Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Education

versão On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versão impressa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.43 no.4 Pretoria Nov. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v43n4a2176

ARTICLES

Child rights education in Serbian schools

Jelena StamatovićI; Snežana MarinkovićI; Jelena Žunić CicvarićII

IFaculty of Education in Užice, University in Kragujevac, Užice, Serbia jelena.stamatovic22@gmail.com

IIChildren Rights Centre, Užice, Serbia

ABSTRACT

In this article we report on a study in which we examined the opinions and attitudes of teachers and learners on child rights education in Serbian schools. The participants included teachers and learners of primary schools from 7 municipalities in Serbia. The results show that teachers and learners held similar views on certain issues about child rights in school. Teachers held a positive attitude toward child rights education and recognised the importance of school in this process. They assessed their competency as insufficient, believing that child rights education was not sufficiently realised in schools, and supported training programmes in this area. The results also show teachers' views and suggestions for different areas of improvement. Learners, on the other hand, regarded teachers as the most responsible factor in child rights education, and their homeroom teachers as the greatest support in the protection of their rights. This study points to the need for a systematic approach to the implementation of child rights education in schools.

Keywords: child rights; child rights education; convention on the rights of the child; primary school

Introduction

The issue of child rights is a broad area approached from different perspectives and studied in different ways. Most authors have addressed the issue of child rights education, starting from the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child as the general framework. Some analyses have focused on the impact of the Convention on the national education policies of different countries (Hareket & Gülhan, 2017; Lundy, 2012). Thus, analysing research publications, Quennerstedt (2011) concludes that studies on child rights are, among other things, focused on human rights orientation, and the impact of the Convention on education/education policies. This is why, in most cases, child rights are studied and observed in an educational context. However, children can learn about their rights everywhere in the environment that respects said rights, which does not solely include formal education, but also their families, and the social environment in which children grow up and develop. If the environment in which they live is respectful of child rights, then such an atmosphere will transcend its initial area of impact and spread, and children will become more responsible and demonstrate those forms of behaviour that respect the rights of their peers and adults (Covell, Howe & McNeil, 2010). Familiarising children with their rights through formal and non-formal education helps raise their awareness of the importance of respecting child rights throughout society and improving their position in all segments of life (Stamatović & Żunić Cicvarić, 2019).

Through its broad scope of children's education, the education system has a great influence on children's development and the possibilities of achieving outcomes related to child rights. Another advantage associated with the education system is the fact that almost all children are part of this system and spend a large part of their childhood participating in it. In this process, they establish and maintain relationships with their peers and teachers, so it is perfectly natural to demand that the education system respects and protects child rights, and provides conditions where children will be able to learn about those rights, exercise, and "live" them (Stamatović & Żunić Cicvarić, 2019:87). However, learning about child rights is not enough. Relationships established between teachers and learners, and interpersonal relationships between learners themselves must be built on human rights values. This implies that the educational process, educational content, and teaching methods are based on the principles of respect for the child as a participant in the learning process, which is a great challenge for education (Quennerstedt, 2011).

Theoretical/Conceptual Framework and Literature Review

Child rights education is often defined as a way of promoting child rights in educational institutions. However, it should be emphasised that the key role in the implementation of child rights education is attributed to schools and teachers.

An overview of relevant literature reveals several directions for explaining the implementation of child rights education. One of them is the approach that underlines the legal framework as the basis of children's rights education, highlighting the need to standardise them, harmonise the curriculum with the standards, and define educational outcomes that directly refer to child rights (Howe & Covell, 2010; Jerome, 2016; Jerome, Emerson, Lundy & Orr, 2015). Other approaches stress the realisation of those rights in school and emphasise that schools should promote child rights. Some research supports the argument that schools promoting child rights is crucial because children who learn about and exercise their rights in the school environment will expand their knowledge and beliefs by beginning to respect the rights of others, will become more responsible and demonstrate behaviour based on the respect for the rights of their peers and teachers, and become more democratic and tolerant towards them (Alderson, 2008; Howe & Covell, 2005; MacDonald, Pluim & Pashby, 2012; Urinboyev, Wickenberg & Leo, 2016). The guiding principles that drive schools to introduce changes aimed at the implementation of children' s rights include inclusivity, a child-centred education process, democracy, protection, and active promotion of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. The implementation of these principles requires adaptation on the side of the school (conditions, staff, teachers, curriculum and syllabus, teaching methods, interpersonal relationships, etc.), and understanding of child rights. Specifically, schools should strive to help children learn about child rights by giving them the education that they are entitled to, and child rights by helping them exercise those rights in practice (United Nations Children's Fund [UNICEF], 2014). The trend observed in such schools includes an improved classroom atmosphere, and children's ability to exercise their right to active participation in their learning, which improves their motivation to deal with school life, and empowers them to participate in different activities and decisions concerning themselves (Allan & I'anson 2004; Lansdown, Jimerson & Shahroozi, 2014; Urinboyev et al., 2016).

