Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.44 n.1 Pretoria Feb. 2024

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v44n1a2405

ARTICLES

The effect of life-design-based counselling on high school learners from resource-constrained communities

Che Jude; Jacobus Gideon Maree

Department of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Education, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa che.jude@yahoo.com

ABSTRACT

In the study reported on here we explored the influence of life-design counselling intervention on high school learners with career indecision who hail from resource-poor contexts in rural South Africa. Purposeful sampling was used to select 17 participants from a resource-constrained area. A mixed-methods group-based intervention embedded in social constructionism was used to address the research questions. The qualitative outcomes for the 17 participants who constituted the intervention group are reported in this article. Data were generated using life-design-based intervention strategies and qualitative (postmodern) techniques. The intervention enhanced the facets of career adaptability of participants and improved their ability to make career decisions. The results show that participants benefited in planning their future and preparing to leave school. The value of the intervention described in this article can be confirmed in longitudinal research with larger samples of diverse participants and contexts as well as different design and assessment measures.

Keywords: career adaptability; career indecision; life-design-based counselling; resource-constrained community

Introduction

Despite having to deal with insufficient clarity about what the concept of work currently entails, career counsellors around the world (also in South Africa) are trying to address the challenges that career counselling clients face. An unpredictability regarding the future of work is becoming increasingly arduous because traditional jobs are rapidly fading away and employers' and employees' views about the meaning of work and careers are changing (Maree, JG 2017). The field of career counselling faces various emerging career issues that contradict traditional career conceptions. The complex nature of the work world is, for instance, currently characterised by scarce job opportunities, poor working conditions, a lack of decent work for many, challenges in making career decisions, and matters relating to social justice. These issues are all linked to the bigger issue of facilitating employability (in other words, facilitating the capacity to enter the job market and switching from one job to another within the context of fluctuating macroeconomic variables) (Maree, JG 2016a, 2016b; Watson, 2013).

Since it is a nation that embodies a multicultural and diverse socioeconomic population, South Africa (SA) stands out among countries where variances in career decision-making processes are most apparent. The significant disparity in socioeconomic status and income levels among South Africa's population groups poses a challenge to career practitioners, researchers, educators, and theorists. Blustein, Franklin, Makiwane and Gutowski (2017) affirm that the South African economic context has given rise to significant questions about the utility of conventional wisdom in career psychology and unemployment studies, much of which is rooted in Western knowledge bases. Concern has been expressed by many researchers, including Akhurst and Mkhize (2006), Bischof and Alexander (2008), JG Maree (2016a), Stead and Watson (1998), and Watson (2013) regarding the indiscriminate application of career counselling theory and practice where such practice is inappropriate. Therefore, researchers in SA must reflect on developments and consider the appropriateness of these Western perspectives for the construction of career development in the local context (Blustein, McWhirter & Perry, 2005; Stead & Watson, 2017). Predominant career counselling approaches developed, adopted, and adapted for use in SA do not adequately address the career-counselling needs of the country's diverse population. A great need exists to develop career-counselling approaches that would address the needs of marginalisedi people.

Career Development/Counselling Challenges in Marginalised Contexts

When he visited SA in 1988, Super stated that "[c]areer development, for example, in some of the African and South Asian countries is a matter of fitting into what the family needs" (Freeman, 1993:263). Career development researchers and theorists are better placed to take the lead in bringing about new ways in which career development in SA can be made more relevant to the context. The contribution of scholars in the domain of career development will go a long way in addressing macrosystemic influences on individual career development. Career counsellors need to modify the practice of their profession in ways that will assist young people who live in marginalised communities. This support from career counsellors will assist young people in designing lives that will enhance their adaptability, lead to positive outcomes, facilitate participation in economic activities, and boost their self-esteem (Theron, 2017). Rankin and Roberts (2011) argue that in SA, as in most Western and industrialised societies, early exposure of young people to unemployment instils feelings of hopelessness about their future career trajectories. Such sentiments are not helpful to these young people, considering that psychological and social resources are needed to make major work-life transitions.

For several reasons, the psychosocial resources required to negotiate major transitions are not fostered in young people - especially in marginalised contexts. It is crucial to find ways to address these challenges because career counsellors - like other psychologists and helping professionals - are better placed to tackle the career adaptability of young people and challenge realities that perpetuate risk (Acevedo & Hernandez-Wolfe, 2014; Hart, Gagnon, Eryigit-Madzwamuse, Cameron, Aranda, Rathbone & Heaver, 2016). Advocating career adaptability in marginalised contexts and circumstances where negative outcomes in young peoples' development are predictable (Masten, 2014) includes providing the support necessary for people to be able to negotiate different career and life transitions. In this regard, people will have the capacity to withstand and accommodate career barriers and/or career turbulence that threaten to derail their career journeys (Arora & Rangnekar, 2016).

Del Corso and Rehfuss (2011:336-337) note that "the capacity for flexibility does not reside completely in individuals, rather [it is] formulated and developed through relationships with others. The attitudes or beliefs of family members, co-workers, supervisors, clients, organisations, government, and the media all impact on and influence individuals' attitudes and beliefs concerning career-related decisions." Marginalised communities should be assisted to reconsider the way young people are influenced. They should support young people in planning their futures and negotiating transitions in their lives. Providing psychosocial and psycho-educational support to expand adults' understanding of current occupations is one way of supporting the community. Introducing role models who embarked on diverse career journeys despite structural challenges is another way of supporting communities to reconsider how they influence young people. Against this background, the following paragraph states the purpose of our research followed by the research questions and methodology.

Marginalised individuals, especially young people, could be assisted to reflect on their career stories and decisions. According to David Tiedeman (Savickas, ML 2008), young people should give meaning to their vocational behaviour to understand where they are going. Imposing meaning on career behaviour requires young people to know their own story, which provides them with a sense of identity. Besides identity, career adaptability resources (concern, control, curiosity, and confidence) enable individuals to change chapters and how to go about the change. Career interventions can serve an important role in redirecting learners in rural and resource-constrained communities. Life-design counselling can be used as a model approach to assist high school learners in telling their own stories, guide families to support learners, and guide learners to make appropriate choices. In the next section we discuss the theoretical framework, "life design", that guided the study.

