Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Education

versão On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versão impressa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.43 no.4 Pretoria Nov. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v43n4al597

ARTICLES

A humanitarian contribution: An effort to improve rural education and social transformation?

Ghamiet Aysen; Sanjana Brijball Parumasur

School of Management, Information Technology and Governance, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa ghamiet@catogroup.co.za

ABSTRACT

Due to the inequalities of the past in the apartheid era in South African, many communities, particularly in the rural areas, are still improvised. Children in these rural areas have no access to education - especially in the early childhood development (ECD) phase. To bridge this gap of unequal education, the Greater Edendale Muslim Society (GEMS) adopted a philanthropic approach and has applied a system of providing quality education in creches of excellence in the ECD phase in the community of Edendale. Built on the foundation of the theories of prosocial behaviour and the need to belong, this study stands testimony to the mindset that prosocial behaviour spurs on and triggers more helping behaviour that benefits a community and society and may, therefore, be effective in contributing to the development of a country as well as assist in eradicating years-old social ills and imbalances. Philanthropy is a diversification of organisational choices and actions as it is of wider social and community concerns. With this study we aimed to demonstrate that prosocial and helping behaviour fulfil an individual need and snowballs to contribute to a wider good, which in this case, is ECD and building a nation, economy, a country and its future. Clearly, since the 1994 democratic elections in South Africa, there has been a remarkable improvement of education in all sectors of society. There is still much to be done to improve the quality of life for all South Africans, particularly those previously disadvantaged who reside in the rural areas. From a developmental perspective, using a quantitative, positivist approach, through the use of structured questionnaires, we aimed to assess whether parents and teachers believed that the GEMS programme was providing unique education and promoting social transformation. The study was undertaken in 10 rural areas in Edendale (Pietermaritzburg) and consisted of a sample of 13 teachers and 293 parents using the cluster sampling method. Data were collected using a self-developed questionnaire of which the psychometric properties were statistically assessed and evaluated using descriptive and inferential statistics. The results show positive parent and teacher perceptions of the programme and its positive contribution to education and the transformation of society. Evidently, altruistic behaviour and the psychological need to belong has the potential to contribute to ECD and improving the ethical growth of the community, society and an emerging economy like South Africa.

Keywords: accessibility and affordability; altruism; early childhood development; rural education; social interaction; theory of the need to belong; theory of prosocial behaviour

Introduction

Background

Ninety per cent of brain development occurs prior to the age of 5 years, making these the most crucial years for adequate nutrition, support, and stimulation. Less than 16% of children in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa (SA) have access to early learning opportunities (Thanda, 2021). Despite the many economic gains made in South Africa since 1994, the divide between rich and poor remains. Even in post-apartheid SA, not everyone is given a fair opportunity to develop, realise their potential and contribute to the economy. This disparity is predominantly linked to the inequality in the investment for the development of young learners' human potential, skills and abilities. These are inextricably related to socio-economic status and economic inequality and the lack of social mobility of under-privileged people living in rural areas and lack support. Hence, the unique developmental window for toddlers under 5 years should be fully exploited. While SA is an emerging economy with a large human population, its development is hampered by the lack of skilled labour. This means the pressing challenge facing our government is how early learning opportunities can be scaled up quickly; not a 10-year strategy or a 20-year strategy, but a today-and-tomorrow strategy. This challenge cannot be addressed by the state alone and urgently needs wider efforts and initiatives. The problem is exacerbated by the fact that a large segment of the population resides in rural areas, are underprivileged, and their children lack early childhood education, care and development. This, in the long-term, denies these children the ability to effectively contribute to the labour market and to economic growth. Hence, the largest population in the developing economy of SA comes from disadvantaged, rural areas with limited opportunities for growth and the possibility to contribute to the reduction of economic disparity simply because of the poor standard and limited accessibility to early care, education and development. Evidently, for SA to succeed as an emerging economy and achieve economic growth, quality early childhood education is needed in order to enhance educational levels and promote the intellectual, social, psychological and economic development of all children such that they, as adults, are able to realise their potential and contribute effectively to their communities, organisations and country. Despite efforts, initiatives and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) addressing the dilemma of early childhood development (ECD) in SA, the Greater Edendale Muslim Society (GEMS) for example, it is imperative to assess these initiatives periodically to develop them and identify pitfalls. This mindset is reinforced by Richter (2016) who emphasises that economies grow when ECD is a priority.

In this article we define the context in SA, the challenges faced in the ECD phase, the role and experience in current initiatives like GEMS, the methodology adopted, the results and the recommendations made.

