Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Missionalia

On-line version ISSN 2312-878X

Print version ISSN 0256-9507

Missionalia (Online) vol.44 n.2 Pretoria 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.7832/44-2-150

ARTICLES

Youth intervention through training and equipping in the midst of challenges and crisis. The LIFEPLAN® programme as a possible solution

Fazel Ebrihiam Freeks1

ABSTRACT

The youth in contemporary South Africa seems to face massive challenges and experience problems such as substance use and drug abuse, violence, rape, child trafficking, prostitution, etc., lead to the lives of many young people being destroyed. Farming communities in the Christiana district of the North-West Province of South Africa struggle with poverty, unemployment, alcoholism, violence, occultism and Satanism. Statistics indicate a drastic decline in morals, values, standards, ethics, character and behaviour and society seems to indulge in crisis after crisis. Millions of young people growing up as orphans and even more, without a father figure in their lives, declining education in the schools and frustration with massive unemployment among those who have left school. This article focused on the youth of the Christiana district of South Africa as a large harvest to be reaped through holistic missional outreach programs that will give hope and enrich the lives of young people. The article also aimed to emphasize the LIFEPLAN® programme in a constructive creative critical way from a missio Dei perspective. Going missional2, and using in this context a programme require shifts in one's thinking and behaviour.

Keywords: youth intervention, training and equipping, challenges, crisis, LIFEPLAN®, programme, possible solution

1. Introduction and background

This research focussed on lessons learnt from the roll out of the LIFEPLAN® youth development programme and a mission Dei perspective (mission of God) among the poor and unemployed youth in the North-West Province of South Africa. Mission is an activity and amplification of the very being of God (Dames 2007:41; Niemandt 2016:7). It is further something which God does and God should be seen as the great missionary (cf. Bosch 2009:519; De Beer 2012:5) in an intervention programme such as LIFEPLAN®. The research3 is still a work in progress and the data provided within this article has already revealed that the research is not only relevant, but crucial for youth intervention, outreach and holistic youth development in communities. If communities are taking part in the mission Dei, they represents God's mission in the world and mission will then be part of their work and existence because mission is the concern of the triune God (Father, Son and Holy Spirit). The Father send the Son and the Son send the Holy Spirit (Mt 28:18-20; De Beer 2012:62; Hill 2012:153).

The Christiana community, a market place4where people connect and experience a way of life together but where Jesus can invade through mission (McNeal 2009:13-14; Wyngaard 2015:413). This community is however riddled by youth crises, such as unemployment and a vast array of challenges of community break down, associated with the economic and social situations in this area.

The Christiana district is an agricultural district on the banks of the Vaal River in the North-West Province of South Africa, with a population of 15,322 inhabitants. Christiana is located on the N12, between Bloemhof and Warrenton, on the way to Kimberley in the Northern Cape. Christiana is the administrative centre of Lekwa-Teemane Local Municipality (Anon. 2013).

The researcher realised, with support from the North-West University, that this community would be enriched through a programme that would train and equip young people with knowledge and skills to make better choices within the challenges that they have to face in their daily lives. Therefore, God calls and inspires individuals to reach out to young people through ministry because youth ministry is grounded in the missionary nature of God (Wyngaard 2015:411). These has given rise to the implementation of the LIFEPLAN® Training and Equipping Programme. The program has been introduced and implemented in this area since 2011. Four hundred and eighty six (486) young people have already been part of it.

2. Problem statement and youth challenges in the Christiana district

In the last few decades, South Africa especially has evidenced a decline in acceptable behaviour, character, values, standards, ethics and morals, and it is specifically observed in the behaviour of young people and the youth of today (Georgiades et al., 2013:1473-1476; Logan-Greene et al., 2012:373-374; Freeks 2015:1; Freeks 2013:1-3, Freeks 2011:1-4). The Christiana district in South Africa seems to be a typical example of massive challenges among the youth in rural farming districts in South Africa. Qualitative empirical research through interviews with key community leaders, like the head of the police, social workers working in the area, school principals, church leaders, managers of farms and even participants has revealed the following problems and challenges that the communities are struggling with:

• School performance in the area is a serious problem: some learners do perform well but many others underperform.

• Many of the learners who come from various farms in the area are functionally illiterate, but others underperform because of a lack of vision as well as simple laziness.

• Learners who can't read and can't spell, and therefore fail, often cause problems for teachers and underperformance is often mentioned as a source of disturbance in the school-system.

• Learners often do not have good career guidance and career choices, thus resulting in negative attitudes towards the future as well as a range of other 'improper' attitudes.

• They are often rude and unruly and disinclined towards working in class.

• They often appear to lack positive values and are frequently disrespectful; a picture that seems to be escalating by the day. Such students often drop out of school and involve themselves in gangsterism, drug and alcohol abuse and an array of criminal activities such as rape, theft and murder.

• Many instances of burglary and theft, in which learners have been involved, have been reported to the police.

Teenage pregnancy is a serious concern and records indicate that its incidence is around 9%, particularly with regard to girls between 16 and 18 years. One case involved a sixteen (16) year old girl giving birth to her second child, in all likelihood having had her first child when she was fourteen (14) years old.