Theoretical Framework

Life design

There have been three major paradigms or traditions for career intervention. The first paradigm was used by counsellors to guide clients about their careers, the second was more about educating clients, and life design signifies the third paradigm (Savickas, ML 2015a). According to ML Savickas (2015b), life-design counselling is an intervention guided by certain principles that counsellors may use when assisting their clients in negotiating career transitions. In helping clients design their lives, career counsellors become more deliberate in their actions to bring about change in their clients. Counsellors also deliberately assist clients in understanding the reason for doing what they (clients) do (Savickas, ML 2015a). When researchers conduct treatment studies, life-design intervention principles help to enhance coherence within the life-design discourse.

The career construction theory of vocational behaviour in applied psychology (Savickas, ML 2013) and the Self-Construction Theory (Guichard, 2005) (the two cornerstones of life-design counselling) are distinguished from life designing as a discourse in the counselling profession (Savickas, ML 2011).

Career-construction counselling Initiated by Savickas, career-construction theory (CCT) enhances the interpretive model (Savickas, ML 2019). CCT focuses on how people design their careers using the narrative or the storied self. Whereas Duarte (2009) believes that personal and career interventions for the current century should assist clients in responding to concerns regarding the direction their lives should take, Rottinghaus, Falk and Eshelman (2017:92) postulate that "interpretive and interpersonal processes explain how individuals construct themselves, find vocational direction, and make meaning of their careers." Career interventions should seek to fit clients to work environments or careers and understand the interplay between clients and work environments/careers (Savickas, ML 2005). The process of constructing a career, ML Savickas (2019) argues, is psychosocial and calls for a certain degree of harmony between the individual and the society in which they live. Departing from Super's (1990) theory of career development, Savickas formulated career construction from whence a new paradigm for careers (life design) developed (Savickas, ML, Nota, Rossier, Dauwalder, Duarte, Guichard, Soresi, Van Esbroeck & Van Vianen, 2009). The following three career-counselling traditions are incorporated into CCT.

• Differential approach (focus is on individual differences - mostly on traits)

• Developmental approach (focus is on teaching people to advance following a predictable sequence over time, which culminates in a mature end state)

• The psychodynamic/storied approach (focuses on autobiographical narratives and professional identity)

The three paradigms listed above constitute the main domains of CCT, namely self-construction, career adaptability, and life themes (Savickas, ML 2019). Cochran (2011) and Rottinghaus et al. (2017) further argue that career counsellors should combine these domains in a story or narrative, which is constructed and deconstructed during the career counselling process.

Self-construction

In ML Savickas' (2019) view of CCT, "individuals construct their careers by imposing meaning on their vocational behaviour and occupational experiences" (p. 43). Moreover, occupations provide a mechanism to enhance social integration and contributing to societies. ML Savickas et al. (2009) claim that individuals' knowledge about themselves (identity) is shaped through interaction with the social environment. This shaping begins from infancy when the individual takes on the role of "actor" within the family context.

According to the self-construction theory, individuals actively construct themselves through narration or storytelling in social interaction. Rottinghaus et al. (2017) maintain that the interaction (social) through discourse enables individuals to construct themselves by assimilating cultural norms and values that create an identity in the context of the family of origin. The authors say that this identity is further enhanced as the individuals interact in social settings outside the family. Guichard's (2005) suggestion that individuals' identities are continually unfolding and that the active construction of the self by conversing during social communication plays a role in shaping people's identities, is fundamental to self-construction.

Self- and career-construction counselling (applied to the life-design-counselling discourse) promotes career adaptability, which enhances career decidedness (Nota, Santilli & Soresi, 2016). In this article self- and CCT are applied to the life-design-counselling discourse.

Examples of research on life-design-based counselling in Global South contexts

The works of researchers such as Cadaret and Hartung (2021), Cardoso, Duarte, Gaspar, Bernardo, Janeiro and Santos (2016), and S Savickas and Lara (2016) are examples of research within the Global North context, while Albien (2020), JG Maree, Cook and Fletcher (2018), and Wessels and Diale (2017) conduct their research within the Global South context. The researchers' work from both contexts indicates a growing interest in investigating the benefits of life-design interventions. Lopez Levers, May and Vogel (2011) and JG Maree and Taylor (2016) have underscored the criticism levelled against the application of Global North career counselling theories and intervention in Global South contexts. They argue that researchers working in Global South contexts should do more than adapt and re-standardise specific measures and models from the Global North before they are used in developing countries. However, designing and developing strategies and instruments to address career counselling needs in the Global South is equally important. The researchers (from both the Global South and Global North contexts) affirm that the life-design paradigm can assist in preparing and empowering young people from various countries with skills and knowledge that will help them navigate and thrive in the contemporary world of work. ML Savickas et al. (2009) claim that this type of counselling intervention puts Guichard's (2005) self-construction and ML Savickas' (2005) career-construction theories into practice. Self-construction theory (Guichard, 2005) presumes that individuals actively participate in their self-construction by telling their story in a social context. Participants in our research were predominantly adolescents who were preparing to leave school. Career indecision during adolescence, viewed through the lens of Erikson's theory of psychosocial development, is discussed next.

Career indecision and adolescent development

Erikson's (1968) theory on psychosocial development identifies eight different stages and describes the main psychosocial task as "identity formation" during the adolescent stage. Erikson defines adolescence as the period when children transition into adulthood (12 to 18 years) (Sokol, 2009). During adolescence, appropriate career decision-making is an important developmental activity. While some adolescents experience challenges in making a career decision as passive (they are tagged as undecided), such challenges for others are rather pervasive and pathological (Gati, Gadassi, Saka, Hadadi, Ansenberg, Fiedmann & Asulin-Perets, 2011; Gati & Saka, 2001). For others, the challenges linked with career decision-making arise from other sources. JG Maree (2019) suggests that identity diffusion is among the five different types of career indecision challenges (others include low levels of self-efficacy, dependence, negative attitude and a lack of autonomy) that constitute the basis of considering changing career decisions.

