thesis). Pretoria: University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Calvin, J. 1960. Institutes of the Christian Religion, Battles trans. Philadelphia: Westminster Press. [ Links ]

Chernoff, J.M. 1979. African Rhythm and African Sensibility: Aesthetic and Social Action in African Musical Idioms. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Chupungco, A.J. 1992. Liturgical inculturation: sacramental, religiosity and catechesis. Collegeville, MI.: The Liturgical Press [ Links ]

Conn, H.M, 1984. Eternal word and changing worlds. Theology, Anthropology, and Mission in Trialogue. New Jersey: P & R Publishing. [ Links ]

Coplan, D. 1985. In Township Tonight. New York: Longmans Group Limited. [ Links ]

Davis, K.L. 2003. Building a biblical theology of Ethnicity for Global mission. The Journal of ministry and theology (91 - 126) Baptist Bible Seminary. [ Links ]

De Bruyn, P.J. 2000. Ethical perspectives. Translated by D. Kempff. Pochefstroom: PU for CHO. [ Links ]

Delling, G, 1962. Worship in the New Testament, New York: ET, Darton, Longman & Todd. [ Links ]

Demol, K.A. 1999. How should Christians think about music? Pochefstroom: PU for CHO. [ Links ]

Edgar, W. 1986. Taking note of music. Wallingford, United Kingdom: SPCK publication. [ Links ]

Eichrodt, W. 1961. Theology of the Old Testament Vol.1. Westminster: John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Escobar, S. 2003. The new global mission: The gospel from everywhere to everyone. Downers Grove, Illinois InterVarsity Press. [ Links ]

Eskew, H. & McElrath, H.T. 1995. Sing with understanding: An introduction to Christian hymnology, 2nd edition, revised and expanded. , Nashville, Tennessee: Church street press. [ Links ]

Foglio, A. & Stanevicius, V. 2006. Scenario of glocal marketing as an answer to the market globalization and localization. Part I: Strategy scenario and market, Klaipeda, Lithuania: Vadyba/Management. [ Links ]

Fowler, J.A. 1995. The oppression and liberation of modern Africa: examining the powers shaping today's Africa, Potchefstroom: Instituut vir Reformatoriese Studie (IRS). [ Links ]

Frame, J.M. 1996. Worship in Spirit and Truth: A refreshing study of the principles and practice of biblical worship, New Jersey, USA: P & R Publishing. [ Links ]

Fujino, G. 2010. "Glocal" Japanese Self-Identity: A missiological perspective on paradigmatic shifts in Urban Tokyo. [ Links ]

Garside, C. 1979. The origins of Calvin's theology of music: 1536 - 1543. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, [ Links ].

Giulianotti, R. 2012. Glocalization and sport in Asia: Diverse perspectives and future possibilities. Sociology of Sport Journal, 2012:29. [ Links ]

Green, M. 2005. Translating the Nation: Phaswane Mpe and the Fiction of Post-Apartheid. Scrutiny2 10.1:3-16. [ Links ]

Griffiths, G & Clay, P. 1982. Hillbrow. Cape Town: Don Nelson. [ Links ]

Gritters, B.L. 2008. Music in worship: The reformation's neglected legacy, Protestant Reformed Theological Journal Vol.1, no.1 (November). [ Links ]

Guder, D. L. 1998. Missional church: from sending to being sent. (In Guder, D.L., ed. Missional church: a vision for the sending of the church in North America. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. p. 1-17. [ Links ])

Guroian, V. 1997. Moral formation and Christian worship. The Ecumenical review, 49 (3): 372 - 378. [ Links ]

Hallen, B. 2009. A short history of African philosophy, Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Hasting, A 1976. African Christianity. London: Geoffrey & Chapman. [ Links ]

Hawn, C.M. 2003. Gather into one-Praying and singing globally. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William & Eerdmans publishing company. Heidelberg Catechism, Lord's Day 35, question 96. [ Links ]

Hodges, J.M. 2010. Beauty in music: inspiration and excellence for Veritas Academy Fine Arts Symposium. Lancaster: Veritas Academy Press [ Links ]

Horton, M. 2002. A better way: Rediscovery the drama of God-centered worship. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Books. [ Links ]

Kaiser Jr.,W.C. 2000. Mission in the Old Testament - Israel as a light to the nations. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Books [ Links ]

Khondker, H.H. 2004. Glocalization as globalisation: Evolution of a sociological concept. Bangladesh: e-Journal of Sociology, 1(2) July: [ Links ]

Kimball, D. 2003. The emerging church: vintage Christianity for new generations. Zondervan. [ Links ]

Kirby, Percival R. 1959. The Use of European Musical Techniques by the Non-European Peoples of Southern Africa." Journal of the International Folk Music Council, Vol. 11: 37-40. [ Links ]

Kirk, J.A. 1999. What is mission? Theological explorations. London: Darton Longman and Todd. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, J.N.J. 1994. Mission - Where? (In Kritzinger, J.J. & Meiring, P.G.J. & Saayman W.A. On Being Witnesses. Johannesburg: Perskor Book Printers). [ Links ]

Kruger, D. 2007. "A high degree of understanding and tolerance": veranderende denke oor die moderne Gereformeerde Kerklied. Koers, 72(4): 649-669. [ Links ]

Leaver, R. 2007. Luther's Liturgical Music: Principles and Implications, Lutheran Quarterly Books. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, [ Links ].

