Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Missionalia

On-line version ISSN 2312-878X

Print version ISSN 0256-9507

Missionalia (Online) vol.43 n.2 Pretoria 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.7832/43-2-91

ARTICLES

Renaissance and rebirth: A perspective on the African Renaissance from Christian mission praxis

ABSTRACT

The authors analyse the present state of the debate with regards to the African Renaissance, and come to the conclusion that the religious or faith dimensions have been neglected thus far. They regard this as a mistake, given the very important position that religious adherence occupies in African society. They propose that this mistake be rectified, arguing specifically from the perspective of Christian mission, where rebirth plays an important role. They propose that the implementation of the African Renaissance be correlated to the seven stages of the cycle of mission praxis.

Keywords: African Renaissance, mission praxis, rebirth, matrix, religiosity, spirituality, agency, reflexivity, contextuality, discernment

1. Introduction

The term "African Renaissance" has recently turned out to be a fashionable catch phrase that goes up any wall to label a spaza shop in a dusty township street, a fast-food outlet somewhere around the corner to lure passers-by, a bash that lays claim to musical sounds of the African Renaissance and some kind of jazz festival proudly hoisting an advertisement to the claims of a new concoction of African sounds. (Banda 2010:1)

These words admirably verbalise what may be called the obsession with an "African Renaissance"3 which characterised many debates especially during the reign of former President Thabo Mbeki as head of state of the South African Republic from 1999 to 2008. Although Mr Mbeki has since lost his position as President of the South Africa, the debate is still ongoing. This debate was recently once again in the public eye when the Thabo Mbeki Foundation was launched in Johannesburg on Sunday 10 October 2010. Speaking at the occasion, Mbeki (2010:2) called for widespread co-operation to realise "the aspirations of the peoples of Africa to rise from the ashes" - a fairly clear reference to the African Renaissance. In actual fact, "African Renaissance" (AR from here on) was not a neologism coined by Mbeki. As Banda (2010:41-50) points out, it is a concept and term with a long history predating Mbeki. Cheru (2002:xii) claims that a Senegalese intellectual, Cheik anta Diop, used the term as far back as in debates around the African quest for self-determination during colonial times. Other Africans, such as the South African Pixley ka Isaka Seme, in a speech at Columbia University in New York in 1906, called for "the regeneration of Africa" - a concept which may be considered a precursor to the call for an AR. The same can be said about the calls of "Africa for the Africans" within the context of the Pan-Africanist movement (Banda 2010:50). In his first address to the Organisation of African Unity in 1994, former President Nelson Mandela called for a process of rebuilding which could later be used by protagonists of the AR to promote their case. He said (quoted in Makgoba 1999:11):

And yet we can say this, that the human civilisation rests on foundations such as the ruins of the African city of Carthage. Its architectural remains, like the pyramids of Egypt, the sculptures of ancient Ghana and Mali and Benin, like the temples of Ethiopia, the Zimbabwe Ruins and the rock paintings of the Kgalagadi in the Namib Desert; all speak of Africa's contribution to the formation of civilization.

Nevertheless, it remains true that Thabo Mbeki played a major role in the upsurge of interest in the concept and the debate around it since 2000. One important indication of the role he played is reflected in the founding of the Centre for African Renaissance Studies at the University of South Africa in Pretoria (Banda 2010:48-49)4. As a result of the prominent role Mr Mbeki played in international politics, especially on the African continent, the call for an AR received great prominence in terms of debates and media attention (cf. Banda 2010:71-72). In the meanwhile Mr Mbeki has been unseated as President of the Republic of SA, and his star has waned. This fact has not brought a complete end to the debate around the AR or some of the institutions which have already been formed to promote the ideal. We are of the opinion that it remains a worthwhile debate which can improve the lot of ordinary Africans. We are equally convinced, though, that the debates thus far and also the implementation of dimensions of the AR which did indeed take place have been characterised by a very important omission. We are, therefore, not going to review the debates which have taken place, or evaluate these dimensions5; but will rather concentrate on this "missing link" (the role of religion) in the life story of the AR debate.

2. The role of religion

Banda (2010:100) notes that, "In the noteworthy academic writings and articles made on the topic of the African renaissance, only but a few discuss it from a religious perspective". He goes on to note the few articles, dissertations and books in which the "missing link" is addressed (:100-101). He emphasises Okumu's comment (2002:261) that in Africa, "Changes in self perception and self-confidence flow from religious and ideological beliefs and are the key to all that follows". We can also refer to the senior African Theologian and Philosopher, John Mbiti's comment (Mbiti (1989:1) that, "Africans are notoriously religious". Parrinder (in Kenzo 2004) had already stated in 1969 that he considered Africans to be "incurably religious". These are not uncontested statements. Platvoet and Van Rinsum (2003:123) do not agree unconditionally with this point of view, and refer to Okot p'Bitek who vigorously opposed Mbiti's contention. The debate is still ongoing today. Kealotswe (in Walsh & Kaufmann 1999:226) emphasizes the reality that most Africans believe that there is a God, "and therefore also believe in a world of spirits impacting the physical realm from time to time"6. This largely agrees with Kalilombe's statement (1994) that the inherent spirituality of African people makes the relationship between the physical and spiritual reality unique. We feel, therefore, that the balance of evidence is weighted in favour of a view which takes religion into account very openly and thoroughly. If we take Mbiti's, Kalilombe's, and others' contention in conjunction with the fact that between 80% and 90% of South African citizens regularly declare in census surveys that they subscribe to some form of organised religion, then we are convinced that one can conclude that religion is a very important fact of life to be taken into account in any social programme or policy. It is therefore certainly at the very least a serious shortcoming that the role of religion in the development, planning and implementation of the AR has not been rigorously analysed and debated as yet.

