Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.44 n.1 Pretoria Feb. 2024

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v44n1a2331

ARTICLES

Capturing classroom practice using a mixed methods design

Kellie Steinke

School of Social Sciences, BA Faculty, University of Mpumalanga, Mbombela, South Africa kelle.steinke@ump.ac.za

ABSTRACT

In this article I focus on the use of mixed methods in designing a classroom observation instrument known as the Facilitative Orientation to Reading Teaching (FORT). The instrument was designed to capture the teaching of reading and formed part of a project that took place in 2 Kwa-Zulu Natal primary schools. Participants were 8 teachers and their learners. The goal was to investigate how a teacher's pedagogical content knowledge can affect the literacy acquisition of Foundation and Intermediate Phase learners. In the study reported on here I used a facilitative-restrictive teaching and learning model based on the theories of, among others, Bernstein and Vygotsky, as well as Scarborough's Reading Rope theory. The instrument design was based on an original classroom instrument that captured only quantitative data. Through the addition of qualitative data, the instrument could capture classroom practice more accurately. Findings indicate that, ultimately, 1 of the participating teachers appeared to be successfully leading their learners from decoding to comprehension across the important Grade 3 to 4 threshold, where learners are expected to move from learning to read to be being able to learn from reading.

Keywords: classroom research; education; literacy; mixed methods; reading; scaffolding

Introduction

In this article I discuss aspects of a larger study that took place in Kwa-Zulu Natal with eight participating teachers and their learners in Grade 3 and 4 classrooms. An instrument, known as the Facilitative Orientation to Reading Teaching (FORT) was designed to capture the teaching of reading. The overall focus was to capture how teachers' pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) can beneficially affect learners in their acquisition of literacy and whether additional training in the teaching of reading for teachers positively affects their teaching (Vaknin-Nusbaum, Nevo, Brande & Gambrell, 2020). I discuss how the use of mixed methods categories within the FORT provided an in-depth view of teaching and learning within the classroom.

Although the study was not initially designed with comparative data, the participating teachers were eventually divided into two groups of four each to facilitate comparison. The first four, known as Group A, used the standard government school syllabus, called the Curriculum Assessment Policy Statements or CAPS (Hoadley, 2005). Group B included four teachers who used their additional training alongside the CAPS. I employed a mixed methods research paradigm in order to capture in detail, not just what took place during the observed lessons, but also how and why, for example, what teachers were using, as well as the motivations, beliefs, attitudes and theories that underpinned their teaching (Alasuutari, Bickman & Brannen, 2008). The main research questions were as follows:

• What do teachers do in the teaching of reading that enables their learners to become effective readers?

• Do these teachers teach in practice as they say they say they do?

• Does the use of additional training in addition to CAPS help in teaching and learning?

In order to answer these questions, I assumed a foundation of best practice in the teaching of reading (Gambrell, Malloy & Mazzoni, 2011). A brief overview of the literature from before 1994 to the present is provided below, and illustrates the general lack of effective change of teaching practice within the education system over the last three decades.

A Review of the Literature

Low literacy levels remain a serious challenge in South Africa and have seen little change since before 1994 under the apartheid system. Instead, the emphasis on rote learning continues, with a lack of concern for comprehension and inadequate pre-service teacher training. In addition, English is the language of learning and teaching (LoLT) in most schools from the intermediate grades onwards (Chick, 1996; Klapwijk, 2015; Pretorius, 2002). The current South African Language and Education policy requires an additive approach to multilingualism in which learners should receive their initial schooling in their mother tongue. However, the reality is that for the majority of learners in South Africa, English is a foreign language, with little chance to practice the language during class time and inadequate teacher competency in the language itself (Fesi & Mncube, 2021). The latest results of the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS), the global benchmark for ability in reading and numeracy, shows clearly that in 2021, South Africa performed poorly (National Professional Teachers' Organisation of South Africa [Naptosa], 2023; Van Staden & Zimmerman, 2017). The research studies discussed below provide an overview of the situation regarding the teaching of reading in Grades 3 and 4 classrooms across the last 30 years, and highlight the importance of the original study from which this article originated.

