Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Education

versão On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versão impressa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.43 no.4 Pretoria Nov. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v43n4a2158

ARTICLES

The impact of education tailored for critical listening on the critical listening skills of seventh-grade students

Nahide İrem Azizoğlu; Alparslan Okur

Turkish Language Education Department, Faculty of Education, Sakarya University, Sakarya, Türkiye azizoglu@sakarya.edu.tr

ABSTRACT

Critical listening is not only a complex whole that covers different skills but also 1 of the skills areas we mostly need in today's society. The aim of this research was to determine the effects of education tailored for critical listening on the critical listening skills of 7th-grade students. For this purpose, we applied the relevant education in two 7th-grade classes in Sakarya, Türkiye. This was a quasi-experimental study and it was completed in 40 course hours. The experimental group received training on critical listening skills and critical listening texts and questions were used to collect quantitative data. We found a significant difference in the post-test scores of the experimental group in terms of total critical listening scores.

Keywords: critical listening; education language; language skills; listening

Introduction

In today's society, the way to achieve accurate and reliable information is through questioning, critically examining what you hear, and making assessments. Hence, critical listening skills have become a key skill that individuals should possess (Grosser & Nel, 2013; Moon, 2008). This has also been highlighted in the 2019 Turkish curriculum. Accordingly, one of the aims of the curriculum is "to ensure that students can do research, interpret data, access information, analyze information before using it, fully understand what they read, question it, and perform critical evaluations" (Millî Eğitim Bakanliği [MEB], 2019:3), focusing on critical listening and assessment skills. Research on critical listening has increased from 1940 to 1980. However, there is a limited number of recent studies on the subject (Azizoğlu, 2022). As critical listening is a relevant skill that individuals need (Crawford, 2009; Yore, Bisanz & Hand, 2003), conducting research on how to teach this skill is crucial. Therefore, with this research we focused on critical listening skills. The Turkish curriculum includes critical listening as one of the methods of listening (MEB, 2019). However, the curriculum includes no explanation about critical listening and gives no information about its implementation. Furthermore the Turkish textbooks that were prepared in line with this curriculum have not significantly focused on critical listening (Azizoğlu, 2022). Thus, as a relevant skill that individuals need, researching critical listening can fill this gap in Turkish education. Also, such studies can provide information and resources to teachers and curriculum developers regarding the teaching of this skill. Within the scope of critical listening skills, we discussed the following subjects: determining the subjectiveness/objectiveness of the text, determining whether the text is biased, determining the subject and the main idea of the text, recognising propaganda, evaluating the text's subject and drawing conclusions, evaluating consistency within the text, evaluating the evidence in the text, and evaluating the speaker (Azizoğlu & Okur, 2021). The impact of a teaching process prepared for these subjects on students' critical listening skills was examined. The Turkish curriculum includes critical listening as a method of listening for the seventh and eighth grades of secondary school. Critical listening involves some other skills that could be classified as high-level skills, like analysing, synthesising, and evaluating (Carkit, 2018), so it is not included in the fifth or sixth grades. Due to the fact that the eighth-grade curriculum is intense and these students take the high school entrance exam at the end of the year, it was decided to conduct this research with seventh-grade students.

Background

Research on the concept of critical listening began in the 1940s and numerous studies were conducted on the subject until the 1980s (Azizoglu & Okur, 2021). This can be explained by the social and political structure of that period. During World War II, a lot of research was performed on the subject, because the United States of America (USA) planned to provide training on critical listening to both soldiers and civilians (Brewster, 1956).

Various definitions of critical listening commonly include concepts such as questioning, evaluation, and comparison. Lundsteen (1963:18) defines critical listening as "criticizing a narrative, comparing ideas, making decisions, and applying them within the framework of objective evidence on the subject"; Y Dogan (2007:36) defines the concept as "determining the speaker's purpose and analyzing elements of bias, emotion, or propaganda in the narrative"; Trace (2013:68) defines it as "a system that consists of examining ideas, making connections between them, and examining their importance."