The three main religious traditions of Africa today are Christianity, Islam and African Traditional Religions. Despite their essential differences, there are also similarities. All three proclaim that human beings, the earth and everything on it have been created by a Creator God, who is generally regarded as the Supreme Being. All three proclaim that the Supreme Being influences events on earth - providing rain and good harvests, determining the lives of human beings, for example by giving them success in certain endeavours, etc. This Supreme Being can be petitioned and placated, especially by making use of intermediaries. So he can and does play a definitive role in our daily lives. Indeed, when misfortune befalls Africans they may, more often than not, ascribe this to the fact that the Supreme Being had been ignored or mistreated in their daily lives. Leaving God and religion out of the equation in Africa, therefore, is far more unacceptable than consciously making the Supreme Being (and the associated spirit world) part of the whole equation (cf. Ban-da 2010:110). For as Mbiti (1970:91) said, "Whatever science may do to prove the existence or non-existence of the spirits, one thing is undeniable, namely that for African peoples the spirits are a reality which must be reckoned with, whether it is a clear, blurred or confused reality". This approach to life enables many Africans to deal with the many fears and insecurities inherent in their daily existence (cf. Keal-otswe (in Walsh & Kaufmann 1999). We would, therefore, argue that the absence of the religious domain in the debates about the AR so far is a serious shortcoming which could indeed lead to the failure of the whole project. It is for this reason that we argue strongly for the inclusion of religion as providing a positive contribution to incarnating dimensions of the AR7. Since we are both Christians, and Christian missiologists at that, we wish to address this religious vacuum specifically from a Christian missiological point of view. We are convinced that it is especially Christian mission which has the potential to nurture Christian involvement in the AR. To this we now turn our attention.

3. The cycle of mission praxis

3.1 Our understanding of mission praxis

In this chapter we intend bringing missionary praxis into dialogue with the concept of the African Renaissance. The purpose of this discussion is to provide meaningful avenues for Christian mission to become intimately involved in the AR. Our understanding of the cycle - or matrix - of missionary praxis has been formed by our involvement in the teaching of Missiology in the Department of Missiology at Unisa. With our colleagues we started developing this methodological approach in preparing a Study Guide for our first year students in the late 1980s (Saayman, 1992; Kritzinger, 1995).

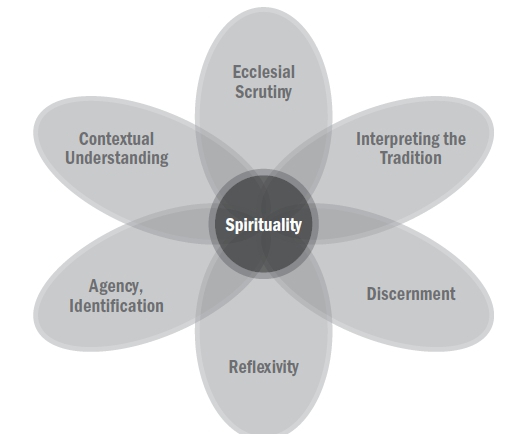

It was a rather elaborate framework which was then simplified under the influence of the four-point "pastoral circle" of Holland and Herriot (1982). Some members of the department then developed it further into a five-point "cycle of missionary praxis" (Karecki 2005)8 and a seven-point "praxis matrix" (Kritzinger 2008), namely, 1) Spirituality (at the centre), 2) Agency, 3) Contextual understanding, 4) Ecclesial scrutiny, 5) Theological interpretation, 6) Strategic planning, and 7) Reflexivity. (Banda 2010:128)

This matrix, which is very helpful both in studying Missiology as well as planning mission outreach, can be presented diagrammatically as a flower with a stamen and petals:

3.1.1 Spirituality

It is our understanding that spirituality lies at the heart of any missionary involvement. When the risen Christ met his disciples on the Sunday evening after his resurrection in order to give them their missionary vocation, he first 'in-spired' (breathed into) them his Holy Spirit (John 20:19-23). And when Jesus of Nazareth proclaimed his own missionary vocation (Luke 4:16-21) in the synagogue at Nazareth, his first claim of authenticity was that the Spirit of the Lord was upon him. Our missionary praxis, therefore, has to be 'in-spired' by our spirituality. There certainly is not only one authentic type of missionary spirituality. For us, spirituality is understood at the heart of our mission praxis as contemplative, sacramental and devotional "faith seeking understanding". This is intimately and indelibly linked to a spirituality which expresses itself in terms of "deeds of justice" in-spired by the Holy Spirit on the basis of our faith-understanding.

3.1.2 Agency

This area of the cycle deals with the person or communities of persons involved in actually carrying out mission. What is their social, economic or class position in society? How do they relate to the receivers of mission, who may be occupying completely different class positions? What is their basic sense of identity in carrying out their missionary vocation?

3.1.3 Contextual understanding

It is very important to enter into mission with a good understanding of the context. How do the agents of mission understand their context: the social, political, economic and cultural factors that influence the situation in which they live and work?

How do they "read the signs of their times", discerning the negative and positive powers at work in their society? What analytical "tools" do they use to do that? Can they articulate their biases and interests, and are they aware how those influence their understanding of the context?

3.1.4 Ecclesial scrutiny

The era of "free-lance" missionaries and evangelists in Africa is long over. Mission outreach must be undertaken in the name and under the auspices of a church. How do the agents of mission assess the past actions of the church(es) in their context? Are they aware of the history of the church(es) and other religious communities in that context and the influence that has on the present situation? How do they relate to the church(es) that are active in that community?

3.1.5 Theological interpretation

The cycle of missionary praxis is, ultimately, a theological enterprise, and therefore all of it must be subjected to careful theological scrutiny. So we have to ask questions such as: How do the agents of mission interpret Scripture and the Christian tradition in their particular context? How do their sense of identity-and-agency, their contextual understanding and their ecclesial scrutiny influence their contextual theology and the shape of their "local" theology of mission?

3.1.6 Strategic planning

It is a generally accepted reality that much of the early mission work, for example in the nineteenth century, was inspired more by an urgent calling than by careful planning. In the world we live in today such an approach is no longer adequate, which gives rise to the need for careful strategic planning. What kind of methods, activities or projects do the agents of mission employ or design in their attempts to erect signs of God's reign in that context? How do they plan and strategise for this purpose? How do they relate to other religious groups and non-governmental organisations that are active in their community? What aims do they pursue - in terms of personal transformation, the "planting" or extension of the church, or the transformation of the society at large?

