Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.43 suppl.1 Pretoria Dec. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v43ns1a2379

CALL FOR PAPERS

Inclusion of young children with autism spectrum disorder during the COVID-19 lockdowns

Jabulile Mzimela

Department of Early Childhood Education, School of Education, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa. mzimelaj@ukzn.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Children with autism spectrum disorder face numerous challenges throughout their childhood and beyond. These challenges include demonstrating behavioural and emotional immaturity, and a lack of grasping intuitively unspoken rules and norms, to mention but a few. Deviating from the norm heightens these challenges. One of the sudden changes brought about by the national lockdown was the extended closure of early childhood development centres. There is a dearth of studies that explored the perceptions of early childhood care and education educators' knowledge of the inclusion of children with autism spectrum disorder. As a result, I employed case study methodology to explore these educators' perceptions of the inclusion of young children with autism spectrum disorder in regular education, as well as how these perceptions influenced the inclusion of these children in regular education during the lockdowns of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) period. Three early childhood care and education educators from a semi-urban early childhood development centre were purposively sampled. Using the 4 key principles of special education needs and disabilities, I concluded that early childhood care and education educators lacked knowledge of teaching and accommodating young children with autism spectrum disorder in everyday education during the COVID-19 lockdowns. The study calls for a stern consideration of these educators' knowledge development and reimagination of their understanding of children with autism spectrum disorder during trying times and beyond.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder; COVID-19; early childhood care and education educators; early childhood development centre; inclusivity; lockdown; special education needs and disabilities

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a widespread developmental disease characterised by communication problems, impaired social interaction, and restricted or repetitive behaviour and interests (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). As a result, children with ASD encounter several challenges throughout their childhood years and beyond. These challenges include difficulties in communication, interaction and imagination, behavioural and emotional maturity, as well as interpreting and navigating the social world around them (Mesa & Hamilton, 2022). Hence, these challenges make learning difficult if the special care required is not understood and given at all times.

The globally rampant COVID-19 that hit South African shores in 2020 is believed to have negatively influenced the development of young children with ASD. South Africa's sudden national lockdown characterised by the extended closure of educational institutions, which included early childhood development (ECD) centres, exacerbated the situation. The aforementioned extended closures also applied to ECD centres and the everyday norm and repetitive behaviour of these young children with ASD were interrupted. These daily norms included meeting their educators and "friends" who are usually invisible to others, strange emotions and unexpected emotional reactions. Since society, in general, fails to understand these unusual behaviours, children with ASD suffer extremely when their demands are not understood. It is crucial to recognise that having autism does not diminish a child's worth or make them any less normal as humans (Mesa & Hamilton, 2022:221).

Although several studies indicate that most educators lack knowledge of teaching children with ASD, White Paper 6 (Department of Education [DoE], 2001) and its advocacy for inclusive education, requires just that (Busby, Ingram, Bowron, Oliver & Lyons, 2012; Clasquin-Johnson & Clasquin-Johnson, 2018). The process of facilitating the learning and teaching of children with ASD attending mainstream ECD centres remains a complex and poorly understood area of education worldwide - especially in times of crisis. Essentially, White Paper 6 expands on ways in which the schooling system can include learners with learning disorders in their day-to-day teaching and learning processes. It highlights, however, that "different learning needs may arise because of negative attitudes to and stereotyping of differences, an inflexible curriculum, and inappropriate and inadequate support services, amongst many" (DoE, 2001:17). Literature reveals that it is crucial for the DoE to play a role in assisting educators to achieve the desired level of understanding (Landsberg, Krüger & Swart, 2016; Majoko, 2019).

Since the announcement of the national hard lockdown on 26 March 2020 by the President of the Republic of South Africa (RSA), Mr Cyril Ramaphosa, several debates took place between the Departments of Education, Social Development, Health and other stakeholders about the education and well-being of children in South Africa. As a result of those numerous talks, South Africa's Ministry of Basic Education proposed the implementation of a contingency plan. The plan was to ensure that no child was left unattended (Macupe, 2020). However, there were no declarations whatsoever on how children with various special needs, including those with ASD, were to be assisted during the undefined lockdown periods. Nevertheless, it is plausible that ECD in South Africa remains the cornerstone that foregrounds sustainable development goal (SDG) Number (No.) 4, which proclaims that it is essential to create inclusive environments that nurture learning for all, regardless of disability status (United Nations, n.d.). This was realised as posing a challenge to the implementation of contingency strategies to give a full effect of inclusive education and its pronouncements around prioritising the needs of children with ASD and the pervasive threats arising from their exclusion.

Relatedly, Mazibuko, Shilubane and Manganye (2020) attest that children with ASD experience higher levels of rejection and lower levels of acceptance by their educators who often fail to manage their unique needs. In agreement, Clasquin-Johnson and Clasquin-Johnson (2018) reveal that educators, especially in developing countries like South Africa, are inadequately prepared to teach children with ASD. Thus, this epoch calls for adequately trained early childhood care and education (ECCE) educators. Generally, ECCE educators' magnitude of competence and abilities to teach children with ASD is essential. According to Clasquin-Johnson and Clasquin-Johnson (2018), educators of children with special needs must develop motivation to address the challenges and accept their responsibilities for teaching such children. Literature reveals that it is crucial for all ECCE educators to be aware of all children under their care, to understand their differences and to teach them accordingly in line with their differences in learning (Burchinal, 2018; Mazibuko et al., 2020). In order to achieve such, the "quality ECCE sector is heavily dependent on suitably qualified educators who have an in-depth understanding of what they are doing and why they are doing it" (Harrison, 2020:2) in the children's learning environments.

