Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.43 suppl.2 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v43ns2a2193

ARTICLES

Top management and teacher involvement in the strategic planning process in Zimbabwean schools

Victor C Ngwenya

Department of Educational Leadership and Management, Faculty of Education, College of Economic and Management Sciences, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa and Zimbabwe Open University, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe victor.ngwenya@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

In this study I investigated the involvement of top management and teachers in the strategic planning process in 5 district schools located in the Bulawayo Metropolitan Province guided by the Take Stock Analysis (TSA) model. The constructivist/interpretivist paradigm was the qualitative methodology adopted for the study using a case study research method. The participants were 5 education managers and 5 focus groups of 4 teachers, each purposively selected from each school as an in-depth analysis of the phenomenon was sought through face-to-face interviews. Interview data were inductively and thematically analysed while strategic plans provided were inspected using content analysis and supplemented with interview data. The findings were reported following the concept of strategic planning, the formulation, monitoring and evaluation process. The results reveal that some schools used the centralised or decentralised strategic planning process while others hired strategists with minimal involvement from the teachers and the top management of the school. I recommend that stakeholders are actively involved in the entire strategic planning process to enhance ownership and commitment at the operational level. Most importantly, joint periodic evaluations are needed for modification purposes and relevance.

Keywords: adjustments; centralised; constructivism; decentralised; goals; mission; plan; prioritisation; strategists; vision

Introduction

The hyper competitive edge necessitated by the global economic recession, increasing legislation and technological trends in the education fraternity puts pressure on schools. Internal systems are needed to enable stakeholders to develop a proactive stance in the environment of radical changing demands and declining resources as they map the way forward (Kukreja, 2013). Most post-independent Zimbabwean schools grew in size and complexity due to the social demand for education. This gave rise to the need to continuously keep schools abreast of changes, and efficient and effective through strategic planning (Maleka, 2014). In Zimbabwe, as elsewhere, power in schools was traditionally centralised and the strategic planning process was a prerogative of headquartered personnel (Albon, Iqbal & Pearson, 2016). Of late, the Zimbabwean government has decentralised decision-making powers from the macro level to schools through devolution, thus giving them extensive executive powers (Government of Zimbabwe [GoZ], 2013). This, therefore, calls for "an iterative nature of planning ... inclusive processes that involve multiple stakeholders and promote coherence between planning and implementation" (Albon et al., 2016:219). The involvement of multiple stakeholders, in particular top management (the education manager, the deputy, governing body, heads of departments, senior teachers) and teachers in the crafting of a strategic plan generates shared governance and ownership in the process, which are essential elements in sustaining the plan and change process (Rutherford, 2015). Once strategic decisions have been made, they have strategic implications and schools with strategic plans, in response to rapid changes in technologies and markets, engage in quick fixes (Maleka, 2014). This approach is in contrast to the past practice that relies heavily on hired consultants (Martins, 2024). With this study I, therefore, investigated the involvement of top management and teachers in the strategic planning process in schools in the Bulawayo Metropolitan Province of Zimbabwe. Since strategic planning is a new phenomenon in Zimbabwean schools and strategic plans are demanded by the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education (MoPSE) for accountability and assessment purposes as quality education is sought, I explored the involvement of top management and teachers in the strategic planning process.

Background to the Study

History has documented evidence of people devising ways of outsmarting and outperforming one another in a game of survival of the fittest (Wall, 2016). In the military context that survival depends on strategy, which means the art or science of leading military troops (Stoner, Freeman & Gilbert, 2008). Effectively, as part of his many duties, a Greek general was supposed to lead his army, win battles, hold territories and protect cities from invasion (Stoner et al., 2008). Each objective required a different deployment of resources. In that regard, a military strategy would be defined as a pattern of actual actions that the general took in response to enemy threats (Stoner et al., 2008). However, strategic planning conducted in military operations and the type of military administration used, although efficiently integrating the attainment of both the long and short-term mission, is inappropriate for public learning institutions (Hinton, 2012). Despite that obstacle, the planning and decision-making components were adopted with variation in the 1990s for use in learning institutions for external accountability purposes and assessment (Hinton, 2012).

Business scholars, who were intrigued by the victories scored by the military by way of strategy, borrowed this term first and applied it to the corporate world with commendable results (Rutherford, 2015). Contemporary scholars emulating the business enterprise sought to utilise this concept in schools (Martins, 2024) as well. During the 1990s, strategic planning began to gain currency in higher institutions of learning in the United States of America (USA) when external accountability and assessment plans were demanded for accreditation purposes (Hinton, 2012). Eventually, the strategic planning scope widened to include hospitals and educational institutions. In that context, strategy usually centred on delivering goals to satisfy the political process and producing conspicuous efficiency and value for money to reassure taxpayers (Maleka, 2014).

Literature Review

Literature on the topic reveals that a school's strategy is based on the philosophy of the top management, its mission and the related goals to be achieved (Maleka, 2014). Furthermore, research and evaluation of factors in the external environment within which it functions and its external systems result in the amalgamation of its activities and factors in the external environment (Maleka, 2014). For those reasons, strategic plans used in corporate contexts are vastly different from those used in schools. Johnson and Scholes (2002, in Maleka, 2014:5-6) define a strategy as "the direction and scope of an organisation over the long-term which achieves advantage for the organisation through its configuration of resources within a challenging environment, to meet the needs of markets and to fulfil stakeholder expectations." Rutherford (2015) views it as a deliberate and purposeful action, which reacts to unanticipated developments, fresh market conditions, competitive pressures and collective learning of the organisation over time. Therefore, in an educational context, strategy would entail the mobilisation and utilisation of resources within the school's budgetary constraints and the deployment of human capital for the ultimate purpose of achieving the current and future goals with the hope of satisfying and gratifying the learners. This thrust makes it an organisational compass or road map that drives and guides the school's activities in a collaborated and coordinated manner as it ventures into the competitive and unpredictable future (Kukreja, 2013).