3.1.7 Reflexivity

It is urgently necessary that any missionary, mission organisation or church should be consciously aware of their mission praxis at all times. This can be achieved by asking questions such as: What is the interplay between the different dimensions of the group's mission praxis? Do the agents of mission succeed in holding together these dimensions of praxis? How do they reflect on their prior experiences and modify their praxis by learning from their mistakes and achievements? How do all the dimensions of praxis relate to each other in these agents of transformation?

4. The African Renaissance and mission praxis

Having described our understanding of the call for an AR as it stands at the moment, and set out our methodological approach (by way of the cycle of missionary praxis), we have to explain in greater detail our understanding of the link between the two.

4.1 4.1 Spirituality

We pointed out above that we understand the role of the Holy Spirit, and therefore of Christian spirituality, to be central to the theory and practice of Christian mission. There is always a type of spirituality (acknowledged or unacknowledged) at work at the heart of all missiological9 action. "Spirituality" here is not necessarily to be equated with "religious experience". It is a force that lies in the 'inner person' or a person's faith system. It nudges and inspires a person to different kinds of actions and reactions. While religions are often primarily based on sets of rules, creeds and rites, spirituality is based more on the inner voice that feeds convictions and subsequent actions. It is also true, though, that religious statutes, creeds and rituals may be needed to form, feed and strengthen different forms of spirituality. In our understanding, spirituality is at the centre of the cycle or matrix of missionary praxis, as a central stream or current that runs through all other dimensions of the matrix. The role of the Holy Spirit and spirituality is also central to the Christian community in Africa - one cannot engage the role of the church unless one engages African spirituality. Prof Allan Anderson of Birmingham University has made that reality clearer than anybody else in his many articles and books, for example Moya (Anderson 1991). We are therefore of the opinion that any discussions about and planning for a phenomenon such as a Renaissance, which is eminently spiritual in nature, will be absolutely in vain if the role and impact of the Spirit is not taken seriously. It is necessary, therefore, that we describe the role of Christian spirituality more fully in relation to the call for an African Renaissance. In order to do so, we find it necessary to distinguish between different types of spirituality10, specifically a spirituality of faith seeking understanding,, and secondly prophetic spirituality (which can also be characterised as spirituality of right action), which should be understood specifically as, "keeping alive the subversive memory of Jesus" (Mortimer Arias). Why this specific choice?

From what we have said above, it is clear that there are many unanswered questions about the proposed African Renaissance. The Christian community in Africa will need much clarification if it is to be wholeheartedly involved in this massive project. African Christians are heirs to the heritage of the entanglement between mission and colonialism in Africa. At the time this mutuality most probably looked very right for mission-minded Christians in the 18th and 19th centuries. As we know, today there are many doubts about the acceptability of the close link which was formed. African Christians should therefore be doubly careful not to fall into such a harmful symbiosis of Christian mission with state-inspired African Renaissance again. So in Christian terms, it will certainly call for a clear "discerning of the spirits" behind aspects of the AR. It is for this reason that Christians will have to be guided by the Spirit in the way of "faith seeking understanding" in co-operating in such a way that Africa can indeed be born anew of the Spirit as a result of this massive undertaking. There are, however, not only many unanswered questions; there are also very many serious obstacles in the way of achieving a renaissance in Africa. Banda (2010:15-40) provides a very sober analysis of most of these obstacles. A very sustained and committed effort will be necessary in order to overcome them, which is why we as Christians will also need a prophetic spirituality to embolden us to identify the problems quite clearly, and to remain committed to our prophetic vision of overcoming them. In our understanding, this has to be in-spired by a spirituality informed by the living memory of Jesus in his mission to announce the beginning of God's reign. Such memory very often in Judaeo-Christian history had to play a subversive role in overcoming the resistance of established institutions and powers to the reign of God (Arias 1984).

4.2 Agency

Human transformation generally does not come about in an ad hoc way or on the basis of the contribution of coincidental charismatic individuals or experiences. One needs proper planning and the longtime commitment of dedicated agents in order to bring about lasting transformation. The same again holds true for Christian mission: as the old saying goes, God could have used the angels to carry out his purpose, but he chose to use human agents. In introducing a Missiological perspective of transformative agency we are going to look at biblical models which, by divine sanction, have been designed to transform societies into positive functional organisms. The so-called 'priesthood of all believers' is one such agency. The office of priesthood in the Hebrew Testament was the privilege of the Levites, but in the New Testament dispensation this privilege has been opened to all Christians. This means that all Christians irrespective of status, gender, age or standard of education may equally serve in the Church towards advancing the reign of God. Thus it is no longer a duty that is reserved for a particular class or family. The Holy Spirit had then begun a new era where 'ordinary people' were given the capacity to serve in accordance with their different talents or gifts. That is why Christian teaching is liberating in many respects. Thoughts of 'entitlement', patronage and nepotism are thus squashed as agency is meant to be service for the communal good by all. This Christian perspective is a necessary thesis when we consider post-independence attitudes in most African societies. In the post-independence era, the spirit of entitlement engulfed many so-called 'war veterans' (in situations where liberation was achieved through war) who considered the 'loot' left by colonial masters (such as powerful and well-remunerated positions) as their rightful due. In South Africa it happened somewhat differently. The politicians who negotiated the "elite pact" which brought about democracy11, seemed to regard it their right to allow the chosen few "deployed cadres" of the ANC through patronage and nepotism to share the 'loot' amongst themselves. Agency in any government-inspired project is, therefore, supposedly first the "right" and "privilege" of only a privileged few. But the practice of transforming mission makes clear that this is a huge misunderstanding, as agency is both a vocation and a privilege of all citizens equally.

The understanding of agency through "the priesthood of all believers" does not negate the necessity of certain specialised agents in carrying out mission, though. For this reason there is, for example, the doctrine of a five-fold ministry in Ephes 4:11-12. They are classified as apostles, prophets, evangelists, ministers and teachers according to the central dimension of the task they have to carry out. The task of the apostles was to lay the foundation for the whole edifice; prophets were supposed to proclaim the will of God in specific situations, especially situations of uncertainty and upheaval; evangelists were the heralds proclaiming God's good news in situations of human "bad news"; ministers had the responsibility to care for those in need, whether spiritual, physical or economic needs; and the teachers were those who had to take care of the proper and specific education of the whole community. This Christian understanding of essential dimensions of human agency can be profitably utilized in the Renaissance project.