Studies on critical listening deal with various skills covered by critical listening. Beery's (1946) classification focuses on skills of evaluating expressions of evidence within the text and the source and examining the narrative. Early (1954) and Groom (1970) highlight the concepts of recognising propaganda and marketing techniques. Devine (1961) was concerned with determining biased expressions within the text and the purpose of the text. Davis-Rice (1982) and Lundsteen (1963) described critical listening as the determination of a text's purpose and its analysis. Akyol (2006) and Yalçın (2006) emphasise the importance of determining a text's purpose and reaching conclusions accordingly. Celepoğlu (2012) explains the necessity of examining the accuracy and consistency of information presented in a narrative. B Doğan (2017) emphasises that a critical listener should recognise the use of persuasive and deceptive language. Carkit (2018) determined the subdimensions of critical listening skills as critical interpretation, analysis, questioning, comparison, and evaluation. Azizoglu and Okur (2021) define the scope of critical listening as follows: determining the subjectivity/objectivity of the text, determining bias, determining the subject and the main idea of the text, recognising propaganda, evaluating the subject of the text and drawing conclusions, evaluating the consistency of the text, and evaluating evidence and the speaker. Recent research on critical listening seems to be quite rare. This may be due to the fact that critical listening was considered a skill of significance during the period of World War II. However, it is a relevant skill and this makes it necessary to conduct new research on the subject.

Research on the teaching of critical listening has included various practices with different groups within the scope of critical listening as defined by the researchers. Devine (1961) conducted such practice with ninth-grade students on determining directions and purpose within a text. Laurent (1963) performed a teaching process on critical listening with fifth and sixth-grade students based on propaganda, objective and subjective language use, and making inferences from the text. Lundsteen (1963) covered the topics of determining the speaker' s purpose, the use of propaganda, and evidence statements with fifth and sixth-grade students. Adams (1968) researched the teaching of propaganda techniques with 10th-grade students. At the end of the mentioned studies, the critical listening skills of students were found to have improved. These findings are significant in explaining that critical listening is a teachable skill. B Doğan (2017) prepared an education process on the subjects of determining the message that the text wants to convey, identifying propaganda, identifying the use of deceptive language, and identifying persuasive discourse. B Doğan (2017) implemented this process with seventh-grade students and found improvements in the students' critical listening skills. Similarly, Carkit (2018) applied an education process on analysis, questioning, comparison, and evaluation with seventh-grade students and reported improved critical listening skills among the students. In the aforementioned studies critical listening have been discussed from multiple perspectives and often focused on one or more aspects of this skill. This indicates that there is no study in the literature that covers all the skills under critical listening. Critical listening is not a structure that consists of one or more skills; it is a complex whole that covers various subjects and other skills. The positive results obtained from these practices may not necessarily indicate a full improvement in students' critical listening skills. Thus, we need research that deals with all aspects of critical listening. The findings from such studies can fill the gap in this field and yield information about the impact of a teaching process that is tailored for critical listening.

Purpose

Given the importance of being able to choose the necessary information from what is presented and to evaluate the accuracy of the information, critical listening skills are needed by all individuals. Nonetheless, research on critical listening has been concentrated within a certain period and the number of relevant studies remains very small. In the literature one or several dimensions of critical listening based on the teaching thereof are discussed. This indicates a gap in the field of teaching critical listening with all its aspects. Therefore, studies that deal with all dimensions of critical listening will contribute to the literature. The lack of recent research on critical listening skills, the focus on certain aspects of critical listening during teaching, and the significance of this skill for individuals constitute the purpose of our research. Hence, we aimed to investigate the impact of a practice tailored for critical listening on the critical listening skills of seventh-grade students. For this purpose, the answers to the following questions were sought:

• Is there a significant difference between the pre-test and post-test scores of an experimental group that receives training for improving critical listening skills?

• Is there a significant difference between the pre-test and post-test scores of a control group that does not receive training for improving critical listening skills?

• Is there a significant difference between the post-test scores of these experimental and control groups?

Method

Research Model

A quasi-experimental design was used in this research. Experimental research involves manipulating the independent variable and comparing measurements at least twice (Büyüköztürk, Kılıç-Çakmak, Akgün, Karadeniz & Demirel, 2014). We chose this design because it is the only way to determine the impact of a variable and when used appropriately, it is the most valid and reliable way to test cause and effect relations (Fraenkel & Wallen, 2006). We preferred an experimental design along with experimental and control groups to determine the impact of the relevant practice. The quasi-experimental design was used as one of the two groups was randomly assigned as the experimental group (Büyüköztürk et al., 2014).

Study Group

We carried out the research in the Mithatpaşa Secondary School in Sakarya after obtaining the necessary permissions. To form the experimental and control groups, we implemented a critical listening test for two seventh-grade classes.