As far back as 1992, Wildsmith used a classroom observation instrument known as the Communicative Orientation to Language Teaching, or COLT, to examine both attitudes and perceptions of teachers, as well as to investigate whether these teachers could act as facilitators of change. This pre-democracy study highlights the tendency towards rote learning, along with whole-class responses and tight teacher control over both dialogue and participation in the classroom (Wildsmith-Cromarty & Balfour, 2019).

Moving forward several years, Ursula Hoadley (2005) used case studies with Grade 3 learners in a South African township to observe the teaching of reading within the classroom, and captured lessons in numeracy, English and isiXhosa. She also developed a quantitative classroom-based observation instrument founded upon Bernstein's idea of code theory and the pedagogic device (Bernstein, 1999), and found that although teachers had relaxed some control over certain educational boundaries, they were still maintaining tight control over classroom dialogue and participation.

Nkosi (2011) undertook a study across Grades 2 and 3 to discover how teachers taught reading. She found that teachers were inadequately trained to teach and tended to rely on decoding at the expense of comprehension. They were strongly influenced by their beliefs and tended to concentrate on teaching in English at the expense of indigenous languages.

Lebese and Mtapuri (2014) investigated the acquisition of reading in both Sepedi and English, with Grade 3 learners at a rural school. They found that the teachers used Sepedi to teach English, and that the Sepedi learners were not developing reading skills in either English or their mother tongue.

Makiwane-Mazinyo and Pillay (2017) studied Grade 4 learners using a descriptive survey to uncover difficulties that teachers faced in teaching English reading to their learners in rural KwaZulu-Natal. They discovered that these learners were unable to read and that there were serious challenges regarding the use of English as LoLT. Teachers were struggling to teach reading and it appeared to stem from inadequate pre-service teacher training.

Also in 2017, Ursula Hoadley observed teaching practice by teachers at 14 schools who were using CAPS with Grade 3 learners, and how the teaching style, or pedagogy, could influence learner outcomes. Hoadley found that teachers tended to stick to the policy guidelines quite strictly but seemed to lack knowledge of how to assist the learners in comprehension, or how to comprehend concepts (Hoadley, 2017).

Mgijima and Makalela (2016) carried out classroom observations of the use of trans-languaging in the teaching of reading. Trans-languaging refers to two or more languages being particularly alternated in interaction between the teacher and the learners to help the learners to grasp concepts and understand information. The findings show that this had a positive effect in terms of the learners' understanding and highlighted the importance of indigenous languages for the purposes of learning and teaching.

In conclusion to this review, Stoffelsma and Van Charldorp (2020) observed how teachers and learners in township schools engaged with texts, as well as the prevalence of "chanted" whole-class responses during classroom interactions. The researchers stated that it was not clear whether teaching and learning was actually taking place in these classrooms.

The common thread that runs through all the findings discussed above is that learners are not able to read for meaning, and little has changed in classroom practice when it comes to the teaching of reading. On the whole, the teaching of reading has remained static and traditional, with teachers firmly in control and limited learner agency, which is clearly not beneficial (Melgoza Mendoza & Rojas Vite, 2019). Although the above studies were conducted with Grades 3 and 4 learners, my study was unique in that I investigated the decoding to comprehension process that needs to take place across the Grade 3 and 4 threshold, and which necessitated the development of the FORT.

Theoretical Discussion

In order to create an observational classroom instrument that could accurately capture the effective teaching of reading, the categories in such an instrument needed to be based on solid theories of both reading and best teaching practice. Whereas the original COLT had been based on theories of communicative natural language processes, the FORT model had to be based upon more eclectic, yet principled, practices (Wildsmith, 1992) as natural approaches alone had been shown to be ineffective in preparing learners for academic success (De Clercq, 2014).

The model that was developed has a facilitative-restrictive theoretical base (see Steinke & Wildsmith-Cromarty, 2019) and is founded on classical theories of practices such as explicit teaching and assessment (Bernstein, 1990), the role of the teacher as knowledgeable "other" (Vygotsky, 1978), the importance of dialogue (Tough, 1977), scaffolded teaching, and the use of both top-down and bottom-up processes in the teaching of reading. The latter is encapsulated in Scarborough's Reading Rope theory in which comprehension is defined as an integrated set of skills that come together to create a skilled reader (Scarborough, 2001).