Levitt, T. 1983. The globalization of market, Harvard Business Review, May-June, Boston. [ Links ]

Liesch, B. 1996. The new worship:Straight talk on music and the Church, Grand Rapid, Michigan: Baker Book House company. [ Links ]

Lightfoot, J. B. 1892, Saint Paul's Epistles to the Colossians and to Philemon, Zondervan, Grand Rapids., Reprinted, 1959, Macmillan and Co., London. [ Links ]

Lucia, Christine (ed.). 2005. The World of South African Music: a Reader, Newcastle. [ Links ]

Ludik, B. 2008. Liturgiese inkleding: 'n moderne oogpunt. Vir die Musiekleier, 35: 9-18. [ Links ]

Marlowe, W.C. 1998. The Music of Missions: Themes of cross-cultural outreach in the Psalms. Missiology 26 (445-456). [ Links ]

McLaren, B.D. 2007. Everything must change. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson. [ Links ]

Merriam-Webster On-line Dictionary, 2015. Encyclopaedia Britannica online. Accessed 30 June 2015 from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/parameter [ Links ]

Miller, H.M. 1960. History of music. New York: Barnes and Noble Inc. [ Links ]

Milne, B. 2007. Dynamic diversity: Bridging class, age, race and gender in the Church. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity [ Links ]

Mpe, P. 2001. Welcome to Our Hillbrow. Scottsville: University of Natal Press. [ Links ]

Muller, C.A. 2004. South African Music: A century of traditions in transformation (World Music Series). Oxford, England: ABC CL10, [ Links ].

Newbigin, L. 1986. Foolishness to the Greeks: The gospel and Western culture. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans [ Links ]

Newbigin, L. 1998. Trinitarian doctrine for today's mission. Carlisle, UK.: Paternoster. [ Links ]

Nketia, J.H. Kwabena. 1974. The Music of Africa. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. [ Links ]

Nolan, A. 1976. Jesus before Christianity: The gospel of liberation, Cape Town, David Philip. [ Links ]

Piper, J. 2010. Let the nations be glad! - The supremacy of God in missions, 3rd Edition. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic, [ Links ].

Plato, Republic,in: Shorey P (tr.) 1953. The Loeb Classical Library. Vol.5. London: William Heinemann. [ Links ]

Reid, W. S. 1971. "The Battle Hymns of the Lord: Calvinist Psalmody of the Sixteenth Century" Sixteenth Century Essays and Studies, ed. Carl S. Meyer, The Foundation for Reformation Research, St. Louis, MO. [ Links ]

Robertson, R. 1992. Globalization: Social theory and global culture. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Roper, D.L. 1994. Wanted: a new song unto the Lord. (In A window on the arts - Christian Perspective. Bartholomew, C. ed.). Potchefstroom: PU for CHO. [ Links ]

Rothra, J.L. 2009. A historical and critical analysis of music as a method of evangelism http://www.jrothraministries.com/pdfdocs/MusicandEvangelism.pdf, accessed 20/01/2016) [ Links ]

Saayman, W., 2010, 'Missionary or missional? A study in terminology', Missionalia 38(1), 5-16. [ Links ]

Solomom, J., 1992, Music and the Christian, Probe ministries, Plano, Texas, USA. [ Links ]

Smith, W.S. 1962, Musical aspects of the New Testament. Amsterdam: unpublished dissertation [ Links ]

Stott, J. 2007. The Living Church - conviction of a life-long pastor. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press. [ Links ]

Strydom, W. M. L. 1994. Sing nuwe sange, nuutgebore: liturgie en lied. Bloemfontein: UOVS. [ Links ]

Totius, 1977. Versamelde Werke X. Eeufees-uitgawe. Kaapstad: Tafelberg Uitgewers Bpk. [ Links ]

Van Der Walt, B.J., 1997, Afrocentric or Eurocentric? Our task in a multicultural South Africa, PU vir CHO, Potchefstroom. [ Links ]

Van Engen, C. 1991. God's Missionary People: Rethinking the purpose of the local Church. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Books. [ Links ]

Van Engen, C. 1996. Mission on the way - Issues in mission theology. Grand Rapids: Michigan: Baker Books [ Links ]

Van Rensburg, F.J. 2007. Seminar on research methodology. Potchefstroom: North-West University [ Links ]

Webber, R. 2004. Blended Worship (In Basden, P. & Engle, P., eds. Exploring the worship spectrum: six views. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. p. 175-191. [ Links ])

Webber, R. E. 2008. Ancient-Future worship: proclaiming and enacting God's narrative. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books. [ Links ]

Werner, E. 1966. The music of post-Biblical Judaism, The new Oxford history of music, London: Oxford University press [ Links ]

West, G. 1993. Contextual Bible study. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster publications. [ Links ]

Westermeyer, P. 1998. Te Deum: The Church and music, Minneapolis: Fortress press [ Links ]

Westermeyer, P. 1998. Let Justice Sing: Hymnody and Justice. Collegeville: The Liturgical Press [ Links ]

Westminster Confession of Faith, chapter 21, section 1. [ Links ]

Wiersbe, W.W., 1989, The Bible Exposition Commentary. 2 vols, Scripture Press, Victor Books, Wheaton. [ Links ]

Willis, J. 2010. Church music and Protestantism in post-Reformation England - discourses, sites and identities. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. [ Links ]

Wilson-Dickson, A. 1992. The story of Christian music from Gregorian chant to black gospel - an authoritative illustrated guide to all the major traditions of music for worship. Oxford, England: Lion Publishing corporation. [ Links ]

Witvliet, J.D. 2003. Worship seeking understanding: windows into Christian practices, Grand Rapid, MI: Baker Academic [ Links ]

Wright, C.J.H. 2006. The mission of God: unlocking the Bible's grand narrative. Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press [ Links ]

Wright, C.J.H. 2010. The mission of God's people - A biblical theology of the Church's mission. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House [ Links ]

1 Ecclesiastical School, North West University, Potchefstroom-campus, e-mail: muswubi@gmail.com