Drug abuse by learners is an additional, serious concern in the area and the society has been referred to as sick as a result of the prevalent use of drugs. Learners smoke cannabis, glue and use various types of tablets on school grounds. This naturally affects their behaviour in class. This drug problem does not, of course, only affect the schools but the broader community as a whole. Compounding the drug problem is alcohol abuse by learners. Such abuse is one of the main problems in the schools, since learners spend much of their time at drinking places such as taverns instead of in the classrooms.

Gangsterism is generally invisible on the school grounds but it presumably functions, operates and develops in secret. Gangs operate in communities in such a way that learners are directly or indirectly influenced by the activities of these gangsters. Learners have been found carrying dangerous weapons in their school bags e.g. knives, sticks and pangas. Other reported incidents include learners fighting in class, learners stabbing other learners and teachers and even learners trying to shoot other learners. Naturally, some teachers have taken to weapons to protect themselves.

The lack of involvement of the youth in church-life is a serious concern to most of the Christian pastors that have been interviewed. Young people often just refuse to attend church, and very low church-attendance is the norm. It would appear that participation in the activities of the church is of no importance to many of them. Instead, the youth appears to be rather driven and influenced by politics, a fact which often causes tension and havoc in some of the churches. The involvement of young people in Satanism is also a burning issue for the churches and in the communities. Churches seem to lack relevant youth programs and trained youth leaders to facilitate outreach to young people in the communities.

Unemployment among the youth is a huge problematic factor, not only in terms of its impact on the churches but also in relation to the community as a whole. Approximately 50% of the youth in Christiana is unemployed. Youth unemployment is in a sense the underlying factor behind all the other problems among the youth in Christiana.

The number of orphans in Christiana is another burning issue for most of the relevant role-players, particularly over the last three (3) years. Child-neglect occurs frequently in the community: parents often do not care at all for their children and child-headed households are at the order of the day. Naturally, as a result, many of these children do not make quality life-decisions.

Abortion and HIV/AIDS-related matters are additional concerns in Christiana. The prevalence of HIV infection and transmission is high and the life-expectancy of the population is receding alarmingly.

Pastors, school principals and the social worker who have been interviewed expressed the opinion that religion should be advocated as a beneficial option to assist young people to obtain basic life skills. It is clear that young people are currently engaging in irresponsible behaviour because they have not been taught properly to follow certain values: obedience, respect, honour, honesty, friendliness, peacefulness, forgiveness, discipline, thankfulness, forgiveness, helping, etc. As a result, they are irresponsible and often make bad life-choices.

According to the South African Police Services (SAPS) (2013) statistics, it shows that Christiana has youth problems that need urgent attention. Some of the crime categories are murder (9%), sexual crimes (61%), robbery (44%), damage to property (67%), burglary (211%), theft (50%), drugs and alcohol (45%), kidnapping (5%), etc.

3. Research question

From the above background and problem statement the question arises: To what extent does the LIFEPLAN® Training and Equipping Programme for youth in the Christiana district of South Africa provide a tool for effective Christian missional outreach to the youth in rural areas?

Questions arising from this main research question are the following:

• What are the main characteristics of the challenges that youth development is facing in the Christiana district?

• What are the goals and objectives of the LIFEPLAN® Training and Equipping Programme?

• What impact has the program had so far in the Christiana district?

• Why is holistic missional and evangelistic outreach to the youth a vital aspect of God's mission?

• Could the LIFEPLAN® Training and Equipping Programme be part of God's mission as a tool for Gods people in the Christiana district, reaching the youth?

• How could the programme perhaps be improved, and be helpful for youth ministry in other rural areas?

4. Purpose of the research

The purpose of the investigation was to determine how the LIFEPLAN® Training and Equipping Programme can be a tool for effective holistic Christian missional outreach to the youth in rural areas.

5. Research objectives

Specific objectives of the research are:

• To identify the main characteristics of the challenges that youth development is facing in the Christiana district.

• To summarise the goals and objectives of the LIFEPLAN® Training and Equipping Programme.

• To evaluate what impact the program has had so far in the Christiana district.

• To point out that holistic missional and evangelistic outreach to the youth are vital aspects of God's mission.

• To evaluate whether the LIFEPLAN® Training and Equipping Programme could be part of God's mission and be used as a tool for God's people in the Christiana district in reaching the youth.

• To improve the program to be helpful for youth ministry in other rural areas.

6. Research methodology

6.1 Research Design

In this article, the research design is embedded in using the quantitative approach.

6.2 Research Method

Information was gathered in the form of questionnaires and the gathering of statistical results of impact of the LIFEPLAN® Training and Equipping Programme in the Christiana district. According to De Vos (2005) (cf. also Freeks & Lotter 2011) the use of quantitative approaches is effective in undertaking this type of research.

6.3 opulation

Respective to this study, the population consisted of participants (farm workers) for quantitative research (questionnaires). All participants in the research were from the broader Christiana district in the North-West Province.