One striking element of missionary agencies is their indebtedness to the divine sanctioning. What can this mean to 'human' sanctioned institution such as the African Renaissance? It practically means that because Africans have a strong inclination to the dictates of a Supreme or divine voice, it requires of the proponents of the African Renaissance to search deep both in their souls and consciences in order for them to establish this missing dimension. The African awe for divinity is such that when agency is divinely sanctioned it carries more authority and power. From this vantage point, therefore, the African Renaissance agents can then determine for themselves which type of agency along the nature of the five-fold ministries is appropriate, for what task, time, place and situation. We are convinced that there can possibly arise an enduring agency that exceeds limitations prescribed by human choice, geographic locality and age. However, any agency with all its best intentions that operates without taking the context seriously is bound to experience frustrations and possible failure. Since this is an important Missiological consideration we find it necessary to discuss contextual understanding in the next paragraph.

4.3 Contextual understanding

What can a missiological perspective and praxis contribute to our contextual understanding as to promote an African Renaissance? Africa at the beginning of the 21st century is a diverse, heterogeneous and problematic space (cf Banda 2010:1540). This arises naturally, partly as a result of the legacy left by different colonial systems inherited by various African states (Anglophone, Lusophone, Francophone and Germanic), which were embedded in (sometimes) conflicting economic systems operating in many countries. This has been aggravated as a result of various Cold War political partnerships various countries entered into. Furthermore, fiduciary obligations thrust upon them by their debtors, or as a result of selfish interests of African leaders who entered into questionable dealings with whoever could promise them protection against losing power, influence and riches. Different religious convictions have also played a major role in the divisive history of Africa. For instance, the introduction of Islamic 'Shari 'a' laws in countries such as Nigeria, Sudan and Somalia, has created an atmosphere with a great potential for violent conflict between adherents of various religions. What then could be a political economy that can forge enough consensus and general agreement across the length and breadth of the continent for all to participate equally?

One of the first points to be considered is the contention in theories of transformation that 'one cannot change what one dare not confront'. The political scene in Africa is rife with self-conceited politicians who are prone to high handed methods of dealing with criticism and dissent. The general situation in Africa is that many political leaders have skeletons in their cupboards. Many politicians or governments are guilty of atrocious acts of their own, and are therefore apprehensive of pointing a finger at their counterparts (Banda 2010:162). This sort of behaviour among African political leaders can be called 'Glasshouse-phobia'. It stems from their vulnerability to scrutiny especially by the media. It is self-evident that such leaders will not welcome any peer review mechanism (as proposed by the AR and inherent in Christian leadership) as it looks like an act of 'throwing stones' which might harm their integrity, subsequently harming their 'sovereignty' and their overseas bank balances. As a result African political leaders are loath to reprimand fellow leaders even in cases where churches and NGO's bring clear proof of the abuse of human rights (e.g. in Zimbabwe). The only credible explanation for this conduct is their fear of other leaders criticizing them later in case of similar wrongdoing. Biblical history provides us with many examples where self-righteous leaders were called to order through prophetic action (Banda 2010:131-135). Christianity, therefore, has many precedents on the effectiveness of communities opposing injustice and oppression when relevant bodies are unwilling or unable to do so. Banda (2010:135) refers to Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Rev Frank Chikane and Rev Allen Boesak, as examples hereof. This is why it is so important to keep alive the "subversive memory ofJesus". This is a possible valuable tool with which the establishment and development of an African Renaissance can be promoted.

An overview of the African context (Banda 2010:15-40) has revealed the precarious state of Africa at present. Hostile factors such as war, famine, rape, corruption, and many others, are so endemic that they tend to petrify many activists for justice and democracy (the very people we would need as agents for the AR). Communities which have suffered much violence and war tend to become docile and without hope. The memories of atrocities committed during the war and the actual mental and physical wounds of the victims are enough to create such hopelessness. Sadly, this condition only favours perpetrators who are determined to continue their reign of terror. That is why in post-war countries healing of memories is important. For the AR this would generally be remedial intervention towards restoration and healthy societies. Otherwise many survivors may refuse or be incapable to do anything to engage the current authorities for betterment of the situation of the people. There is, however, a glimmer of hope for Africa. The call for an African Renaissance was in itself this hope the people of Africa cherish and envisage for its success. The political leaders who have enjoined their efforts and resources have as it were created a sense of hope in many parts of Africa. This can be deduced from many articles and a growing number of research work and books since the concept of African Renaissance 'resurfaced' during the presidential era of Mr Mbeki. Several international conferences have been staged on the African soil, emphasising the possibilities for 'rebirth'. Arguably, the crowning glory of these events was the staging of the 2010 FIFA Soccer World Cup in South Africa. These are big steps in boosting the confidence of Africans on their ability to meet the international communities' and fellow human beings' expectations. But they have not yet achieved complete trust. That is why we want to argue further by saying that efforts towards the African Renaissance dream can be handsomely complemented by introducing a spiritual dimension, which we argue is missing in the whole debate of the renewal of Africa. Hope, which apostle Paul espouses together with faith and love, is one of the three core values of the Christian gospel (1 Cor.13:13). Christianity itself is characterised by eschatological hope of the return of Jesus Christ to introduce a new era. The Christian gospel does not proclaim a false and baseless optimism which cannot stand the test of time; it proclaims hope based on a long history of God's faithfulness, love and providence for his people and the earth. By adding the sentiments of the Missiological dimension the growing sense of hope for the realisation of the African Renaissance can be strengthened. In this way a proper understanding of the context, even though it highlights so many problems in Africa, need not necessarily lead to hopelessness and despair. It can, rather, become challenges for a spirituality of right action based on proper understanding.