Background: Defining the Context in South Africa ECD includes programmes, experiences and activities aimed at enhancing and promoting the overall health and education of children under 9 years old (Preston, Contrell, Pelletier & Pearce, 2012). Statistics South Africa (2014) indicate that of the 5.1 million children between 0 and 4 years old only 1.6 million children attended a day care centre, ECD playgroup, or pre-primary school. Statistics South Africa (2010) further indicate that 61% of children in SA in 2009 lived below the poverty line (with a per capita income below R522 per month (which is equivalent to $33 United Sates Dollar (USD)). Unemployment is closely linked to this income poverty indicator - 36% of children live in households where none of the adults are employed. Gardiner (2008) mentions that the devastating acknowledgement of the effects of poverty were as follows:

• Children in the 0-1 age group constituted almost 10% of the population but only 15% of this number had access to ECD services.

• Between 58% and 70% of rural children lived below the poverty line.

• In rural communities 75% of children under the age of 5 suffered from malnutrition.

Gardiner (2008) further states that an estimated 33,000 Grade R teachers were needed nationally by 2010 and that in 2008 there were only 7,000 such teachers.

Challenges Faced in Early Childhood Development Evans and Schamberg (2009) state that living in poverty affects one's working memory as a result of chronically elevated physiological stress.

Based on the statement by Evans and Schamberg and many other researchers there is a need to ensure that all learners are given balanced meals approved by reputable dieticians on a daily basis to improve learning.

In 2012, it was reported that only 35.7% of children between birth and 4 years old attended ECD centres and enrolment in such centres is much lower in rural than in urban areas (Statistics South Africa, 2013). Engle, Black, Behrman, De Mello, Gertler, Kapiri, Martorell, Young and The International Child Steering Group (2007) attest that despite evidence, accessing formal ECD programmes after the age of 3 years old becomes important for toddlers to develop social skills and learning readiness and that only 52% of children 3 to 4 years old had access to care outside of the home. Evidence demonstrates that preschool attendance has a positive influence on reading and mathematics in Grade 4 (Moloi & Chetty, 2011).

Furthermore, the triangular link between every teacher, learner, and parent or caregiver is critical in the educational process for a successful ECD programme. Evidence shows that this is not implemented effectively - if not at all.

Mannak (2009) confirms that SA is one of the most unequal societies in the world today because apartheid engendered social and economic inequalities based on race, gender and social class. Despite the negativity, Lebusa and Xaba (2007) mention that there were many historically disadvantaged schools that performed well under challenging circumstances, especially with regard to teaching and learning resources.

It is difficult to understand that a condition of low educational level exists among the majority of South Africans, particularly in the ECD phase, although SA has the highest levels of public investment in education in the world. Education in South Africa (2016) reports that the SA Government spends about 7% of the gross domestic product (GDP) and 20% of total expenditure on education. Government spending on basic education during 2015/16 was estimated at $20.3 billion USD.

Pretorius (2014) established that the majority of South African children are from low socio-economic backgrounds, live in households where the literacy levels of the adults are very low and where there is almost no exposure to books or regular literacy practices, such as reading story books.

Many South Africans live in townships scattered throughout the country and access by road is difficult. One does not have to do a survey to witness this fact. There are only a few schools or creches in some areas but in most areas there are no amenities such as schools, creches, clinics, thus children growing up in these areas are not exposed to ECD education. There is no coordination or minimal activity by government to align educational activities among these rural areas because of the vastness and spread thereof. It goes without saying that children who grow up here are at a distinct disadvantage of being uneducated, exacerbating the South African problem of unemployment.

Elevated levels of household disorder, divorce, estrangement, and aggression are experienced by most people living in poverty. Thus, it is obvious that this situation contributes to problems in the ECD phase in SA.

Defining the Gap

In 2009 the Western Cape Department of Social Development commissioned Biersteker (2012) to do an audit of ECD and some of their findings are summarised as follows:

• The major challenge of providing ECD services in SA is that services are directed at children while parents' involvement is minimal. Parents thus lack the skills and resources to provide ECD services to their children while in the home.

• Although the provision of ECD services has improved, quality thereof remains poor. In poverty-stricken communities the quality of services is usually poor. Inequality thus persists because children from poor families cannot escape the poverty cycle.

• ECD centres, of which many receive state subsidy, are poorly managed - from an organisational and from a financial management perspective.

• The Department of Social Development (DSD) cannot adequately monitor the organisational or financial management and the quality of services in subsidised centres due to a lack of human and financial services.

In a survey sponsored by First National Bank in 2013 and carried out by Hwenha, some of the recommendations impacting on the challenges were as follows:

• To increase access to and improve the quality of ECD services to benefit all children in a manner that will continue to guide policy development and implementation.

• Corporate donors to focus on encouraging innovative models that can provide in the needs of children, families and communities.

• Ensure that people responsible to mould and prepare children for the future are trained properly and adequately.

• ECD teachers need coaching and mentorship.

• Children are exposed to poor sanitation and security as a result of inadequate infrastructure. Supporting the development of infrastructure in ECD is critical to make access to formal ECD services in the most remote and rural areas possible.