6.4 Sample

The researcher attempted to investigate the lived experiences of participants (farm workers), using questionnaires.

6.4.1 Sampling

Participants (farm workers) were selected because they were trained and equipped with the LIFEPLAN® Training and Equipping Programme.

6.4.2 Sample size

The participants (farm workers) for the quantitative research (questionnaires) were 151 in total.

6.5 Data gathering

The researcher and the Coordinator for the various farms identified the participants (farm workers) from the different farms in the Christiana district and contacted their farm managers by telephone and arranged for appointments, the time and place where questionnaires were going to be conducted. Factors such as anonymity, confidentiality, privacy, risks, withdrawal and even possible termination were discussed (Botma et al. 2010:13-14).

For this quantitative research five (5) questions (i.e. general well-being=10 sub-questions; relationships, self-image and self-esteem development=10 sub-questions; emotions=10 sub-questions; quality of life=16 sub-questions and spiritual well-being=12 questions) from the themes of the LIFEPLAN® Training and Equipping Programme were formulated.

6.6 Data analysis

The data obtained through the questionnaires was processed by the Statistical Consultation Services of the North-West University (Potchefstroom Campus).

6.7 Ethical considerations

The ethical aspects are there to protect the rights and integrity of the participants and the researcher. The individuals or participants are autonomous, and have the right to self-determination and this right should be respected (Burns & Grove 2004:186). Informed consent was obtained, which entails informing the research participants about the overall purpose of the investigation (Kvale & Brinkmann 2009:70). A consent was issued to the potential participants. The purpose and nature of the research were explained clearly and concisely in the consent and during the briefing and debriefing stage. Participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any time he/she felt uncomfortable.

7. The importance of youth evangelism and missional outreach to the youth

Missions and evangelism originate in God and young children are part of God's mission. Missions have always been part of the Christian church, from the apostolic movement to deploying missionaries, as a way for the church to make disciples of all nations (Elton 2013:64). To evangelize the youth implies a spiritual practice because God is at work among the young people (Kujawa-Holbrook 2010:17-18). Ministering the youth is primarily relational and informal and it is between childhood and adulthood, which combines relational and evangelical impulses (Elton 2013:63-64). Elton also mentioned that youth ministry helps people to discover a Christian way of life. Steffen (2011:79) underlined the fact that the real mission ofJesus is to proclaim the Good News that God's Reign has come. The Gospel must be preached for God's honour and because of His grace through Jesus Christ (Van Wyk 2014:10).

In this research it is vital to comprehend the importance of targeting the youth in missions and evangelism. It is also important to understand the goal and motivation for missions (cf. De Beer 2012:48). Understanding the ultimate goal of missions, one should first understood that the entire creation exists for the glory of God. Missions have the capacity to transform adolescents (Beyerlein et al. 2011:783), and as human beings, we have a part in that reason, and our primary goal is to bring glory and honour to God (Wright 2010:53). May et al. (2005:3) indicated that, throughout the entire Bible, the glory and honour is the very foundation of missions and evangelism. They also mentioned that it is not usual and ordinary to say that young children matter and are important because they do matter and they are important. They matter to God, the church and to the Son of God, Jesus Christ. They are beings who are made in the image of God, and one should boldly say that the Church, for example, can't be the Church without children and youth (May et al. 2005:3). Boyd (2010:53) substantiated that young children are not only the Church of tomorrow, but already the Church of today. Jesus Christ, for that reason, stated in Mark 10:14 that the children must come to Him and they should not be stopped because the Kingdom of God belongs to those who are like these children. Many people, however, experience problems with child and youth evangelism and missions (Horton 2010:30-32). They feel that children and the youth are too insignificant or immature. Evans (2012:84), on the other hand, stated that the consequences of young children reading the Bible need urgent research. But still, for all matters of doctrine and practice, the Bible is the authoritative source, especially to teach young people. This will ensure that they are grounded in biblical truth so that they can establish a good, solid biblical foundation (Widstrom 2011:11).

According to Bisschoff (2014:15) young children should learn to serve God with their intellect or understanding. Even if they are young, the Will of God should be taught to them through the Bible (Van der Kooy 2014:17). Ward (2009:53-54) also supported the idea and said that the young children should be evangelized because it is important to teach them about the Bible and about worship. While understanding that the Bible is for young children too, Beckwith (2004:123) states that the Bible should not be used to teach young children moral lessons but instead to introduce young children to God and tell them God's story and His ways (Beckwith 2004:126). In the same context, Botma (2012:28) is of the opinion that every individual has to somehow make their own decisions, and here missions and evangelism are vital for young children. All individuals are responsible for their own lives and also their own spiritual development, but they need assistance and this assistance can be provided through missions and evangelism (Botma 2012:76). Through this assistance, they need to be taught and brought up in a Godly way. This could possibly be realized through missions and evangelism. It should also be kept in mind that the Bible is explicit when it states that parents and the church have a responsibility to help the youth to mature in Christ (cf. Eccles. 22:6).