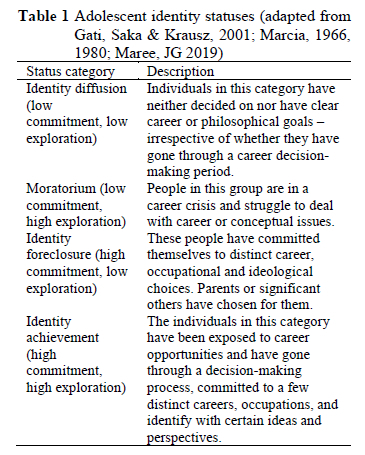

Identity diffusion is one of four different identity statuses, which, according to Marcia (1966, 1980), are ways in which adolescents (those in the later stages) deal with identity issues and identify their career of interest. The four statuses are hinged on the various levels of adolescents' commitment (high or low) to work roles and exploration (via examining of occupational roles). Based on the work of researchers such as Erikson, Marcia's explanation of the statuses is provided in Table 1.

People's subjective career indecision and indecisiveness are often disregarded in marginalised contexts. Consequently, the emphasis is on the indecision or indecisiveness instead of referring to themselves as people with indecision or undecidedness.

The Aim of the Study

With this study we aimed to explore the influence of life-design counselling on learners struggling with career indecision who hail from resource-constrained communities.

Research Questions

The following questions guided the research:

i) How did life-design-based counselling influence learners with career indecision who hail from resource-constrained communities?

ii) How did the participants in the current study experience life-design-based counselling?

Method

A mixed methods approach was conducted in the study but only the qualitative aspect is reported in this article.

Participants and Context

Non-probability, purposive sampling was used in the study reported on here. Participants were chosen based on specific criteria to allow us to engage with the research questions and interact with the dominant themes. The participants were Grade 11 learners from two public schools in a school district familiar to us. It is fair to state that we were knowledgeable about the participants' career challenges and were granted access to the schools. A few criteria had to be met to include participants in the study. The participants had to

• be between the ages of 16 and 21 years,

• be high school learners in Grade 11 at a public school located in a resource-constrained community,

• struggle with career decision-making, and

• be willing to engage in the process of life-design-based counselling.

Mode of Inquiry and Design

Intervention research (Rothman & Thomas, 1994) based on life-design counselling was conducted using a qualitative mode of inquiry. A quasi-experimental pre-test/post-test comparison group design was used to assess the extent of change in career indecision and adaptability of participants exposed to the intervention. The research project represents a qualitative-quantitative mode of inquiry, with equal priority given to both data sets. In this article we report on the qualitative findings.

Data Construction

Qualitative data were generated from interviews, observations, participant journal entries, postmodern techniques (lifeline and drawings) and life-design counselling methods. The Career Interest Profile (CIP) was the main data generation instrument.

Procedure (The Intervention)

Seven intervention sessions, each of approximately 50 minutes, were conducted over a period of 8 weeks. Due to the COVID 19 pandemic, there was an interval of 6 months between the fourth and fifth sessions because schools were shut down to prevent the spread of the virus. Therefore, the first four sessions were held between the middle of February and the middle of March 2020. The last three sessions took place in September 2020.

Table 2 shows the sequence of stages that were followed to generate data, as well as the planned activities of the qualitative intervention.

Quantitative Data Construction

In our study two measures were used to gather quantitative data. The one was the Career AdaptAbilities Scale - South African Form (CAAS-SA) (Maree, JG 2012), and the other was the Career Decision Difficulties Questionnaire (CDDQ) (Gati et al., 2001).

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Braun and Clarke's (2023) six-phase thematic data analysis method was employed. In the first phase, we familiarised ourselves with the data, coded and searched for themes in the second and third phases respectively. The fourth phase consisted of reviewing the subthemes and grouping them into themes. After defining the themes in the fifth phase, the report was compiled and written in the sixth. Specific patterns identified within the data and the identified subthemes and themes that emerged from the data constituted answers to the research questions.

Ethical Considerations

Permission to conduct the research was obtained from the relevant university's institutional review board. Throughout the research project, we adhered to standard ethical considerations: All participants were informed that participation in the project was voluntary and that they could withdraw whenever they wished. We ensured that our role as researchers was not to be confused with that of psychologists. An experienced educational psychologist was made available on-site to attend to any participants who manifested emotional behaviour or trauma due to their participation in the research.

Findings (Results)

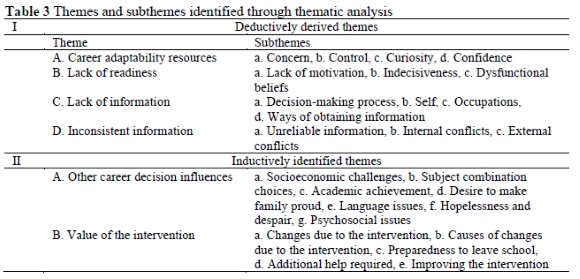

Participants' reflections after having completed the two questionnaires before and after the intervention, the focus-group interviews, as well as life-design techniques were included in the data-gathering process. The categories and subcategories of the quantitative assessment measures used in this research study served as the starting point for identifying themes. Given that mixed methods research encompasses the qualitative approach, we started with anticipated themes (deductive analysis) while keeping an eye on patterns that could constitute emerging themes and subthemes that had not been expected (inductive analysis). Therefore, the approach employed to analyse the data can best be referred to as deductive-inductive. In the process of analysing the data, some additional themes were identified. In all, four themes were deductively derived and two themes were inductively identified from the data (cf. Table 3).

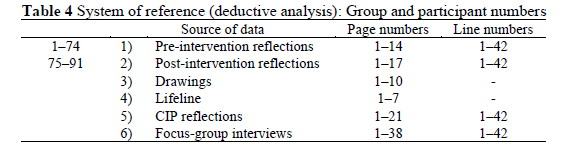

Examples of participants' verbatim responses are provided below to substantiate their perceptions and reflections. A four-digit coding system was employed to report participants' responses from various data sources as is summarised in Table 4.

For example, the code 76;2;3;11 signifies that the respondent is participant number 76 of the intervention group. The data source is the participant's reflective journal after completing the CAAS and CDDQ assessment questionnaires, and the entry is found on page 3, line 11.

Theme 1: Career Adaptability Resources

Hartung (2013:46) describes career adaptability as "a process that includes the development of attitudes, beliefs and competencies to be able to plan careers, investigate career-related options, solve problems effectively and make optimal career decisions." Concern, control, curiosity, and confidence are considered resources for career adaptability.