• The growth and development of children are affected by poor nutrition and health, thus, interventions regarding health and nutrition should make a lasting impact to the underprivileged in the rural areas (Hwenha, 2013).

The aforementioned clearly depict the need for altruistic and helping behaviour from the citizenry as the problems are societal and not merely governmental. Underlying altruistic and helping behaviour is the theory of prosocial behaviour, which is related to the psychological theory of the need to belong. Societies aim to attain greater cohesiveness and more effective integration of its citizens in order to facilitate well-being and improved interpersonal relationships. Therefore, it is imperative to assess ways in which better interpersonal relations can be achieved. Dovidio, Piliavin, Schroeder and Penner (2006) indicate that prosocial behaviour is influenced by environmental, social, biological, and psychological factors. In 2008, the researcher, a businessman, started the GEMS project in the rural area of Edendale, a township in the KwaZulu-Natal province of SA. After having read about and personally interacted with the Edendale community over many years, I initiated this project. My love for mankind and my ambition to assist in developing and educating the poorest of the poor motivated me to start GEMS.

The Role of the Greater Edendale Muslim Society (GEMS)

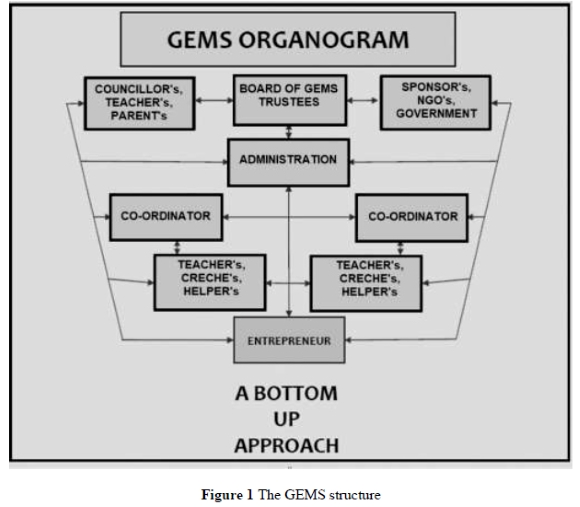

The aim of being involved was essentially to empower the entrepreneurs who ultimately became ECD teachers from the Edendale township with knowledge and skills to run their own businesses and to educate the learners, thereby addressing environmental factors. Most importantly, the intention was to employ an all-inclusive approach by coordinating the activities of all the crèches from a central office to ensure consistency in the methodology. As the children were to be the main beneficiaries of such activities, social factors would be addressed. The difference in the approach to this project was to have an office with an administrator to oversee the crèches and the staff to ensure that there was structure and accountability of the crèches affiliated to GEMS. GEMS set out to support total development and empowering of communities by engaging in sustainable planning in order to improve the quality of life by introducing and maintaining a culture of basic learning and education to meet the development challenges of a new SA. The GEMS structure is depicted in Figure 1.

The teachers and the assistants (helpers)

As depicted in Figure 1, GEMS is a bottom-up programme. The start of every crèche begins with an entrepreneur who realises the need and sees an opportunity. The entrepreneur and the community leaders in conjunction with GEMS, determine the need for the crèches. Bateman (2012) asserts that interventions in ECD have the potential to break the cycle of poverty and inequality. The entrepreneurs who are mostly uneducated and unemployed women who identify these crèches have no formal training in the ECD sector. Seventy per cent of the crèches recognised by the entrepreneurs emanate from mud huts in the rural areas of Edendale. Once the crèche owner meets GEMS' stringent requirements, they affiliate to GEMS on an annual basis. A feature of this programme is that the entrepreneurs are provided with the necessary training in the Montessori methods by attending regular scheduled classes presented by professional staff. The entrepreneurs obtain appropriate qualifications and become teachers who can offer quality education to the community from their premises or rented accommodation. Every teacher has an assistant also educated by GEMS. The aim is that these assistants eventually start their own crèche and so the cycle continues. When the teacher shows commitment to the children, GEMS assists the teacher to build a suitable crèche of brick and mortar. Fourteen such crèches have been built to date. Teachers can apply for government support and GEMS helps them in this regard, however, this process is very time consuming.

GEMS coordinators

The roles of the coordinators are many and varied. Coordinators visit the crèches daily to ensure that the learners are well fed, that they are safe, are in a clean environment and that quality education is presented. The coordinators assist and evaluate the teachers and their assistants and filter the relevant information to the administrator by writing a report and handing these to the office personally. English is also taught in the crèches. Howie (2003) states that despite the fact that English is the mother-tongue of less than 10% of the South African population, it remains the language of instruction. Due to the limited use of English outside the classroom, learners have little opportunity to develop language proficiency and their lack of English skills compounds their academic difficulties. The daily assessments of the GEMS teachers and assistants, which must be over 70%, are discussed monthly with the GEMS trustees so that key issues can be addressed immediately, thus ensuring follow through of all undertakings. The actions and motivations of the researcher, GEMS administrator, entrepreneur, teachers, community leaders and assistants are, therefore, rather altruistic and reflects helping behaviour which fundamentally depicts the theory of prosocial behaviour embedded in the psychological state of the need-to-belong theory.