Stated differently, a strategy is a plan of action that is goal directed, policy driven, resource oriented, competitive, advanced and is born out of a detailed strategic planning process. With this in mind, it becomes an instrument that top management use to translate the vision, mission statement, values and goals of the school into reality (Wall, 2016). For the school to have a sustainable competitive advantage over its rivals, it must be unique and place the planning process at the centre (Albon et al., 2016).

Planning

Since planning is a prerequisite in the management process (planning, organising, leading and controlling - POLC), strategists view it as the "locomotive that drives the train of organising, leading and controlling" (Stoner et al., 2008:161). For that reason, planning must be rational and deliberate in its attempt to map out the school's future. Little wonder that Stoner et al. view it as "the process of setting goals and choosing the means to achieve those goals" (2008:265), affirming that planning is fundamental in formulating a strategic plan of a school, which in turn, becomes its blueprint. Therefore, top management and teachers must be actively involved in the strategic planning process if the strategic plan is to be successfully implemented in schools.

Strategic plan

Sallis (2005:124) perceives a strategic plan as a "corporate or institutional developmental plan, which details the measures which the institution intends to take to achieve its mission." This perception enables top management in their management function to organise, lead and control their subordinates into a compatible whole (Stoner et al., 2008). However, the planning process must not be a once-off event with distinctive boundaries but an on-going process that responds to stiff competition and technological advancement in the unpredictable environment they operate in. Thus, planning demands regular reviews to deal with the fast-changing markets (Fernandes, 2018). Most importantly, top management and teachers must know that the strategic plan constitutes the school's development plan (SDP). In this context the SDP is a detailed strategic improvement planning document, born out of the strategic planning process and covers all the prioritised deliverables or school activities (e.g., academic excellence or capital projects), which need to be achieved over a specified period (Xaba, 2006). It also spells out how resources will be committed to such activities and how the targets set are going to be measured (Xaba, 2006). Put in a nutshell, it is the implementation plan (Hinton, 2012).

Strategic planning

Strategists assert that strategic planning is daunting and robust if it is to produce a living strategic document that is responsive to the technological developments and markets of the time (Fernandes, 2018). Similarly, they bemoan the situation when the detailed documents produced through such great effort are not put into practice after they have been duly acknowledged only to gather dust and languish on shelves (OnStrategy, 2021). In Maleka's (2015:14) perception, strategic planning is used to "set the organisational vision, determine the strategies required to achieve the vision, make the resource deployment decision to achieve the selected strategies, and build alignment to the vision and strategic direction, throughout all levels of the organisation." He further asserts that strategic planning brings to life the mission and vision of the enterprise. Comprehensively, strategic planning would emanate from a clear exposition of a school's vision and mission, anchored in the goals it wishes to achieve socially and economically within the values and philosophy of top management. This also involves being cognisant of the market forces, product, service and learners being catered for (Wall, 2016). Contextually, top management and teachers in strategic planning conceive the guiding principles of a school as they seek to define its purpose to justify its existence in the turbulent competitive global environment for the benefit of its learners. For instance, as highlighted above, if one of the school's priorities is to achieve academic excellence, top management and teachers must jointly identify skills and resources needed to achieve such a priority. A lack of skills will demand that teachers, as implementers, be re-oriented through staff development programmes in the appropriate pedagogy needed. At the worst, top management may request such skilled personnel through the regional staffing officers to augment the school's aging staff complement as a long-term replacement strategy. In addition, mass resource mobilisation in partnership with the community in which the school is located will equally be needed if learners are to receive the much-desired quality education.

Furthermore, top management's philosophy, founded on consent and consensus, is packaged in the vision, mission statement, values and goals that harmonise the school activities and its strategic plan for monitoring and evaluation purposes (Wall, 2016). It is noteworthy that a strategic plan must operate in an extended timeframe in an attempt to translate its vision and values into significant, measurable and practical outcomes (Wall, 2016). These movers of the school end up being the key performance indicators (KPIs) that are used to measure the institution (OnStrategy, 2021). Above all, successful strategic planning process demands wider consultation to enhance commitment and ownership, information gathering of the current position of the school and the generation of options in a creative way grounded on data gathered within its cultural context and the comfort levels of participants as the way forward is sought (Kukreja, 2013).

The hierarchy of organisational plans

Traditionally, the crafting and execution of strategic plans have been hierarchical (Kukreja, 2013). This orientation gave birth to three hierarchical plans, namely operational, tactical and strategic (Stoner et al., 2008). Strategic plans are the broad goals of the organisation and are designed by top management (education manager/ deputy/senior staff/governing body). These plans deal with relationships between people at the school and those acting at other schools. At a tactical level is middle management of the school system (deputy education manager/senior staff/ heads of department) whose task it is to identify specific objectives based on specific activities. Then, at an operational level, all staff members would devise minute details of regularly executing those strategic plans (Wall, 2016). Finally, top management would scrutinise the plans for approval and alignment to the vision and mission statement of the school for monitoring and evaluation purposes (Albon et al., 2016). Such plans are differentiated by their time horizon, the scope and the degree of detail (Stoner et al., 2008).

The strategic planning process in the school

Top management formulate the vision and mission statement of the school. The vision should reflect the management's aspirations for the school and its business. It should provide a panoramic view of its roadmap and destination and give specifics about its future endeavours in a competitive global village (Rutherford, 2015). O'Reilly and Tushman (2004, in Maleka, 2015:26) view its compelling vision as its driving force, which is "relentlessly communicated by an organisation's senior team, as crucial for building organisations that can respond to rapid changes in technology and markets." Through market research the learners' need deficiencies should be identified so that child-centred methods can be designed in order to develop their potential to the fullest (Kukreja, 2013). Central to the vision and mission statement are the needs of learners, which must be quantified and incorporated as they constitute the KPIs of the school (OnStrategy, 2021). Top management, armed with the vision and mission statement, would attempt to generate a strategic plan by scanning the internal and external environment using the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats (SWOT) matrix management tool (OnStrategy, 2021). This would entail identifying the critical success factors in the form of outcomes that are prerequisites in the school system and would determine the extent to which the vision and mission, values and learners' needs/wants are being met (Wall, 2016). Middle management would also use the SWOT matrix to identify specific objectives of the school curriculum based on specific activities at a tactical level (Stoner et al., 2008).