Many times the youth raises all sorts of questions about God and the Bible. Even if they have tattoos and piercings it is important and necessary to reach out to them in love through missions and evangelism (Copeland 2012:13). Their spirituality is essential for their whole well-being (Hodder 2009:197-199). The faith of a fifteen (15) year old is as important as a sixty-five (65) year old (Snailum 2012:171).

Missional outreach and evangelism to young children should therefore be a focal point in the Kingdom of God so that God, as stated earlier, can be glorified and worshipped (Wright 2010:53-54). It is evident that ministry with young people has exploded after three decades as a certain form of specialized professional ministry and also as a field of study in theological education (Dean 2010:108). Youth ministry, missions and evangelism should not be seen as forms of force to pressurize the youth with our own religious values, but rather as doing missions and evangelism for the glory of God. Through doing missions and evangelism, the youth is empowered to become agent-subjects-in-relationships. It is also helping to advance fullness-of-life-for-all (Steffen 2011:80). Through missions and evangelism, we should go where the youth are (Gouger 2013:7) and bring a message to them that God loves them (Kennedy 2010:40). It is, after all, God who calls and gathers people, whether they are children or the youth, or others for His everlasting love and glory (De Beer 2012:51).

The process of communication is vital and one of the most rewarding experiences when doing missions and evangelism with young people. The message, through the communication channel, should be very clear and transparent, because God and Jesus Christ are ministered to them. It is more about practice than about theory. It is getting involved and interaction with other people, especially young people (cf. Ward et al. 1994:25). Evans (2012:86) mentioned the idea that youngsters are searching for new ways of being religious and we are required to adjust the way we communicate our Christian faith to them and should listen to what they have to say. Learning to listen is, according to Penner (2003:44), of utmost importance, because the youth are better talkers than listeners. It is at this point that many people find it extremely difficult to reach the youth through missions and evangelism (Penner 2003:44).

In the 21st century young children are described as the most sought after generation and the most protected ones (Beckwith 2004:29). Young children are in no sense parent's liabilities, they are in fact God's reward, God's gift, God's grace and favour to parents. God values them, and so should we. They should never be a nuisance to us (Mueller 1999:6). Although these young children mature and grow older, we may find it very hard to see them as gifts because of the challenges as well as their difficult times and behaviour. But, according to Mueller (1999:6), it does not matter how old they grow, they are still gifts from God, and once a gift from God, always a gift from Him. We should therefore treasure the gift of our young children (Mueller 1999:6).

8. The role of universities

The importunate appeal of the South African government is that universities should be involved in the transforming of societies to help reduce some of these challenges among the youth of South Africa. Therefore, the North-West University developed a strong desire to be involved in societies in our province and to do intervention through training and equipping programs. That has led to the implementation of the LIFEPLAN® programme four years ago. The program has the potential and possibility to contribute toward character formation and to reduce some of the destructive challenges facing the youth.

9. The LIFEPLAN® Training and Equipping Programme

The LIFEPLAN® Training and Equipping Programme supports the youth to make healthy and quality choices for their lives. Its contributing role is in strengthening, motivating, inspiring and developing young people, especially with their choices and decision-making regarding behavioural challenges (Freeks 2008).

9.1 The history of the LIFEPLAN® Programme

The North-West University aspires to be a pre-eminent university in Africa, driven by the pursuit of knowledge innovation and community involvement to contribute in providing solutions for reconstruction and development of communities.

Through guided interventions the LIFEPLAN® (Life Inequalities amongst Persons addressed by means of Purposeful Living and Nutrition interventions) programme was implemented and presented. The presenting of the programme started in 2008, and has been running for the past eight (8) years. The programme had reached more than 860 participants who were trained and equipped with a variety of life skills.

The LIFEPLAN® Training and Equipping Programme was accredited on the 14th of September 2010 by the Institutional Committee for Academic Standards (ICAS).

9.2 What is LIFEPLAN®?

LIFEPLAN® follows a path of core lecturing exercises and activities, that build knowledge, promote interpersonal skills and trust through contact and sharing, build thinking and planning skills, and build motivation and commitment to action. The programme activities comprise:

• Presentations

• Interactive activities

• Discussions

• Sharing

• Exercises

9.3 The aim, layout and design of the LIFEPLAN® Programme

LIFEPLAN® is specially designed to guide and to assist participants and facilitators when offering or conducting training and developing sessions for the youth, illiterate and semi-literate individuals and farm workers who want to be equipped and who want to become knowledgeable and self-sustainable.

Quality of life is directly affected by people's physical health, the availability or absence of health services, quality of health services, available money and money spending practices, family violence and people's coping mechanisms to deal with life and all its facets that also, to a large extent, determine mental health. Therefore, the activities focus specifically on the holistic promotion of health in context, i.e. restoring, maintaining, and promoting bio-psycho-social health and health systems, as to add to the best possible quality of life and well-being for the population, through research (basic and applied), training (building capacity) and enhancement of service delivery.