The FORT categories had to allow the capture of classroom dialogue, practices and activities that could capture the teaching of reading and had to include categories that accounted for, among others, possible discourse events between teacher and learner. It had to include various reading strategies, classroom participation, and management issues such as discipline and classroom organisation. Again, these had to be based on teaching practices that were acknowledged to be effective (Rose, 2006, 2011).

In addition, the theory had to provide a suitable explanation for the term "pedagogical content knowledge" or PCK. According to Shulman (1987), PCK describes the in-depth knowledge that teachers have of the subject content matter as well as pedagogical content. Teachers need to be able to transform their knowledge into learning for their learners (Shulman, 1987). Although PCK is a somewhat difficult concept, as it really remains within the mind of individual teachers, it can become explicit through their teaching and can, therefore, be captured through observation.

Finally, the teaching group in this study that used additional training used two particular types of reading teaching approaches (alongside CAPS) which were READ and the Learning to Read: Reading to Learn approach, or R2L. READ is outcomes-based and involves the use of extensive reading strategies (Schollar, 2001). R2L, on the other hand, uses the aforementioned best practices, such as explicit teaching and assessment criteria (Bruner, 1971; Rose, 2018) and a form of scaffolded interaction, rather than the usual initiation-feedback-response cycle (Rose, 2004).

Methodology

The focus of this article is the development of the FORT and how the amalgamation of quantitative and qualitative data within the same category could create a unique and in-depth picture of classroom practice. While most of the categories in the instrument were quantitative, it became clear during its development that certain categories needed to be able to capture qualitative data as well. The data presented highlight these particular mixed methods categories. The full list of the research instruments is listed below, and when analysed and compared, they allowed for triangulation.

• The classroom observation instrument;

• Pre- and post-reading assessments;

• Thirty-five hours of recorded video sessions of classroom lessons that allowed for observation and analysis of teaching practice; and

• Interviews with eight teachers to understand and record their attitudes and beliefs that underpinned their teaching practice.

With the research instruments selected, the study was realised as a convergent, parallel design, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 provides an illustration of how the mixed methods research design allowed for separate data streams to be collected and analysed, parallel to each other. These various streams were then brought together in a convergent design (Creswell, 2003). The question that I kept in mind during the design was, When using a mixed methods approach, what information would be new? In other words, what data would not have been captured had only quantitative or qualitative data been collected. Eventually, this project was realised as an explanatory, multiple case study, with each participating teacher and her classroom regarded as one case (Feagin, Orum & Sjoberg, 2020). The setting for a case study can be a physical area, such as a classroom, and contain a social component, such as the interaction between learners and teachers. Collecting the data of individual cases and placing them alongside each other leads to a series of data collection episodes that allow for the triangulation of data and increased validity (Burton & Bartlett, 2009).

The Development of the FORT

The COLT (cf. Appendix B) captures communicative language teaching (Fröhlich, Spada & Allen, 1985) in second language classrooms, and contains a reading component (Mady, 2020). The COLT is divided into two main sections as is the FORT. An illustration of the FORT instrument is provided in some detail in a previous paper (cf. Steinke & Wildsmith-Cromarty, 2019).

Part A of the FORT is concerned with the teaching of reading and class participation, modalities (including integrated teaching, spelling, punctuation and reading strategies), and classroom and lesson arrangements. Part B contains categories that capture the interaction within the classroom via varied types of speech acts and discourse events (Tough, 2012). The FORT quantitative data consists of events and occurrences captured across 5-minute time periods, with 20 minutes counting as one lesson. Ticks used to mark frequency were totalled, and plotted on graphs. However, the quality and content of events also needed to be accounted for (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2007).

This meant that qualitative categories create a link between Sections A and B of the FORT. Examples of these are provided below and explained in more detail.