GEMS administrator

As depicted in Figure 1, the administrator carries out the short- and long-term plans of GEMS. For the administrator to succeed in implementing these plans, he/she must understand the how, when and whom of the plan. Besides planning, the administrator ensures efficiency throughout the organisation. The Administrator is also responsible for leading the individuals within the organisation to accomplish a common set of goals which includes the delegation of authority, responsibility and the control of the coordinators. The administrator assures that GEMS is compliant in all forms and complies with all GEMS protocols, policies and procedures and that they are adhered to. He/She is also responsible for the finances and preparing the financials for the auditors. GEMS is transparent in their day-to-day activities and is audited yearly. In short, the administrator is responsible for running GEMS with the support of GEMS trustees and coordinators.

The Role of Parents, Teachers, Civic Leaders and Non-governmental Organisations (NGOs) The teachers, civic leaders, parents and NGOs together with the GEMS trustees constantly communicate with each other. Moyo, Francis and Ndlovu (2012) contend that through their participation community leaders are in a position to give a realistic picture of the reality on the ground. A positive feature of the programme is the input by the Islamic Educational Organisation of South Africa (IEOSA). The voluntary teacher training academy does the assessment of GEMS teachers and the children every quarter to ensure that the accredited syllabus that GEMS has in place is implemented. Meetings are held each month with the staff at GEMS to discuss all aspects of GEMS. The staff at GEMS is incentivised by them receiving a 13th cheque at the end of each year based on their performance during the year. The regular meeting of the teachers at GEMS displays unity, team spirit, confidence, motivates them to achieve, and builds a strong community presence. One of the greatest challenges facing South Africans is the lack of communities and the support system of a community. The Sunday classes and the interaction of the communities at the crèches or centres of excellence is one way of building communities.

GEMS - Non-profit organisation (NPO)

While societal ills prevail to limit people from achieving and displaying their true potential, people like the researcher, the founder and president of GEMS naturally and willingly possess and display altruistic behaviour. One such group of people is those at GEMS.

Theories of Prosocial and Helping Behaviour and Need to Belong

GEMS is a registered NPO and fulfils all the requirements of the South African law. There is a board of trustees of which 80% of the board members, including the chairperson and treasurer, are from the Edendale community. The GEMS trustees are responsible for raising funds because they get no financial assistance from the government to support the organisation. GEMS pays the teachers and their assistants a stipend every month to supplement their income and they assist in feeding the children a balanced meal twice a day. The GEMS trustees ensure that the teachers are continually motivated, regularly exposed to conferences, excursions and social events, where all staff and families gather, interact and enjoy each other's company, thus building unified communities. The GEMS trustees are always seeking innovative methods to stimulate the minds of the children such as "Wak-co-ball" (a sports and physical management programme), fun days and outings.

Many of the children come from families that struggle to put food on the table as unemployment is rife, and many families have lost bread winners, for some reason or another. Having a good meal is not just a question of survival, but ensuring a healthy individual who is alert in the classroom, keen to learn and able to give of his/her best. Accommodating and feeding the children would be of much less value if they did not engage in a structured learning process from which they would benefit. In this regard, GEMS has set about in a purposeful manner to ensure that their goals are achieved. Not only is the aim to prepare children for the formal learning of the education that they are to receive in the state schools, but also to promote the cognitive development of the individual to its fullest. GEMS also ensures that the children who have progressed to primary school and secondary school attend additional classes in the afternoon at the crèches where they were taught by the staff at GEMS. Parents of the children are taught basic literacy and are educated in these crèches on a Sunday morning. Regular meetings with parents and the community where matters of importance relating to the community are addressed are held in these crèches due to a lack of facilities in the rural areas. GEMS is linked with quality education and the community automatically associates themselves and the children with these crèches, which are seen as centres of excellence. The approach is well rounded.

Research Methodology

Research Design

Action and community-based research which has its origins in practical study and of which the outcomes are directed to benefit the communities was used. Involvement in this form of study lies in combining practice with theory by having the community actively participating in the survey.