In similar fashion, staff members would endeavour to translate the strategic goals and tactical objectives into an operational strategy. This would compel them to generate departmental vision and mission statements in sync with that of the school (Fernandes, 2018). Ultimately, such plans would need top management's approval for the purpose of allocating resources, monitoring and evaluation (Wall, 2016). The latter exercise provides top management with the consent and consensus of all stakeholders to modify, institutionalise or terminate the strategic plan based on empirical evidence (Rutherford, 2015). Related studies conducted in industries reveal that involving super-ordinates and their subordinates in crafting strategic plans make them productive, effective ambassadors of the organisation in the larger community with engagement levels of 60% (Fernandes, 2018).

However, if schools are to be effective, professional hierarchies should not be rigid structures as status symbols, but flexible to enable staffers to relate to one another regardless of their position (Wall, 2016). This would allow unhindered professional inputs and direct or indirect participation from all stakeholders (Kukreja, 2013). To achieve this, top management would need to appoint strategic directors to champion the action of translating their set goals into operational objectives for implementation and evaluation (Kukreja, 2013). In all these instances, the vision, mission, values and goals become a standard bearer from which KPIs are derived for quality assurance and control purposes (OnStrategy, 2021).

Theoretical Framework

Take Stock Analysis (TSA) model

Among the several models suggested by strategists, the TSA model (Fidler, Edwards, Evans, Mann & Thomas, 1996), which appears to be an embellishment of the basic, issue-based and SWOT analysis theoretical framework (Asana, 2023), has been singled out for this study as it is user-friendly. In their endeavour to transform their school environments through strategic planning, top management and teachers must know that radicalism is counterproductive as it triggers great challenges. When in such a quagmire, they should not hesitate to engage consultants as strategic planning is a new phenomenon in schools. Whatever changes are introduced within this context must be based on logical step-by-step actions as opposed to radical changes (Fidler et al., 1996). The key features of the TSA model are the following:

• The past and present situation. (This is essential and meant to review the historical past of the school and map the way forward.)

• The mission.

• Opportunities and threats.

• Strengths and weaknesses.

• Critical issues of the future (Fidler et al., 1996).

SWOT analysis

According to Maleka (2015), this is a commonplace strategic planning tool that top management and teachers may use in determining an institution's potentials. It entails two elements -an internal analysis concentrating on the performance of the institution vis-à-vis its external performance. To do this the SWOT analysis must be used in conjunction with the PESTLE (political, economic, social, technological, legal, environmental) analysis tool (Asana, 2023). Schools may use these management tools in conjunction with the TSA model. For instance, in the first phase, top management, in consultation with the staff, learners, governing body and the community may use these tools by way of strategic analysis to determine the current position of the school as they attempt to map its way forward (Martins, 2024). The process entails determining the factors that would influence the school in the short and medium term and those that affect the choice of strategy. Furthermore, it is crucial for top management to establish the boundaries of the school so that they will be able to scan its internal and external environment using the SWOT/PESTLE analysis tools, if they are to appreciate its interface with its environment (OnStrategy, 2021). Such a strategic analysis of the ecological, legal, political, economic, social and technological trends of the school environment results in an informed strategic choice (OnStrategy, 2021). In the process consideration should be given to competition, demographic variables and the scope of coverage that must be contextualised to establish opportunities and threats to the school (Sallis, 2005).

Similarly, if the school's strengths and weaknesses are to be established and articulated at a performance level an internal audit is needed. This would entail examining the following: learners' needs, curriculum, funding, staffing, enrolment, non-curricular activities, pedagogy, public examination success, availability of resources, managerial structures, marketing and the monitoring and evaluation component (Fidler et al., 1996).

After completing the strategic analysis of the internal and external environment using the appropriate management tools, key areas emerge under the headings: strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. This exercise is meant to enable top management and teachers to maximise strengths that may be used to market the school, minimise weaknesses, reduce threats that may hinder the execution of the strategy and build on opportunities which may be used to ensure the success of the plan (Rutherford, 2015). The process is strengthened by concentrating on the learner's needs and the school's competitive context as the strategic choice is made (Hinton, 2012). Most important is the sense that the process aids the generation of the school's vision, which is translated into a mission statement that informs the strategic implementation process through its values and goals (Hinton, 2012). This is what makes a school's strategic plan unique and different from that of its rivals, thus making it attractive to its clientele (Sallis, 2005). In all these processes, top management should seek to reach consensus on the common goals of the school to evoke meaning appropriate to the institutional players (Wall, 2016). Furthermore, the strategists must be prepared to take high risks in return for high rewards when choosing the best option for strategic implementation during the school development planning process while keeping within its budgetary constraints (Rutherford, 2015). The resultant strategic plan must be subjected to scrutiny for the purposes of modifying it (Wall, 2016). The use of the TSA model together with the appropriate management tools of analysis, if meticulously done, must generate ideas for the vision, mission, values and the goals of the school's strategic plan (Fidler et al., 1996).

Vision

Sallis (2005:119) claims that the vision of the school "communicates the ultimate purpose of the institution and what it stands for." When properly formulated, it gives direction to the school as it navigates its turbulent internal and external environment (Fernandes, 2018). In addition, it must be holistic, unique, culturally bound, appealing and must bond the relationship of the school and its broader community (TowerStone Leadership Centre, 2016). To make it easy to remember, it must be presented in bullet form (Sallis, 2005).