• The materials and activities;

• The pacing and sequencing of the lesson;

• A scaffolded teaching and learning approach, which forms a thread throughout the entire instrument and is reflected, for example, in not just the activities but also within concepts such as classroom control and learner agency, the various types of interaction between participants, integrated lessons, and inferential and extended open questions; and

• An "Other" category in Part B under the interaction between teacher and learner and vice versa. Such a category could allow for both non-verbal and body language communication and could provide clues about how engaged the learners were in the recorded lessons (Zeki, 2009); and

• Categories that allow for the capture of an elaborated interaction cycle, which can extend learning. A more detailed illustration follows.

Materials and Activities

I start the illustration with an explanation of the "materials and activities" category from Part A of the FORT. An example of the type of materials used in a scaffolded, Grade 3 lesson might be sentence strips, blackboards (for writing and erasing), along with chalk and pencils. Learners work as a class, initially reading a big book along with the teacher. They then find, for example, words, or punctuation, in a sentence strip, then cut out what they have found. When this is complete, they jumble the separate pieces together and then reassemble them into the correct original sentence. In the FORT, the materials are paper, scissors and such like, while the activity itself forms part of a scaffolded lesson where learners are reading, and learning to recognise words and punctuation marks, and how these function within sentences (Rose, 2011). The learners could be observed via the recorded video material to determine their level of engagement during the activity.

When capturing data for these activities on the FORT, this evidence is initially placed within the materials and activities category, and could be recorded as, for example, scissors and paper sentence strips. However, the data that indicates body language or engagement levels would also need to be placed in the aforementioned "Other" category in Part B. One, therefore, obtains two important data streams emerging from one event or activity. In addition, the resulting data needed to be triangulated with the observations and the interviews.

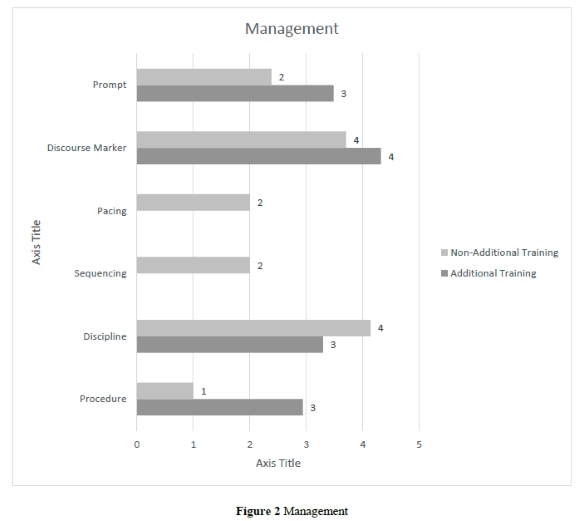

Further triangulation occurs as one examines the categories that fall under "management" in Part A. Here the focus is on three main categories, namely, procedure, pacing, and sequencing. As graphic presentation of the data, a diagram for management is provided in Figure 2. The top, lighter grey bars represent data from Group A (teachers who only used the CAPS), while the bottom, darker bars represent Group B (teachers who used additional training along with the CAPS).

The data for "procedure" from Figure 2 provide an illustration of why it was important to integrate the findings for that category with those of material and activities. Group B appeared to score higher than Group A on this graph. This could well indicate that more activities were taking place, as much of what was recorded in procedure consisted of, for example, handing out the tools, paper strips, and pencils, and scissors for the R2L reading activities in which the learners were engaged (Pinter, 2017).

Other sub-categories in management that required triangulation with the semi-structured interviews were pacing and sequencing. Pacing involves the rate of content coverage, or how class time is allocated. Sequencing is the order in which content or concepts are taught, and build upon one another (Rose, 2004).

In its quantitative mode, the FORT only captures two examples each where the pacing and sequencing were overtly captured as they were deliberately relaxed by one of the teachers in Group A. On these occasions, the teacher returned to an earlier lesson after having realised that the learners had not grasped the content well. Overtly, the relaxing of the pacing and sequencing boundaries did not occur in Group B. However, if one examines the qualitative data, the boundaries for both the pacing of the curriculum and the sequencing of the content were inherently relaxed by Group B due to the scaffolded teaching approach that they used (Collet-Sabé & Martori, 2018). A further example of data triangulation is how the FORT captures meaningful interaction.