4.4 Ecclesial understanding

The call for an AR is not only a call for the church to analyse the AR, but especially a call for the church to analyse itself in the light of the AR: is the church ready and able to be a useful instrument or agency in bringing about the AR? The church's primary message, according to the Great Commission, is the Good News of Jesus Christ. This message is liberating and fulfilling in its purpose. But there are divergent opinions as to how this message has or should have been brought home to its recipients under various circumstances and political situations. One clear manifestation of the problem is the ambivalences that exist in mission history in specific contexts. We wish to refer here specifically to the ambivalent role the church played in Africa by taking as an example the church's role in South Africa. This dubious role of the church was heightened especially in the last decades of the rule of the apartheid system ending with the democratic elections in 1994. This situation and the ambivalent role of the church is described clearly by the Kairos Document (Part One) which indicated how different church traditions, in terms of their theological doctrine and racial bias, conducted their praxis and influenced their members under the influence of the socio-political climate of South Africa. The question here is, 'What can this history tell us and how can it help us to steer the African Renaissance dream?' Without doubt the history of the church's duplicitous involvement with undemocratic political systems, as well as its handling of conflicting views, should inform us to be cautious and watchful in our involvement in the AR project. In terms of our understanding of the prophetic vocation of the church, the church is supposed to remain true to Jesus's preferential option for the poor. It is, therefore, the special responsibility of the church to investigate whether the AR is conceived to truly improve the lot of Africa's impoverished and exploited majorities, or whether it is another grandiose scheme to glorify the "strong men" of African governments. And even once the church has decided that the right choice is solidarity with the call for the AR, the church (in the light of its ambivalent past) should always maintain its critical distance from the agents of the AR, co-operating in critical solidarity.

This way of co-operating is required also because church and mission are by design Kingdom oriented. They are called to proclaim the Kingdom or Reign of God which goes beyond denominational boundaries or calls for an AR. Kingdom values are overarching and permeate all spheres of the church's existence. Its ethos is not determined by church law or constitution. It lies in the activity of the Holy Spirit through agents of mission, to fulfill a higher calling that disregards church segregations (Paul vs. Peter12), tradition, culture (circumcision13)or ritual (infant or adult baptism). The Spirit of the Lord operates where oneness of purpose and practice supersedes creed and physical distinction. The African Renaissance needs an overarching philosophy that will help all to have a focal point that supersedes divisive constructs, whether they are abstract or physical; or, conceptual or practical. These should be fostered by the common good for all Africans. They should inspire a sense of accountability towards this common good, engender a protective spirit until it is achieved. Christ protects the vision of salvation through his 'power' (Acts 1:814) and 'presence' (Mat. 28:2015). The African Renaissance movement should protect its vision and dream towards a reborn continent through structures of 'power' and 'presence' in the entirety of the continent. And like the thrust of the Kingdom of God the renaissance structures must be progressive and effective with definite signs of effectiveness (Mark 16:1516).

One of the post-colonial ecclesiastical forces on the African plane to be reckoned with was the emergence of AICs. Arising from a history of suppression by mainline churches, they established themselves despite restriction and even attempts of annihilation by governments colluding with mainline churches. They established a resilient spirituality that did not require a conceptual definition or formal legitimation. All campaigns of indoctrination within formal political, educational and ecclesiastical systems could not deter the resolve of the forerunners of this movement. Until recently, the AICs were the fastest growing church movement in Africa. Their success lied in that the culture and theology they practised appealed to the soul, culture and spirituality of the African majority - it responded to Africans' felt needs. As a church movement they did not try to convert the outlook of the African first before they won the African soul. Their language, approach, and concepts were simple and touched the grassroots. At the centre of the movement there was a thread that runs through all AIC formations which is identical, unmistakable and which binds them together. It is this secret of unity of identity that the African Renaissance movement should strive to discover and emulate. Currently the African Renaissance is enveloped in highly sophisticated17 language of politics, economy and commerce that grassroots people do not understand. The fact is most, if not all, established African Renaissance institutions reside in universities, for example, the Centre for African Renaissance Studies (CARS) at Unisa, and clearly they are inaccessible to the majority of aspiring people. All the African Renaissance vehicles need to learn from the simplicity, accessibility, modelling, packaging and delivery of the AICs. Unless the AR addresses the felt needs (security, housing, water, education, etc.) of African people at the grassroots, and does so in language and concepts that are comprehensible to ordinary African people, it will remain an unachievable pipe dream of a privileged African elite. Here the AICs can teach the thinkers and planners behind the AR a very valuable lesson. Are they willing to learn it?

4.5 Theological interpretation

In this fifth 'petal' of the 'flower matrix' we explore the importance of theological18interpretation. Our premise is that there are many ways of reading the Bible for people of faith. The theological lenses one puts on can therefore determine how one applies God's word in different contexts. It stands to reason that with a long history of doing theology, numerous theological traditions have developed. Some of these theological strands include Roman Catholicism, Lutheranism, Presbyterian-ism19, Methodism, and most recently, Pentecostalism and new charismatic religious movements. It is not within the scope of this chapter to delve into all these theological traditions. Rather, our focus here is to look at the broad theological issues and the consequent impact these differing but legitimate forms of doing theology have on the lives of people and their communities, and in particular, on the African people. It is important to establish this so that one can determine in what possible ways the large African Christian communities can assist in realising the African Renaissance, or where different theological views will have to be accommodated in order to make the Christian community useful to the African Renaissance.

It cannot be denied that most, if not all, theological traditions have over periods of time developed ways to propagate their ideas to other interest groups. One form of propagation has been through the training of agents20. This training, whether formal or informal, lies at the centre of theological interpretation and propagation. Jesus' charge on the apostles to "teach [future believers] these things" (Mt.28:19-22) effectively set the trend by which Christians attempted to obey the obligation to 'pass on' the teachings of Jesus to following generations. We are also aware of the fact that from the Apostolic era, to the era of the Apostolic Fathers, through the era of the Reformation, etc., many divergent teachings crept in initiating the need to 'formalise' the teachings of Jesus in the forms of creeds and doctrines21. These developments help one to realise how propagation of ideas and concepts is important for the survival of a 'movement', in this case Christianity. Not only that, but these concepts were, and still are, formulated into 'schools of thought' that are passed on in the form of discipleship groups among ordinary members or through the ministerial formation for the clergy. The teachings convey specific messages and influence adherents in a particular way in their thinking and doing. In this process, an important abuse started developing. This is the tendency among theologians, preachers, or writers, to develop a simplistic, Biblicist or fundamentalist approach to biblical interpretation, as this interpretation satisfies the felt needs of this specific community at a specific time. The message to be taught is therefore sanctified by claiming that "thus says the Lord", and nobody is allowed to deviate from it. This tendency has been prominent throughout Christian history, and it has also been very prominent in African theological formation, especially within the AICs, which are not organically linked to a broader ecumenical interpretation. It is not surprising therefore to find some African church leaders who want to propagate theological assertions based on what they view as 'the true word of God'. This has caused serious divisions among theological practitioners, with one group accusing another of abusing the Bible or Biblical interpretation for impure motives. In the end stereotypes are created, and other Christian communities are completely exorcised from interhuman relations. If such a sectarian theological interpretation of the AR is allowed to develop, it can only be to the detriment of the whole project. The inclusive wholeness at the heart of the Christian community, verbalized in the concept of "catholicity", has to be consciously promoted. While the AR is propagated and expounded without any reference to the very important religious and spiritual dimension, the danger that such heretical and schismatic expositions are allowed to flourish is extremely real. The serious and urgent need for continent-wide theological consideration of the AR by the influential Christian community is thereby highlighted.