The purpose with this study was to call for a stern consideration of ECCE educators' development of a body of knowledge and reimagination of their understanding of children with ASD that concedes for their accommodation during trying catastrophic times and beyond. Wood, Crane, Happé and Moyse (2022:16) refer to such times as periods of "severe turbulence in education." Thus, I sought to explore ECCE educators' perceptions of accommodating children with ASD in such times and beyond.

The Prevalence of ASD in Early Childhood Development (ECD) Years

Fundamentally, ECD is an umbrella term that applies to the processes by which children from birth to 9 years grow and develop in all domains; that is, physically, mentally, cognitively, linguistically, socially, and otherwise (DoE, 2001; Department of Higher Education and Training [DHET], RSA, 2017). With this study I focused primarily on children from birth to 4 years. For a logical distinction, the Department of Basic Education (DBE, RSA, 2015) terms this stage of growth as ECCE. In relation, Harrison (2020) states that ECCE educators are those persons who are teaching more than five children from birth to the age of 4 years in a formal or informal ECD centre.

The author further alludes that ECCE educators have the responsibility of not only developing the social and cognitive aspects of young children but also their social, linguistic, emotional, and physical aspects. The Policy on Minimum Requirements for Programmes Leading to Qualifications in Higher Education for Early Childhood Development Educators (MRQECDE) emphasises that ECCE educators should foster children's development in areas such as communication, language development and social interaction as these are important in their daily interaction with children (DHET, RSA, 2017). Regrettably, this is not always the case in contexts where children living with ASD are taught. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), ASD is a complex neurobehavioral condition that includes impairments in social interaction and developmental language and communication skills combined with rigid, repetitive behaviours. As a result, these make children with ASD diverse from their counterparts.

According to Pillay, Duncan and De Vries (2021), the point predominance of children diagnosed with ASD in South Africa is estimated to be 1:68. This figure suggests that there could be over 270,000 people with ASD in South Africa, with an estimated 5,000 new cases per year (Statistics South Africa, 2022). Guler, De Vries, Seris, Shabalala and Franz (2018:1005) highlight that "while ASD research has gained momentum on a global scale in recent years, the majority of ASD research is from the United States and other high-income countries." Nevertheless, Guler et al. (2018) conducted a study in South Africa that revealed that the number of children demonstrating autistic behaviour was increasing tremendously and that there were few specialist public schools for children with ASD. Specialists are overburdened and inaccessible to the majority of children who require them, and an estimated 135,000 children with ASD are not receiving the specialised education that they require (Erasmus, Kritzinger & Van der Linde, 2022). However, after more than a decade of research studies conducted on autism in South Africa, Pillay et al. (2021:1076) accentuate the fact that "there is very little information about autism spectrum disorder in South Africa and not much is known about children with autism spectrum disorder and their educational needs."

Children with ASD are less likely to receive the maximum attention and support to achieve their maximum potential during their early years and beyond (Busby et al., 2012; Mahadew, 2021). Consequently, Bipath, Tebekana and Venketsamy (2021) maintain that these children's social progress is unfavourable unless educators can detect them and provide the necessary advice and help in the learning environments as well as throughout the social environments as early as possible. Accordingly, White Paper 6 aimed to celebrate and value difference and diversity in consideration of human rights, social justice, and equity issues, as well as the social model of disability and a socio-political model of education (DoE, 2001; Guler, Stewart, De Vries, Seris, Shabalala & Franz, 2023).

Conceptual Framework

Recognising the SEND principles for the inclusion of children with ASD

My study is grounded on the four key principles of special education needs and disabilities (SEND). These principles are explained by Hornby (2015) as, a) the provision of all children with challenging, engaging and flexible general education curricula; b) embracing diversity and responsiveness to individual strengths and challenges; c) using reflective practices and differentiated instruction; and d) establishing a community based on collaboration among learners, educators, families, other professionals and community agencies. Hornby (2015:234) upholds that "theories of inclusion and inclusive education have important implications for special education policies and practices in both developed and developing countries."

Provision of all children with challenging, engaging, and flexible general education curricula Regardless of the teaching context, whether it is an ECD centre, mainstream or special needs education school, teaching is a highly demanding profession, with multiple educational reforms within the South African context imposing an even higher demand on educators (Morrow, 2007). Several research studies on the implementation of inclusive education policy in South Africa have found that educators report that they experience the implementation of inclusive education practices in their classrooms as stressful. According to Walton and Engelbrecht (2022:2), "the field suggests that the barriers and enablers approach to inclusive education is limiting because it suggests linear progress towards the goal of inclusive education as successive barriers are identified and eliminated." Engelbrecht and Muthukrishna (2019) affirm that there are inconsistent and often contradictory implementations of this policy. Participants in the aforementioned studies unanimously shared a lack of adequate knowledge of how to tackle some disability cases and formal support structures from the DoE for the successful implementation of inclusive education practices as a dilemma. Such challenging experiences are not confined to South Africa only as Lee, Yeung, Tracey and Barker (2015) express that educators in Hong Kong experience the same.