Part B of the FORT contains data obtained from interactions between teacher and learner and vice-versa. It consists of various speech events that may occur, including the choice of language and code switching. In its quantitative mode, the data reflect what has been said in terms of its purpose, e.g., an explanation or a request for information, and its frequency. However, it is not simply the amount of teacher-talk alone that engages learners and brings about learning, but what and how it is said (Gámez & Lesaux, 2015).

Traditionally, interactions in the classroom have followed an initiation-response-feedback pattern (Tomasello & Farrar, 1986). In scaffolded teaching, both teachers and learners need to be engaging in meaningful interaction, using open-ended questions that challenge and engage the learner (Rose & Martin, 2012). This is in contrast to traditional classroom interaction where the learners may chant answers together as a group, but no learning is taking place (Pretorius & Klapwijk, 2016). On the other hand, meaningful, quality interaction between teacher and learner can facilitate not only learning but also social development for learners (Silinskas, Pakarinen, Lerkkanen, Poikkeus & Nurmi, 2017).

Findings

Beginning with management, the teachers in Group B tended to focus more on procedure, which may be an indication of increased activities taking place. One can obtain this data as one links the materials and activities category to procedure (a category that is contained within the larger management graph), as it gives a clearer picture of what was happening in the classroom. As mentioned previously, data were obtained over a series of lessons, captured via 5-minute increments on the FORT instrument, analysed, and presented in graphic form. While Figure 2 was included in this article in order to provide an illustration of the data presentation, further sections of the FORT instrument itself - PCK and the Teaching of Reading and Management - are presented in Appendices A and B. In this way, classroom teaching practice is illustrated despite space limitations. A more detailed diagram of the FORT instrument is provided in Steinke (2018).

The scaffolded form of interaction and teaching of reading (R2L) used by Group B teachers has as one of its main theoretical foundations the inherent relaxing of the traditional boundaries around both pacing and sequencing to cater for weaker learners who may have fallen behind. However, only Group A teachers provided any indication of overt softening of these boundaries captured on the FORT. Thus, without an understanding of the underlying theory of the teaching, or the materials and activities taking place, one may have no concept that the relaxing of the boundaries was taking place. The CAPS curriculum by itself tends to be somewhat rigid and prescriptive in this area (Naidoo, 2011).

To reiterate, the category "Other" refers to non-verbal and body language cues from learners, which could take the form of, for example, facial expressions and/or physical movement (Martin & Rose, 2007). Group B teachers who used their additional training tended to score higher on the other category, as their learners were providing a greater and more varied amount of emotional responses, such as laughter. This is possibly an indication of a greater amount of learning engagement (Lovorn, 2008).

Additionally, the term "meaningful interaction" refers to interactions where the teacher initiates dialogue with the intention of bringing about elaborated responses that may facilitate learning, rather than relying on whole-class chanted responses. This facilitative interactive cycle is founded upon the idea that children learn ways of interacting within the home environment, and that this later forms a basis for the orientation towards academic learning (Tomasello & Farrar, 1986). The teacher facilitates comprehension and helps the learner to uncover inferences within the text. As teachers do this, the traditional boundaries that exist between everyday and academic language are relaxed. This boundary can then be rebuilt and strengthened via the extended dialogue that the teacher provides for the learner (Bernstein, 1990). Findings show that the teachers in Group B, who had additional training in the teaching of reading, initiated more meaningful dialogue and used more extended open questions, focusing on inferential comprehension as well as referential comprehension. They used a variety of comprehension strategies. In addition, they provided an extensive and varied amount of teacher-talk to their learners and appeared overall to have a more effective teaching style that had the learners engaged in their respective lessons. However, despite this, the learner responses to teachers, for both groups, remained limited.

Discussion

It became clear from the data that both groups of teachers retained tight control of their classroom interactions and that learner agency was restricted (Hoadley, 2017). Rote learning, although it has its role in teaching and learning, is known to hinder these processes when relied upon in educational contexts (Wilson, 2016). Despite the fact that teachers had said in the interviews that they believed that they were allowing for two-way dialogue in the classroom between learner and teacher, the data indicate that these teachers all tended towards a teacher-fronting style (Mudzielwana, 2012).