4.6 Strategic planning

In this section we look at the sixth dimension of the matrix that calls for planning with a view to effective action. We wish to concentrate on those programs that are aimed at establishing God's reign in the midst of the people (as we like to interpret the call for an AR from a missiological point of view). The faith community exists as a unique socio-economic entity with definite characteristics (cf Bosch 1991:123-180). In seeking viable modes and models for Africa's development, the renaissance movement needs to utilise the valuable resources available in the church and its subsidiary structures. The church's success in terms of what it has achieved in serving humanity, both believers and unbelievers, cannot be ascribed to its soul-winning activities only. This would be a one-sided and reductionist view and understanding of what the church is and stands for. It is overall activities of the Church, both in word and deed, that have appealed to the minds and hearts of its respondents. Over the ages the church has developed some of these words and actions into effective methods, activities and projects that were duplicated over the years and across the continents. These methods, activities and projects and the planning which brought them into being, are what can be useful in incarnating the call for an AR. This is the more important in the light of the reality that in many areas of Africa laid waste by war, epidemics or famines, the church is the only notable social institution or social formation still present and functioning. Any attempt to plan for an AR, whether through NEPAD, the AU or any other institution, would be shortsighted if it did not make full use of the various planning resources, abilities and expertise of the African Christian community.

In mission the subject of methods (planning) is often paired with the concept of motives. Motives are usually viewed as 'pure' or 'impure'. The motive that stands central to most mission agents in their planning is that given by the Lord, Jesus Christ, namely, 'making disciples (followers)'. This is regarded as a 'pure' motive. This motive to "make disciples" is often incarnated in one of two elements: an evangelistic orientation (concerned with personal witnessing, seeking conversion of everyone to the 'one true faith', and demonstrating strong openness to the Holy Spirit); and an activist orientation (stressing justice and having a critical posture to existing social structures, having openness to involvement in social action, and having openness to confrontation and conflict) (Kritzinger 2008:784). It is these motivational elements of the missionary enterprise which could be useful in the strategic planning for the African Renaissance movement. It is critical that mission and Missiology should meet the African Renaissance movement on this interface of solidarity with humanity and social justice issues.

It can be extremely useful in countering one of the most serious obstacles to an AR: endemic corruption. Governments and the corporate world globally suffer the blemish of corruption and immorality, but it is especially prevalent in African governments and business structures. This is a wide and ingrained problem that cannot be adequately analysed here. What is the church's contribution to countering this problem?

As a point of departure, the church's primary calling is to a 'holy', 'righteous' and 'blameless life' (cf. Gen. 17:122). Its task is also to call all humanity towards this condition and attitude. The church is one of the institutions that still apply what the postmodern worldview sometimes consider to be a 'conservative' and 'outdated' moral code of conduct. But the argument here is not about a 'sinless' and 'blameless' state of the church, but about recognising and accepting sin and its effects as a problem. It is about taking corrective steps by confessing sin, repenting and taking the conversion journey (1 Joh. 1:5-10). To illustrate the complexity of this problem we will use the current government of South Africa as an example. President Jacob Zuma undertook to fight corruption and unethical behaviour. Yet when new ministers took office one of their first actions was to buy themselves very expensive cars. When such expenditure was questioned by social formations, many ministers argued that they had not broken any law. The question, nevertheless, was whether buying a very expensive car could morally be justifiable in the light of serious budget constraints and deteriorating services that are marked by violent protests throughout the country. Moral conscience and moral regeneration23, important pillars of the African Renaissance, require that even if the constitution is silent on a matter, sensitivity to what is morally right should dictate right decisions and actions. Therefore African Renaissance should signal a turnaround from the decay of self-enrichment, inconsiderate use and embezzlement of funds on luxuries. The Christian community, called to a preferential option for the poor, has a special responsibility to highlight this shortcoming in the choices made by politicians.

4.7 Reflexivity

With "reflexivity" we are referring to the responsive interactivity between the different aspects of the praxis cycle. In the previous paragraphs we have discussed six of the seven dimensions of the Missiological praxis cycle. Reflexivity calls for an interplay between the various 'petals' of the flower matrix. Its purpose is to sharpen the value and the integrity of all the elements of the praxis cycle. As a social theory, reflexivity is an interactive relationship of forces that act on each other24. In Mis-siological terms the subject of theory and practice come to mind. As Kritzinger (2010; emphasis ours) says, "we need a more complex and inclusive theological method that brings into focus all the factors that shape religious identity and inter-religious encounter". In this case we are referring specifically to all elements that shape Missiological praxis in the matrix cycle. The African Renaissance approach of neglecting the spiritual dimension in the life of the people on the continent is in effect dismembering parts of the whole. It effectively denies the necessary reflexiv-ity that should prevail between the various parts of the sense-making whole of the African society.