According to Guler et al. (2018), in order to understand learning and development in children, as well as the barriers to learning they may face, it is necessary to understand the dynamic interaction between these contextual factors. Therefore, in attempting to improve the quality of education for all, it is necessary for ECCE teachers to understand that a range of needs exists among children and that these must be addressed in order to provide effective learning for all. The authors further aver that for ECCE educators to understand the needs of children with ASD, there is a need for more training and guidance from the Departments of Education and Social Development. This was suggested to enhance positionality to identify and further assist children with ASD. Since children with ASD show challenges in activities that involve social reciprocity, communication and intense sensory stimulation, Busby et al. (2012) suggest that emphasis should be on achieving their maximum social and cognitive growth. These could be achieved through the use of curricula that focus on how to better suit their needs (Hornby, 2015). The author further elaborates that "inclusion in an unsuitable curriculum for many children directly contributes to the development of emotional or behavioural difficulties, or exacerbates existing problems, which leads them to be disruptive and eventually results in the exclusion of some of them from schools" (p. 244). Sadly, most children with ASD are admitted to mainstream schools where the ordinary curriculum is followed and their special education needs are ultimately neglected.

Embracing diversity and responsiveness to individual strengths and challenges The creation of an ideal learning environment that embraces diversity and responsiveness to the individual child's strengths and challenges has to be created and planned by the ECCE educators concerned (Guler et al., 2023; Salleh, 2019). This is usually based on their knowledge, where reflective techniques allow for the scrutiny and revitalisation of the environment to accommodate the changing needs of the child. A high-quality inclusive learning environment is produced by the educator and extends beyond the physical learning space (Majoko, 2019; Harrison, 2020). Educators' understanding of the significance of an inclusive environment that embraces diversity in learners' mental capacity lies at the centre of every classroom. There is an immense need for conscientious educators to regard democracy and transformation in relation to embracing diversity within the learning environment (Mahadew, 2021).

Undoubtedly, an inclusive learning environment is a product of an adequately trained ECCE educator who possesses specialised knowledge, experience, and a positive attitude towards inclusivity (Mahadew, 2021; Miles & Singal, 2010) and is also accommodative irrespective of differences. For educators to have positive attitudes and effectively respond to the diversity of children, they must have knowledge and experience of inclusive practice. Salleh (2019) proclaims that three components contribute to a positive learning environment in an ECD setting. These are physical, social, and sequential aspects. For an ECCE educator to be successful, there should be a correlation between individual educators' ability to modify and balance these three components. Such a balance should ensure that all children are included, even those on the spectrum and thus embracing their diversity and responsiveness to their strengths and challenges.

The use of reflective practices and differentiated instruction

Educators play a fundamental role in developing children with ASD adaptation skills and alleviation of social challenges (Clasquin-Johnson & Clasquin-Johnson, 2018). In particular, ECCE educators' primary role in their respective playrooms (classrooms) is to ensure that no child is left behind and unattended during this initial critical stage of their lives. Thus, being reflective in their practice, the literature reveals that it will undeniably help ECCE educators in becoming aware of their underlying beliefs and assumptions about creating inclusive learning environments. Their fundamental role is grounded on the actuality that they have to nurture children's psychosocial development as they are obligated to bridge the gap between home and school (Harrison, 2020; RSA, 1996; Salleh, 2019) as well as lay solid foundations of education. Given the novelty of the profession, there are policies in place that regulate the functionality of the ECD sector that are influenced by the philosophies and goals of the curricula, learning programmes and government priorities. In essence, the system upholds that educators have to demonstrate the ability to develop a supportive and empowering environment for the learners and respond to their educational needs (DoE, RSA, 2000). Bipath et al. (2021:4) aver that "the catalysts of the policy implementation, namely intervention by officials from the DBE, have not realised the urgency to train and support teachers effectively in the implementation of policies."

Landsberg et al. (2016) state that it is significant to acknowledge that the concept of inclusivity is broad and has varied meanings in varied contexts. Necessarily, an inclusive learning environment entails equal opportunities and access for all learners, irrespective of their race, skin colour, gender, sexual orientation, trauma, learning styles, or disability (DoE, 2001). Findings from a study conducted by Lynch and Lund (2011) in Malawi reveal that children with special education needs are usually prone to discrimination because of uncooperative societal attitudes that oppose their attendance at regular and inclusive schools. Most ECCE educators are struggling to create inclusive learning environments where reflection on their own practices is at the cornerstone of their teaching. An unsuitable curriculum for many children with autism directly contributes to the problems they encounter and thus their exclusion from education.

According to Salleh (2019), in Malaysia, for example, the placement of children with impairments is at the discretion of the childcare centre administrator. By the same token, in numerous developing countries, ECCE educators' failure of adopting differentiated instructions is a product of inadequate teacher training and their attitude toward inclusivity (Majoko, 2019). As evidently stated in the South African Educators Norms and Standards (DoE, RSA, 2000), standardised educational ethos is communicated on how educators have to behave as professionals and ECCE educators are not an exception. The system maintains that teachers must exhibit the ability to create a supportive and empowering atmosphere for learners while also responding to their educational needs (DoE, RSA, 2000; Morrow, 2007).

Pervasively, young children are vulnerable citizens of any country (Leicht, Heiss & Byun, 2018). Hence, ECCE educators require knowledge and experience in inclusive practice to have positive attitudes and respond effectively to the needs of children with ASD. Such knowledge will assist in developing their capabilities of creating differentiated instructions that accommodate all young children with special education needs in their classrooms. Sternberg and Zhang (2005) maintain that these children learn in different ways as their needs are individualistic, thus they seem to profit most when instruction is differentiated in some manner to accommodate them.