Furthermore, the pre- and post-reading assessments indicate that during the course of the year, learners taught by teachers in Groups A and B showed similar and generally unremarkable reading level gains. It appeared that neither of the teacher groups were successfully leading their learners from decoding to comprehension. The value of this research is that it is not only the first South African study to examine the transition from decoding to comprehension across Grades 3 and 4 but also that it has provided a solid, effective classroom observation instrument that can capture teaching practice. Traditional ways of teaching tend to be firmly entrenched, and it is recommended that these teachers, while they do benefit from additional training, might be assisted even further through coaching (Taylor, Cilliers, Prinsloo, Fleisch & Reddy, 2017), which involves expert mentors who work with the teachers to create a relationship that is tailored specifically to their needs, and thereby assist them to teach more effectively (Taylor et al., 2017).

Conclusion

In this article I discuss how the development of a mixed methods classroom observation instrument, called the FORT, enabled the investigation of how PCK affects teacher efficacy in the teaching of reading. Initially separate quantitative data were recorded from the pre- and post-research reading tests, as well as from the FORT, while qualitative data were collected in a parallel fashion from classroom observations, video recordings, teacher interviews, and the qualitative FORT categories. The fact that the FORT was a mixed methods observation instrument allowed the quantitative data to be placed alongside qualitative categories. This meant that the separate data streams could converge and allow researchers a holistic view of not just what happened in the classroom, or how often, but also why. Ultimately, using a mixed methods design with default categories allowed the FORT to be developed into a nuanced, sensitive instrument that could accurately capture the teaching of reading and related classroom practice.

Acknowledgement

I wish to thank the EDTP-SETA for their generous funding of this project.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Alasuutari P, Bickman L & Brannen J (eds.) 2008. The Sage handbook of social research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Bernstein B 1990. Class, codes and control (Vol. IV). London, England: Routledge. [ Links ]

Bernstein B 1999. Official knowledge and pedagogic identities. In F Christie (ed). Pedagogy and the shaping of consciousness: Linguistic and social processes. London, England: Continuum. [ Links ]

Bruner JS 1971. The relevance of education. New York, NY: W.W. Norton. [ Links ]

Burton D & Bartlett S 2009. Key issues for education researchers. London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Chick JK 1996. Safe-talk: Collusion in apartheid education. In H Coleman (ed). Society and the language classroom. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Collet-Sabé J & Martori JC 2018. Bridging boundaries with Bernstein: Approach, procedure and results of a school support project in Catalonia. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 39(8):1126-1142. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2018.1478718 [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2003. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (2nd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

De Clercq F 2014. Improving teachers' practice in poorly performing primary schools: The trial of the GPLMS intervention in Gauteng. Education as Change, 18(2):303-318. https://doi.org/10.1080/16823206.2014.919234 [ Links ]

Feagin JR, Orum AM & Sjoberg G (eds.) 2020. A case for the case study. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press. [ Links ]

Fesi L & Mncube V 2021. Challenges of English as a first additional language: Fourth grade reading teachers' perspectives. South African Journal of Education, 41(3):Art. #1849, 11 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v41n3a1849 [ Links ]

Fröhlich M, Spada N & Allen P 1985. Differences in the communicative orientation of L2 classrooms. Tesol Quarterly, 19(1):27-57. https://doi.org/10.2307/3586771 [ Links ]

Gambrell LB, Malloy JA & Mazzoni SA 2011. Evidence-based best practices in comprehensive literacy instruction. In L Mandel Morrow & LB Gambrell (eds). Best practices in literacy instruction (4th ed). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Gámez PB & Lesaux NK 2015. Early-adolescents' reading comprehension and the stability of the middle school classroom-language environment. Developmental Psychology, 51(4):447-458. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038868 [ Links ]

Hoadley U 2017. Learning to fly: Pedagogy in the Foundation Phase in the context of the CAPS reform. Journal of Education, 67:13-38. https://doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i67a01 [ Links ]

Hoadley UK 2005. Social class, pedagogy and the specialization of voice in four South African primary schools. PhD dissertation. Cape Town, South Africa: University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Klapwijk NM 2015. EMC2 = comprehension: A reading strategy instruction framework for all teachers. South African Journal of Education, 35(1):Art. # 994, 10 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/201503062348 [ Links ]

