Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Missionalia

versão On-line ISSN 2312-878X

versão impressa ISSN 0256-9507

Missionalia (Online) vol.41 no.2 Pretoria Ago. 2013

Resonance at Rutba: The relevance of New Monasticism for South Africa1

Carl I. Brook2

ABSTRACT

As secularism entrenches itself in a still-new South Africa, alternative ecclesial forms will continue to spark interest among people looking for renewal within - and without -the church. The promise of one such form, the 'new monasticism,' merits study not only because of its predecessor's responses under historical empires but also due to its present moment under the Empire of state capitalism.

Following some discussions on context, the article explores the movement from a missional perspective: its Anabaptist antecedents, its lay-monastic heritage and North American origin. Two concrete examples are described, with cultural commentary. The remainder of the article questions the movement's relevance for South Africa, evaluating some of the conditions conducive to its local establishment. Despite a negative assessment hope is nonetheless held out for intentional Christian communities, primarily in respect of their visibility.

Keywords: church and state, community, economics, GEAR, morality, new monasticism, RDP

Introduction

After the gang-rape, disembowelment and murder of two young women -Jyoti Pandey and Anene Booysen - made headlines in 2013, I was struck by the different responses of the various governments to these atrocities. In both nations, there were ongoing riots at the time: in country A, protestors were demanding security for women; in country B, protestors were demanding a minimum wage. In country A, the prime minister of a nation of one billion stood at the airport to receive the coffin of the rape victim; in country B, a presidential statement of condemnation was issued. No prizes for guessing which nation was which!

The president's statement read: "The whole nation is outraged at this extreme violation and destruction of a young human life." My question, articulated in a Sunday sermon at the church where I worship with, was: "Just how outraged are we?" Many things outrage South African Christians: potholes in the road, fuel prices, utility interruptions, even - may God forbid - tolled highways. Rape, it seems, is not one of them. The victim has to be very old or very young, or involve multiple participants, for the story to make headlines.

The subject of the sermon - rape - shocked a congregation whose ears were too refined for such indelicate matters. Despite our grumbling about an incompetent police-force and lenient judiciary, we would rather let those authorities deal with the issue than engage with and process it ourselves as the Church, as disciples with a socially-responsible conscience and a public witness to our faith. Thus are we perceived to be so heavenly-minded that we are no earthly good. Thus is the church invisible.

Context

The restoration of the church will surely come from a new kind of monasticism, which will have nothing in common with the old but a life of uncompromising adherence to the Sermon on the Mount in imitation of Christ. I believe the time has come to rally people together for this (Bethge 2000:462).

Bonhoeffer's assertion, articulated in a letter to his agnostic brother in 1935, is claimed by many new monastics3 today as prescient regarding the need for fresh expressions of an ancient tradition. "What Bonhoeffer, now famously, said in that letter was to prove both prophetic and affirming to that which it predicted ... within twenty-five years of his own martyrdom at the hands of the Nazis, a new monasticism was aborning all over western Christendom" (P. Tickle, in Dekar 2008: ix).

Whether the statement may be considered a legitimate departure point for the movement or not is considered elsewhere (Brook 2011). What concerns us here is its relevance beyond Europe and North America. What would an alternative monasticism offer a rapidly secularising South Africa? "A flight to the desert" may be the cynical rejoinder but, as we shall see, metaphorically correct. Location is a key issue in the new monasticism. Regarding the state of secular morality, Alasdair MacIntyre writes:

What matters at this stage is the construction of local forms of community within which civility and the intellectual and moral life can be sustained through the new dark ages which are already upon us. And if the tradition of the virtues was able to survive the horrors of the last dark ages, we are not entirely without grounds for hope. This time, however, the barbarians are not waiting beyond the frontiers; they have already been among us for quite some time. And it is our lack of consciousness of this that constitutes part of our predicament. We are waiting not for Godot, but for another - doubtless very different - St. Benedict (1981:245).

MacIntyre's analysis of western moral discourse shows how the development of 'virtue' cannot be separated from its communal context. Key to his thesis is a recognition of that moment in Western society when "men and women of good will turned aside from the task of shoring up the Roman imperium and ceased to identify the continuation of civility and moral community with the maintenance of that imperium" (1981:244). A critical issue, therefore, is the church's relationship with the imperium or state - or, as new monastics put it, with 'empire'. For new monastic communities, "relocation to the abandoned places of Empire" (McKenna 2005) is a basic tenet of self-understanding. What does that mean in South Africa today? Where are our 'abandoned places?'