Concern

This questionnaire for assessment of career adaptability make me start taking my life seriously now because I have been concerned about how am I going to continue it. It also increased my self-awareness as well as self-esteem (84;1;12;35-37).

Control

Looking at these questions somethings came to my mind that I have to be very clear about what I do today can always be affective to my future. And I should always have control of my life and decisions (80;1;12;12-14).

Curiosity

Judging from now I never explore my surroundings and observe other ways of doing things (77;2;14;33-35).

Confidence

When I was answering these questions, I feel so confident about my future. The fact that I didn't know how my future will be (80;1;12;12-14).

Theme 2: Readiness

A lack of readiness refers to difficulties that occur before the decision-making process. These include lack of motivation to get involved in the decision-making process, general indecisiveness about all types of decisions, and dysfunctional beliefs about decision-making (Gati et al., 2001).

What has changed since we started? Before, I was so confused, I didn't know after my matric what I am going to do, like to study and stuff like that, not because I don't know what to do, but because I am good at many things. Like I am so confused I didn't know what to choose and what I could choose ... but after we did the questionnaires, I have realised my strength and weaknesses. (82;6;3;10-15)

Theme 3: Lack of Information

As Gati et al. (2001) explain, a lack of information as a source of career decision-making difficulties is related to a lack of knowledge about the process, lack of information about self, lack of information about occupation, and lack of information about ways of obtaining additional information.

I think I need to be confident with the decisions that I made, to know who I am, the real me (90;2;17;18). My problem is that am so addicted to rap but it's not a career and that's what I want to do (82;5;11;2-3).

Theme 4: Inconsistent Information

Three categories of difficulties about the use of information resort under inconsistent information. These are unreliable information (difficulties arising from unreliable or ambiguous information), internal conflicts (difficulties caused by contradicting preferences), and external conflicts (difficulties caused by contradictory interaction with significant others) (Gati et al., 2001).

I already choose my career. I know it and understand but some people they are not supporting me like my family and friends, they say it's not a good career for me, I must choose better one (83;2;15;40-41).

Theme 5: Other Career Decision Influences This theme mostly covered other career influences such as socioeconomic challenges, choices about subject combinations, academic achievement, a desire to make the family proud, language issues, hopelessness and despair, and psychosocial issues.

Not being able to speak English properly (89;5;19;20).

I already choose my career. I know it and understand but some people they are not supporting me like my family and friends, they say it's not a good career for me, I must choose better one. The problem is that I don't even have money to go to the varsity, that's the big problem for myself. (83;2;15;40-42)

I grow up without a father and there was no guide to tell about life (90;5;20;3-4).

My father left us and we were struggling because my mother was not working and my father was not helping (79;5;6;23-24).

Theme 6: Value of the Intervention

Participants' perceptions of the intervention are reported under this theme. They include changes due to the intervention, causes of changes due to the intervention, preparedness to leave school, additional help required, and improving the intervention.

The thing that has changed is that I am now able to make my career and the thing that I didn't know that I am the only one who can make my career choice. I now know where my life is going. (80;5;9;2-3) The story of my life is the one that changed everything, cause now I can think like someone who has a future to prepare for without a doubt (80;5;9;8-9).

You must attend/meet learners frequently in a way that they will be . they will have confident on school (89;6;34;4-5).

Discussion

This research was conducted in response to calls by scholars in the field of career counselling for more empirical studies on the topic. We departed from the premise that high school learners from resource-poor communities require support to think about their future, decide what they intend to do when they leave school, and develop the resources that are needed to adapt to the changing world of work (Hartung, Porfeli & Vondracek, 2005; Watson & McMahon, 2005). We aimed to explore the influence of life-design-based counselling on high school students with career indecision who hail from resource-constrained communities. The research questions were:

i) How did life-design-based counselling influence learners with career indecision who hail from resource-constrained communities?

ii) How did the participants in the current study experience life-design-based counselling?

These two questions are discussed in the following sections.

How did Life-design-based Counselling Influence Learners with Career Indecision who Hail from Resource-constrained Communities? We observed what Schwartz, Ward, Monterosso, Lyubomirsky, White and Lehman, (2002:1179) described as "choice maximising anxiety" (the more anxious and obsessed people become with maximising their choices, the more they are inclined to execute choices that make them feel worse) among the participants. In our research, the participants were seeking the "best" career options, and, paradoxically, many of them were left confused because they experienced more difficulty in deciding. To some extent, the findings from our study resonate with those of Grier-Reed and Skaar (2010), who researched the effect of a constructivist career course on college students in the United States. Participants' self-efficacy regarding career decision had improved but career indecision measured after the intervention was not less.

Assisting young people with interventions that can enhance their self-efficacy and help them better understand who they are is important in helping them move on in career decision-making (Savickas, ML 2001; Super, 1957). Furthermore, the literature provides evidence that self-efficacy is among the important career barriers that adolescents in resource-scarce environments face (or perceive) when choosing or aspiring for future careers (Alexander, Seabi & Bischof, 2010; Hendricks, Savahl, Mathews, Raats, Jaffer, Matzdorff, Dekel, Larke, Magodyo, Van Gesselleen & Pedro, 2015; Maree, JG & Che, 2020). This finding is supported by the findings in our study, Participants in our study were involved in activities that put them in a position to understand themselves better and acquire self-knowledge "...knowing more about my career is what has changed about my career is understanding my strengths and my weaknesses" (75;4;2;4-5). Another response was: "... today's session made my life easy. Now I know who I am. I should stay true and have trust in me" (77;4;5;6-7).

Going by Super's (1957, 1990) findings, participants in our study began the process of constructing their careers through acquiring self-knowledge. Knowledge about the self would assist the participants in responding to questions such as, "Who am I?" (Hartung et al., 2005). Attempts by participants in our study to answer the afore-mentioned question regarding their identity exemplify what Super (1983) refers to as the active exploration in which adolescents engage during the curiosity stage of career development.