Sample

The target population of this research comprised 13 teachers from 13 crèches. The target population for the parents comprised 320 parents of which 293 responded (91% of the target population). Cluster sampling was used and the cluster was defined in terms of parents in the Edendale area whose children attended the GEMS programme. Every element of the population had an equal chance of participation. According to Sekaran and Bougie (2010), the corresponding minimum sample size for a population of 320 is 175, thereby confirming the adequacy of the sample of 293 for this study. The adequacy of the sample was further determined using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (0.673) and the Bartlett test of sphericity (8571.950; p = 0.000), which respectively indicated suitability and significance. The results indicate that the normality and homoscedasticity preconditions were satisfied.

In Section A of the questionnaire aspects of the parents' life in rural areas were addressed. The parents' responses indicated that 45% of the group was between 26 years to 35 years old and that 92% were female. Furthermore, all the respondents were Black, 67% had completed secondary education up to Matric, 70% of the respondents were unemployed and 71% of the respondents earned between R0 and R500 per month.

The responses regarding the teachers indicated that 62% of the group was between 26 and 35 years old and that 92% were female. Furthermore, all the teacher respondents were Black, 46% had completed secondary education up to Matric and 46% had an National Qualifications Framework (NQF) Level 5 certificate which is accepted for university entrance. Seventy seven percent of the respondents were categorised as entrepreneurs and from those that were interviewed, 84% earned a salary between R900 and R1,500 per month.

Survey Instrument

Information was collected using self-developed questionnaires. Two sets of questionnaires were administered during the project, one for the teachers and the other for the parents, using a 1 to 5 point Likert scale. The teachers' perceptions were obtained to determine whether they benefited financially, emotionally, intellectually, and whether they believed that their skills and proficiency had been enhanced with the GEMS programme. The teachers' questionnaire comprised 15 items, which measured three dimensions, namely, teachers' perceptions of education and the environment (items 1-5), teachers' perceptions of excellence, ownership and progression (items 6-10) and teachers' perceptions of self-development and community development (items 11 -15).

The parents of the children, the majority of whom were unemployed and not educated were also given questionnaires to determine whether they felt that their children benefitted from the ECD training and whether the programme improved the quality of their and their children's lives. The parents' questionnaire comprised 20 items which measured four dimensions, namely, parents' perceptions of education and learning of their child (items 1 -5), parents' perceptions of accessibility and affordability of education for their child (6-10), parents' perceptions of social interaction as a result of the programme (items 11 -15) and parents' perceptions of their child's development (items 16-20).

Measures

The validity of the questionnaire given to parents was assessed using factor analysis. A principal component analysis was used to extract initial factors and an iterated principal factor analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) with an Orthogonal Varimax Rotation. Only items with loadings > 0.5 were considered to be significant. Furthermore, when items loaded significantly on more than one factor, only that with the highest value was selected. In terms of the dimensions of the study, four factors with latent roots greater than unity were extracted from the factor loading matrix for the parents' questionnaire (Factor 1: Parents' perceptions of education and learning of their child, Factor 2: Parents' perceptions of social interaction as a result of the programme, Factor 3: Parents' perceptions of accessibility and affordability of education for their child, and Factor 4: Parents' perceptions of their child's development). The reliability of the questionnaire for parents was determined using Cronbach's coefficient alpha. The overall reliability of the questionnaire was 0.958, thereby indicating a very high level of internal consistency of the items and hence, a high degree of reliability. The reliability of the dimensions were also computed separately for parents' perceptions of education and learning of their child (a = 0.902), accessibility and affordability of education for their child (a = 0.828), social interaction as a result of the programme (a = 0.889) and their child's development (a = 0.860), thereby reflecting a very high level of inter-item consistency for each dimension. Due to the small sample size for the teachers' questionnaire (n = 13), the validity and reliability could not be computed.

Administration

The teachers completed the questionnaire during a training session held in January 2016 in the GEMS office. The parents completed the questionnaire one at a time when they brought their children to the crèches or when they collected them in the afternoon. The majority of the parents were illiterate, so the bilingual teachers had to translate and capture their responses on the questionnaire.

Ethical Considerations

All the participants were informed about the nature and the aim of the research and all completed informed consent forms. The respondents were assured that their personal information would be treated with utmost confidentiality and that they could withdraw from the research at any time. The participants gave their permission that the research findings could be published.

Results

The perceptions of teachers in the GEMS programme were assessed by asking participants to respond to various dimensions using a 1 to 5 point Likert scale. The results were processed using descriptive statistics (cf. Table 1).

Table 1 indicates that teachers were totally satisfied with the ability of the GEMS programme to educate them and enhance the environment. In this regard, teachers' responses revealed that:

• They were able to educate themselves by being part of the GEMS programme.

• They were able to advance in their careers by being part of the GEMS programme.

• They enjoyed the GEMS programme because it provided them with challenging tasks that assisted their community.

• They enjoyed being part of a team striving to achieve the objectives of an organisation dedicated to service humanity.

• They were able to use the resources/anti-waste from their environment within the community for teaching.