"A mission to the West must be countercultural, though not in an escapist way." surmised David Bosch. "I believe that we have to communicate an alternative culture to our contemporaries. Part of our mission will be to challenge the hedonism around us, inculcating something of the spirit of being 'resident aliens' in the world" (1995:56f.). This quote refers to a title by Stanley Hauerwas and William Willimon, Resident Aliens, in which churches are challenged to develop Christian life and community rather than trying to reform secular culture (cf. shoring up the imperium). Hauerwas' ecclesiology has gained currency among new monastics and may help explain why they, while arguably anti-establishment, are not anti-church. As Wilson-Hartgrove points out,

The 'new' in new monasticism is closely tied to the 'new' of new creation. The new monasticism may be distinguished from the Christian communitarian movements of the 60's and 70's in that it is self-consciously committed to the church (not rejecting it) and tied to tradition (not 'new' in the sense of novel) (2004:18).

Of course, 'new' monasticism can technically describe any development within the monastic tradition; for example, the Cluniac reforms of the tenth and eleventh centuries. It is in its modern sense, however, that the term is used: that is, contemporary intentional communities4 drawing on classic monastic tradition. On the other hand, inasmuch as we are engaging a renewed monasticism (that is, a movement within Christianity) this enquiry cannot be described as contributing to the study of 'new' religious movements (NRMs) - monasticism is an ancient tradition. Or has it generated enough independent momentum to be regarded as such? According to Encyclopaedia Britannica, NRMs are 'new' because they offer innovative religious responses to the conditions of the modern world, despite the fact that most NRMs represent themselves as rooted in ancient traditions. NRMs are also usually regarded as 'countercultural': that is, they are perceived (by others and by themselves) to be alternatives to the mainstream religions of Western society, especially Christianity in its normative forms.5

This definition is descriptive of the new monasticism.

Antecedents

Since the time of Luther, Protestantism has been noted for its repudiation of classical monasticism. Yet, in the centuries following the Reformation, the impulse towards intentional community - and even monastic community -has been evident among various ecclesial movements. The Anabaptists, for example, endeavoured fully to live up to the ethical demands of the Sermon on the Mount. The Catholic way of striving for Christian perfection was that of the monastery, communities of celibates apart from the world. The Anabaptists were akin to monks in seeking perfection in communities separate from the world, but, unlike the monks, they married (Latourette 1953:779).

The Anabaptist view of the church as "a visible fellowship of obedient disciples, exhibiting the way of suffering love" was markedly different from that of the Reformers. Anabaptists saw the church variously "as congregation, as inner spiritual reality, as intentional community and as kingdom of God. However, at the centre was the idea of the church as a believers' fellowship (Gemeinde) versus the church as a state church (Volkskirche)" (Loewen 1988:18). Monastic elements are evident in the lifestyle of the Hutterites, who practise, amongst others, thecommunity of goods. In their membership ceremony, "the novice would have one last look at all the possessions she or he had brought to community. The material goods were placed on one side of the room, and the community members on the other. One last look - a final choice" (Janzen 2005:92). Latourette sees in these Anabaptist groups:

manifestations of a continuing strain in Christianity which had been present from the very beginning and which before and since the Reformation has expressed itself in many forms. It was seen in the Christians of the first century who, impressed by the wickedness of the world, sought so far as possible to withdraw from it and live in it as distinct communities but not to be of it (1953:786).

Ivan Kauffman argues that this 'intentional' impulse predated monasticism, citing groups such as the charismatic Montanists who were committed to lay discipleship and who, far from withdrawing from society, bore messages "intended for the poor and marginalised" (2009: 112). It is the tension between monastic 'withdrawal' and intentional 'engagement' that has shaped the new monasticism.

Intentional community was important to Von Zinzendorf who, with Moravian refugees, founded the village of Herrnhut on his land. While spending a few days at Herrnhut, John Wesley learned some of the methods later introduced to Methodism. For example, "after the Moravian pattern, the societies were at first divided into 'bands' to aid their members in the nourishment of the Christian life" (Latourette 1953:1026). Wilson-Hartgrove observes that present-day United Methodists "have come to understand that Methodism itself consists of many 'monastic' practices that arose in England during a time when monasticism was officially illegal. Wesley's class system and cell groups, then, can be read as monastic disciplines" (2004:2).