The establishment of a community based on collaboration among learners, educators, families, other professionals and community agencies Over the past 20 years, there has been a significant shift in educational philosophy regarding the education of children with learning difficulties and occasionally disabilities. Several nations, including South Africa, have taken the lead in implementing policies that promote integration and, more recently, the inclusion of these learners in mainstream environments (Mayton, Wheeler, Menendez & Zhang, 2010).

Thus, all children enter school from diverse family backgrounds with the hope to receive formal education irrespective of their different abilities and competencies as accentuated by White Paper 6 (DoE, 2001). Unfortunately, there is a huge disparity between the quality of schooling of children living in diverse communities and cultural backgrounds.

Pillay et al. (2021) attest that this is more evident in instances where children are from disadvantaged backgrounds. In the aforementioned contexts, parents often do not afford to send their children to ECD centres. Sadly, children with disabilities may not be identified early, henceforth, not receive the necessary assistance needed to achieve maximum growth and academic development on time.

Furthermore, undoubtedly children who do not attend any preschool education do not attain adequate levels of school readiness and as a result exhibit severe developmental delay (Mbarathi, Mthembu & Diga, 2016). Learners who come from these underprivileged contexts also possess the possibility of being categorised as having learning disabilities requiring special attention and are at risk of never reaching their full potential throughout their schooling life (Walton & Engelbrecht, 2022). In support of Walton and Engelbrecht's assertions, Guler et al. (2023) testify that most children with ASD live in poverty, are impacted by income inequality and have limited access to the necessary services and support. This means that, in cases where children with conditions such as ASD are not identified in time, such children do not receive any help at home or even later when they go to school and hence end up at risk of not attaining full social and cognitive growth.

Research has shown that more than 40% of South African families are headed by single parents, mostly women, and the number of families who have living but absent fathers is increasing (RSA, 2015). Poverty, together with a national unemployment rate of 33.9% places a tremendous financial burden on many families (Statistics South Africa, 2022). Even when family members are gainfully employed, a history of intergenerational poverty means that in many traditional African families, the income has to be shared among family members, thereby decreasing the amount of disposable income for disability-related services (Statistics South Africa, 2022).

Together, these socioeconomic challenges place a significant burden on families raising children with ASD. It is, therefore, crucial for research efforts to explore the understanding of aspects of ASD - not only with educators but to create awareness in the whole community. In provoking the significance of community, Alwee (2011:1) accentuates that "to have a sense of community means the existence of a sense of connectedness, that is, feeling belonging to a group that shares a common identity, history and destiny."

The establishment of such collaboration can never be overemphasised. Alwee (2011) assures that such collaboration immensely facilitates positive support to children with ASD, hence promoting family resilience and affirming the reparative potential of families raising children with ASD globally. The whole notion of collaboration between the parents, families, educators, and community is an attempt to fulfil the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO's) assertion that "schools should assist learners with special needs to become economically active and provide them with the skills needed in everyday life, offering training in skills which respond to the social and communication demands and expectations of adult life" (1994:10). Sadly, UNESCO's mission still needs more effort from all parties in order to be accomplished.

Methodology

This qualitative exploratory case study was conducted in an ECD centre located in a semi-urban context. Exploratory case studies are especially effective when dealing with a complex phenomenon (Cohen, Manion & Morrison, 2018). Employment of this research methodology enabled me to get a full and holistic picture of the complexity involved, including contextual elements, interrelationships and unique conditions that may not be reflected in larger studies. The centre manager confirmed that it was officially registered through the Department of Social Development more than a decade ago. The centre migrated to the Department of Basic Education on 1 April 2022 according to the directive by the president of the RSA. The centre admits babies from birth to 4 years. At the time of the study, 165 children were under the care of four female ECCE educators including the centre manager.

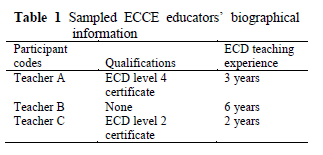

Three ECCE educators (the centre manager excluded) were purposively sampled as participants in this study. Table 1 below gives a thumbnail representation of the participants.

Research Design and Analysis

A qualitative approach was used to elicit credible textual data based on the participants' experiences and actions during COVID-19 hard lockdowns. Data were generated through the use of semi-structured interviews and reflective stories narrated by the participants. The participants had to recall their encounters based on the occurrences between the academic years of 2020 and 2021 and such entries were to be reflected in their reflective journals. Cohen et al. (2018) state that using a reflective journal assists the participant in recalling encounters vividly and voicing their perspective in a non-threatening manner.

Two interview sessions conducted were based on the ECCE educators' availability. The first round of interview sessions lasted approximately 20 minutes. In this session, I explained how reflective journal entries were to be done based on their perceptions. The second round of interview sessions lasted approximately 10 to 15 minutes. I wanted to confirm the participants' responses raised in the initial interviews and the developments in reflective journal entries. All the interviews were conducted after the young children had left the ECD centre. Consent to audio record during both interview sessions was granted by the participants. Cohen et al. (2018) advise that respecting the quality of data is of paramount importance. Based on these assertions, content analysis was adopted.

The authors describe content analysis as "a process by which many words of texts are classified into much fewer categories" (p. 643). In this study, I collated the data from both interview sessions and developed themes that assisted in the classification of data. Consequently, data from the reflective journals were classified and analysed according to responses that displayed connections. Conducting a research ethics approval process can be bureaucratic, time-consuming, and frustrating (Creswell & Creswell, 2017; Petty, Thomson & Stew, 2012).