The framework for the LIFEPLAN® education and training programme was compiled, based on the Maslowian hierarchical needs assessment scale and in-depth research. Maslow's theory proposed a hierarchy of five innate needs that activate and also direct human behaviour (Schultz & Schultz 2013:246). The theory of Maslow is widely used in educational areas. Maslow himself published some of his work in educational studies. The LIFEPLAN® programme addresses poverty amongst the most vulnerable through human development and training in life skills, in order to improve their well-being in terms of health, nutrition and choice, all combined in a model where sustainability in terms of family and social support networks and structures, behavioural, hygienic and nutritional practises and financial impact can be tested (Freeks 2008).

LIFEPLAN® has a prerequisite training and developing manual for each group of volunteers who wants to take up the opportunity to be equipped, to be trained and to be developed so that they can be skilled, self-sustainable, independent and hardworking. The goal is that after completing LIFEPLAN® participants will have developed a valid self-image to take healthy pride in their personal ability, capability, potential, skills, experience and co-operation and develop a concern to care for others in their communities. An additional advantage and privilege for these participants is the opportunity to start their own businesses and to direct their own lives.

10. Results and discussions

It was clear that the Christiana district was struggling with vast problems and challenges for developing the youth in this rural area. However, the LIFEPLAN® Training and Equipping Programme, in the four (4) years of its implementation in the Christiana district, seems to be making an impact and making inroads on alleviating youth challenges. The LIFEPLAN® Programme was offered to ten (10) different farms in the Christiana district for approximately 486 participants (Nieuwoudt 2013).

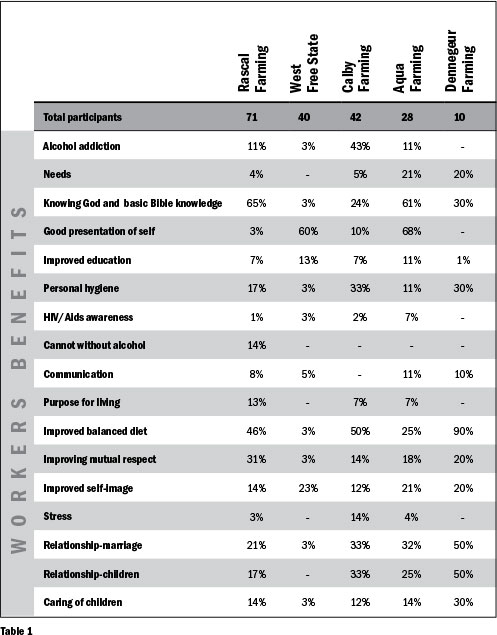

Looking at Table 1 as a summary of the investigation, it appears that the LIFEPLAN® Training and Equipping Programme already has a positive impact on participants. Witnesses such as the co-ordinator of the LIFEPLAN® Programme in Christiana and management from the various farms at Christiana where the programme has been presented and is still presented, confirmed the impact of the programme because of the conduct and behaviour of their workers on the various farms. However, an on-going research project wants to evaluate the programme further, deeper and more thoroughly and consider improvement.

These achievements from the co-ordinator in Christiana indicated that both managers and workers from the different farms in Christiana have a positive approach toward the LIFEPLAN® programme. In summary, the following aspects from the LIFEPLAN® programme impacted the lives of workers positively:

Respect for self and others, positive self-image and trust, personal hygiene, healthy lifestyle, less alcohol use and abuse, better financial management, better family relations, control of emotions and rage, responsibility and strength in their faith. The workers also indicated that they benefit and learn a lot from specific themes in the programme, for example:

• The aspect of knowing God and the Bible better, 65% benefit from a total of 71 participants.

• The use and abuse of alcohol, 11% benefit from a total of 71 participants.

• Personal hygiene, 33% benefit from a total of 42 participants.

• Healthy eating, 90% benefit from a total of 10 participants.

• Respect, 31% benefit from a total of 71 participants.

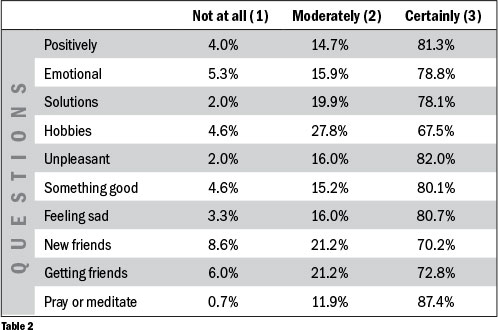

• Relationships and marriages, 50% benefit from a total of 10 participants, etc. It is significant that 87.4% of the participants pray or meditate when they have a problem opposite the .7% who don't, and 11.9% who moderately pray or meditate when they have a problem.

• Spiritual well-being

This specific question in the questionnaire was based on the importance of God, your relationship and your faith in Him.

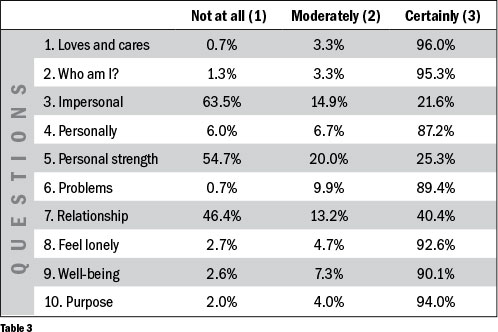

In table 3, questions 3, 5, 7, 11 and 12 about God are impersonal don't get personal strength and support from God, don't have a relationship with God, ancestral spirits and traditional healers are indicated low while questions 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 9 and 10 are indicated high.