Lebese MP & Mtapuri O 2014. Biliteracy development: Problems and prospects - an ethnographic case study in South Africa. Bangladesh e-Journal of Sociology, 11(1):74-88. [ Links ]

Leech N & Onwuegbuzie A 2007. An array of qualitative data analysis tools: A call for data analysis triangulation. School Psychology Quarterly, 22(4):557-584. https://doi.org/10.1037/1045-3830.22.4.557 [ Links ]

Lovorn M 2008. Humor in the home and in the classroom: The benefits of laughing while we learn. Journal of Education and Human Development, 2(1):1 -12. [ Links ]

Mady C 2020. Teacher adaptations to support students with special education needs in French immersion. In L Cammarata & TJ Ó Ceallaigh (eds). Teacher development for immersion and content-based instruction. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamin' s Publishing. [ Links ]

Makiwane-Mazinyo M & Pillay P 2017. Challenges teachers encounter in teaching English reading to the intermediate phase learners in the uThungulu district schools in KwaZulu Natal. Gender and Behaviour, 15(4):10453-10475. [ Links ]

Martin JR & Rose D 2007. Interacting with text: The role of dialogue in learning to read and write. Foreign Languages in China, 4(5):66-80. [ Links ]

Melgoza Mendoza DM & Rojas Vite C 2019. The teacher's role in the classroom and new trends. Ciencias Huasteca Boletín Científico de la Escuela Superior de Huejutla. 13:17-21. Available at https://repository.uaeh.edu.mx/revistas/index.php/huejutla/article/view/3534/4971. Accessed 29 February 2024. [ Links ]

Mgijima VD & Makalela L 2016. The effects of translanguaging on the bi-literate inferencing strategies of fourth grade learners. Perspectives in Education, 34(3):86-93. https://doi.org/10.18820/2519593X/pie.v34i37 [ Links ]

Mudzielwana NP 2012. Teaching reading comprehension to grade 3 Tshivenda-speaking learners. PhD thesis. Pretoria, South Africa: University of Pretoria. Available at https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/28049/Complete.pdf?sequence=10&isAllowed=y. Accessed 29 February 2024. [ Links ]

Naidoo M 2011. Why OBE failed. Available at http://www.muthalnaidoo.co.za/education-othermenu-122/269-why-obe-failed. Accessed 7 October 2023. [ Links ]

National Professional Teachers' Organisation of South Africa 2023. Reading with comprehension crisis in South Africa - PIRLS report. National News Flash, 19. Available at https://naptosa.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/NAPTOSA-National-News-Flash-19-of-2023-PIRLS-Report.pdf. Accessed 11 July 2023. [ Links ]

Nkosi ZP 2011. An exploration into the pedagogy of teaching reading in selected foundation phase isiZulu home language classes in Umlazi schools. PhD thesis. Durban, South Africa: University of KwaZulu-Natal. Available at https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=aea6d0fe3ef2434c81b8cc4d8095be98a486ece3. Accessed 29 February 2024. [ Links ]

Pinter A 2017. Teaching young language learners (2nd ed). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Pretorius EJ 2002. Reading and applied linguistics - a deafening silence? Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 20(1-2):93-103. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073610209486300 [ Links ]

Pretorius EJ & Klapwijk NM 2016. Reading comprehension in South African schools: Are teachers getting it, and getting it right? Per Linguam: A Journal for Language Learning, 32(1):1-20. https://doi.org/10.5785/32-1-627 [ Links ]

Rose D 2004. Sequencing and pacing of the hidden curriculum: How indigenous children are left out of the chain. In J Muller, B Davies & A Morais (eds). Reading Bernstein, researching Bernstein. London, England: RoutledgeFalmer. [ Links ]

Rose D 2006. A reading based model of schooling. Pesquisas em Discurso Pedagógico, 4(2):1 -22. https://doi.org/10.17771/PUCRio.PDPe.9740 [ Links ]

Rose D 2011. Meaning beyond the margins: Learning to interact with books. In S Dreyfus, S Hood & M Stenglin (eds). Semiotic margins: Meaning in multimodalites. London, England: Continuum International Publishing Group. [ Links ]