Nonetheless, I followed appropriate ethical considerations. Firstly, the ethical clearance application to the University of KwaZulu-Natal Research Office to conduct the study was done. The ethical clearance certificate (00017365) was ultimately received. I then requested permission from the sampled ECD centre manager to conduct a research study of such a milieu in her centre. Lastly, I wrote letters of consent to the three sampled ECCE educators requesting them to participate in the research study. Participants were assured that their identities would remain anonymous and that findings would be specifically used only for research purposes.

Findings and Discussion

The reflective journals were the main data generation method. Therefore, data elicited from these reflective journals were systematically organised according to themes for the purposes of clarity and conciseness. Cohen et al. (2018) refer to themes as meaningfully arranged segments of data to find the recurring regularities in them.

Therefore, this allowed me to explore and make sense of data in terms of the participant's definition of the situation and noting patterns, themes, categories and regularities (Petty et al., 2012).

ECCE Educators' Conceptualisation of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Young Children It was of paramount importance to fundamentally understand whether ECCE educators had knowledge of ASD as a neurological and developmental disorder that some children experienced in their lives before embarking on the perceptions that they had about autism. Therefore, the first question was aimed at understanding the participants' conceptualisation of ASD.

Teacher B wrote: "I understand what autism is but sometimes I do not know how to handle a child who demonstrates autism behaviour."

In her journal, Teacher A wrote: "This is frustrating, I do not understand what autism is and it is my first time to work with children who have such unusual behaviours."

Teacher C wrote: "I know what autism is, but no one has ever taught me how to teach a child with autism. "

Reading the participants' journal entries and their responses to the question confirmed Bipath et al. (2021) assertions that educators lacked knowledge of ASD. Although Teacher B had the longest teaching experience at an ECD setting, she lacked specialised pedagogy for teaching children with ASD. Clearly, the concerning issue is that educators have to understand ASD and how children with ASD behave in order to be knowledgeable about how to teach them. Haimour and Obaidat (2013:45) evaluated special education educators' knowledge and implementation of educational practices in Saudi Arabia, and realised that "little attention has been given to examining the qualities of special and general education educators who deliver services to learners in inclusive settings."

This corroborates that in most educational settings, generally, educators lack the knowledge to understand ASD as a pervasive developmental disorder characterised by communication deficits, social interaction impairments and restricted or repetitive behaviours and interests which ultimately result in their frustrations when tasked to teach these children.

In one of the questions, I wanted to know whether the participants knew about different levels of ASD. This question was significant in understanding their knowledge of ASD as a condition that required their specialised knowledge.

Teacher A wrote: "Does autism have levels? I honestly did not know that."

It was not surprising that Teacher B wrote: "I did not know that autism has levels, but I have noticed that some children although I suspect that they are autistic but, on some other days behave pretty well."

Teacher C wrote: "Unfortunately, I don't know anything about levels."

From the journal entries, it was also noticeable that the participants lacked knowledge that ASD had different levels, and knowing these levels would have assisted them in understanding child-specific needs and interventions. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) states that ASD generally ranges from Levels 1 to 3. ASD Level 1 is considered the lowest classification of ASD and has less impact on the child's neurological functioning, therefore requires less support. Whereas, ASD Level 2 requires substantial support because children often encounter coping difficulties with changes in routine, and adversely impact their functioning. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) avers that ASD Level 3 is considered the most severe level and requires very substantial support because the child's repetitive behaviour restricts their ability to function. Data revealed that participants had no knowledge whatsoever that ASD had different levels, which adversely impacted the perceptions they had about children with ASD.

Inclusion of Children with ASD in Everyday Learning Activities during the National Hard Lockdown

White Paper 6 (DoE, 2001) advocates for the inclusion of all children in everyday learning activities, whether such activities are done indoors or outdoors, in school or away from school. The surfacing of COVID-19 and the extended closure of ECD centres to combat the spread of the pandemic during the hard lockdown, revealed startling ECCE educators' experiences.

The findings from this study reveal that ECCE educators had various perceptions of how to include young children with ASD in everyday education during the national hard lockdown.

Teacher A wrote: "It is difficult to teach these children because the parents themselves do not understand how to actually handle them'"

Teacher B responded to the question as follows:

I do not know how to teach these children, sometimes I just tell them to sleep on their mattresses because they disturb other children. So, when the centre was closed, I did not bother myself to give them any activities to do at home.

Although Teacher C barely expressed her views, she simply wrote "These children are frustrating me."

The findings suggest that ECCE educators' negative perceptions of children with ASD were exacerbated by their lack of theoretical and practical knowledge and understanding of including children with ASD in everyday education and especially during the periods of "severe turbulence" in education (Wood et al., 2022:16). Notably, sampled ECCE educators were underqualified and worked in a marginalised context.

"I have a Level 4 qualification, and when I was trained I was not taught about how to teach learners with special education needs and more especially autism. I only knew about it when I was teaching here" Teacher A lamented.

Such utterances also confirmed that their theoretical and practical knowledge of the inclusion of children with ASD was inadequate. Vorster, Kritzinger, Lekganyane, Taljard and Van der Linde (2022) confirm that educators lack the knowledge to optimise opportunities for children with ASD to benefit from early intensive intervention because of a lack of knowledge.

The results also reveal that ECCE educators struggled to create ideal environments that embraced responsiveness to individual children's strengths and challenges even when they were not in the classrooms.