Reflexivity calls for special awareness of the process of contextualization, which has been present in the church since the early days. The task of maintaining the good news as handed down by Jesus and the prophets and the need to apply it to the ever-changing context is what inspires this process. This calls for the need for translating the prophetic messages in Christian tradition and handing them down to next generations. Therefore translation and tradition go hand in hand. The two concepts create a pattern of faithfulness to the notion of contextualisation which Arias thinks should be the norm for the church in any time or any place (Arias 1984:66. Arias laments the fact that the church has unfortunately often upheld a reduced message of Jesus Christ by adhering only to some aspects of his kingdom message. He insists that the Scripture with 'the subversive memory ofJesus' has this thrust of subverting the world and the church itself (:66) and by so doing pointing to the totality of the Kingdom which permeates all aspects of life. Missiological reflexivity is condition of being continually nudged to this realisation of the 'whole' and of being moved as agents of transformation in the hand of God. To achieve this, Arias recognises role of the Holy Spirit as the 'subverter' who was promised by Jesus "to help us to remember" (:67) our mission in the world and time we live in. Arias' concept is helpful particularly when considering the church's challenge to economic, social and political systems under the agency of the African Renaissance. Its role is therefore subversive in that all stakeholders on the continent are drawn towards cooperation. When that is achieved the possibility of a new birth and a new dispensation becomes real.

Reflexivity, therefore calls for interaction between all spiritual, social, economic and political life forces in the African community - any concentration on only one or two of these life forces is reductionistic in nature and doomed to failure. It is a call to the politicians and civil servants driving the AR process, but it is also a call to the church not to be smug in its claim to occupy the moral high ground, but to investigate and analyse its own contribution to the AR anew. We also argue that this reflexivity should be inspired by the subversive and prophetic memory of Jesus; subversive because it seeks a kingdom "not of this world", and prophetic because it reads the signs of the times every day in the light of the eschatological expectation it proclaims. The AR will therefore always be a work in progress, striving for a better and more hopeful future for Africa and all Africans.

5. Conclusion

At the moment most African Renaissance protagonists belong to the intelligentsia, the political and social elites. The African Renaissance call and movement must be popularised (in the sense of made easily accessible and relevant to ordinary people) so that messages about pertinent issues affecting Africans should be conveyed in a language that can spread and take root in the hearts, minds and actions of the common people. People should not remain "consumers" of the idea at the level of trivial matters such as using African Renaissance as a naming activity. The challenge to the African Renaissance movement is relocating many aspects of the movement from the centres of the privileged and the elites to spaces and forms easily accessible to the majority of the people. Exponents of the African Renaissance should move away from leaning in the direction that seems to be establishing it as an "ivory tower" movement, and an exclusive prerogative of the few. The AR can only succeed if it is truly a people's movement, inspired by charismatic leaders. These leaders have a special responsibility to "read the signs of the times" in a "spirit of discernment", which is both predictive and interpretative of the actual events impacting communities at that particular time. When this spirit is operative, affected persons are moved into recognising trends and possible outcomes that may affect specific individuals, leaders, communities or nations. These 'prophets' are then imbued with the necessary charisma to intervene and act in particular ways that suggest, and if heeded, bring solution and relief to the besieged people. Christian missions are embedded in such a 'spirit of discernment' (1 Cor. 2:14). It charges God's prophets to 'sense' the times and warn the people and their leaders of impending dangers. Therefore, God always 'searches' for25and raises these prophets. The church needs to be prayerful and to be 'in touch' with the Spirit of God who is able to impart such gifts to humans. It is our conviction that the proponents of the African Renaissance will need such prophetic figures in their midst and in many African communities to enable favourable conditions for the Renaissance to flourish. African Renaissance activists have to begin to move from theory towards building structures that will impact peoples' lives and nature in a positive and tangible way. In this respect mission praxis can be a useful ally.

In making this claim, we are not calling for a pious "religious salad dressing" to pour over the "hardnosed" political and economical call for an AR (which consist the "real thing"). On the contrary, we are calling for the realistic recognition that the religious realm is (perhaps) the most dominant realm in the lives of African people. Since 1996 South Africa has been constitutionally a secular state - and we are very happy with this state of affairs. The preceding years, when SA was a so-called "Christian state" under the nominally "Christian" apartheid government held no advantages for either the Christian churches or SA citizens. But the fact that we now live in a secular state does not negate the reality that nearly 90% of SA citizens identify themselves as observant adherents of Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Judaism, Buddhism, the African Traditional Religions, etc., in every census. In other words, the religious realm is quite probably the most important realm of human life in (South) Africa. For this reason it makes no sense that the theoreticians and the practitioners of the AR proceed as if an African Renaissance can be achieved without any serious reference to religion in general and Christianity in particular. This is our motivation in offering the present contribution from the praxis of Christian mission as an important adjunct to the realisation of the African Renaissance.

Bibliography

ANDERSON AA 1990. "Umoya": pneumatology from an African perspective. Unpublished M.Ed dissertation. Unisa. [ Links ] [S.l.: s.n.]

ARIAS M 1984 Announcing the reign of God: evangelisation and the subversive memory of Jesus. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

BANDA Z 2010. African Renaissance and missiology: a perspective from mission praxis. Unpublished D Th thesis, Unisa. [ Links ]

CANNON DW 1994. Different ways of Christian prayer, different ways of being Christian: a rationale for some of the differences between Christians. Mid-stream 35:3, pp.309-334. [ Links ]

CHERU F 2002. African Renaissance: roadmaps to the challenge of globalization. Cape Town: David Philip. [ Links ]

GIBELLINI R (ed) 1994. Paths of African Theology. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

KALILOMBE PA 1994. "Spirituality in the African perspective", in Gibellini (ed) Paths of African Theology. Pp. 115-136. [ Links ]

KEALOTSWE ON 1999. "The role of religion in the transformation of Southern African societies", in Walsh & Kaufmann, Religion and social transformation in Southern Africa. pp.225-233 [ Links ]

KENZO MJ 2004. Religion, hybridity, and the construction of reality in postcolonial Africa, in Exchange 33(3):244-268. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, JNJ. 2008. Faith to faith - Missiology as encounterology in Verbum et Ecclesia 29(3):764-790 [ Links ]

MAKGOBA MW (ed) 1999. African Renaissance: the new struggle. Sandton: Mafube Publications. [ Links ]

MBEKI T 2010. "Launch of Thabo Mbeki foundation gives hope", in Pretoria News, 11 October 2010, p.2. [ Links ]

MBITI J 1970. African religions and philosophy. Doubleday: New York. [ Links ]

MBITI JS.1989: African religions and philosophy. Anchor Books: New York [ Links ]