Most young people do not have adequate career information and are inclined to depend on adults for such information (Del Corso & Briddick, 2015). JG Maree, Cook, et al. (2018) highlight the importance and benefits of providing (disadvantaged) learners (especially) with appropriate information about careers. In addition, Del Corso and Briddick (2015:362) found that some adolescents regarded such information as "fact", failed to question it or verify its validity - yet, they still benefited from the intervention. In our study, participants were exposed to career information included in one of the assessment measures used in the intervention, namely the CIP. The reaction of Participant 89 of the intervention group is an example of how exposure to career information assisted in alleviating her difficulties with career decidedness. She stated her goal as to what she hoped to achieve at the end of the intervention as follows: "At the end I should be able to choose my career without struggling to choose it. I must also know what to do when I am struggling with my future and solve my career problems. Help me gain confidence to achieve everything I want to do, and also, guide me through the way I want to read my Grade 11 so that I can get a bursary" (89;4;18;29-32). The same participant (89) reflected as follows after completing the CIP: "While I was going through the CIP, I realised that I did not know much about the career choice and also about the career category, and the work you do and also the jobs on that type of career category. I also underestimated other careers because I did not know the jobs of that career. And work through them, and I also have to know myself for me to be able to choose a career. I have to change my home situation, change gives me confidence on how to work on my challenges" (89;4;19;23-27) This finding is in line with Abrams, Lee, Brown and Carr (2015) and Roche, Carr, Lee, Wen and Brown (2017) who point out the significance of culture in career decision-making with individuals from Eastern cultures who had salient concerns regarding their need for information at the beginning of their career exploration process. Participants in our study hailed from disadvantaged backgrounds where access to career information was limited and could hinder their decisions about their careers.

The positive changes reflected by the participants indicate that they benefited to some degree from the intervention regarding the category about inconsistent information. This finding is consistent with Lieff's (2009) findings that career decision-making is enhanced when counsellors facilitate the process assisting clients to reflect on their strengths, areas for development, and work values. The findings are in line with those of a study conducted with university students in Italy by Di Fabio and Maree (2012) and another study with students in Iran (Pordelan, Hosseinian & Lashaki, 2021). The results from these studies show that counselling for career-construction intervention enhances career decision-making self-efficacy and resilience, and reduces career decision-making difficulties. Individuals' indecision is also understood in terms of the stories they tell and not only from psychometric measures (Stead & Watson, 2017). These stories, narrated by the client and reflected on by the counsellor, mirror the clients' central life theme and its relationship to career indecision. The client's past, present and future are captured in these stories. Stead and Watson (2017) agree that the narrative approach underscores the importance of the meaning derived from stories and they argue that one's career problems can only be meaningfully and coherently understood if they are linked to one's life theme.

Feelings of uncertainty and insecurity apparently still hindered the decision-making process for some of the participants - probably because of their beliefs at the time the research was conducted. This situation is understandable, given the definition of work in this context as an activity primarily oriented towards survival rather than self-fulfilment.

How did the Participants in the Current Study Experience Life-design-based Counselling?

• The reader is advised that this research question, although only referring to "career indecision", also refers to "career adaptability." Here we concur with Hartung and Cadaret (2017) and Nota et al. (2016), who agree that enhancing people's career adaptability contributes to a decrease in their career indecision. Participants clearly displayed signs of self- and career construction and started to verbalise plans for their future in their post-intervention reflections, as described by ML Savickas et al. (2009). The findings in our study support the results of research conducted by JG Maree, Cook, et al. (2018) involving Grade 11 participants from a private school and a low-resourced public school. JG Maree, Cook, et al. (2018) report positive qualitative adaptability results for participants from the public school but not for those from the private school. The findings in our study divergence from some aspects of another study by JG Maree, Pienaar and Fletcher (2018) on a life-design counselling intervention programme conducted to improve the sense of self of participants who attended an affluent independent school for girls. In this study positive qualitative results were not recorded. JG Maree, Pienaar, et al. (2018) found that their intervention was not successful (as expected) in enhancing aspects of the participants' career adaptability, such as taking control of their future. Results of our study concur with the findings of a qualitative case study by Setlhare-Meltor and Wood (2016) in which narrative intervention assisted an adolescent participant in designing and narrating a different future as another possibility or choice. Setlhare-Meltor and Wood's (2016) study was conducted with a formerly homeless participant.

Participation in the programme seemed to have helped those involved in our research to take control, become more responsible for their own success, and work towards realising their future aspirations. It can be stated that our study confirms the emphasis by other researchers (Fritz & Beekman, 2007; Watson, McMahon, Foxcroft & Els, 2010) that career counselling clients with decision-making difficulties become aware of alternative opportunities and prospects when they were skilfully guided towards subjective meaning-making. The following example indicates that exposure to the intervention programme allowed participants to go through a reflexive process, suggesting that they became more aware of who they were, what was important to them, and what was preventing them from achieving their career goals.

I have been thinking a lot about my future and taking all the information that I give you about myself. Putting it together and I have seen that really, I want that career and for my plan B if I don't get to study Law, I can study to be a social worker as long as it deals with helping people who are in need and giving something positive out of what I do. (80;2;15;18-21).

Participants reported how they had been engaged in exploring information about who they were (their identity) and the careers they aspired to pursue. Such exploratory behaviour about the self and occupations was evident in participants' reflections in the post-intervention assessment, suggesting that the intervention programme motivated them to engage further in exploratory behaviour. This finding agrees with the statistically significant difference in the pre-/post-intervention scores of the intervention group (Jude, Maree & Jordaan, 2023). One of the participants in the intervention group before and after the intervention responded as follows: "The reason for my thoughts is that I have to make some investigation before I make choice. It's hard to make investigation because we sometimes found different answers and I will start to be confused" (91;1;14;1-3), and "I had a problem of choosing only one career not knowing what obstacles will I face, for example, there will be a time where my points will not manage to be qualified for that career then I will have to choose another career. Career categories helped me to think about other careers for example marketing. I found it more interesting, and I want to make it or achieve if (91;4;21;16-19). This finding concurs with that of Rehfuss (2009), who found that such changes are expected as individuals begin to embrace and enact career exploration and specification. All the participants reported initiating their own career exploration activities or further investigation for some, following the life-design intervention.