Mission

The aim of the mission statement is an attempt to translate the vision statement into an operational manual which everybody else must be acquainted with (Ward, 2018). It articulates the purpose of the organisation, its existence in the present and future (Ward, 2018). It also clarifies why the school is different from others and is backed up by well-formulated long-term goal-related quality strategies (Hinton, 2012). In collaboration, Hinton asserts that it is a concise statement of purpose that spells out how the school's intentions are going to be achieved through its operations. In adverse competition, this is what makes schools unique and enables parents to make strategic choices. Above all, a good mission statement must be learner oriented for it to attract gifted learners, compact, memorable, meaningful, focused, easy to communicate, quality and commitment conscious, aimed at the long term, and flexible (Sallis, 2005). When one analyses it, it must yield the vision and core values of the future (Fidler et al., 1996).

Values

Based on one's deeply held beliefs that direct decision-making, one's behaviour is driven by unseen drivers (TowerStone Leadership Centre, 2016). Values are building blocks upon which the school's principles, beliefs and aspirations are built to achieve its vision and mission (Sallis, 2005). This collective behaviour by all stakeholders becomes the cultural baggage on how things are done in any given school (TowerStone Leadership Centre, 2016). For teachers to be the school's brand ambassadors, their personal values must be congruent with those of the school (Rutherford, 2015). Such a thrust would lead to high levels of performance and pursuit of excellence for the benefit of the learners and the school (TowerStone Leadership Centre, 2016). Furthermore, values must be few, crisp and drive the school in the appropriate direction (Sallis, 2005). Above all, they should be communicable throughout the institution in a consistent manner. In that way, they will be able to strike a chord with both learners and teachers (Sallis, 2005). All that top management and teachers need to do is to inspire their learners by modelling the appropriate value at any given time to allow everyone else to fit in with the culture of the school. Such a culture would require a shared vision if the school was to have a competitive advantage over its rivals (TowerStone Leadership Centre, 2016).

Goals

Finally, the vision, mission and values must be translated into achievable goals (Hinton, 2012). These may be expressed as aims and objectives with the latter being expressed in measurable terms to accommodate evaluation (Ngwenya, 2011). Furthermore, goals are the compass of a school's activities. They focus on efforts of individuals, coordinate their activities and guide strategic plans and decisions (Hinton, 2012).

All the above processes should take place against the background of market research which should be continuous due to the complexity of the human element if their needs and wants are to be approximated (Sallis, 2005). Learners do not have repeat possibilities but are replaced by new cohorts (Sallis, 2005); hence a guinea pig approach would be disastrous. Market analysis must consider the segmentation of the markets since each segment requires different needs and perceptions, hence the need to continuously engage in such activities if strategic plans are to remain relevant and realistic to the institutions they serve (Sallis, 2005). Ideally, at operational level, each department must have its strategic plan aligned to that of the school (Wall, 2016).

Methodology

The ontological and epistemological philosophical assumption that informed the qualitative methodology adopted for this study was constructivism/interpretivism as I sought to answer the question: How are top management and teachers involved in the strategic planning process in Zimbabwean schools? The paradigm was premised on the belief that no real world exists as reality is socially constructed from the individuals' multiple experiences from which subjective meanings are developed as they seek to understand the world they work and live in (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015).

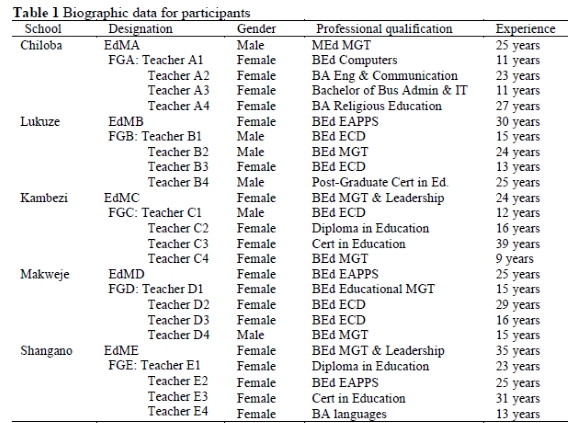

Since the study adopted a relativist view of the social world, a case study utilising inductive, naturalistic and subjective methods was used to investigate the strategic planning process in Zimbabwean schools as depth, not breadth, was sought (Yin, 2012). The multiple versions of how top management and teachers devise strategic plans in different schools were used to develop knowledge about the phenomenon grounded in the data gathered (Charmaz, 2014). For that reason, a small sample of participants comprising five education managers and 20 teachers was purposefully selected from the five district schools located in the Bulawayo Metropolitan Province based on their professional qualifications and teaching experience (cf. Table 1). The selection criteria used enhanced the credibility of the responses (Creswell, 2018).

Data were gathered from five education managers who were the key informants in this study, using a face-to-face semi-structured interview protocol comprising four open-ended questions, which were a breakdown of the main research question. In similar fashion, opinions were solicited from the teachers in their constituted focus groups compatible with a constructivist paradigm that values multiple realities from participants (Yin, 2018). When responding to interview questions, the participants were observed as well. To supplement the interview data, document analysis was also employed. Each school supplied me with its own strategic plan, which was analysed against that of the MoPSE and the literature reviewed directed by the following statements: when it was formulated and by whom, its vision, mission statement, values, goals, review dates and how supervisors monitor and measure the school's activities based on the strategic plan. In that way, data gathered from different sources were triangulated for authenticity, dependability and conformability (Yin, 2018). Theoretical saturation determined the sample size of the strategic plans and participants (O'Leary, 2014). Non-participating schools and participants within the district were used to pilot test the instruments. The biographic data of the participants are shown in Table 1 below.

Education Managers

Table 1 reveals that all the female education managers (EdMs) interviewed were holders of a first degree in Education MGT while EdMA, a male participant, had a master's degree in the same discipline. It further shows that EdMC was the least experienced (24 years) while EdME had served the longest (35 years).