It is notable that 96.0% of the participants indicated that they believe that God loves them and cares about them against the 0.7% who don't believe that at all. Irrespective if the youth believe that God loves them, if they want to be a missional community (mission ecclesia) within the community and want to grow towards a mission Dei, they should turn back to God because His honour and praise concerns the mission Dei (Jansen 2015:21). Hence, it is disappointing to see that 21.6% believe that God is impersonal and not interested in them against the 63.5% who don't believe that at all and 14.9% who moderately believe that God is not interested in their lives. Even with regard to personal strength and support from God, 25.3% indicate that they certainly don't get it from God as opposed to 54.7%, who don't agree on that. However, from the 151 participants, 95.3% indicated that they know who they are and they know where they come from, which is a central theme in the LIFEPLAN® Training and Equipping Programme. Participants also indicated that 87.2% of them have a personally meaningful relationship with God against the 6.0% who don't have a relationship and 6.7% who have a moderate relationship. Relationship with God is primary and important because human beings are created to serve and glorify God through their thoughts, words and actions (Corbett & Fik-kert 2012:55). Concerning the aspect that God is concerned about their problems, 89.4% indicated that God is, as opposed to the 0.7% who believe God is not and 9.9% who moderately believe God is. Biblical principles are crucial and tend to break down obstacles and problem areas that could possible hinders these participants. Therefore, the youth should consult the Bible which is God's principles to overcome these challenges and crisis in their lives (cf. De Beer 2012:61)

It is further overwhelming to see that 90.1% indicated that their relationship with God contributes to their sense of well-being and 94.0% who believe that there is a real purpose for their life. In contrast with the above, 50.3% honour, worship and ask blessings from their ancestral spirits (Badimo's) against the 27.8% who don't and 21.9% who moderately indicated on that. The very same scenario occurs with the traditional healers (sangoma's and inyanga's), where 35.1% indicated they consult them for advice about their life and future against the 47.7% who don't and 17.2% who moderately do. In general, it seems that for some of the participants spirituality is not that important as the other aspects are. Human beings are not only social, psychological or physical beings, they are also spiritual beings. Hence, spirituality with the focus on spiritual formation should be the most important aspect in the LIFEPLAN® programme. Spiritual formation is formation of the inner being of the human being and it results in the transformation of the whole person (body, soul/mind, spirit) (Porter 2014:250; Rm 12:2). Moral or spiritual formation strengthened the youth a meaningful transform society (Nel 2015:550). Notwithstanding is the essence of mission and evangelism the overflow of true spirituality, and the youth should be full of joy, reverence, worship and admiration for Jesus Christ as their mighty Saviour (cf. Buys 2014:135).

11. Critique, recommendations and opportunities of the LIFE-PLAN® Training and Equipping Programme

The LIFEPLAN® Training and Equipping Programme in its current state was effective in the South African context, where 80% of the population identified themselves with the Christian faith, especially those living in poor previously disadvantaged areas and districts of South Africa. The programme was developed to be used in the context of African young people. This might not be the case in other countries with regard to their religious demographic context. Therefore, the programme should be tested but also contextualized within other contexts in order to measure its effectiveness and impact in urban context and in first world countries such as the Netherlands, Portugal, Brazilian, South America, etc.

The LIFEPLAN® Training and Equipping Programme should include a strong focus on spirituality or spiritual formation because it is grounded in Scripture or involve engagement with Scripture (ecclesiology) and has the effect to form the inner part of the human being. Spiritual formation also focus on Jesus Christ, and those who follow Him live in God's presence with body, mind and soul in the midst of their challenges and crisis (cf. Mannion 2008:13).

The programme should also be tested in the Two-Thirds World, Three-Fourths World and majority world in Africa, such as Angola, Mozambique, South Africa, etc., where it might be beneficial because LIFEPLAN® after all is based on Christian living values as well as general living values.

The feedback and results received from the LIFEPLAN® programme were not all positive. The results from the structured interviews and naïve sketches illustrated the following: "LIFEPLAN® taught me nothing", "I learn nothing from the programme". However, this kind of response constitutes the exception rather than the rule because, from the sample size of 151 participants, 90% and more indicated a positive impact of the LIFEPLAN® Training and Equipping Programme.

It must also be investigated whether LIFEPLAN® can be effective within a context whereby participants exhibit higher levels of literacy because the programme was designed, developed and compiled to support participants who are under-developed, unemployed, illiterate, semi-literate to become skilled, self-sustainable, independent and hard working to direct their own lives.

The programme may develop more guidelines and a training manual for facilitators of the programme. In such a training manual the underlying philosophy goals and expected outcomes should be explained in more detail in order to motivate the facilitators in their presentation of the programme.