Our interaction with the participants was informed by understanding adolescents' career aspirations and an awareness of the aspects that influenced their career choices and decision-making. In as much as participants should make their own decisions about their future career journeys and aspirations, focusing on self and career construction would be beneficial to attain lower levels of career indecision. Most participants reported enhanced motivation (both in deciding on a career and in their studies), self-regulation, time management, study skills, improved academic achievement and enhanced work ethic. They reported having initiated career exploration once they had participated in the life-design intervention. This finding concurs with the finding by Hirschi (2009), who concludes that adaptive individuals also feel empowered and also by ML Savickas (2011), who states that concern (for one's future) develops in response to the individual making connections between their past, present, and future.

Through the acquisition of self-knowledge, the intervention enhanced participants' sense of attending school and being persistent and patient to achieve their future goals through hard work. Participants became aware that they had made wrong subject choices that would not lead to their dream careers, that their current academic achievement was inadequate to secure a place at a tertiary institution, and that community and family influence left them helpless and desperate. However, their responses during the focus-group interview created a different perspective, as the intervention seemingly positively impacted the participants. The career intervention programme apparently facilitated a shift in the participants' thinking regarding how they decided about their future, albeit marginally. The study results demonstrate reduced indecisiveness and the development of intentionality. The latter is one of life-design counselling goals, as participants accorded priority to their schoolwork and engaged in activities that validated who they were and what was important to them. They stated clear future and possible alternatives of what they intended to do after they left school. This finding supports Rossier's (2015) assertion about the importance of thorough vocational planning to facilitate converting people's intentionality into action and forward movement regarding appropriate and successful career choices.

Limitations of the Study

The following factors are considered limitations of our study. Firstly, the participants in the intervention group were selected purposively (non-random), which implies that it will not be possible to generalise findings to the South African population.

Secondly, the learners who participated in this study hailed from a homogenous background in a rural setting, which raises the question of what the results would have been if the study had been conducted in a resource-constrained community within an urban setting. Thirdly, the subjective nature of the qualitative data necessitated subjective interpretation and analysis, which, according to Darlington and Scott (2003), raises doubt on how valid participants' views and opinions could be. Lastly, familiarity with the context in which the study was conducted could lead to our biased judgment, even though steps were taken to avoid the possibility of halo or horn effects.

Recommendations for Theory Development, Research, and Practice

Firstly, assisting learners across the diversity continuum (as early as in Grade 9) to start exploring their identities will be of great value to prepare them to make subject choices, lay the foundation for making appropriate career choices, and transitioning successfully from school to work/further studies by the time they reach Grade 12. Secondly, participants from diverse backgrounds should be considered in future research initiatives. Thirdly, involving small and large groups of people in future research to further explore the value for and influence of life-design counselling on learners struggling with career indecision is important. In the fourth place, including different data-gathering strategies, assessment techniques, and instruments should be considered in future research. In the fifth place, policymakers in the education sector should consider integrating this approach (life-design intervention) into the curriculum to help learners become more adaptable, link academic knowledge with the purposes of school learning, and prepare them to become employable. Lastly, continually updating and upskilling life orientation teachers and vocational psychologists to ensure that they stay abreast of developments in the field of career counselling. Being able to address learners' contemporary career counselling needs is a key requisite for facilitating an avant garde career counselling service to all learners.

Conclusion

The influence of life-design counselling intervention on high school learners with career indecision was explored in an effort to address the challenge of appropriate career development approaches with previously disadvantaged populations in SA. Life-design counselling techniques mediate the career indecision of learners from resource-constrained communities to varying degrees. Participation in the intervention helps them to take their studies seriously, and to become aware of their strengths and areas for growth. To a certain extent, it helps them make realistic choices and take concrete action towards constructing a future career trajectory.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants for participating in the study. We also thank Mrs Isabel Claassen for her editing of the text.

Authors' Contributions

Che Jude and Kobus Maree co-wrote the manuscript. Che Jude conducted the intervention with participants. Both authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Notes

i. In this article the term "marginalised" means the same as resource-constrained.

ii. This article is based on Che Jude's doctoral dissertation.

iii. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Abrams MD, Lee IH, Brown SD & Carr A 2015. The career indecision profile: Measurement equivalence in the United States and South Korea. Journal of Career Assessment, 23(2):225-235. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072714535028 [ Links ]

Acevedo VE & Hernandez-Wolfe P 2014. Vicarious resilience: An exploration of teachers and children's resilience in highly challenging social contexts. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 23(5):473-493. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2014.904468 [ Links ]

Akhurst J & Mkhize NJ 2006. Career education in South Africa. In GB Stead & MB Watson (eds). Career psychology in the South African context (2nd ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Albien AJ 2020. Exploring processes of change in a life-design career development intervention in socio-economically challenged youth. Journal of the National Institute for Career Education and Counselling, 45(1):6-14. https://doi.org/10.20856/jnicec.4502 [ Links ]

Alexander D, Seabi J & Bischof D 2010. Efficacy of a post-modern group career assessment intervention of disadvantaged high school learners. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 20(3):497-500. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2010.10820405 [ Links ]

Arora R & Rangnekar S 2016. Moderating mentoring relationships and career resilience: Role of conscientiousness personality disposition. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 31(1):19-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/15555240.2015.1074052 [ Links ]

Bischof D & Alexander D 2008. Post-modern career assessment for traditionally disadvantaged South African learners: Moving away from the 'expert opinion'. Perspectives in Education, 26(3):7-17. Available at https://www.ajol.info/index.php/pie/article/view/76478. Accessed 29 February 2024. [ Links ]

Blustein DL, Franklin AJ, Makiwane M & Gutowski E 2017. Indigenisation of career psychology in South Africa. In GB Stead & MB Watson (eds). Career psychology in the South African context (3rd ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Blustein DL, McWhirter EH & Perry JC 2005. An emancipatory communitarian approach to vocational development theory, research, and practice. The Counseling Psychologist, 33(2): 141-179. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000004272268 [ Links ]

Braun V & Clarke V 2023. Toward good practice in thematic analysis: Avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing researcher. International Journal of Transgender Health, 24(1):1-6. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2022.2129597 [ Links ]

Cadaret MC & Hartung PJ 2021. Efficacy of a group career construction intervention with urban youth of colour. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 49(2): 187-199. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2020.1782347 [ Links ]