Paul Dekar notes "three signs that we are in a period of renewed monastic spirituality" (2008:16). These are, firstly, the growth of lay associations permeating the barrier separating monastery from world. Regarding monasticism as a 'yes' to the world, Thomas Merton saw the importance of contemplation for ordinary people.

The most significant development of the contemplative life 'in the world' is the growth of small groups of men and women who live in every way like the laypeople around them, except for the fact that they are dedicated to God and focus all their life of work and poverty upon a contemplative centre (2003:142).

This phenomenon is noted in the rising number of oblates, lay people (single or married) who seek to live by a Rule in association with a specific monastic community (cf. James 2008) for example, a Franciscan associated with a Cistercian monastery. At the 2004 new monasticism gathering referred to below, it was evident that significant parallels existed between lay and the new monasticism.

Though apparently dominated by those of Protestant background, a number of those from the Catholic tradition noted the wisdom of the post-Vatican II church in recognizing 'ecclesial lay movements' as potential works of the Spirit and have greatly encouraged them as they are left to control and limit themselves. Examples of these ecclesial movements include San Egidio, Communion and Liberation, Focolare, the Charismatic movement and the Neo-Catechumenate (Houston Catholic Worker 2004).

Another sign, writes Dekar, is the vigour of Protestant monasticism. Notwithstanding the Reformers' antipathy, some Protestants do not see faith and monasticism as mutually exclusive. While maintaining their Reformed convictions, these people are attracted to a Catholic-type spirituality. As Michael Green observes:

What I mean is much more far-reaching... than the Roman Catholics. I mean the renewed interest in liturgy: alternative prayer books, the influence of Taizé, the rediscovery of the Eucharist as the central and main service on a Sunday, and the astonishing hunger for retreats. I mean, too, the steady move towards a Catholic form of spirituality among large numbers of Christians who began their pilgrimage as Evangelicals (1994:4).

Dekar's third sign is the emergence of the new monasticism.

The new monasticism

MacIntyre's suggestion regarding the moral state of western civilization, that Christians need to construct 'local forms of community' that can support the tradition of the virtues, provided the foundation to another philosopher's work: Living faithfully in a fragmented world, by Jonathan Wilson (1998 T&T Clark). "Waiting for another Benedict," Wilson reasoned, is a call for a new monasticism. In 2004 he wrote the introduction to School(s) for Conversion, a remarkable document incorporating the fruit of a critical discussion concerning the construction of 'local forms of community'. This gathering, which some believe "officially marks the birth of the new monasticism" (Moll 2005:2), was convened by Wilson's son-in-law, Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove. It took place in June 2004 in the city of Durham, North Carolina, and was occasioned thus:

I and my community at the Rutba House called together a group of Catholics, Anabaptists, Mainliners, and evangelicals to discuss ways in which their lives could be understood as a neo-monastic movement. We did not give them definite guidelines about what to discuss, but rather presented them with the challenges that face the church and world today: economic, political, social, sexual, and ecological (Wilson-Hartgrove 2004:1).

At the meeting, Wilson outlined some of the questions he grappled with in living faithfully, including: what does the new monasticism add to renewal movements that already exist in the church? What are the forms in which the new monasticism is taking shape? What is the new monasticism's relationship to the rest of the church? In partial response, Wilson's introduction to School(s) for Conversion suggests three guiding convictions for the movement's witness (Rutba House 2005:3ff.). The new monasticism is to be:

(a) historically-situated. That is, shaped by strategic and tactical responses to its particular historical situations. In order to fulfil its telos, Finkenwalde6 was located away from the centre of power (Berlin); by the same token, the Sojourners community had to move to the centre of power (Washington, DC). The historical situation of new monasticism is informed by the influence of Empire.

(b) eschatologically directed. "Since one of the marks of our cultural moment is the loss of any sense of telos and the consequent reduction of all action to the battle for power over the other, the recovery of teleological thinking and living is one ... critical task of the day." Living eschatologically resists the temptations intentional communities face to either exist only for themselves, or only for the world.

(c) grace dependent. New monasticism is particularly susceptible to the temptation of heroism. 'Disciplines of grace' such as mundane tasks and spiritual disciplines resist this temptation by reminding community members of their dependence on each other and on God. In Life Together, Bonhoeffer warned against illusory ideas (the 'wish dream') that even serious Christians can bring to community (1954:26).

In this diverse group, then, "not unified by a shared theological tradition, or denomination, but by the wisdom of a shared legacy, and a vision of a spirituality that can shape the Christian life in post-modern society" (Dekar 2008:5), the following characteristics or 'marks' of a new monasticism were conceived:

• Relocation to the abandoned places of Empire.