Rose D 2018. Languages of schooling: Embedding literacy learning with genre-based pedagogy. European Journal of Applied Linguistics, 6(1):59-89. https://doi.org/10.1515/eujal-2017-0008 [ Links ]

Rose D & Martin JR 2012. Learning to write, reading to learn: Genre, knowledge and pedagogy in the Sydney school. London, England: Equinox. [ Links ]

Scarborough H 2001. Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory and practice. In S Neuman & D Dickinson (eds). Handbook for research in early literacy. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Schollar E 2001. A review of two evaluations of the application of the READ primary schools program in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. International Journal of Educational Research, 35(2):205-216. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-0355(01)00017-9 [ Links ]

Shulman L 1987. Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1):1-23. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.57.1.j463w79r56455411 [ Links ]

Silinskas G, Pakarinen E, Lerkkanen MK, Poikkeus AM & Nurmi JE 2017. Classroom interaction and literacy activities in kindergarten: Longitudinal links to Grade 1 readers at risk and not at risk of reading difficulties. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 51:321-335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.09.002 [ Links ]

Steinke K & Wildsmith-Cromarty R 2019. Securing the FORT: Capturing reading pedagogy in the Foundation Phase. Per Linguam: A Journal for Language Learning, 35(3):29-58. https://doi.org/10.5785/35-3-806 [ Links ]

Steinke KJ 2018. The pedagogical content knowledge of teachers and its effect on enliterating Grade three and four learners. PhD thesis. Potchefstroom, South Africa: North-West University. Available at https://repository.nwu.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10394/35997/Steinke_KJ.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 29 February 2024. [ Links ]

Stoffelsma L & Van Charldorp TC 2020. A closer look at the interactional construction of choral responses in South African township schools. Linguistics and Education, 58:100829. https://doi.org/10.1016/jlinged.2020.100829 [ Links ]

Taylor S, Cilliers J, Prinsloo C, Fleisch B & Reddy V 2017. The early grade reading study: Impact evaluation after two years of interventions (Technical Report). Pretoria, South Africa: Department of Basic Education. Available at https://www.jet.org.za/clearinghouse/projects/primted/resources/language-and-literacy-resources-repository/egrs-technical-report-13-oct-2017.pdf. Accessed 4 April 2019. [ Links ]

Tomasello M & Farrar MJ 1986. Joint attention and early language. Child Development, 57(6):1454-1463. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130423 [ Links ]

Tough J 1977. Talking and learning. London, England: Ward Lock Educational. [ Links ]

Tough J 2012. The development of meaning: A study of children's use of language. London, England: Routledge. [ Links ]

Vaknin-Nusbaum V, Nevo E, Brande S & Gambrell L 2020. Reading and writing motivation of third to sixth graders. Reading Psychology, 41(1):44-70. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2019.1674435 [ Links ]

Van Staden S & Zimmerman L 2017. Evidence from the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) and how teachers and their practice can benefit. In V Sherman, RJ Bosker & SJ Howie (eds). Monitoring the quality of education in schools: Examples of feedback into systems from developed and emerging economies. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense. [ Links ]

Vygotsky LS 1978. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Wildsmith R 1992. Teacher attitudes and practices: A correlational study. PhD thesis. London, England: University of London. [ Links ]

Wildsmith-Cromarty R & Balfour RJ 2019. Language learning and teaching in South African primary schools. Language Teaching, 52(3):296-317. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444819000181 [ Links ]

Wilson M 2016. Instructors' views on Japanese use in the EDC classroom. New directions in Teaching and Learning English Discussion, 4:275-283. Available at https://rikkyo.repo.nii.ac.jp/?action=repository_uri&item_id=16104&file_id=18&file_no=1. Accessed 17 October 2022. [ Links ]

Zeki CP 2009. The importance of non-verbal communication in classroom management. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 1(1):1443-1449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2009.01.254 [ Links ]

Received: 21 July 2022

Revised: 24 October 2023

Accepted: 6 December 2023

Published: 29 February 2024

Appendix A: Section A of the FORT - PCK and the Teaching of Reading

Appendix B: Section A of the FORT Part 2 - Management