Cardoso P, Duarte ME, Gaspar R, Bernardo F, Janeiro IN & Santos G 2016. Life Design Counseling: A study on client's operations for meaning construction. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 97:13-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjvb.2016.07.007 [ Links ]

Cochran LR 2011. The promise of narrative career counseling. In K Maree (ed). Shaping the story: A guide to facilitating narrative counselling. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004406162_003 [ Links ]

Darlington Y & Scott D 2003. Qualitative research in practice: Stories from the field of social work education. The International Journal, 22(1):115-118. [ Links ]

Del Corso J & Rehfuss MC 2011. The role of narrative in career construction theory. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(2):334-339. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjvb.2011.04.003 [ Links ]

Del Corso JJ & Briddick HS 2015. Using audience to foster self-narrative construction and career adaptability. In PJ Hartung, ML Savickas & WB Walsh (eds). APA handbook of career intervention (Vol. 2). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14439-019 [ Links ]

Di Fabio A & Maree JG 2012. Group-based Life Design Counseling in an Italian context. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1):100-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjvb.2011.06.001 [ Links ]

Duarte ME 2009. The psychology of life construction. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75(3):259-266. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjvb.2009.06.009 [ Links ]

Erikson EH 1968. Identity: Youth, and crisis. New York, NY: W.W. Norton. [ Links ]

Freeman SC 1993. Donald Super: A perspective on career development. Journal of Career Development, 19(4):255-264. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01354628 [ Links ]

Fritz E & Beekman L 2007. Engaging clients actively in telling stories and actualizing dreams. In K Maree (ed). Shaping the story: A guide to facilitating narrative counselling. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Gati I, Gadassi R, Saka N, Hadadi Y, Ansenberg N, Friedmann R & Asulin-Peretz L 2011. Emotional and personality-related aspects of career decision-making difficulties: Facets of career indecisiveness. Journal of Career Assessment, 19(1):3-20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072710382525 [ Links ]

Gati I & Saka N 2001. High school students' career-related decision-making difficulties. Journal of Counseling & Development, 79(3):331 -340. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2001.tb01978.x [ Links ]

Gati I, Saka N & Krausz M 2001. Should I use a computer-assisted career guidance system? It depends on where your career decision-making difficulties lie. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 29(3):301-321. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880120073021 [ Links ]

Grier-Reed TL & Skaar NR 2010. An outcome study of career decision self-efficacy and indecision in an undergraduate constructivist career course. The Career Development Quarterly, 59(1):42-53. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2010.tb00129.x [ Links ]

Guichard J 2005. Life-long self-construction. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 5(2): 111-124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-005-8789-y [ Links ]

Hart A, Gagnon E, Eryigit-Madzwamuse S, Cameron J, Aranda K, Rathbone A & Heaver B 2016. Uniting resilience research and practice with an inequalities approach. Sage Open, 6(4):1 -13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016682477 [ Links ]

Hartung PJ 2013. Career construction counselling. In A Di Fabio & JG Maree (eds). Psychology of career counselling: New challenges for a new era. New York, NY: Nova. [ Links ]

Hartung PJ & Cadaret MC 2017. Career adaptability: Changing self and situation for satisfaction and success. In K Maree (ed). Psychology of career adaptability, employability and resilience. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66954-0 [ Links ]

Hartung PJ, Porfeli EJ & Vondracek FW 2005. Child vocational development: A review and reconsideration. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66(3):385-419. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjvb.2004.05.006 [ Links ]

Hendricks G, Savahl S, Mathews K, Raats C, Jaffer L, Matzdorff A, Dekel B, Larke C, Magodyo T, Van Gesselleen M & Pedro A 2015. Influences on life aspirations among adolescents in a low-income community in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 25(4):320-326. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2015.1078089 [ Links ]

Hirschi A 2009. Career adaptability development in adolescence: Multiple predictors and effect on sense of power and life satisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(2): 145-155. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjvb.2009.01.002 [ Links ]

Jude C, Maree JG & Jordaan J 2023. Effects of life design counselling on secondary students with career indecision in a resource-constrained community. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 28(1):2245439. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2023.2245439 [ Links ]

Lieff SJ 2009. Perspective: The missing link in academic career planning and development: Pursuit of meaningful and aligned work. Academic Medicine, 84(10):1383-1388. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b6bd54 [ Links ]

Lopez Levers L, May M & Vogel G 2011. Research on counseling in African settings. In E Mpofu (ed). Counseling people of African ancestry. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. Marcia JE 1966. Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3(5):551-558. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0023281 [ Links ]

Marcia JE 1980. Identity in adolescence. In J Adelson (ed). Handbook of adolescent psychology. New York, NY: Wiley. [ Links ]

Maree JG 2012. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale-South African Form: Psychometric properties and construct validity. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 80(3):730-733. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjvb.2012.01.005 [ Links ]

Maree JG 2016a. Career construction counseling with a mid-career Black man [Special issue]. The Career Development Quarterly, 64(1):20-34. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12038 [ Links ]

Maree JG 2016b. Career Interest Profile (CIP) version 5. Randburg, South Africa: JvR Psychometrics. [ Links ]

Maree JG 2017. Opinion piece: Using career counselling to address work-related challenges by promoting career resilience, career adaptability, and employability [Special issue]. South African Journal of Education, 37(4): 1-5. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v37n4opinionpiece [ Links ]

Maree JG 2019. Group career construction counselling: A mixed-methods intervention study with high school students. The Career Development Quarterly, 67(1):47-61. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12162 [ Links ]

Maree JG & Che J 2020. The effect of life-design counselling on the self-efficacy of a learner from an environment challenged by disadvantages. Early Child Development and Care, 190(6):822-838. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2018.1495629 [ Links ]

Maree JG, Cook AV & Fletcher L 2018. Assessment of the value of group-based counselling for career construction. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 23(1 ):118-132. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2017.1309324 [ Links ]

Maree JG, Pienaar M & Fletcher L 2018. Enhancing the sense of self of peer supporters using life design-related counselling. South African Journal of Psychology, 48(4):420-433. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246317742246 [ Links ]

Maree JG & Taylor N 2016. Development of the Maree Career Matrix: A new interest inventory. South African Journal of Psychology, 46(4):462-476. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246316641558 [ Links ]