In contextualizing the programme, it might be necessary to consider the different learning styles of people from different backgrounds, i.e. Field Dependent and Field Independent learning styles.5

12. Conclusion

The LIFEPLAN® Programme may provide a significant opportunity for North-West University to partner with churches, schools and other community structures to transform broken communities in rural areas, but more research is needed. Such research should lay out more theological and missiological principles of holistic missional outreach to possibly improve the effectiveness and impact of the programme so that it can be presented as an effective tool for youth in urban context.

References

Anon. 2013. Christiana, North-West. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christiana, South Africa: North-West. Date of access: 20 Nov. 2013. [ Links ]

Beckwith, I. 2004. Postmodern children's ministry: ministry to children in the 21st century. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. [ Links ]

Beyerlein, K., Trinintapoli, J & Adler, G. 2011. The effect of religious short-term mission trips on youth civic engagement. Journal for the scientific study of religion, 50(4):780-795. [ Links ]

BIBLE. 1983. (NIV) Thompson Chain Reference Bible. Grands Rapids, Mich.: Zondervon Publishers. [ Links ]

Bisschoff, PLR. 2014. Kinders moet leer om die Here met hulle verstand te dien. Die kerk- blad, 116(3276):15-16, Feb. [ Links ]

Boyd, JC. 2010. Mission in context: a critique of a mission to children receiving the kingdom of God as a child. Congregational journal, 9(2):53-68. [ Links ]

Botma, Y., Greeff, M., Mulaudzi & Wright, SCD. 2010. Research in health sciences. Cape Town: Clyson Printers. 370 p. [ Links ]

Botma, EC. 2012. Pastoral guidance for the spiritual development of the adolescents of Little Falls Christian Centre. Potchefstroom: NWU. (Dissertation - MA). [ Links ]

Bowen, E. & Bowen, D. 1989. Contextualizing teaching methods in Africa. Evangelical missions quarterly, 25(3):270-275. [ Links ]

Burns, N. & Grove, SK. 2004. The practice of nursing research: conduct, critique, and utilization. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Jackson. [ Links ]

Buys, PJ. 2014. Missions in the fear of God. Journal for Christian scholarship, 3; 133-152. [ Links ]

Copeland, AJ. 2012. Ministry with young adults in flux: no need for church. Christian century, Feb. 8. [ Links ]

Corbett, S. & Fikkert, B. 2012. When helping hurts: how to alleviate poverty without hurting the poor and yourself. Chicago: Moody Publishers. [ Links ]

Dean, KC. 2010. OMG: a youth ministry handbook. Nashville: Abingdon. [ Links ]

De Beer, C. 2012. The characteristics of a missional church as part of the Mission Dei. Potchefstroom: NWU. (Dissertation- MA. [ Links ])

De Vos, AS. 2005. Qualitative data analysis and interpretation. (In De Vos, A.S., Strydom, H., Fouché & Delport, C.S.L. Research at grass roots. For the social sciences and human service professions 3rd ed. Pretoria: Van Schaik. p.333-334. [ Links ])

Elton, TM. 2013. Mergers and possibilities: the intersection of missiology and youth ministry. Missiology, 41(1):62-73. [ Links ]

Evans, A. 2012. Evangelism of young children: is an evolutionary understanding of original sin; possible. Old Testament essays, 25(1):84-99. [ Links ]

Freeks, FE. 2011. The role of the father as mentor in the transmission of values: a pastoral-theological study. Potchefstroom: NWU (Thesis - PhD. [ Links ])

Freeks FE & Lotter GA 2011. Waardes en die noodsaak van 'n karakteropvoedingsprogram binne kollegeverband in die Noordwesprovinsie: verkenning en voorlopige voorstelle. Koers, 76(3):577-598. [ Links ]

Freeks, FE. 2013. Dad is destiny: the man God created to be. Potchefstroom: Ivyline. [ Links ]

Freeks, FE. 2008. Manual for course facilitators: LIFEPLAN®. Potchefstroom: AUTHeR - (Africa Unit for Trans-disciplinary Health Research), NWU. [ Links ]

Freeks, FE. 2015. The influence of role-players on the character-development and character-building of South African college students. South African journal of education, 35(3):1-13. [ Links ]

Georgiades, K., Boyle, MH. & Fife, KA. 2013. Emotional and behavioural problems among adolescent students: the role of immigrant, racial/ethnic congruence and belongingness in schools. Journal of youth adolescence, 42:1473-1492. [ Links ]

Gouger, D. 2013. To evangelize youths who have drifted from church, go 'where they are'. National Catholic reporter, Mar - Apr. [ Links ]

Hill, G. 2012. Salt, light, and a city: introducing missional ecclesiology. Oregon: Wipf & Stock. [ Links ]

Hodder, J. 2009. Spirituality and well-being: 'new age' and 'evangelical' spiritual expressions among young people and their implications for well-being. International journal for children's spirituality, 14(3):197-212. [ Links ]

Horton, D. 2010. Ministry students ages of conversion with implications for childhood evangelism and baptism practices. Christian education journal, 7(1):30-51. [ Links ]