The realisation of these principles largely depends on teachers. Learners are first introduced to their teacher at the very beginning of their education, because it is the teacher who directly interacts and works with them, creates an atmosphere for learning, and conveys knowledge on child rights. Therefore, it is very important what perceptions, beliefs and attitudes teachers hold toward these rights. Teachers are an important factor in shaping learner's behaviour, creating a favourable learning climate in the classroom, and designing educational activities in line with the context of children' s rights (Clair, Miske & Patel, 2012; Hareket & Gülhan, 2017). Some studies have shown that teachers who are not sufficiently prepared, or who don' t fully understand the context of child rights education do not support education based on child rights to a sufficient degree (Covell, 2007; Jerome, 2016; Jerome et al., 2015; Urinboyev et al., 2016). To overcome this obstacle, they need support during their initial education, but also throughout their professional teaching careers. When it comes to initial education, it is important that training programmes are primarily aimed at introducing students, future teachers, to their rights, possibilities of their realisation, and responsibilities. The syllabus of legal courses in basic teacher education reveal the connection between law and everyday life, but also shapes the development of one's beliefs and values, as well as knowledge about human and child rights (Jerome, 2016). When teachers have "lived and breathed" their rights, then they are more likely to create an atmosphere respectful of child rights in their teaching practice. The basis for such an atmosphere is one' s awareness of the need to respect child rights, which primarily arise from the respect for human dignity and child development that takes the needs of each child into account.

Teachers should receive support from the school management, which must be sensitive to these problems, and provide opportunities for teachers and other school employees to develop professionally and improve in all areas (Naidoo, 2019). It is the teacher' s role to base their classroom management on democratic principles, allowing learners to actively participate in learning and teaching processes. If both teachers and learners are familiar with, and if they learn about human and child rights together, both sides will understand the rights and responsibilities that these entail, thus promoting democratic interaction and a culture of human and child rights in the classroom (Carter & Audrey, 2000). However, the question is - what is the actual situation in practice, i.e. educational institutions? A review of relevant literature and research results has revealed numerous problems and deficiencies in practice. Quennerstedt (2011) emphasises that the perspective of child rights is largely absent from educational environments, and points to the factors in education that impede the realisation of child rights (Quennerstedt, 2011). We should also mention a widespread ignorance of the nature of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which causes teachers to resist its implementation in their teaching practice. Such teachers regard child rights as a threat to their ability to control the class, i.e. as a threat to their authority. The reason may lie in insufficient knowledge and preparation during initial education, or a traditional outlook on children and their abilities (Covell et al., 2010; Jerome, 2010). In addition, one of the reasons may also be the existence of a hidden curriculum in everyday school life which is the antithesis of the formal educational intent to support children's rights education in school and beyond (Thornberg & Elvstrand, 2012). The hidden curriculum implies that during formal education, children learn and adopt other things that are not included in the official curriculum: they accept values, attitudes and norms of behaviour that may not be fully in accordance with the prescribed goal of education, and may arise as a result of personal attitudes, norms and values of teachers as well as their competencies for (not) creating a democratic atmosphere for learning and development in classes and school in general.