OKUMU WAJ 2002. The African Renaissance: history, significance and strategy. Asmara: Africa World Press Inc. [ Links ]

PLATVOET, J and VAN RINSUM, H 2003. Is Africa incurably religious? Confessing and contesting an invention. Exchange 32:2, pp.123-153. [ Links ]

SAAYMAN W 2008. "The sky is red, so we are going to have fine weather": the Kairos Document and the signs of the time, then and now. Missionalia 36:1, April 2008, pp.16-28. [ Links ]

SAAYMAN W 2010. Missionary or missional? A study in terminology, in Missionalia 38:1, April 2010, pp.5-16. [ Links ]

WALSH T & F KAUFMANN 1999 (eds). Religion and social transformation in Southern Africa. St Paul: Paragon House Publishers. [ Links ]

1 Dr Zuze J Banda is Senior Lecturer of Missiology at the Department of Christian Spirituality, Church History and Missiology at Unisa in Pretoria. He can be contacted at Bandazj@unisa.ac.za

2 The Late Prof Willem Saayman was a Research Fellow and Professor Emeritus of Missiology at the same Department at Unisa in Pretoria.

3 The term "African renaissance" is a contested term. It is used in this article to present an 'institutionalised' move by advocates of Africa's renewal with Mr Mbeki as it's pivotal protagonist. It is must therefore be seen from an all-in-compassing endeavour towards engendering a new discourse of the African hope. Our purpose with this article, though, is focused on the role of religion in the debate; so we are not going to enter into the conceptual debate here. It is extensively discussed in Banda 2010:15-99.

4 See Banda 2010:42-49 for a more extensive debate on Mbeki's role.

5 We refer interested readers to Banda 2010 for an extensive discussion of all aspects.

6 One can refer in this regard to a fascinating incident which happened when the Kariba Dam was built in the Zambezi River (between present-day Zambia and Zimbabwe) in the 1950s. The indigenous residents of the Valley there were the BaTonka people, living on both sides of the river. When they were informed by government officials that they would have to move as a result of the flooding of their places of residences, they initially refused, stating that the River God, Nyaminyami, residing in Kariba Gorge, would not allow the river to be dammed. The builders of the dam (a consortium of some of the best European civil engineering Arms of the time) and the government officials ascribed this opposition to "superstition" (perhaps even "stupid superstition"), and therefore did not take it seriously. But in 1957, as the Kariba Dam was beginning to take shape, a tremendous flood swept down the Zambezi, and all the preliminary works were flooded and heavily damaged, and some white as well as black workers killed. This was a serious setback, but could be explained "scientifically" on the basis of once-in-a-100-year floodlines. So the enigineers started rebuilding. When a second, equally serious, flood swept through just a year later, the government and constructors had a problem. The phenomenon could no longer be "scientifically" explained, and serious resistance was building among the BaTonka. So they chose to send a delegation to discuss events with the BaTonka leaders (making use of the established legal principle of conceding a fact "without prejudicing our rights" - in other words, without conceding that the BaTonka may be right, and the European engineers may be wrong). The BaTonka leaders recommended that a white calf be sacrificed according to tribal traditions in order to appease Nyaminyami. This was done, and legend has it that the next day the bodies of the dead workers were found floating at the exact place where the calf was sacrificed, and the construction went ahead without further problems. We do not recount this episode to make fun of "stupid African superstitions"; neither do we wish to claim that this "proves" the existence of Nyaminyami and the efficacy of animal sacrifice. We rather wish to highlight the fact that even the best skills and expertise which European construction Arms could muster at the time, had to take cognizance of the impact spiritual forces have from time to time on the physical realm in Africa. (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nyaminyami, acc. 14/07/2009). This incident is recorded not only in wikipedia, but also in academic papers and government reports. So we do not encourage AR leaders to initiate every project with an animal sacrifice; we encourage them to take the spiritual and religious realms of the life of African people much more seriously than they have done thus far.

7 See Banda 2010:105-110 for a more extensive argument about the importance of religion in the debate.

8 The five points are: Insertion, Context Analysis, Theological Interpretation, Planning and, at the centre, Spirituality

9 We are aware of the debate relating to the preferential use of the following terms over against each other, namely, missionary, missional, missiological and mission. Our attitude and approach in this regard is integrational and not reductionist. See Saayman 2010 for a terminological explanation.

10 Cannon (1994:321) distinguishes six different types of spirituality; we utilize two of them.

11 For a discussion on the concept "elite pact" for the 1994 agreement, see Saayman 2008:22.

12 Gal. 2:14 When I saw that they were not acting in line with the truth of the gospel, I said to Peter in front of them all, "You are a Jew, yet you live like a Gentile and not like a Jew. How is it, then, that you force Gentiles to follow Jewish customs?

13 Gal. 5:2 Mark my words! I, Paul, tell you that if you let yourselves be circumcised, Christ will be of no value to you at all.

14 Acts 1:8 But you will receive power when the Holy Spirit comes on you

15 Mt 28:20 ... And surely I am with you always, to the very end of the age."

16 Mk 16:15 and the Lord worked with them and confirmed his word by the signs that accompanied it.

17 A good example of 'sophistication' was the initial method of acquiring Soccer World Cup tickets, through internet and bank applications. When that was modified to the 'over-the-counter' method used in local matches, tickets began to sell like hot-cakes sending Fifa computers crashing because of the influx.

18 We take this to be a second step after the simple acceptance in faith of the Christian message.

19 We include hereunder the broader Reformed Traditions such as Calvinism.

20 Agents embraces a variety of those send, e.g. missionaries, activts for peace, transformations, etc.

21 For example, the Apostle's Creed and the Doctrine of the Trinity.

22 Gen. 17:1 "I am God Almighty; walk before me and be blameless.

23 President Zuma was himself the founder member of the Moral Regeneration Movement while he was Deputy President during the term of former President Mandela.

24 An example is 'bidirectional relationship' between cause and effect, such that people tend to act causing reaction or they themselves react to external stimuli (cf. Wikipedia/reflexivity accessed 20/5/2010).

25 Ezek 22:30 "I looked for a man among them who would build up the wall and stand before me in the gap on behalf of the land so that I would not have to destroy it, but I found none.