Teachers also reflected complete satisfaction with the GEMS programme in bringing about excellence and enabling ownership and progression. In this regard the analysis showed that teachers were convinced that:

• They were afforded opportunities through the GEMS programme to progress in their careers, for example, from a helper to teacher to crèche owner to coordinator.

• The GEMS programme had enhanced their entrepreneurial skills and business acumen.

• The GEMS programme impacted positively on their families and personal life.

• They gained leadership skills which they could use to assist their communities.

• They had progressed in their lives by attending different courses in the educational field and these certificates/diplomas enhanced their curriculum vitae.

Teachers also indicated satisfaction with the GEMS programme in bringing about self-development and community development. In this regard, teachers were convinced that:

• They were inspired to be socially responsible and to assist with the needs of their community.

• The GEMS programme made them self-sufficient and independent.

• Through the GEMS programme they learnt to identify the ills and shortcomings within their communities and assist where they could.

• They were motivated and supported by the GEMS project to deal with and face any social, cultural and educational challenges that they encountered in their community.

Although positive, not all teachers were convinced that they had been given the opportunity to have their own business, that is, a crèche. This may be attributed to the fact that some teachers were still progressing through the ranks from teacher to crèche owner to coordinator.

The perceptions of parents of the GEMS programme were assessed by asking participants to respond to various dimensions using a 1 to 5 point Likert scale. The results were processed using descriptive statistics (cf. Table 2).

Table 2 reflects that parents viewed the GEMS programme extremely positively and in descending mean value, were convinced that the project enhanced the children's development (M = 4.959), facilitated the children's education and learning (M = 4.954), improved their social interaction (M = 4.954) and lastly, ensured accessibility and affordability of education for the children (M = 4.933).

While positive views of the GEMS programme were held by parents, in order to identify areas of improvement, item analyses were conducted to determine where total agreement was not achieved - which is reflected per dimension as follows:

• Children's education and learning: There is room for the GEMS project to make a further difference in the ECD phase of the child in the community.

• Accessibility and affordability of education for the children: There is room for making the GEMS programme to be more cost-effective.

• Social interaction as a result of the programme: There is room for the GEMS programme to enable parents to unite and share their concerns, problems, challenges and information about their children with other parents.

• The child's development: There is room for further assessments to be done with children to enhance their educational progress.

Hypothesis 1

Parents' perceptions of various aspects of the GEMS programme (children's education and learning, accessibility and affordability of education for the children, social interaction as a result of the programme, the child's development) significantly intercorrelated with each other (cf. Table 3).

Table 3 reflects that parents' perceptions of various aspects of the GEMS programme (children's education and learning, accessibility and affordability of education for the children, social interaction as a result of the programme, the children's development) significantly intercorrelate with each other at the 1% level of significance. Hence, hypothesis 1 may be accepted. The relationships between the sub-dimensions are also very strong.

Discussion

The study evaluated four key themes as follows: Children's education and learning Accessibility and affordability of education for the children

Social interaction as a result of the programme

The children's development

The findings of the study reflect positive parent and teacher perceptions of the GEMS programme and its contribution to education and the transformation of society by bridging the education divide and enhancing the moral development of the community. Evidently, parents believed that the GEMS programme contributed effectively to the children's education and learning, enhanced accessibility and affordability of education for the children in the Edendale area and promoted their development and social interaction. The strong intercorrelation among the sub-dimensions (children's education and learning, accessibility and affordability of education for the children, social interaction as a result of the programme, the children's development) indicate that any further improvement in any of the sub-dimensions will have a undulating and cumulative effect on remaining dimensions thereby enhancing the education, learning, social interaction and development of the children in the Edendale community. Hence, the parents' and teachers' recommendations pertaining to the Edendale community emanating from this study become pivotal to educational development and in bridging the educational divide. Evidently, altruistic behaviour spurs on further helping behaviour and can prove to be extremely fruitful in building a community, a generational cohort and hence, a country.

Recommendations

Based on the results of the study, the following recommendations are presented:

• The community and religious leaders should be encouraged and supported to start these crèches and create centres of learning and excellence.

• Altruistic, helping and prosocial behaviour should be encouraged and supported to develop these community members and assist them in contributing to social interaction and development.

• Critical to the programme is encouragement, coherence and support so that this programme can be developed throughout SA and the rest of Africa.

• In order to allow continuity and commitment, Government and NGOs must ensure that the teachers are continually motivated, regularly exposed to conferences, excursions and daily communication. The approach must be well coordinated.

• The Ministry of Education and NGOs needs to channel funds wisely with short and long-term goals. Inferior education and access to ECD training is problematic and this affects children's development. One cannot address these problems in the latter years of a child's schooling career and university.

• There are indeed strong prospects for fostering entrepreneurial customs at these schools. It is obvious from this programme that there are elements of innovativeness and entrepreneurship at these crèches and this must be harnessed and encouraged by the community leaders, NGOs and the government.