• Sharing economic resources with fellow community members and the needy among us.

• Hospitality to the stranger.

• Lament for racial divisions within the church and our communities combined with the active pursuit of a just reconciliation.

• Humble submission to Christ's body, the church.

• Intentional formation in the way of Christ and the rule of the community along the lines of the old novitiate.

• Nurturing common life among members of intentional community.

• Support for celibate singles alongside monogamous married couples and their children.

• Geographical proximity to community members who share a common rule of life.

• Care for the plot of God's earth given to us along with support of our local economies.

• Peacemaking in the midst of violence and conflict resolution within communities along the lines of Matt 18.

• Commitment to a disciplined contemplative life (Rutba House 2005).

For a commentary on these Marks, the reader is referred to School(s) for conversion published by Rutba House. This intentional community is itself established in an 'abandoned place,' an economically depressed quarter of Durham city. In an area from which many are trying to escape, the witness of a living community countering the pull of the suburbs speaks more powerfully than words. Another well-known example of the new monasticism is The Simple Way directed by Shane Claiborne and located in "Pennsylvania's poorest neighbourhood" (Moll 2005:3). In their evangelical desire to challenge racial and class divisions, Rutba House and The Simple Way have not taken typically Protestant forms. They represent, rather, a more ancient kind of faith-community. Moll sees these movements as the latest wave of evangelicals who see in community life an answer to society's materialism and the church's complacency toward it. Rather than enjoy the benefits of middle-class life, these suburban evangelicals choose to move in with the poor. Though many of the same forces drive them as did earlier generations - a desire to experience intense community and to challenge contented evangelicalism - they are turning to an ancient tradition to provide the spiritual sustenance for their ministries (2005:1).

Another writer describes the movement as a 'new take' on an old tradition by contemporary communities who think the church in the United States has too easily accommodated itself to the consumerist and imperialist values of the culture. Living in the corners of the American empire, they hope to be a harbinger of a new and radically different form of Christian practice. These 'new monastics' pursue the ancient triumvirate of poverty, chastity and obedience, but with a twist. Their communities include married people whose pledge to chastity is understood as a commitment to marital fidelity. Poverty means eschewing typical middle-class economic climbing but not total indigence - some economic resources are necessary for building this desert kingdom. Obedience means accountability not to an abbot but to Jesus and to the community (Byassee 2005:1).

Part of the new 'twist' is an appreciation of technology. "These communities' eager use of the Internet reveals some of what is new in the new monasticism. They do not reject technology as such. They embrace the Internet, as it serves their purposes of linking similar Christian communities to one another and sharing resources" (:2).

Naturally, the new movement is not without its critics. We mention two reservations linked to the 'Twelve Marks'. Anthony Grimley has echoed the concern of mark #5, submission to the church:

There is a danger that new monasticism is being developed into a leisure activity and a facility for people to use in their despondency with Church . An effect that a pick and mix society is having on new monasticism is a manipulation of traditional monastic values and spirituality in order to clean, refresh and re-package monasticism to make it easier to live with and more socially acceptable (2008).

Another criticism of new monasticism is its lack of ethnic diversity. The challenge of transcending racial and class divisions was mentioned in mark #4 above. Despite their enthusiastic involvement in poorer communities, new monastics are typically "young and white and single" (Anderson 2007:2). In this regard, the following example is equally pertinent in South Africa:

One of the Sojourners' original goals was to serve some of the tens of thousands of refugees displaced to San Francisco as a result of the civil war in El Salvador. Three Salvadoran families joined the church and benefited from its legal clinic and job preparation aid. As soon as they acquired the resources, the families promptly bought minivans, left the church and moved to the suburbs. Perhaps those who have less of a chance at pursuing the American dream are not yet ready to be disenchanted with it (Byassee 2005:5).

Is this dissatisfaction with the American dream the prerogative of whites only? In this country, where the 'South African dream' is threatened by the hegemony of Empire economics, the question is a vital one, underlining the relevance of the new monasticism.

Local relevance

Among our population's different economic strata, three major groups of approximately 15 million people each can be identified (Visser 2004:14). In terms of total income received, the data are as follows:

• 88% received by about 4 million whites and 11 million blacks

• 8% received mainly by blacks (about 15 million)

• 4% received mainly by blacks (about 15 million)

Visser's statistics, now ten-years-old, reported 43% of South Africa's population as unemployed and indigent. With a current unemployment rate hovering at 25%, it is difficult to draw social parallels between our economic situation and those of more developed economies. Nevertheless, is there any overlap with conditions which stimulated the rise of new monasticism in Europe and America? If so, can we expect the formation of similar monastic communities?