Teachers

Similarly, of the 20 teachers who participated in this study in their respective focus groups (FGs), all were female, except five. In both cases, the sample was skewed towards female participants because of the Zimbabwean deployment and appointment of female teachers and EdMs respectively, in line with the Ministry's gender policy in urban schools. All held degrees in different disciplines, except five who were either holders of a certificate or diploma in Education. Despite not holding degrees, the latter group of participants could not be ignored in this study because of their teaching experience, which ranged between 9 and 39 years. However, Kambezi School had the least and most experienced teachers who had taught for 9 and 39 years respectively.

Data Analysis

The interactive process used to analyse the qualitative data captured was a combination of thematic analysis for the interview data and content analysis for the document data using the Tesch method (Bowen, 2009). Interview data were first transcribed. Similar and dissimilar ideas were clustered separately and later on examined for differences. These ideas were then coded and segmented into major categories and subcategories. Emergent data were used to fine-tune and merge the categories based on their relationships. Categorisation and abstractions reduced the segmented data into themes upon which theory was developed. Document data derived from the analysis of strategic plans based on the preconceived notions set supplemented interview data (Yin, 2018). The resultant collated data were reported using thick descriptions, which enabled me to particularise the theory developed to a given context as opposed to generalisations (Korstjens & Moser, 2018).

Complying with research ethics, permission was sought from the Provincial Education Director of the Bulawayo Metropolitan Province, the University of South Africa Ethics Review Committee (Ref#:2019_CRERC_005 [FA]) and EdMs of schools. Informed consent was also sought from the participants and those who freely volunteered signed the consent forms. Schools and participants in this study are identified by pseudonyms conforming to the ethical requirements of privacy, anonymity and confidentiality (Best & Khan, 2014; Yazan, 2015).

Findings

The data analysis process yielded three thematic areas, namely the concept of strategic planning, the formulation process and the monitoring and evaluation of the implementation process.

The Concept of Strategic Planning

When the participants' conceptual understanding of the strategic planning process was sought as it pertains to schools, their responses were varied although unanimous. EdMA, EdMB and EdMC viewed it as "conceiving a short-and long-term plan which entails the mobilisation of resources aimed at achieving specific goals for the purposes of developing the school'" EdMD further opined that it involved "strategising priorities" while EdME reported that "it spelt out the futuristic direction of the school within its budgetary means in an attempt to operationalise the strategy. " The futuristic-mapping as expressed by EdMs of schools is in keeping with Fidler et al.'s (1996) TSA model of strategic planning.

Concurring with the above perceptions were teachers in their various FGs. FGA defined it as "an outline of broad goals and objectives meant to achieve educational goals" while FGB and FGE viewed it as "a short-and long-term plan involving the mobilisation of resources in an attempt to move the school from its status quo to its desired state. " Corroborating the views of EdMA, EdMB and EdMC, FGD perceived it as "steps followed by a school in determining the vision, mission and goals of the school." Little wonder that FGC referred to it as "a written plan of the school's educational philosophy, its aims and how it proposes to achieve them." In that light, the researcher concluded that the participants' perceptions resonated with those reviewed.

Formulation Process

All participants were questioned on how their current strategic plans were crafted. Their collective opinions are summarised below.

Needs analysis and identification All participants opined that a situational analysis of the external and internal environments in which they operated was analysed as confirmed by EdMC by saying, "we utilised a SWOT analysis tool to identify our operational needs", echoing Fidler et al. 's (1996) model. Two versions emerged from their multiple responses, depending on whether the process was centralised or decentralised. In the former, top MGT were utilised as reported by FGE in "the needs analysis is done by the regional office, the education manager and the governing body. They are the ones who set the strategic goals according to their priority list and teachers are followers", while in the latter, a departmental approach was employed as demonstrated by FGA in: "School's strategic goals are given to departments. Departments conduct their needs analysis at departmental level and make their situational strategic plans which must be aligned to the school's strategic goals. Top MGT will scrutinise such plans for compliance." However, departing from the norm was Shangano School where a consultant was employed for this purpose: "Top management hired a consultant who facilitated the needs analysis and the writing of our strategic plan." Thereafter, their identified needs were communicated to all stakeholders as soon as they were scrutinised and approved by top MGT.

Target setting and prioritisation of needs

Both EdMs and teachers interviewed seemed to indicate that the jointly identified needs were then translated into objectives or goals, which were supposed to be completed within a specified time depending on the magnitude of the task as collectively expressed by EdMA, EdMC and EdME: "At our schools, mainstreaming of the ECD department to the regular primary school demands that we mobilise the community to generate funds for the construction of an ECD block to decongest the school." This view was corroborated by FGB, FGD and FGE who appeared to be adversely affected by the same predicament: "The completion of whatever project according to the SDP priority list is determined by its size and the socio-economic background of the community. Some projects are short-term while others are long-term." The chosen project becomes KPIs which every school looked forward to accomplishing as postulated by Kukreja (2013) and OnStrategy (2021). It is at this stage that the KPIs set were either prioritised by top MGT alone or in consultation with the teachers or parent assembly depending on the modus operandi used by a specific school.

Budgeting

Both EdMs and teachers agreed that an inclusive approach was adopted in identifying the sources of funding and resources needed to accomplish the prioritised KPIs. EdMA went further to aver that whatever resources were available they were allocated to both major and minor projects, which in his school were implemented concurrently: "Top management and teachers met to identify sources of funding and mobilise resources for the prioritised projects." This opinion was also emphasised by FGA who intimated that "[b]udgeting is not a one-man band. All stakeholders must come on board, brainstorm together and put on paper what has been agreed upon."

Formulation of the strategic plan

It appears the participants' route was determined by the approach adopted. In a centralised approach, the plan was crafted by top MGT in consultation with various stakeholders whereas in a decentralised one, consultants spearheaded the process as indicated by EdME: "The education manager, deputy head, heads of departments and the parent body come up with a strategic plan, which is later on marketed to all stakeholders so that they would buy into it." This view was reiterated by FGE who said: "Heads of departments guided by the Ministry's strategic plan were assembled to spearhead the formulation of the strategic plan working together with top management. After that, the final product was tabled to the teachers for ratification." EdMB and FGB further argued that the process was made easier by the availability of the MoPSE's strategic plan which served as the model for most schools. On completion, it was submitted to top MGT for approval. In both cases, whatever strategic plan was adopted by the school, either top MGT or an appointed strategic director or the consultant presented the plan to the various stakeholders. The final product constituted the SDP as FGD pointed out: "The prioritised goals constituted the SDP." Thereafter, tasks and resources were allocated to teachers or departments for implementation.