• Community leaders must inspire the unification of crèches in an area. It is not only the government's responsibility to do this but all of society.

• Strategies need to be both short- and long-term and there needs to be congruence between ends and means to ensure successful outcomes. Societies need to learn new habits in daily social interaction.

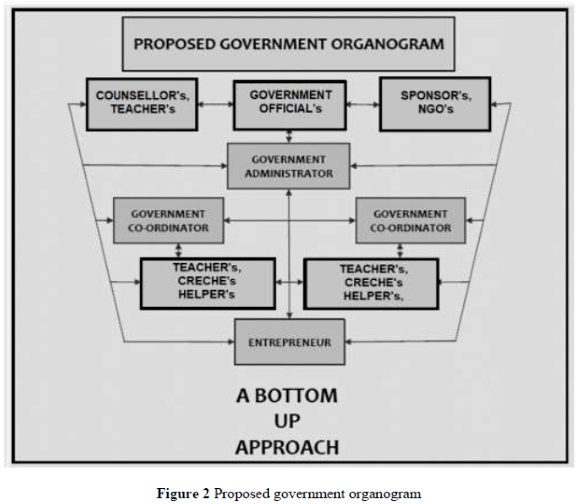

• The challenge is also to Government to chart a way forward by establishing centres of excellence and uniting existing crèches in the rural areas to use the GEMS model to enable the disadvantaged majority to access quality ECD education. It is recommended that the Government initiate a model that should be close to the one depicted in Figure 2, which is a bottom-up approach.

As depicted in Figure 2, the proposed Government model is similar to the GEMS model (cf. Figure 1). It is proposed that the government should establish offices in each rural area with qualified and competent staff and they should unite existing crèches, assist in start-up crèches by empowering the local community and supervising all the crèches in the area. There are many existing crèches scattered in various areas throughout SA. Government and NGOs must unite these institutions under one organisation in a rural area to ensure unity and that the crèches adhere to government policies, procedures and maintain protocol. It is a ssimple and inexpensive model and can be implemented within months. The government officials' actions must be such that the poorest of the poor benefit. Similarly, ward councillors in the rural areas should build communities by adopting the model depicted in Figure 3.

Building communities in the rural areas

The ward councillors or appointed representatives of the communities in the rural areas should take the leadership role and build communities as depicted in Figure 3.

Leadership in the communities must take ownership by firstly establishing crèches within their areas. This model is a bottom-up approach. Where crèches exist, they must be united under a single institution such as GEMS, a church, a mosque or NGO, but the crèche owners must not lose their independence. These crèches then become centres of excellence and all the communities' needs and activities are centred on these crèches or similar centres of excellence. Planning and matters relating to the everyday life within the community should be discussed regularly at these centres. Youth activities must also be conducted in these centres because accessibility to alternate amenities for the youth is not easily available in rural areas. Community leadership should emerge from these centres because of the bonding dynamics of the teachers and parents. Once the children leave the crèches they should be well groomed in the ECD phase and this education will ensure that they continue excelling in their youth and beyond. Once the youth have graduated from secondary school or university, they should have equipped themselves in life and they should be able to plough back their skills, finance and support to the community. This model is but one way of creating an energetic and prototypical community in rural areas so that these small communities become shining examples that other communities can follow. The cycle should continue as depicted in Figure 3.

Conclusion

Fundamental to the development of emerging economies like SA is the need for quality early childhood education and development, particularly in rural areas that suffer from educational and economic inequalities. A conscious effort to invest in rural areas has the potential of good returns, which will impact positively on communities. Empowerment can only result from a holistic process. The implementation of meaningful intervention strategies with a potential for a multiplier effect would go a long way to restoring hope and trust in rural communities and further augment the learners for ECD, is based on the premise that to have an educated nation equipped with quality education from the ECD phase, one needs to have teachers who are motivated, educated, progressive and gratified entrepreneurs. Equally true, parents want the best education for their children which is accessible, affordable, and which ensures their children's development in a vibrant community. The GEMS programme is one way of bridging this divide by contributing to social reformation. There is no doubt that the GEMS programme has contributed immensely to the well-being and intellectual and social development of the children under GEMS' care. This is a model that can, and should be replicated on as wide a scale as possible. These young children will have a decisive advantage when they get to primary school and even high school. No economy can grow by excluding any part of its people. An emerging economy like SA, which is not growing, cannot integrate all of its citizens in a meaningful way. Hence, the challenge is for the government and NGOs to chart a way forward by establishing centres of excellence and uniting existing crèches in the rural areas to use the GEMS programme to provide access to quality ECD education to the disadvantaged majority. The rippling effect in the developing economy of SA will then more likely be enhanced educational levels, labour productivity, and economic growth and development, thereby reversing many of the current inequalities.