There are some examples of "model schools" in practice, which are the results of research, with optimal working conditions based on the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and whose initiators and implementers are teachers who improve school and education in the context of children' s rights. It is precisely the support of such teachers, as well as the cumulative effect of their efforts aimed at observance of children's rights that can bridge the gap between the principles specified in the Convention and other international documents, and the actual situation in schools - the relationship between what should be and what is (Covell et al., 2010; Lundy, 2012; Tomasevski, 2006). When teachers accept the approach focused on child rights education and when it becomes an inherent part of their beliefs, they are ready to adapt even relatively unpromising and conservative curriculum frameworks to the context of child rights (Al-Nakib, 2012). However, there is little evidence that teachers are fully and systematically prepared to work within the context of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Namely, teacher education at university level in many European countries and beyond, doesn't provide enough competencies to enable future teachers to adequately address the issue of child rights (Thornberg & Elvstrand, 2012; Urinboyev et al., 2016). In a broader context, some authors state that countries often don' t possess mechanisms to ensure teachers' training on child rights, nor the ability to implement these principles in practice (Jerome et al., 2015). This is why numerous analyses and studies recommend a revision of the university curriculum for teacher education to develop the competencies for child rights, and highlight the need to improve and expand the knowledge of child rights of those teachers who already work in school through various training and professional development programmes (Shumba, 2003; UNICEF, 2014). Given the fact that Serbia has signed and ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the obligation of harmonising national legislation with the Convention, as well as the need to improve children's position in all segments of life, including education, have been realised. The realisation of child rights is fully supported by the legal and normative documents of the Republic of Serbia. However, few studies deal with the specifics of child rights in school and the role of teachers in that process in Serbia. Among those few are studies that address the realisation of participatory rights in school (Kravarušić, 2014; Vranješević, 2012), that examine child rights to protection from violence and bullying (Popadić, 2009), that examine different approaches to child rights education in school (Marinković, 2004; Pešikan, 2003), focus on the analysis of existing forms of human rights education and intercultural education within the civic education course (Zuković & Milutinović, 2008), and study the conditions and requirements of child rights education in primary schools (Stamatović & Żunić Cicvarić, 2019). This is why we decided to examine educational possibilities and situations for children's rights, as well as teachers' views on their role and engagement in this area through research.

Method

This study was part of broader research on the conditions and possibilities of child rights education in Serbia. We present and analyse results referring to child rights education in the school context primarily from the teachers' perspective, and in some segments, from the learners' perspective.

The study was empirical using a non-experimental approach. The aim was to examine the attitudes and opinions of teachers and learners about child rights education. The specific objective about teachers was focused on their attitudes toward the knowledge and information they possess and implement in their work in the context of knowledge about child rights, as well as their opinions on the possibilities for improving this area. The other specific objective was focused on the learners and their opinions about child rights, and whether they supported the implementation thereof in school or not.

The importance of this study lies primarily in the fact that it dealt with the area of child rights in the school context, on which very little Serbian research exists.

Sample

The research sample comprised teachers from seven primary schools, one from each of the seven participating Serbian municipalities, who taught both junior and senior grades in primary school. The final number of respondents in the sample was 231 teachers, of which 178 (77.05%) were class teachers (first to fourth grade), and 53 (22.95%) subject teachers (fifth to eighth grade). As for the learner sample, it included learners in the seventh and eighth grades (351 learners from seven primary schools). Learners and teachers were from the same schools, all of which were in urban areas.

The samples on which the research was conducted were selected among schools that serve as a model for the implementation of programme activities on child rights. The results obtained from these samples illustrate the state of child rights education in the selected schools and are used as a framework for modelling the project aimed at improving this area of education in schools where the research was conducted.

Research Instruments

We used two questionnaires in the study - one for teachers and the other for learners. The Questionnaire for Teachers included 16 items/questions. The first three items referred to general information about teachers, while the others referred to the research subject. The second section was a Likert-type scale (9 positively placed items) with a 5-point range of agreement, from 1 (I strongly disagree) to 5 (I strongly agree) used to measure attitudes about child rights education in school. We calculated the value of Cronbach' s alpha to analyse and determine the reliability of this part of the questionnaire. The value obtained was 0.71, which is greater than 0.60 and can be considered a satisfactory level of reliability. The Questionnaire for Pupils included items/questions that examined the state and needs of child rights education. For this research, data from the section of the research that referred to familiarising children with their rights from their own point of view were processed and analysed through questions that referred to providing information, knowledge and support to the realisation of child rights at school. The questions included multiple-choice questions and questions where learners were asked to rank the offered answers.