In my classroom, I have children of mixed ages, they are between the ages of 2 and 4 years. I do have resources like charts, books, and playing dolls. But, when I teach them, I teach them all based on the ELDAs [early learning development areas] that I prepared for that week. When they go home, I do not give them any homework. (Teacher C)

Data revealed that sampled participants lacked expertise that allows reflective practices to scrutinise and revitalise the learning environment that accommodates the changing needs of children with ASD. Miles and Singal (2010) avow that undoubtedly, an inclusive learning environment is a product of adequately trained ECCE educators who possess perceived autism knowledge, experience working with autistic children, and a positive attitude toward inclusivity. Therefore, such frustrations were a result of their inadequate training and a lack of specialised teacher knowledge.

With regard to accommodating learners on the spectrum during the COVID-19 hard lockdown, Teacher B said:

Although I gave flip files to children with different activities that they had to do whilst at home, most of them did not draw anything as their parents do not know how to calm them down and make them talk or draw.

Teacher C confessed that she did not even try to give her children any work to do at home during lockdown because she was quite aware that her children were from poverty-stricken homes where most households did not even own a television set. Pillay et al. (2021) accentuate that due to differentiated socioeconomic standings, children with ASD suffer a harsh blow if parents are financially unstable as they require specialised attention and care including resources, like digital devices, that unleash their capabilities. To support this, Clasquin-Johnson and Clasquin-Johnson (2018:1) state that "autism is regarded as the most expensive disability" because rearing an autistic child is far costlier than rearing a typically developing child.

Opportunities for the Establishment of Collaboration among All Involved in the Education of Children with ASD

Based on one of the SEND principles, Hornby (2015) states that it is paramount that the establishment of communities based on collaboration among children, educators, families, other professionals and community agencies is forged. One of the questions was based on understanding the extent to which such collaborations were forged.

Teacher A wrote: "Yes, inspectors often come to our centre to check the well-being of children, more especially the cleanliness of the classrooms and centre premises. They usually speak with the principal, we then receive the report from her."

Teacher C wrote:

Since we moved to the DoE in April, the inspector from the DoE visited our centre. She wanted to check the policies that we use for teaching. I showed her the National Framework that I was given by the principal to use when I choose ELDAs. But, there are no specialists or therapists who have visited our centre.

Teacher B wrote: "If families can work with us, I think we can also be somehow able to help their children."

From the data generated, it was clear that there was a dire need to foster collaboration among all stakeholders involved in the education of young children. The findings suggest that the DBE has to spearhead the collaboration between the DBE and related entities such as the Department of Health (DoH) and the Department of Social Development (DSD). The former entity will assist in addressing the clinical challenges that these children faced during the lockdown period and other related crisis times as they often experience hypersensitivity and a lack of alertness when faced with unfamiliar situations. Subsequently, the former entity assists with alleviating random psychosocial challenges that might be experienced, including the facilitation of other necessities for children with ASD and ensuring comprehensive quality ECD programmes as advised by the National Integrated ECD Policy (RSA, 2015).

Exploring Opportunities for Innovative Teaching Pedagogy for Children with ASD

Teacher A expressed that she was willing to improve her teaching skills and learn more about how to teach learners with ASD.

She indicated that: "If I can be given an opportunity to learn how to use a computer when I am teaching, that will be a bonus."

Teacher B said: "Learning to teach using technology will be great because I have seen that these children are very good with technology, they even like to use cell phones a lot."

Teacher C wrote:

I think including technology when we teach is the best way. I attended a workshop on coding and robotics that was planned by the DoE. It was very interesting, but I need more time to know how I can teach using technology.

The rapid spread of COVID-19 was completely unexpected (World Health Organisation [WHO], 2020). This unprecedented, ubiquitous experience called for sophisticated planning coupled with ECCE educators' possession of technological pedagogic knowledge (TPACK). According to Mishra and Koehler (2006:1029), TPACK is "the basis of good teaching with technology and requires an understanding of the representation of concepts using technologies; pedagogical techniques that use technologies in constructive ways to teach content; knowledge of what makes concepts easy." Although TPACK for ECCE educators cannot be attained instantly and is also not practical due to the varied contexts in which they work, the findings imply that the DBE plays a significant role in training ECCE educators on how to employ creative inclusive pedagogy in their classrooms.

Conclusion

The aim of the study was to explore ECCE educators' perceptions of the inclusion of young children with ASD in everyday education and how their perceptions influenced the inclusion of these children in regular education during the COVID-19 period lockdowns.

It is worth noting that when this study was conducted, certain limitations were experienced. Limitations are regarded as potential weaknesses that are usually out of the researcher's control and are closely associated with the research design, theoretical underpinnings, and related other factors (Creswell & Creswell, 2017).

Since the participants were to engage with me after hours, they often rushed to leave without allowing me to elicit data that were required at that point and time. However, the use of reflective journals assisted in mitigating such challenges. Moreover, because only one ECD centre was sampled for the study resulted in limited data that might have been limited to the research site and its context only.

The primary focus on inclusivity is not solely based on "keeping" children with ASD. However, it is about taking their educational needs, inclusion as part of the equation, and emotional needs into consideration. There is a great need for quality ECCE educator training. Sanz-Cervera, Fernández-Andrés, Pastor-Cerezuela and Tárraga-Mínguez (2017) uphold that there is a positive relationship between the quality of teacher education programmes and learner success. Busby et al. (2012) advise that if adequate training and diverse clinical experiences are provided to serve children with autism, this might help to increase educators' sense of self-efficacy.

Opposingly, most ECCE educators are struggling to create inclusive learning environments. Nonetheless, their failure to create inclusive environments is a product of inadequate teacher training and experience, which also includes their attitude toward inclusivity. Educators require innovative inclusive pedagogy and positive attitudes that respond effectively to the diversity of children with special education needs. Since the DBE has taken over from the DSD, there is an enormous need to create robust platforms that allow educators to engage with parents and guardians of children with ASD.