Authors' Contributions

GA wrote the manuscript and provided data for the tables in the manuscript. SB also assisted with the data tables. GA conducted the interviews. Both SB and GA conducted all statistical analysis. Both SB and GA reviewed the final manuscript.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Bateman C 2012. Still separate, still unequal - Chid Gauge 2012. South African Journal of Child Health, 6(4):100-101. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAJCH.539 [ Links ]

Biersteker L 2012. Early childhood development services: Increasing access to benefit the most vulnerable children. In K Hall, I Woolard, L Lake & C Smith (eds). South African Child Gauge 2012. Cape Town, South Africa: Children's Institute, University of Cape Town. Available at https://ci.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/content_migration/health_uct_ac_za/533/files/sa_child_gauge2012.pdf. Accessed 30 November 2023. [ Links ]

Dovidio JF, Piliavin JA, Schroeder DA & Penner LA 2006. The social psychology of prosocial behavior. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Education in South Africa 2016. Available at http://www.southafrica.info/about/education/education.htm. Accessed 22 January 2016. [ Links ]

Engle P, Black MM, Behrman JR, De Mello MC, Gertler PJ, Kapiri L, Martorell R, Young ME & The International Child Steering Group 2007. Strategies to avoid the loss of development potential in more than 200 million children in the developing world. The Lancet, 369(9557):229-242. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60112-3 [ Links ]

Evans GW & Schamberg MA 2009. Childhood poverty, chronic stress, and adult working memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(16):6545-6549. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0811910106 [ Links ]

Gardiner M 2008. Education in rural areas (Issues in Education Policy Number 4). Johannesburg, South Africa: Centre for Education Policy Development. Available at https://www.saide.org.za/resources/Library/Gardiner,%20M%20-%20Education%20in%20Rural%20Areas.pdf. Accessed 30 November 2023. [ Links ]

Howie SJ 2003. Language and other background factors affecting secondary pupils' performance in Mathematics in South Africa. African Journal of Research in Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 7(1):1 -20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10288457.2003.10740545 [ Links ]

Hwenha S 2013. Increasing access and support to tertiary education: Lessons learnt from CSI-funded bursary programmes in South Africa. Available at https://dokumen.tips/documents/csi-that-works-increasing-access-and-support-to-tertiary-education.html?page=22. Accessed 22 January 2015. [ Links ]

Lebusa MJ & Xaba MI 2007. Prospects of fostering entrepreneurial customs at historically disadvantaged schools. Paper presented at the 5th International Conference on Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 24-25 October, Windhoek, Namibia. [ Links ]

Mannak M 2009. Report: South Africa most unequal society. Digital Journal, September. Available at www.digitaljournal.com/article/279796. Accessed 15 March 2014. [ Links ]

Moloi MQ & Chetty M 2011. Learner preschool exposure and achievement in South Africa (Policy Brief No. 4). Pretoria: South Africa Ministry of Education. Available at https://docplayer.net/20900077-Policy-brief-learner-preschool-exposure-and-achievement-in-south-africa-introduction-sampling-background-number-4-april-2011-www-sacmeq.html. Accessed 22 November 2023. [ Links ]

Moyo C, Francis J & Ndlovu P 2012. Community- perceived state of women empowerment in some rural areas of Limpopo Province, South Africa. Gender & Behaviour, 10(1):4418-4431. [ Links ]

Preston JP, Contrell M, Pelletier TR & Pearce JV 2012. Aboriginal early childhood education in Canada: Issues of context. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 10(1):3-18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X11402753 [ Links ]

Pretorius EJ 2014. Supporting transition or playing catch-up in Grade 4? Implications for standards in education and training. Perspectives in Education, 32(1):51-76. [ Links ]

Richter LM 2016. Economies grow when early childhood development is a priority. The Conversation, 6 December. Available at https://theconversation.com/economies-grow-when-early-childhood-development-is-a-priority-69660. Accessed 30 November 2023. [ Links ]

Sekaran U & Bougie R 2010. Research methods for business: A skill building approach (5th ed). Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa 2010. General household survey 2009. Pretoria: Author. Available at http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0318/P03182009.pdf. Accessed 30 November 2023. [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa 2013. General household survey 2012. Pretoria: Author. Available at http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0318/P03182012.pdf. Accessed 30 November 2023. [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa 2014. General household survey 2013. Pretoria: Author. Available at https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0318/P03182013.pdf. Accessed 30 November 2023. [ Links ]

Thanda 2021. Early childhood development. Available at https://thanda.org/early-childhood-development/?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIiuLVzMb95QIVxLHtCh3WdgkiEAAYAiAAEgISgfD_BwE. Accessed 22 November 2023. [ Links ]

Received: 2 October 2017

Revised: 3 December 2018

Accepted: 15 June 2023

Published: 30 November 2023