Maree N & Maree JG 2021. The influence of group life-design-based counselling on learners' academic self-construction: A collective case study. South African Journal of Education, 41(3):Art. #2051, 16 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v41n3a2051 [ Links ]

Masten AS 2014. Global perspectives on resilience in children and youth. Child Development, 85(1):6-20. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12205 [ Links ]

Nota L, Santilli S & Soresi S 2016. A life-design-based online career intervention for early adolescents: Description and initial analysis [Special issue]. The Career Development Quarterly, 64(1):4-19. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12037 [ Links ]

Pordelan N, Hosseinian S & Lashaki AB 2021. Digital storytelling: A tool for life design career intervention. Education and Information Technologies, 26(3):3445-3457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10403-0 [ Links ]

Rankin NA & Roberts G 2011. Youth unemployment, firm size and reservation wages in South Africa. South African Journal of Economics, 79(2): 128- 145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1813-6982.2011.01272.x [ Links ]

Rehfuss MC 2009. The future career autobiography: A narrative measure of career intervention effectiveness. The Career Development Quarterly, 58(1 ):82-90. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2009.tb00177.x [ Links ]

Roche MK, Carr AL, Lee IH, Wen J & Brown SD 2017. Career indecision in China: Measurement equivalence with the United States and South Korea. Journal of Career Assessment, 25(3):526- 536. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072716651623 [ Links ]

Rossier J 2015. Career adaptability and life designing. In L Nota & J Rossier (eds). Handbook of life design: From practice to theory and from theory to practice. Ashland, OH: Hogrefe Publishing. [ Links ]

Rothman J & Thomas EJ (eds.) 1994. Intervention research: Design and development for human service. New York, NY: Haworth Press. [ Links ]

Rottinghaus PJ, Falk NA & Eshelman A 2017. Assessing career adaptability. In K Maree (ed). Psychology of career adaptability, employability and resilience. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66954-0 [ Links ]

Savickas ML 2001. The next decade in vocational psychology: Mission and objectives. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 59(2):284-290. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1834 [ Links ]

Savickas ML 2005. The theory and practice of career construction. In SD Brown & RW Lent (eds). Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Savickas ML 2008. David V. Tiedeman: Engineer of career construction. The Career Development Quarterly, 56(3):217-224. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2008.tb00035.x [ Links ]

Savickas ML 2011. Constructing careers: Actor, agent, and author. Journal of Employment Counseling, 48(4):179-181. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1920.2011.tb01109.x [ Links ]

Savickas ML 2013. The 2012 Leona Tyler award address: Constructing careers-actors, agents, and authors. The Counseling Psychologist, 41(4):648- 662. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000012468339 [ Links ]

Savickas ML 2015a. Career counselling paradigms: Guiding, developing, and designing. In PJ Hartung, ML Savickas & WB Walsh (eds). APA handbook of career intervention (Vol. 1). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14438-008 [ Links ]

Savickas ML 2015b. Life-design counseling manual. Rootstown, OH: Vocopher. Available at https://www.wc.k12.wi.us/cms_files/resources/savickas%20life%20design%20manual.pdf. Accessed 29 February 2024. [ Links ]

Savickas ML 2019. Career counselling (2nd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Savickas ML, Nota L, Rossier J, Dauwalder JP, Duarte, ME, Guichard J, Soresi S, Van Esbroeck R & Van Vianen AEM 2009. Life designing: A paradigm for career construction in the 21st century. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 75(3):239-250. https://doi.org/10T016/jjvb.2009.04.004 [ Links ]

Savickas S & Lara T 2016. Lee Richmond: A life designed to take the counseling profession to new places [Special issue]. The Career Development Quarterly, 64(1):75-82. https://doi.org/101002/cdq.12042 [ Links ]

Schwartz B, Ward A, Monterosso J, Lyubomirsky S, White K & Lehman DR 2002. Maximizing versus satisficing: Happiness is a matter of choice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(5):1178-1197. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.5.1178 [ Links ]

Setlhare-Meltor R & Wood L 2016. Using life design with vulnerable youth [Special issue]. The Career Development Quarterly, 64(1):64-74. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12041 [ Links ]

Sokol JT 2009. Identity development throughout the lifetime: An examination of Eriksonian theory. Graduate Journal of Counseling Psychology, 1(2):139-148. Available at https://epublications.marquette.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1030&context=gjcp. Accessed 29 February 2024. [ Links ]

Stead GB & Watson M 2017. Career decision-making and career indecision. In GB Stead & M Watson (eds). Career psychology in the South African context (3rd ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Stead GB & Watson MB 1998. Career research in South Africa: Challenges for the future. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 52(3):289-299. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1997.1627 [ Links ]

Super DE 1957. The psychology of careers. New York, NY: Harper. [ Links ]

Super DE 1983. Assessment in career guidance: Toward truly developmental counseling. The Personnel and Guidance Journal, 61(9):555-562. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2164-4918.1983.tb00099.x [ Links ]

Super DE 1990. A life-span, life-space approach to career development. In D Brown & L Brooks (eds). Career choice and development: Applying contemporary theories to practice (2nd ed). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Theron LC 2017. Facilitating adaptability and resilience: Career counselling in resource-poor communities in South Africa. In K Maree (ed). Psychology of career adaptability, employability and resilience. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66954-0 [ Links ]

Watson M 2013. Deconstruction, reconstruction, co-construction: Career construction theory in a developing world context. Indian Journal of Career and Livelihood Planning, 2(1):3-14. Available at https://jivacareer.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/2-Mark-Watson-Formatted.pdf. Accessed 29 February 2024. [ Links ]

Watson M & McMahon M 2005. Editorial: Part 1. Postmodern (narrative) career counselling and education. Perspectives in Education, 23(2):vii-ix. [ Links ]

Watson M, McMahon M, Foxcroft C & Els C 2010. Occupational aspirations of low socioeconomic black South African children. Journal of Career Development, 37(4):717-734. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845309359351 [ Links ]

Wessels CJJ & Diale BM 2017. Facebook as an instrument to enhance the career construction journeys of adolescent learners [Special issue]. South African Journal of Education, 37(4):Art. # 1470, 12 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v37n4a1470 [ Links ]

Received: 21 November 2022

Revised: 15 August 2023

Accepted: 8 November 2023

Published: 29 February 2024