The questions are complex, bound up with the ongoing development of South African society. Research on the history of local intentional communities is the subject of another thesis, but it is certainly fair to ask concerning the relevance of new monasticism in this country. It is my contention that the new monasticism (at least that advocated by the 'Twelve Marks') is not readily transferable. That is, South Africa does not share some of the conditions key to the conception of the movement as practised in Europe and North America. These conditions include:

Political: We have already touched on the idea of 'empire,' the first Mark and touchstone of the new monasticism. In keeping with early monasticism, the new monastic view of the state is decidedly negative. Following MacIntyre's analysis of Western morality, new monastics are profoundly sceptical regarding government's ability to sustain 'the virtues'. The movement is away from centralised power, with its attendant potential for corruption, and towards the margins inhabited by the powerless.

By contrast, for several years at least, the new post-apartheid government's approach to society's powerless was marked by a commitment to the poor - a commitment that secured a 'critical solidarity' from the church. However, as this commitment degraded - evidenced by an increase in graft and a plethora of service-delivery protests - so 'solidarity' has reverted to critical 'engagement.' This significant shift will be examined below.

Economic: Commensurate with the wealth accruing to societies in the developed world is a Western disillusionment regarding the 'rewards' of economic empowerment. As discussed under the fourth Mark, Lament for Racial Divisions, whites and blacks are often on different economic trajectories: some are moving from capital, others towards it.

In South Africa, a heritage of political disenfranchisement has necessarily induced the latter. Where the vast majority are moving towards financial capital, the idea of intentional poverty (or even simple living) is alien. To repeat Byassee: 'Perhaps those who have less of a chance at pursuing the American dream are not yet ready to be disenchanted with it.' Insofar as that dream still enchants most South Africans, new monastic communities will struggle to take root.

Theological: The Kairos Document's 1985 call to churches on the side of the oppressor or "sitting on the fence" to "cross over to the other side to be united in faith and action with those who are oppressed" had the convenient effect of categorising denominations according to their response to the Struggle. As one churchman put it, "Apartheid may well have ended at least a decade earlier had it not been for so many cowards in the pulpit" (Storey 2012: 9) and, indeed, the solidarity of many mainline churches with the liberation cause became the basis for their 'critical solidarity' with the state's initial development program, the RDP.

Another theological stance represented by a large sector of local churches, and one echoing the previous point on economic trajectories, is the 'health and wealth' teaching espoused by many Charismatics. If the amount of television airtime propagating prosperity theology is any measure to go by, there must be large numbers of adherents. In a 2006 Pew ten-nation poll of 'renewalists' (Pew 2006), participants were asked if God would "grant material prosperity to all believers who have enough faith." 91% of South African Pentecostals and 79% of South African Charismatics said yes.

A third stance is the passive acquiescence to the status-quo commonly adopted by apolitical congregations with a privatised faith (cf. Kretzschmar 1998). This includes many African Indigenous Churches (AICs) for whom the weaknesses of communalism sometimes outweigh their strengths (Kretzschmar 2008:85-89). It is not within the purview of this study to assess the social policies of South Africa's denominations; suffice it to say that, among such established theological stances, there appeared to be little room for the interrogation of church-state relations. 'Critical solidarity' consisted of "more solidarity than critique. Indeed, there were times when the relationship looked more like co-option" (Storey 2012:13).

For these reasons, then, it is not surprising that a ground swell of intentionality resulting in new monastic communities has not taken off. True, an increase of interest in Catholic spirituality is manifest in a growing retreat movement (cf. Jenkins, Schutte). But political, economic and theological conditions in the United States are generally not true of this country. Of course, insofar as the Twelve Marks do not define contemporary monasticism, intentional communities may well assume their own local flavour and chart their own manifesto. This may well be the case in a South Africa where Caesar has, apparently, forgotten the virtues necessary for moral regeneration.