Data Analysis

The data obtained in this research were processed using the Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) 20.0. software. When it comes to statistical analysis methods, we used descriptive statistics (calculating frequencies and percentages, arithmetic mean, standard deviation and ranking). We also calculated the t-test of independent samples to compare arithmetic means of the two categories of teachers (teachers who taught junior grades (first to fourth grade) and teachers who taught senior grades (fifth to eighth grade)) defined as independent variables in the research. In this way we determined whether the attitudes of teachers who taught junior or seniors grades, differed.

Results

In the first section we present the results obtained from the teacher sample. We present the teachers' attitudes about children' s rights and learning about children' s rights in school, comparing the results on the learner age group variable and its modalities: teachers in junior grades, and teachers in senior grades.

The item that stood out, i.e. the attitude with the highest average value, was the importance of observing child rights in school. Teachers also expressed a high degree of agreement with the statements referring to their need to learn more about child rights. However, their agreement with the statements referring to the implementation of child rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child in education was significantly lower, although they largely agreed with the statement that the school was responsible for learners' knowledge and implementation of child rights and responsibilities (Table 1).

The results from Table 2 show that half of the respondents (more teachers who taught senior grades) stated that they did not receive any training or knowledge about child rights during initial teacher education.

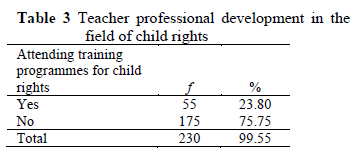

It is also clear that a large number of teachers did not participate in professional development programmes dedicated to child rights (Table 3).

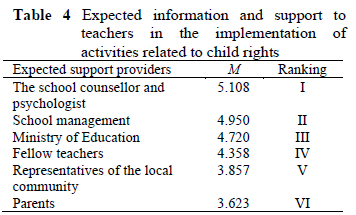

Teachers assessed people and organisations from which they expected to receive support and information on the implementation of activities related to child rights, rating them from 1 (most supportive) to 6 (leasst supportive). The school counsellor and psychologist were the highest-ranking providers, i.e., teachers expected them to be most supportive, followed by the school management, and the Ministry of Education. On the other hand, teachers didn't expect much support from their fellow teachers (they ranked fourth), and even less from parents (who ranked last) (Table 4).

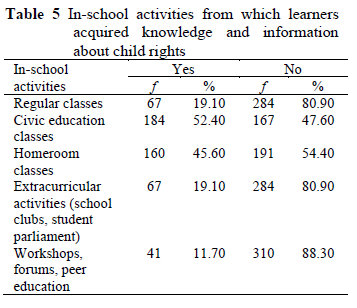

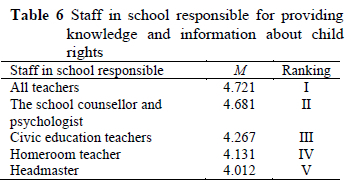

Finally, we wanted to discover the opinions of teachers about quality ways of addressing child rights in school. Having analysed their open-ended answers, we defined several categories for classifying the teachers' answers. The following survey results were obtained from the learner sample. Table 5 presents forms of in-school activities where learners acquired knowledge and information about child rights. The results show that teachers are responsible for providing knowledge and information about child rights (Table 6).