Monitoring and evaluating the school activities against the strategic plan

Both EdMs and teachers reported that monitoring and evaluating the plan were done by the district inspectors, top MGT, consultants, staff, and parents. They also opined that depending on the magnitude of the project, formative evaluation was either done monthly, termly or yearly as EDMA remarked: "development programmes are periodically evaluated to see whether they are a success or not." The process seemed to be characterised by review reports, which assisted schools to either modify or adjust the targets initially set (Fernandes, 2018) as expressed by FGB: "The school has a document that helps to track and assess the results as an intervention throughout the life of a programme. The strategic plan is regularly referred to and updated on a regular basis." In concurrence, FGC remarked that the monitoring and measuring of the school activities against the strategic plan "is done jointly by all stakeholders as it helps to keep the school on track, making adjustments here and there to keep you driving towards the vision". However, EdMC refuted this latter claim as theirs was last reviewed 3 years ago. Based on these tone contradictions I surmised that the teachers of Kambezi School might have twisted the truth. This observation was buttressed by the evidence derived from the analysis of the SDPs which revealed that none of the aspects of the new curriculum were incorporated at all. Further evidence was revealed by FGD who remarked that "district school inspectors never ask for the SDP when inspecting schools or teachers." Noteworthy though, where failure was registered, they all went back to the drawing board.

Document analysis

Five of the EdMs of the schools investigated provided their strategic plans for scrutiny. These plans were analysed against that of the MoPSE in respect of the vision, mission, values and goals as it served as a model for most schools and the results are reported below.

The vision statement of the MoPSE was made up of 18 words (To be the lead provider and facilitator of 21st century inclusive quality education for socio-economic transformation by 2020) while that of Chiloba School had 11 words (To be the lead provider and facilitator of inclusive quality education). The vision statements of Kambezi and Makweje were 14 words each; and that of Lukuze and Shangano 17 and 20 words respectively. To test whether FGA of Chiloba School knew their vision statement by heart, when they were asked to recite it. None recited it verbatim; save for bits and pieces. This discovery raised questions, especially since it was the shortest.

Similarly, the analysis of the mission statement revealed that the shortest was that of Makweje School with 14 words and the longest was that of Kambezi School which had 35 words (Kambezi School will endeavour to pursue academic excellence that will develop the children physically, emotionally, intellectually, morally as well as socially, so as to enable them to participate meaningfully and actively and within their communities). Those of Lukuze, Shangano and Chiloba Schools had 21, 22 and 29 words respectively against that of the MoPSE which had 10 (To provide equitable, quality, inclusive, relevant Infant and Secondary education).

Furthermore, the strategic plans revealed that the core values of schools investigated ranged from seven to 11 against those of the MoPSE which were seven (commitment, integrity, empathy, teamwork, accountability, transparency and good governance). The fashionable ones that resembled those of the MoPSE were "integrity, teamwork, commitment, transparency and empathy." Some values featured as well depending on the school's unique characteristics such as "diligence, cleanliness, discipline, self-reliance, resourcefulness, humanness and punctuality." In some cases, some schools repeatedly expressed the same value but using a different adjective such as "commitment" which is synonymous to "dedication" and "diligence" to "hardworking."

Noteworthy are the goals set out in the strategic plans that all participants claimed were prioritised and became the operational objectives on which the school was monitored and evaluated. These were factored in the SDP of the strategic plan covering a period of 5 years. Two of these were crafted in 2015, another two in 2016 and the last one in 2018. The goals seemed to differ according to the immediate needs of the school. Because of the mainstreaming of the ECD classes into the regular schools, most schools had either completed the ECD block or were on the verge of doing so: "To ensure that a classroom block consisting of five classrooms is constructed to cater for ECD classes by 2020." Others were mobilising resources meant to equip the computer laboratory to accommodate the demands of the new curriculum: "To buy at least 10 laptops a year." However, Chiloba School seemed to focus on academic excellence: "To achieve a 100% pass rate in the national examinations in all six subjects", and were equally excelling in sporting disciplines. The latter was evidenced by the multitudes of trophies on display. Interesting to note was that, all the objectives set were given a timeframe to facilitate the monitoring and evaluation process and were expressed in behavioural terms.

Discussion

Top MGT and teachers who participated in this study seemed to have had the capacity to contribute to the strategic planning process judging by their perceptions of the concept, professional qualifications and experience.

Strategic Planning Needs Analysis and Formulation Process

Their involvement in the needs analysis and formulation process was determined by whether a centralised or decentralised approach was followed or whether a consultant was engaged. In all instances, top MGT and teachers were actively involved in conducting the situational analysis of the internal and external environment using the SWOT/PESTLE analysis tools of MGT as postulated by Rutherford (2015) and affirmed by EdMC. However, in a centralised approach, the identified needs were later shared with the teachers for consensus building (Wall, 2016) whereas those generated from the grassroots were submitted to top MGT for fine-tuning and approval. Top MGT bore this responsibility because they are in a strategic position of the institution. They allocate resources, monitor and evaluate the implementation process and are held accountable to whatever happens in schools (Wall, 2016). Effective communication was also used where either approach had been used. However, the engagement of consultants demanded vigorous and aggressive marketing of identified needs to various stakeholders to avoid rejection (Rutherford, 2015).