The amnesia was rapid. After a successful strategy of resistance, the South African Council of Churches adopted a new attitude towards the state, that of 'critical solidarity.' Reconstruction, said Charles Villa-Vicencio, would involve theological wisdom and contextual decision-making:

Utopian visions created by prophets, preachers and poets are important ingredients in the process of reconstruction. Ultimately, however, these visions need to be translated into societal practice and laws operative in the here and now. This practice and these laws will necessarily fall short of the projected vision, but must provide the basis and vision for the long walk to social and economic freedom beyond political liberation (quoted in Carmichael 1996:185).

The secular vision of a new South African society was summed up in the Reconstruction and Development Programme. Rather than watch from the side-lines, the Church's active support was strongly encouraged:

• Liz Carmichael called for a spirituality of reconstruction that sought to be "a channel of God's work in the context of these immense needs. The work entails a co-operative effort to restore and develop persons and community . The spirituality that underpins it must combine fundamental values with the practical skills of development" (1996:191). She went on to suggest that such a spirituality calls for two poles: one of silence, the other of involvement with people - a theme developed by Trevor Hudson. Aligned to these poles might be developed a kind of active retreat, 'pilgrimages of pain and hope', in which people mainly from a more affluent background enter into an eight-day reflective encounter with suffering and with people who, amid the suffering, 'refuse to become prisoners of hopelessness ...Encountering these 'signs of hope' challenges the pilgrims to examine their own faith-responses within the present historical moment (Hudson 1995:92).

• Another element of 'reconstruction spirituality' was service in solidarity of others, of critical importance for South Africa at this time of when many (especially but not only whites) who have been privileged with a good education and training are tempted to withdraw from public responsibility and pursue goals of self-interest (de Gruchy 1997:361). Since then, depending on one's outlook, the implementation of affirmative action policies have either undermined or reinforced de Gruchy's implicit invitation.

• Still another element was confession of guilt. Offered on behalf of the Dutch Reformed church by Willie Jonker at the 1990 Rustenburg Conference, this controversial instance "opened up a new dynamic at the Conference, pointed the way beyond the impasse of the past, and led to further reflection on the extent of the church's guilt in South Africa" (de Gruchy 1997:362). The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) is an example of how the state persuaded South Africans to deal with their past, appointing a church leader (rather than, for example, a civil judge) as the commission's chairperson. Thus was a strong Church voice partly muted (Storey 2012:15)

This collaboration between church and state, this 'critical solidarity,' this 'vision being translated into law,' this 'co-operative effort' and 'underpinning' spirituality entrenched the RDP as a vision guiding both church and Empire for the benefit of all - as Desmond Tutu put it - 'the rainbow people of God.' With respect to this colourful analogy, how visible was the church in such an alliance? How distinctive could it have been? Many of the societal crises which preoccupied the press seemed not to raise the ire of a church whose voice had grown strangely silent.

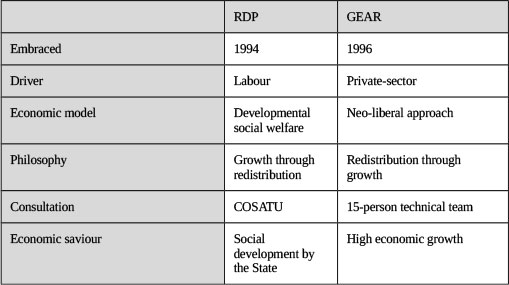

The adoption of GEAR ('Growth, Employment and Redistribution') represented a sea-change in the State's macro-economic strategy. The admittedly simplistic table below summarises the salient differences described in Visser 2004.

Whereas the RDP suffered from a lack of capacity, poor service-delivery and job-creation, GEAR was criticised for being "anti-development" and "openly Thatcherite." (Sources?) Perhaps due to an economic growth-rate less than half that expected, between 1996 and 2001 "employment shrank instead of growing by 3%. Instead of the additional 1.3 million job opportunities supposed to be created by 2001, more than 1 million jobs have been destroyed since 1996" (: 10). By 2003, "in the light of worsening poverty and the lack of social delivery" South Africa was, according to Patrick Bond, "a socio-economic time bomb" (:12).

Ten years later, while the bomb has not yet exploded, the tight Church-State relationship has cooled decidedly. The complaint issued by the National Church Leaders' Consultation protesting ANC interference in October 2011, and Archbishop Makgoba's 2011 open letter to President Zuma protesting the Protection of State Information Bill are 'signs of hope .churches are reasserting their separate and prophetic role, however gently" (Storey 2012:19). The question 'most important to God,' Storey suggests, is not whether a particular Caesar is democratically elected (as if that provides insulation from critique), but whether any actions of today's democratically elected Caesar impact destructively or harmfully or violently upon those, especially the most marginalised, who bear the Imagio Dei. If so, they must be critiqued, challenged and countered by the church (:13).