Discussion

The results from our study point to very important issues that have been the subject of other research. One of them was the fact that teachers had very positive attitudes toward the importance of child rights education. This has been confirmed by various research and insights which highlight the importance of the teachers' positive attitudes toward child rights, and the fact that such teachers are more willing to implement child rights in their teaching practice (Jerome, 2016; Shumba, 2003; Thornberg & Elvstrand, 2012). In addition, our study shows that teachers believed schools to be highly responsible for learning about and observing child rights. However, the ability to observe one's role and the ability to implement this role in the school practice are two very different things. It is positive that teachers regarded the school as an institution responsible for child rights education, but they must also view themselves and their work in the larger context of such school. Other research has shown positive effects achieved by schools whose teaching practice is fully based on the principles of child rights education, and which actively implement child rights and principles of the Convention, relying on teachers for its implementation (Covell et al., 2010; MacDonald et al., 2012; UNICEF, 2014). Our results show that the majority of teachers agreed that learning about child rights should be implemented in the regular curriculum and that the organisation and implementation of teaching should be based on the principles of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. We can assume that such attitudes arise from insufficiently developed competencies for the implementation of children' s rights education. Teachers' attitudes show that they should possess more knowledge about child rights and that such knowledge should be acquired during initial teacher education. Almost half of the respondents stated that they acquired absolutely no knowledge or information about child rights during their initial education. Other research yielded similar results, stating that very little attention is paid to learning about child rights and the preparation of teachers for their future profession (Covell, 2007; Hareket & Gülhan, 2017). However, research by Stamatović and Żunić Cicvarić (2019) shows that teachers do not see the need to implement learning about child rights into the courses available in initial teacher education. The situation is similar when it comes to professional teacher development in this field. About two-thirds of the respondents in our survey did not attend any in-service training programmes related to child rights. Teachers should implement their knowledge about child rights acquired through in-service training programmes in their teaching practice, and in the authentic classrooms where they teach (Huss, 2007; MacDonald et al., 2012). Similar results indicate that it is this insufficient knowledge of child rights and the possibility of implementing it in one' s teaching practice that creates resistance among teachers, and gives rise to the attitude that child rights may pose a threat to one' s authority in the classroom (Harcourt & Mazzoni, 2012; Howe & Covell, 2005; Urinboyev et al., 2016). On the other hand, our results also show that, although teachers believed that they didn't possess sufficient knowledge of child rights, they disagreed about the attitude that there was resistance among teachers regarding the Convention on the Rights of the Child and its implementation.

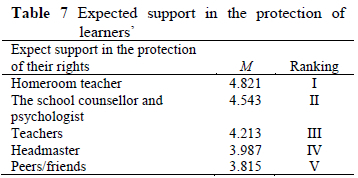

Schools that advocate child rights education and implement the principles of the Convention imply mutual respect and cooperation, primarily between teachers and learners, but also among teachers, between teachers and other employees -the emphasis is on the support and learning at all levels (UNICEF, 2014). The results of our study show that teachers expected support on children's rights education, primarily from the school counsellor and psychologist (see Table 7). The involvement of school psychologists includes the implementation of various activities and processes defined in the Convention on the Rights of the Child (promoting children's participation in decision-making in life and school, developing and maintaining a sense of security in the family and school, etc.), so it can be argued that they encourage and support the realisation of certain rights of the child (Lansdown et al., 2014). School psychologists and counsellors are responsible for protecting children at school, providing support to their development and growth, as well as for promoting the positive adaption of young people in the school and social environment, which certainly implies a positive environment that respects child rights (Theron, Liebenberg & Malindi, 2014).

The school management's support to teachers in the promotion and implementation of child rights education ranked second, followed by support from the Ministry of Education, and finally, support from one' s fellow teachers, representatives of the local community and parents. Teachers regard the school management as a reliable support structure in the implementation of child rights education. That kind of support may be expected in the field of a normative framework and material and technical resources needed for the implementation of child rights. The issue of the realisation of child rights in the education system is roughly defined through legal and normative documents that are legally binding on teachers and schools. The authors of these documents are state institutions, so they regards the support by the Ministry of Education in this regard as a complement to that. Interestingly, teachers don't expect much support from their fellow teachers in the promotion and implementation of children' s rights education.

Various studies show that child rights education has to do with teacher's personal beliefs and values, and that differences among them in that respect may be significant, which is a threat to cooperation and support (Hareket & Gülhan, 2017; Howe & Covell, 2005; Jerome, 2010). Jerome (2016) even points out that those teachers who, from their beliefs and knowledge, try to promote educational strategies that rely on the Convention in those school environments where child rights education comes down to empty formality, are probably considered hypocrites.