Target Setting, Prioritisation of Needs and Budgeting

Both parties were involved in setting targets and producing a priority list based on their strategic choices of the needs identified to enhance their commitment and ownership of the process. However, instances where top MGT set targets separately and communicated them to the teachers and other stakeholders later on for ownership and shared governance were also observed. It is noteworthy that the inclusive approach was also used in the budgeting process, which enabled both parties to mobilise adequate resources for the implementation and accomplishment of KPIs.

Centralised or Decentralised Strategic Planning Formulation Process

However, when it came to the actual crafting of the strategic plan, two versions emerged. Either a centralised approach involving top MGT or a decentralised one involving teachers in their different departments of specialisation was used. In some schools, consultants were hired to spearhead the process either in a centralised or decentralised model (Martins, 2024). In the latter, approval was still sought from top MGT as alluded to above. Key to the crafting process was the MoPSE's strategic plan which appears to have served as a model for most strategic plans. After that, it became the responsibility of the crafting party to market the plan to other stakeholders for acceptance.

Strategic Goals

Interesting though, was how the goals of the strategic plans were varied and unique in an attempt to harmonise the vision, mission statement and values of the school (Sallis, 2005). These goals galvanised the implementation process and were used by various stakeholders to monitor and evaluate the SDP and KPIs. Evidence of participants having a shared vision in pursuit of goals which drove their strategic plans and decision-making process was exhibited in various projects undertaken or achievements made. However, records of projects undertaken lacked feedback comments.

Vision Statement

Disappointing though was the failure of participating teachers to recite the shortest vision statement despite the knowledge that they had possessed on the phenomenon and their involvement in the strategic planning process, as claimed. I doubted whether learners and parents knew it, and deduced that most schools had an illiterate parent population. This was a cause for concern as vision statements are radars that must drive the school into locomotion, let alone strategic plans (Sallis, 2005). As a result, I surmised that Chiloba School was probably a typical example of those schools whose strategic plans were crafted by consultants to fulfil a bureaucratic requirement and left to languish on the shelf (OnStrategy, 2021). In similar fashion, Kambezi School's mission statement, which was the longest in the literature reviewed, was questioned as well.

Strategic Values

Confusing though, were values that lacked clarity as some of them were expressed in professional jargon and in other cases were either many or a duplication of synonyms. Values were considered crucial in this study as they reflect the philosophy upon which the vision and mission statements are built based on the school's cultural beliefs (TowerStone Leadership Centre, 2016). In this regard, top MGT and teachers are expected to model such behaviour to their learners so that, in turn, learners become their brand ambassadors in the communities they serve.

Evaluation of SDPs

Finally, the analysis of the strategic plans revealed that they were still in their infancy considering the time (2015) when they were crafted and the time (2019) when they were investigated. Despite that, none of the strategic plans or SDPs had been reviewed in line with the sweeping changes brought about by the new curriculum and technological changes occurring in schools (GoZ, 2015). This sentiment concurs with EdME's observation, although contradicted by her teachers.

Conclusion

The empirical evidence of the study reveals that all EdMs investigated were professionally sound and possessed extensive executive powers to spearhead a strategic planning process. Zimbabwean schools have grown in size and macro planning has been decentralised through devolution (Albon et al., 2016; GoZ, 2013). The decentralisation of the strategic planning process seems to have compelled top MGT and teachers to embrace the strategic planning phenomenon in their endeavour to outsmart and outperform one another in their attempt to be unique in an ever-changing competitive and technological environment. Top of the agenda was a collaboration of minds and effective communication displayed at all levels of the strategic planning process regardless of whether the approach adopted was centralised or decentralised. This was meant to enhance commitment and ownership of strategic plans by both parties in an attempt to satisfy learners (Rutherford, 2015). Above all, the study has also revealed that planning and decision-making are at the centre of the strategic planning process.

Although most schools' strategic plans were a product of the philosophy and vision of top MGT (Wall, 2016), the fact that it was founded on the consent and consensus of the teachers, culminated in a home-grown plan being crafted. Such an approach facilitates the collaboration needed between both parties in the translation of the vision into the school's mission statement, values and goals. This kind of engagement is critical because top MGT deploys teachers and allocates resources needed for the successful implementation of the strategic plan based on the SDP priority list while teachers provide the deliverables based on the needs of the learners. The harmonisation of the formulation process and implementation of the strategic plan enables both parties to jointly monitor and evaluate it according to a targeted timeline. Such engagement makes the strategic plan to be perceived as a blueprint to anchor the vision, mission statement, values and goals of the school.

However, a disturbing revelation in the study is where strategic plans are crafted by hired specialists or top MGT assisted by consultants to fulfil a bureaucratic requirement. Consequently, such strategic plans, although cosmetically marketed to various stakeholders for acceptance and action, end up gathering dust on the shelves as they are foreign to would-be implementers and beneficiaries (Hinton, 2012). As a result, the strategic planning process and the end-product itself become a waste of resources.

Recommendations

Based on the findings of the study, some Zimbabwean schools are commended for using the democratic space created by the decentralisation and devolution of the strategic planning process to school level, but others were found wanting. In that regard, I recommend that the entire strategic planning process should not be left to top MGT only. All stakeholders should be actively involved, including learners at secondary level. This is necessary to familiarise the implementers and would-be beneficiaries with strategic plans. Such a thrust would facilitate the monitoring and evaluation of the strategic plans through the SDP by all stakeholders. However, where expertise is wanting, consultants may be invited to facilitate empowerment workshops. Top MGT and teachers could be trained in the knowledge and skills needed for them to go through the strategic planning process independently, as delineated above. By and by, keen teachers who master the skills needed may be appointed as strategic directors or constitute a strategic planning committee to spearhead future strategic planning processes to wean schools from depending on outsiders. Teachers in any change process usually prefer a bottom-up approach as opposed to a top-down one.

On the contrary, in mandatory instances where top MGT or the EdMs, in particular, are supposed to come up with a vision statement that serves as a compass to their schools, it would be advisable to have a strategic planning committee to fine-tune the vision statement in sync with the realities on the ground after affording all stakeholders an opportunity to make inputs (Hinton, 2012).