It is in this regard that intentional communities can help Christians, perhaps disaffected with traditional church responses, to grapple with the contemporary issues of our time. Unlike traditional monastics, there is a public face to their devotion. Their emphasis on community and solidarity with the powerless establish them as the church visible, while living 'monastically' on the margins. In the visibility of the church, Hauerwas sees "the signs of a turning away from Constantinianism, for in its visibility the church must distinguish itself from the state' (Richardson 2007:115). Guided by a communal wisdom in line with their peculiar telos, new monastics regard both church and state with their programs critically. They challenge the established church: Power tends to corrupt! Where is your prophetic critique? Good critique requires critical distance!

Conclusion

It is fair to say that the establishment of ecumenical communities in the twentieth century by Protestants with a Catholic-style spirituality has broken across religious stereotypes. Wilson's criteria for the new monasticism, that it be 'historically situated', 'eschatologically directed', and 'grace-dependent', are relevant for South Africa as much as any other nation - they are the 'where,' 'what' and 'how' of intentional community. The question remains, however, whether St. Benedict would wish to 'save' Western civilisation at all. For, in South Africa at least, America's idols are fast becoming our own.

Revisiting Bonhoeffer's assertion earlier in the article, a 'new' monasticism was called for, not because the 'old' had nothing to offer, but because the church needed a political re-establishment. This was a key ingredient lacking in traditional monasticism. A political self-awareness, invigorated by spiritual disciplines, would constitute the vitality needed to restore the church.

In the post-modern era of liberal democracy, particularly those with a strong welfare programme, the picture is not as sharply defined. The identity of Empire is interpreted variously from group to group. Perhaps it is narrow-minded to speak of state power, when corporations and even labour unions wield enormous influence. For Bonhoeffer and the new monasticism, the restored church will position itself specifically with regard to power. Reflecting on the church's public vocation, Rasmussen writes:

An eschatological community of the cross moves, like Jesus, to those places in society where the mortal flaws of human community are most obvious. There it takes up its ministry, as participation in God's suffering with and for others. Almost by definition those are the abandoned places of the forgotten, powerless, exiled or poor. By definition, then, the community of the cross looks for salvation where the wider public normally does not look (1990:85).

References

Andersen, J. 2007. 'A carnival for Christ' in Sojourners Magazine (January 2007), 2. http://www.sojo.net/index.cfm?action=magazine. article&issue=soj0701&article=070122 Accessed November 2012. [ Links ]

Bethge, E. 2000. Dietrich Bonhoeffer: a biography. (Revised and edited by Victoria Barnett.) Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Bonhoeffer, D. 1954. Life together. New York: Harper Collins Publishers. [ Links ]

Bosch, D.J. 1995. Believing in the future: toward a missiology of western culture. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Trinity Press International. [ Links ]

Byassee, J. 2005. 'The new monastics: alternative Christian communities' in The Christian Century (18 October 2005). http://www.christiancentury.org/article.lasso?id=1399 Accessed November 2012 but now only available by subscription. [ Links ]

Carmichael, E.D.H. 1996. 'Creating newness: the spirituality of reconstruction' in Archbishop Tutu: prophetic witness in South Africa. Cape Town: Human & Rousseau. [ Links ]

de Gruchy, J.W. 1997. 'The reception of Bonhoeffer in South Africa' in Bonhoeffer for a new day: theology in a time of transition. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Dekar, P.R. 2008. Community of the transfiguration: the journey of a new monastic community. Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books. [ Links ]

Green, M. and Stevens, R.P. 1994. New Testament spirituality. Guildford, Surrey: Eagle. [ Links ]

Grimley, A. 2008. 25 years of new monasticism. http://www.monos.org.uk/images/file/New%20Monasticism(1).pdf Accessed November 2009, no longer extant. [ Links ]

Houston Catholic Worker. 2004. 'The new lay monasticism: schools for conversion' in Houston Catholic Worker, Vol. XXIV No. 5, September-October. http://cjd.org/2004/10/01/new-lay-monasticism-schools-for-conversion/ Accessed October 2012. [ Links ]

Hudson, T. 1995. Signposts to spirituality. Cape Town: Struik Christian Books. [ Links ]

James, M. 2008. The history and spirituality of the lay Dominicans in South Africa, 1926-1994. Unpublished thesis. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal. [ Links ]