Teacher respondents provided insight into the possibilities and areas that should be changed or improved to implement child rights education in schools. Their proposals were classified into several categories: complementing the primary school curriculum with courses and content related to child rights (introducing compulsory elective courses that will address child rights and responsibilities; expanding the content of existing courses with topics related to child rights); planning and implementing extracurricular activities in school (organising school clubs; counselling sessions by homeroom teachers, school counsellor and psychologist; workshops for learners; peer education on child rights; participation in the learners parliament); increased learner participation (planning and defining mechanisms for making and implementing decisions that apply to them in cooperation with learners); additional in-service training for teachers in the field of child rights (arranging seminars, forums, professional conferences).

The results we obtained from the learner sample are discussed under several items: providing information and learning about children' s rights from the learners' perspectives: who is most responsible for teaching them about child rights; and from whom do learners expect most support regarding the protection of their rights.

Learners responded that they obtained most information and knowledge about child rights in civic education classes, as well as homeroom classes which aren't regarded as regular classes. Every fifth learner stated that they learned something about child rights in regular classes. Based on these results, we can see that learners didn' t recognise the possibility of learning about child rights in class. Results of other studies indicate the importance of child rights in the classroom, an active student approach to learning, a democratic atmosphere, and the establishment of more democratic relationships between teachers and learners (Urinboyev et al., 2016). The importance of creating an open school climate where teachers and learners may openly discuss and actively learn about children' s rights is emphasised as well (Thornberg & Elvstrand, 2012).

Although these studies underline the importance of learning about child rights in the classroom, there aren't many results that confirm that such an approach is systematically implemented in schools, unless we are talking about schools that purposefully follow the principles of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNICEF, 2014). A good example is a school in Hampshire, England, that implements a specific-purpose curriculum of which the framework is based on children's rights (Covell et al., 2010). The issue of the realisation of child rights in the education system is roughly defined through legal and normative documents that are legally binding for teachers and schools. The authors of these documents are state institutions, so they regard the support of the Ministry of Education on this matter as a complement to that.

In our study learners considered teachers to be the most responsible for providing information and knowledge about child rights, followed by school counsellors and psychologists, civic education teachers, homeroom teachers, and finally, the headmaster. The situation is somewhat different when it comes to the expected support in the protection of their rights. Learners place the most trust in their homeroom teachers who are not solely focused on teaching, but also on pedagogical activities about the class, and each learner, followed by the school counsellor and psychologist whom learners identified as responsible for informing them about child rights, other teachers, the headmaster, and finally, their peers. Promoting schools focused on child rights requires active learner participation and emphasises their position and power in the protection and exercise of child rights, which is confirmed by Allan and I'anson (2004). Learners need to feel safe and believe that schools protect and promote their rights.

Conclusion

Normative frameworks arising from the Convention on the Rights of the Child, schools focused on education respectful to the Convention, competency of teachers and mutual support and democratic relationships in school are necessary for the successful promotion and implementation of children' s rights in school. The school and its teachers then become important advocates of children' s rights, i.e. they continuously provide knowledge, support and guide learners toward exercising their rights (Stamatović & Żunić Cicvarić, 2019).

Our study presents just a small fraction of child rights education from the point of view of teachers and learners in Serbian primary schools. The results show the current situation and point out obvious problems in this area. The problems identified include insufficient competencies of teachers for the implementation of child rights in education as a whole (classes, extracurricular activities, relationships with learners) that they should receive during their initial teacher education, or in specialised in-service training programmes. In addition, the curriculum is deficient in content related to child rights, and in-school activities aimed at promoting children' s rights are limited. Research results indicate that the framework of child rights education largely involves routine and formal activities. The positive attitudes of teachers regarding child rights education, their self-assessment about a perceived lack of knowledge in this area, as well as their understanding of the importance of the school in promoting child rights education can be characterised as resources that provide opportunities for schools to improve in this area. The thing that stands out and that may potentially change the current situation is the positive attitudes of teachers toward child rights education and their self-assessment about a perceived lack of knowledge in this area, as well as their recognition of the school as the most important factor in the promotion of child rights education. These results indicate the need for changes in initial teacher education, i.e., the need to expand and improve the university curriculum to help future teachers develop competencies in child rights education. Moreover, there is a need for more professional development programmes that will also develop such competencies of teachers who already work in schools. Teachers recognise the possibilities for change and the areas where change should occur, and indicate potential solutions and ways to improve in these areas.