Furthermore, it is recommended that if strategic plans are to remain relevant in schools, they must be modified periodically as part of the SDP. This can be done by way of formative evaluation and subjected to a summative evaluation at the end of every timeline. The former is a quality assurance intervention strategy while the latter exposes the threats experienced, which can then be turned into opportunities in future endeavours.

Finally, top MGT and teachers must be equipped with the technical knowhow of using the SWOT/PESTLE management tools to analyse any given environment they find themselves in through a brainstorming session if shared goals were to be realised in keeping with the theoretical framework which informed the study. This analytical tool will enable them to have a broader picture of the turbulent environment they are confronted with as they craft a competitive strategic plan that will enable them to outperform their competitors.

Acknowledgements

My special thanks goes to the Provincial Education Director of the Bulawayo Metropolitan Province who granted permission for schools within her jurisdiction to be investigated, the University of South Africa Ethics Review Committee, education managers of the five districts of the sampled schools and the professional editor.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Albon SP, Iqbal I & Pearson ML 2016. Strategic planning in an educational development centre: Motivation, management, and messiness. Collected Essays on Learning and Teaching, 9:207-226. Available at https://celt.uwindsor.ca/index.php/CELT/article/view/4427. Accessed 31 December 2023. [ Links ]

Asana 2023. Seven strategic planning models, plus eight frameworks to help you get started. Available at https://asana.com/resources/strategic-planning-models. Accessed 31 December 2023. [ Links ]

Best JW & Khan JV 2014. Research in education (11th ed). London, England: Alyn and Beacon. [ Links ]

Bowen GA 2009. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2):27-40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027 [ Links ]

Charmaz K 2014. Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2018. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed). London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Fernandes P 2018. What is a vision statement? Available at https://www.businessnewsdaily.com/3882-vision-statement.html. Accessed 7 May 2020. [ Links ]

Fidler B, Edwards M, Evans B, Mann P & Thomas P 1996. Strategic planning for school improvement. London, England: Pitman. [ Links ]

Government of Zimbabwe 2013. Constitution of Zimbabwe. Harare, Zimbabwe: Author. Available at https://www.dpcorp.co.zw/assets/constitution-of-zimbabwe.pdf. Accessed 31 December 2023. [ Links ]

Government of Zimbabwe 2015. Curriculum framework for primary and secondary education. Harare, Zimbabwe: Author. [ Links ]

Hinton KE 2012. A practical guide to strategic planning in higher education. Ann Arbor, MI: Society for College and University Planning. Available at https://www.vincentgaspersz.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Higher-Education-Strategic-Planning-Guide-VG.pdf. Accessed 31 December 2023. [ Links ]

Korstjens I & Moser A 2018. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. European Journal of General Practice, 24(1):120-124. https://doi.org/1080/13814788.2017.1375012 [ Links ]

Kukreja D 2013. Strategic planning: A roadmap to success. Ivey Business Journal. Available at https://iveybusinessjournal.com/publication/strategic-planning-a. Accessed 1 August 2018. [ Links ]

Maleka S 2014. Strategic management and strategic planning process: South African perspective. Paper presented at the DTPS Strategic Planning & Monitoring workshop, Pretoria, South Africa, 14 March. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273757341_Strategic_Management_and_Strategic_Planning_Process. Accessed 31 December 2023. [ Links ]

Martins J 2024. What is strategic planning? A 5-step guide. Available at https://asana.com/resources/strategic-planning. Accessed 23 January 2024. [ Links ]

Merriam SB & Tisdell EJ 2015. Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Ngwenya VC 2011. Performance appraisal as a model of staff supervision in Zimbabwe: The case in Zimbabwean schools with specific reference to Makokoba circuit. Saarbrücken, Germany: LAP Lambert Academic Publishing. [ Links ]

O'Leary Z 2014. The essential guide to doing your research project (2nd ed). London, England: Sage. OnStrategy 2021. Strategic implementation. Available at https://onstrategyhq.com/resources/strategic-implementation/. Accessed 21 April 2021. [ Links ]

Rutherford C 2015. Planning to change: Strategic planning and comprehensive school reform. Educational Planning, 18(1):1-10. Available at https://isep.info/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/18-1_1PlanningtoChange.pdf. Accessed 31 December 2023. [ Links ]

Sallis E 2005. Total quality management in education (3rd ed). London, England: Taylor and Francis e-Library. Available at https://herearmenia.files.wordpress.com/2011/09/ebooksclub-org_total_quality_management_in_education.pdf. Accessed 31 December 2023. [ Links ]

Stoner JA, Freeman RE & Gilbert DR, Jr 2008. Management. Englewood Cliff, NJ: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

TowerStone Leadership Centre 2016. What are organisational values and why are they important? Available at https://www.towerstone-global.com/what-are-organisational-values-and-why-are-they-important/. Accessed 1 May 2016. [ Links ]

Wall C 2016. The evolution of strategy, blog post, 9 August. Available at https://www.strategyblocks.com/blog/the-evolution-of-strategy/. Accessed 9 August 2016. [ Links ]

Ward S 2018. How to write a mission statement. Available at https://www.thebalancemoney.com/how-to-write-a-mission-statement-294800. Accessed 2 January 2020. [ Links ]

Xaba M 2006. The difficulties of school development planning. South African Journal of Education, 26(1):15-26. Available at https://www.sajournalofeducation.co.za/index.php/saje/article/view/72/62. Accessed 31 December 2023. [ Links ]

Yazan B 2015. Three approaches to case study methods in education: Yin, Mirriam, and Stake. The Qualitative Report, 20(2):134-152. Available at http://edcipr.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Three-Approaches-to-Case-Study-Methods-in-Education_Yin-Merriam.pdf. Accessed 31 December 2023. [ Links ]

Yin RK 2012. Applications of case study research (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Yin RK 2018. Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Received: 8 July 2021

Revised: 11 March 2023

Accepted: 6 November 2023

Published: 23 January 2024