Janzen, D. 2005. 'Mark 6: intentional formation in the way of Christ and the rule of the community along the lines of the old novitiate' in School(s) for conversion: 12 marks of a new monasticism. (Ed. Rutba House) Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books. [ Links ]

Jenkins, H.P. 2006. A study of the origins, development and contemporary manifestations of Christian retreats. Unpublished thesis. Pretoria: University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Kauffman, I. 2009. "Follow me": a history of Christian intentionality. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock. [ Links ]

Kretzschmar, L. 1998. Privatization of the Christian Faith: Mission, Social Ethics and the South African Baptists. Accra, Ghana: Legon Press & Asempa Publishers. [ Links ]

Kretzschmar, L. 2008. 'Christian spirituality in dialogue with secular and African spiritualities with reference to moral formation and agency' in Theologia Viatorum, Vol 32 No. 1, 63-96. [ Links ]

Latourette, K.S. 1953. A history of Christianity. New York: Harper & Brothers. [ Links ]

Loewen, H.J.L. 1988. 'Anabaptist theology' in New dictionary of theology. (Eds. Ferguson, S.B. and Wright, D.F.) Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press. [ Links ]

MacIntyre, A. 1981. After virtue: a study in moral theory. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [ Links ]

Merton, T. 2003. The inner experience. Ed. W.H. Shannon. San Francisco: Harper. [ Links ]

McKenna, M.M. 2005. 'Mark 1: relocation to abandoned places of empire' in School(s) for conversion: 12 marks of a new monasticism. (Ed. Rutba House) Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books. [ Links ]

Moll, R. 2005. 'The new monasticism' in Christianity Today, Vol. 49. No. 9 (September 2005). http://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2005/september/16.38.html Accessed October 2012. [ Links ]

Pew 2006. Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life: 10 Nation Survey of Renewalists. http://www.pewforum.org/uploadedfiles/Orphan_Migrated_Content /pentecostals-topline-06.pdf Accessed March 2013. [ Links ]

Rasmussen, L.L. 1990. Dietrich Bonhoeffer - his significance for North Americans. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress. [ Links ]

Richardson, N. 'Sanctorum Communio in a time of reconstruction? Theological pointers for the church in South Africa' in Journal of Theology for South Africa 127 (March 2007). [ Links ]

Rutba House, ed. 2005. School(s) for conversion: 12 marks of a new monasticism. Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books. [ Links ]

Schutte, C.H. 2006. The relevance of the Benedictine, Franciscan, and Taizé monastic traditions for retreat within the Dutch Reformed tradition: an epistemological reflection. Unpublished dissertation. University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Storey, P. 2012. "Banning the flag from our churches: learnings from the Church-State struggle in South Africa" in Bentley, W. and Forster, Dion A. (eds.) Between capital and Cathedral: Essays on Church-State relationships. Pretoria: Research Institute for Theology and Religion, University of South Africa, 1-20. [ Links ]

Visser, W. 2004. "Shifting RDP into GEAR." The ANC governments dilemma in providing an equitable system for social security for the "new" South Africa. http://sun025.sun.ac.za/portal/page/portal/Arts/ Departemente1/geskiedenis/docs/rdp_into_gear.pdf Accessed March 2013. [ Links ]

Wilson-Hartgrove, J. Report on new monasticism gathering: the unveiling of a contemporary school for conversion. Unpublished report in my possession, dated 25 June 2004. [ Links ]

1 This paper was originally presented at the SAMS 'Emerging Theologians' pre-conference in Pretoria, March 2011.

2 Carl Brook directs Crusade for Christ, a missions organisation in KwaZulu-Natal. He may be contacted at carlbrook@outlook.com

3 The term preferred in new monastic literature to the more conventional 'monks' and 'nuns.'

4 Intentional community' is not simply defined, though a few common features are apparent: it a) is residential, b) is planned, c) has some kind of common vision - whether religious, ecological, etc. One popular definition reads: An 'intentional community' is a group of people who have chosen to live together with a common purpose, working cooperatively to create a lifestyle that reflects their shared core values. The people may live together on a piece of rural land, in a suburban home, or in an urban neighborhood, and they may share a single residence or live in a cluster of dwellings. http://wiki.ic.org/wiki/Intentional_Communities accessed October 2012.

5 http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/1007307/New-Religious-Movement accessed October 2012.

6Finkenwalde was the location of the Preacher's Seminary and intentional community that Bonhoeffer directed from 1935 to 1937.