Results obtained by examining learners' opinions have many things in common with teachers' opinions in terms of insufficient implementation of child rights education, i.e. introducing and familiarising learners with child rights sporadically and inadequately. Learners consider teachers and homeroom teachers to be the most responsible for teaching them about and protecting their rights. This confirms what previous research has shown - that we need a systematic and planned implementation of child rights education, in other words, a comprehensive approach to implementation at all levels of education. This can be a direction for the improvement of Serbian education in this regard.

It would be interesting, as a recommendation for further research, to examine child rights education and the implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child from the perspective of instruction itself, it's planning, organisation and realisation, and interpersonal relationships in school at all levels.

Authors' Contributions

JS, SM, JŻC wrote the manuscript and conducted instruments for research purposes; the scaled survey was conducted by JŻC; JS conducted all statistical analyses. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

References

Alderson P 2008. Young children 's rights: Exploring beliefs, principles and practice (2nd ed). London, England: Jessica Kingsley. [ Links ]

Allan J & I'anson J 2004. Children's rights in school: Power, assemblies and assemblages. The International Journal of Children 's Rights, 12(2):123-138. https://doi.org/10.1163/1571818041904335 [ Links ]

Al-Nakib R 2012. Human rights, education for democratic citizenship and international organisations: Findings from a Kuwaiti UNESCO ASPnet school. Cambridge Journal of Education, 42(1):97-112. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2011.652072 [ Links ]

Carter C & Audrey O 2000. Human rights, identities and conflict management: A study of school culture as experienced through classroom relationships. Cambridge Journal of Education, 30(3):335-356. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640020004496 [ Links ]

Clair N, Miske S & Patel D 2012. Child rights and quality education: Child-Friendly Schools in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). European Education, 44(2):5-22. https://doi.org/10.2753/EUE1056-4934440201 [ Links ]

Covell K 2007. Children's rights education: Canada's best kept secret. In RB Howe & K Covell (eds). A question of commitment: Children 's rights in Canada. Waterloo, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. [ Links ]

Covell K, Howe RB & McNeil JK 2010. Implementing children's human rights education in schools. Improving School, 13(2):117-132. https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480210378942 [ Links ]

Harcourt D & Mazzoni V 2012. Standpoints on quality: Listening to children in Verona, Italy. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 7(2):19-26. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693911203700204 [ Links ]

Hareket E & Gülhan M 2017. Perceptions of students in primary education department related to children's rights: A comparative investigation. Journal of Education and Learning, 6(2):41-52. https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v6n2p41 [ Links ]

Howe RB & Covell K 2005. Empowering children: Children 's rights education as a pathway to citizenship. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press. [ Links ]

Howe RB & Covell K 2010. Miseducating children about their rights. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, 5(2):91-102. https://doi.org/10.1177/1746197910370724 [ Links ]

Huss JA 2007. Using constructivist teaching to shift the paradigm for pre-service philosophy of education statements. Essays in Education, 21(1):69-76. Available at https://openriver.winona.edu/eie/vol21/iss1/7?utm_source=openriver.winona.ed u%2Feie%2Fvol21%2Fiss1%2F7&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPage. Accessed 11 December 2020. [ Links ]

Jerome L 2010. From children's rights to teachers' responsibilities - identifying an agenda for teacher education. In P Cunningham & N Fretwell (eds). Lifelong learning and active citizenship. London, England: Children's Identity & Citizenship in Europe (CiCe). Available at https://scholar.googlexorn/scholar?hl=sr&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=From+children%E2%80%99s+rights+to+teachers%E2%8 0%99+responsibilities+%E2%80%93+identifying+an+agenda+for+teacher+education++Lee+Jerome&btnG. Accessed 5 December 2020. [ Links ]

Jerome L 2016. Interpreting children's rights education: Three perspectives and three roles for teachers. Citizenship, Social and Economics Education, 15(2):143-156. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047173416683425 [ Links ]

Jerome L, Emerson L, Lundy L & Orr K 2015. Teaching and learning about child rights: A study of implementation in 26 countries. Geneva, Switzerland: UNICEF. Available at https://www.unicef.org/media/63086/file/UNICEF-Teaching-and-learning-about-child-rights.pdf. Accessed 20 November 2023. [ Links ]