These platforms should be similar to those that were developed to cater for virtual teaching and learning. Under normal circumstances, the specialists (educational psychologists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, and educators of children with ASD) decide on each learner's personal education plan (PEP) based on the assessment conducted by specialists.

The PEP is a model that describes how each learner's learning style will be accommodated in order to reach their optimum academic performance (Sugden, 2013). PEPs for children with ASD are designed and applied by educators based on each child's profile. Therefore, if the DBE can develop specialised training programmes or workshops focused on understanding ASD and effective parent engagement strategies, these programmes should provide educators with knowledge about the unique needs of children with ASD, communication techniques, behaviour management strategies and resources for supporting parents.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the ECCE educators from the sampled ECD centre for their willingness to participate in the study.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Alwee AI 2011. Crafting social engagement for community building: Towards a conscientised generation (Community Leaders Forum Special Paper). Singapore: National University of Singapore. Available at https://www.clfprojects.org.sg/qws/slot/u50226/06.%20Resources/6.1%20Media/Media%20Docs/2011/SPECIALPAPERFINAL.pdf. Accessed 31 October 2023. [ Links ]

American Psychiatric Association 2000. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR (4th ed). Washington, DC: Author. [ Links ]

American Psychiatric Association 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™(5th ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [ Links ]

Bipath K, Tebekana J & Venketsamy R 2021. Leadership in implementing inclusive education policy in early childhood education and care playrooms in South Africa. Education Sciences, 11(12):815. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11120815 [ Links ]

Burchinal M 2018. Measuring early care and education quality. Child Development Perspectives, 12(1 ):3- 9. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12260 [ Links ]

Busby R, Ingram R, Bowron R, Oliver J & Lyons B 2012. Teaching elementary children with autism: Addressing teacher challenges and preparation needs. Rural Educator, 33(2):27-35. https://doi.org/10.35608/ruraled.v33i2.416 [ Links ]

Clasquin-Johnson MG & Clasquin-Johnson M 2018. 'How deep are your pockets?' Autoethnographic reflections on the cost of raising a child with autism. African Journal of Disability, 7(0):a356. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v7i0.356 [ Links ]

Cohen L, Manion L & Morrison K 2018. Research methods in education (8th ed). London, England: Routledge. [ Links ]

Creswell JW & Creswell JD 2017. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa 2015. The South African National Curriculum Framework for children from birth to four. Pretoria, South Africa: Author. Available at https://www.unicef.org/southafrica/media/911/file/SAF-national-curriculum-framework-0-4-En.pdf. Accessed 31 October 2023. [ Links ]

Department of Education, Republic of South Africa 2000. National Education Policy Act (27/1996): Norms and Standards for Educators. Government Gazette, 415(20844):1-34, February 4. Available at https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/20844.pdf. Accessed 31 October 2023. [ Links ]

Department of Education 2001. Education White Paper 6: Special needs education. Building an inclusive education and training system. Pretoria: Author. Available at http://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=gVFccZLi/tI=&tabid=191&mid=484. Accessed 31 October 2023. [ Links ]

Department of Higher Education and Training, Republic of South Africa 2017. Higher Education Act (101/1997) and National Qualifications Framework Act (67/2008): Policy on Minimum Requirements for Programmes Leading to Qualifications in Higher Education for Early Childhood Development Educators. Government Gazette, 621(40750):1-48, March 31. Available at https://gazettes.africa/archive/za/2017/za-government-gazette-dated-2017-03-31-no-40750.pdf. Accessed 31 October 2023. [ Links ]

Engelbrecht P & Muthukrishna N 2019. Inclusive education as a localised project in complex contexts: A South African case study. Southern African Review of Education, 25(1):107-124. Available at https://www.saches.co.za/dmdocuments/SARE-Vol25-Issue1-Aug2019.pdf#page=107. Accessed 4 November 2023. [ Links ]

Erasmus S, Kritzinger A & Van der Linde J 2022. Families raising children attending autism-specific government-funded schools in South Africa. Journal of Family Studies, 28(1):54-69. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2019.1676292 [ Links ]

Guler J, De Vries PJ, Seris N, Shabalala N & Franz L 2018. The importance of context in early autism intervention: A qualitative South African study. Autism, 22(8):1005-1017. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361317716604 [ Links ]

Guler J, Stewart KA, De Vries PJ, Seris N, Shabalala N & Franz L 2023. Conducting caregiver focus groups on autism in the context of an international research collaboration: Logistical and methodological lessons learned in South Africa. Autism, 27(3):751-761. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613221117012 [ Links ]

Haimour AI & Obaidat YF 2013. School teachers' knowledge about Autism in Saudi Arabia. World Journal of Education, 3(5):45-56. https://doi.org/10.5430/wje.v3n5p45 [ Links ]

Harrison GD 2020. A snapshot of early childhood care and education in South Africa: Institutional offerings, challenges and recommendations. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 10(1):a797. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v10i1.797 [ Links ]

Hornby G 2015. Inclusive special education: Development of a new theory for the education of children with special educational needs and disabilities. British Journal of Special Education, 42(3):234-256. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8578.12101 [ Links ]

Landsberg E, Krüger D & Swart E (eds.) 2016. Addressing barriers to learning: A South African perspective (3rd ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Lee FLM, Yeung AS, Tracey D & Barker K 2015. Inclusion of children with special needs in early childhood education: What teacher characteristics matter. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 35(2):79-88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121414566014 [ Links ]