Jansen, A. 2015. 'n Holistiese perspektief op die mission Dei: 'n evaluering van die sending werk van die Christelijke Gereformeerde Kerken in KwaNdebele (RSA). Potchefstroom: NWU. (Thesis - PhD). [ Links ]Kennedy, JW. 2010. Youth with a passion. Christianity today, 54(12):40-45. [ Links ]

Kvale, S. & Brinkmann, S. 2009. Interviews: learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. 2nd ed. Los Angeles. Sage. [ Links ]

Kujawa-Holbrook, SA. 2010. Resurrected lives: relational evangelism with young adults. Congregations: 17-21, Spr. [ Links ]

Logan-Greene, P., Nurius, PS. & Thompson, EA. 2012. Distinct stress and resource profiles among at-risk adolescents: implications for violence and other problem behaviours. Journal of child adolescence social work, 29:373-390. [ Links ]

Mannion, G. 2008. Comparative ecclesiology: critical investigations. London: T&T Clark. [ Links ]

May, S., Posterski, B., Stonehouse, C. & Cannell, L. 2005. Children matter: celebrating their place in the church, family and community. Michigan: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

McNeal, R. 2009. Missional renaissance: changing the scorecard form the church. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Mueller, W. 1999. Understanding today's youth culture. Illinois: Tyndale. [ Links ]

Nel, RW. 2015. Remixing interculturality, youth activism and empire: a postcolonial theological perspective.Missionalia, 43(3):545-557). [ Links ]

Nieuwoudt, M. 2013. Indication of amount of participants who participate in the LIFE-PLAN® Training and Equipping Programme [e-mail]. 20 Nov. 2013. [ Links ]

NWU: Institutional Committee for Academic Standards, 2010. North-West University, Potchefstroom Campus. [ Links ]

Penner, M. 2003. Youth worker's guide to parent ministry: a practical plan for defusing conflict and gaining allies. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. [ Links ]

Porter, S.L. 2014. Philosophy and spiritual formation: a call to philosophy and spiritual formation. Journal of spiritual formation and soul care, 7(2):248-257. [ Links ]

SAPS (South African Police Service). 2013. Crime research and statistics-South African Police Service: Crime in Christiana (NW) for April to March 2003/2004 -2012/2013. http://www.saps.gov.za/statistics/reports/crimestats/2013/crime_stats.htm Date of access: 15 Nov. 2013. [ Links ]

Schultz, DP. & Schultz, SE. 2013. Theories of personality. 10th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. [ Links ]

Snailum, B. 2012. Implementing intergenerational youth ministry within existing evangelical church congregations: what have we learned? Christian education journal, 9(1):165-181. [ Links ]

Steffen, PB. 2011. Migrant youth and the mission of the church: a pastoral-theological reflection. http://www.sedosmission.com. Date of access: 11 Feb. 2014. [ Links ]

Thorne, S. 2008. Interpretive description. Walnut Creek, Calif.: Left Coast Press. 272 p. [ Links ]

Van der Kooy, R. 2014. Om aan eerstelinge God se wil te leer. Die Kerkblad, Feb. 17-18. [ Links ]

Van Wyk, JH. 2014. Preek die evangelie. Die Kerkblad, Feb. 9-10. [ Links ]

Ward, A. 2009. Let the children come. Leadership journal, Sum. 53-55. [ Links ]

Ward, P., Adams, S. & Levermore, J. 1994. Youth work and how to do it. Malta: Lynx. [ Links ]

Widstrom, BJ. 2011. A view from inside the fishbowl: a cultural description of evangelical free church youth ministry. Journal of youth ministry, 9(2):7-33. [ Links ]

Wright, CJH. 2010. The mission of God's people: a Biblical theology of the church's mission. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. [ Links ]

Wyngaard, J. 2015. Missio Dei and youth ministry: mobilizing young people's assets and developing relationship.Missionalia, 43(3):410-424). [ Links ]

1 Dr Fazel Ebrihiam Freeks is a Senior Lecturer and Coordinator Community Engagement in the Faculty of Theology at North-West University, Potchefstroom Campus. He can be contacted at 10589686@nwu.ac.za

2 McNeal (2009:xvi)

3 This research is part of a thesis

4 4 Market place - where people congregated (Wyngaard 2015:413)

5 When we add to this the findings of educational psychologists, who are concerned with describing how people learn in terms of behaviour, we learn of two learning styles which appear to correspond rather well to the functions of the left and right-brain. Based upon the social environment preferred by each style of learning, these two basic learning styles are called "field-independent" and "field-dependent." The field-independent learners "approach their tasks analytically, separating the elements. They pay close attention to internal referents and are less influenced by social factors" (Earle and Dorothy Bowen, "Contextualizing Teaching Methods in Africa," Evangelical Missions Quarterly, July, 1989, p. 272). On the other hand, field-dependent learners "approach situations 'globally,' that is, they see the whole instead of the parts. They rely on external referents to guide them in processing information. They have a social orientation."