Kravarusić V 2014. Stavovi učenika o proevropskim i nacionalnim vrednostima [Students' attitudes about pro-European and national values]. In I Cutura & V Trifunović (eds). Škola kao činilac nacionalnog i kulturnog identiteta i proevropskih vrednosti: Obrazovanje i vaspitanje - tradicija i savremenost. Jagodina, Serbia: Pedagoski Fakultet. [ Links ]

Lansdown G, Jimerson SR & Shahroozi R 2014. Children's rights and school psychology: Children's right to participation. Journal of School Psychology, 52(1):3-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2013.12.006 [ Links ]

Lundy L 2012. Children's rights and educational policy in Europe: The implementation of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Oxford Review of Education, 38(4):393-411. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2012.704874 [ Links ]

MacDonald A, Pluim G & Pashby K 2012. Children 's rights in education: Applying a rights-based approach to education. Toronto, Canada: UNICEF. [ Links ]

Marinković S (ed.) 2004. Decija prava i udźbenik [Child rights and textbook]. Beograd: Zavod za udžbenike i nastavna sredstva. [ Links ]

Naidoo P 2019. Perceptions of teachers and school management teams of the leadership roles of public school principals. South African Journal of Education, 39(2):Art. #1534, 14 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v39n2a1534 [ Links ]

Pešikan A (ed.) 2003. Obrazovanje i ljudska prava [Education and human rights]. Podgorica, Montenegro: Centar za ljudska prava. [ Links ]

Popadić D 2009. Nasilje u skolama [Violence in schools]. Beograd, Serbia: Institut za psihologiju. Available at http://www.mpn.gov.rs/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/nasilje-u-skolama-za-web.pdf. Accessed 15 October 2019. [ Links ]

Quennerstedt A 2011. The construction of children's rights in education - a research synthesis. The International Journal of Children' s Rights, 19(4):661-678. https://doi.org/10.1163/157181811X570708 [ Links ]

Shumba A 2003. Children's rights in schools: What do teachers know? Child Abuse Review, 12(4):251 -260. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.800 [ Links ]

Stamatović J & Żunić Cicvarić J 2019. Child rights in primary schools - the situation and expectations. CEPS Journal, 9(1):83-102. https://doi.org/10.26529/cepsj.661 [ Links ]

Theron L, Liebenberg L & Malindi M 2014. When schooling experiences are respectful of children's rights: A pathway to resilience. School Psychology International, 35(3):253-265. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142723713503254 [ Links ]

Thornberg R & Elvstrand H 2012. Children's experiences of democracy, participation, and trust in school. International Journal of Educational Research, 53:44-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/jijer.2011.12.010 [ Links ]

Tomasevski K 2006. The state of the right to education worldwide: Free or fee (Global Report). Available at https://www.right-to-education.org/sites/right-to-education.org/files/resource-attachments/Tomasevski_Free_or_fee_Global_Report_2006.pdf. Accessed 17 December 2020. [ Links ]

United Nations Children's Fund 2014. Child rights education toolkit: Rooting child rights in early childhood education, primary and secondary schools. Geneva, Switzerland: UNICEF Private Fundraising and Partnerships Division. Available at https://www.unicef.org/media/63081/file/UNICEF-Child-Rights-Education-Toolkit.pdf. Accessed 25 November 2020. [ Links ]

Urinboyev R, Wickenberg P & Leo U 2016. Child rights, classroom and school management: A systematic literature review. The International Journal of Children 's Rights, 24(3):522-547. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718182-02403002 [ Links ]

Vranjesević J 2012. Razvojne kompetencije i participacija dece: Od stavrnog ka mogućem [Development competences and participation of children: From the aging to the possible]. Beograd, Serbia: Ućiteljski fakultet. [ Links ]

Zuković S & Milutinović J 2008. Škola u duhu novog vremena: Obrazovanje za različitost [School in the spirit of the new age: Education for diversity]. Nastava i Vaspitanje, 57(4):530-538. [ Links ]

Received: 28 December 2020

Revised: 14 June 2023

Accepted: 16 August 2023

Published: 30 November 2023