Leicht A, Heiss J & Byun WJ (eds.) 2018. Issues and trends in Education for Sustainable Development. Paris, France: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://doi.org/10.54675/YELO2332 [ Links ]

Lynch P & Lund P 2011. Education of children and young people with albinism in Malawi (Final Report). London, England: Commonwealth Secretariat. [ Links ]

Macupe B 2020. Education and learning in the time of Covid-19. The City Press, 12 April. [ Links ]

Mahadew A 2021. An inclusive learning environment in early childhood care and education: A participatory action learning and action research study. PhD dissertation. Durban, South Africa: University of KwaZulu-Natal. Available at https://ukzn-dspace.ukzn.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10413/20732/Mahadew_Ashnie_2021.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 31 October 2023. [ Links ]

Majoko T 2019. Teacher key competencies for inclusive education: Tapping pragmatic realities of Zimbabwean special needs education educators. Sage Open, 9(1):1-14. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018823455 [ Links ]

Mayton MR, Wheeler JJ, Menendez AL & Zhang J 2010. An analysis of evidence-based practices in the education and treatment of children with autism spectrum disorders [Special issue]. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 45(4):539-551. [ Links ]

Mazibuko N, Shilubane HN & Manganye SB 2020. Caring for children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder: Caregivers' experiences. Africa Journal of Nursing and Midwifery, 22(2):1-14. https://doi.org/10.25159/2520-5293/6192 [ Links ]

Mbarathi N, Mthembu ME & Diga K 2016. Early Childhood Development and South Africa: A literature review (Technical paper No. 6). Durban, South Africa: University of KwaZulu-Natal. Available at https://researchspace.ukzn.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10413/13338/Early%20Childhood %20Development_2016.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y. Accessed 31 October 2023. [ Links ]

Mesa S & Hamilton LG 2022. "We are different, that's a fact, but they treat us like we're different-er": Understandings of autism and adolescent identity development. Advances in Autism, 8(3):217-231. https://doi.org/10.1108/AIA-12-2020-0071 [ Links ]

Miles S & Singal N 2010. The Education for All and inclusive education debate: Conflict, contradiction or opportunity? International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14(1):1 -15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802265125 [ Links ]

Mishra P & Koehler JM 2006. Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6):1017-1054. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00684.x [ Links ]

Morrow W 2007. What is teacher's work? Journal of Education, 41:3-20. Available at https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/AJA0259479X_20. Accessed 31 October 2023. [ Links ]

Petty NJ, Thomson OP & Stew G 2012. Ready for a paradigm shift? Part 2: Introducing qualitative research methodologies and methods. Manual Therapy, 17(5):378-384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2012.03.004 [ Links ]

Pillay S, Duncan M & De Vries PJ 2021. Autism in the Western Cape province of South Africa: Rates, socio-demographics, disability and educational characteristics in one million school children. Autism, 25(4):1076-1089. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320978042 [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1996. Act No. 84, 1996: South African Schools Act, 1996. Government Gazette, 377(17579), November 15. Republic of South Africa 2015. National Integrated Early Childhood Development Policy. Pretoria, South Africa: Government Printers. Available at https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201610/national-integrated-ecd-policy-web-version-final-01-08-2016a.pdf. Accessed 31 October 2023. [ Links ]

Salleh MAM 2019. Inclusion of children with disabilities in general ECCE centres. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Special Education (ICSE 2019) (Vol. 388). France, Paris: Atlantis Press. Available at https://www.atlantis-press.com/proceedings/icse-19/125928849. Accessed 31 October 2023. [ Links ]

Sanz-Cervera P, Fernández-Andrés MI, Pastor-Cerezuela G & Tárraga-Mínguez R 2017. Pre-service educators' knowledge, misconceptions and gaps about autism spectrum disorder. Teacher Education and Special Education, 40(3):212-224. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406417700963 [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa 2022. Yearly archives: 2022. Available at https://www.statssa.gov.za/?m=2022. Accessed 6 June 2022. [ Links ]

Sternberg RJ & Zhang LF 2005. Styles of thinking as a basis of differentiated instruction. Theory into Practice, 44(3):245-253. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4403_9 [ Links ]

Sugden EJ 2013. Looked-after Children: What supports them to learn? Educational Psychology in Practice, 29(4):367-382. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2013.846849 [ Links ]

United Nations n.d. Sustainable development goals. Available at http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/news/communications-material/. Accessed 18 April 2020. [ Links ]

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 1994. World Conference on Special Education Needs: Access and quality (Final Report). Paris, France: Author. Available at https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000110753. Accessed 31 October 2023. [ Links ]

Vorster C, Kritzinger A, Lekganyane M, Taljard E & Van der Linde J 2022. Cultural adaptation and Northern Sotho translation of the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 12(1):a968. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v12i1.968 [ Links ]

Walton E & Engelbrecht P 2022. Inclusive education in South Africa: Path dependencies and emergences. International Journal of Inclusive Education :1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2022.2061608 [ Links ]

Wood R, Crane L, Happé F & Moyse R 2022. Learning from autistic educators: Lessons about change in an era of COVID-19. Educational Review:1-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2022.2103521 [ Links ]

World Health Organisation 2020. COVID-19 can be characterized as a pandemic. Available at https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19-11-march-2020. Accessed 18 April 2022. [ Links ]

Received: 15 November 2022

Revised: 20 June 2023

Accepted: 26 September 2023

Published: 31 December 2023