Before comparing the critical listening test scores of students in each class, we first examined the normality of distribution. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test revealed that the data did not show normal distribution (p < 0.05). Therefore, we used the Mann-Whitney U test to compare the critical listening test scores of the two classes. The Mann-Whitney U test findings showed no significant difference between the classes in terms of critical listening test results (U = 611.00; p > 0.05). This indicates that the classes had equal levels of success in terms of critical listening skills before the practice. Then, one of the classes was randomly assigned as the experimental group and the other as the control group. There were 41 (18 girls, 23 boys) students in the experimental group and 40 (19 girls, 21 boys) in the control group.

Data Collection Tools

Developing an evaluation tool for critical listening skills

The text and the questions prepared for measuring critical listening skills are provided in the Appendix A and B. For determining the subject of the text, we consulted three Turkish teachers (Teacher A: female, 10 years of professional experience; Teacher B: male, 15 years of professional experience; Teacher C: female, 17 years of professional experience). The text was written by the researcher. The test consisted of open-ended questions about the skills that are covered under critical listening skills.

For the text we consulted the opinions of three Turkish teachers (Teacher A, Teacher B, Teacher C), two field experts (Expert A: female, a doctorate in Turkish language teaching; Expert B: male, a doctorate in Turkish language teaching), one evaluation and assessment expert (Expert C: female, a doctorate in evaluation and assessment), and two seventh grade students (one male, one female).

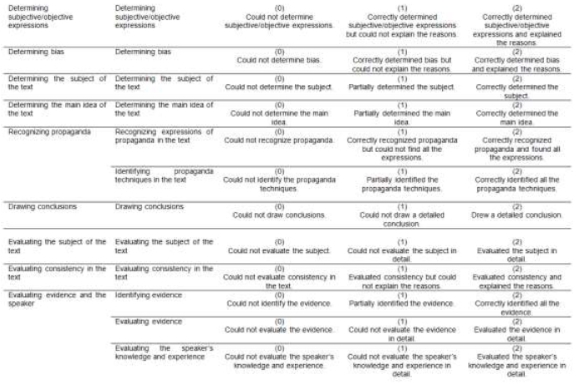

Preparing the rubric

After deciding on the score ranges, we prepared a rubric (Appendix D) for the evaluation of critical listening skills by consulting the opinions of the evaluation and assessment expert (Expert C:). For the pilot practice, two different raters (Rater A: researcher, female, a doctorate in Turkish language teaching; Rater B: researcher, male, professor in Turkish language teaching) scored the results and the correlation values for consistency between the raters were above 0.70 for all dimensions. Because the correlation coefficient was above 0.70, the rubric was considered to show high agreement between raters.

Data Collection

We used the critical listening test developed by me for data collection. After obtaining the necessary permissions for the research (approval from the ethics committee and the Ministry of National Education), we initiated the implementation process. I performed data collection and the practice in the experimental group. In the control group, the Turkish language teacher continued his lessons according to his own schedule. The teaching of critical listening was planned as 40 course hours and the whole practice, including the tests, was completed in 30 weeks.

Procedure

In this study I was also the teacher. The subject of the research requires of teachers to be informed about the practice. However, due to a lack of teachers to participate voluntarily, I carried out the practice. During the practice in the experimental group, I complied with all the predetermined stages and did not make any other implementations or changes that were not within the planned practice.

The education process basically consisted of providing information about the subject, giving the necessary explanations, and performing practices about the subject through listening to texts (listening to the text, doing activities and exercises about the text, and answering the questions). Students were allowed to take notes while listening. While selecting the listening texts, we took the students' level into account and ensured that the subjects were relevant. The texts were used with permission of the Science and Technology journal. The texts in the journal consisted of informative texts. Because these texts were to be used as listening materials, I audio-recorded the content of the texts. These recordings were used during the listening practice.

While planning the teaching process, we moved from easier to more difficult ones and grouped similar skills under certain categories. We began the practice with "determining the subject of the text," followed by "determining the main idea of the text", which is related to the former skill. Going from easier skills to more difficult ones, we focused on "determining subjective/objective expressions within the text" and "determining bias", which are included in the fifth and sixth-grade curricula. The latter is associated with "recognizing elements of propaganda", so we continued with this skill. In the next step, we began the teaching process of "evaluating the subject of the text and drawing conclusions." We then moved on to "evaluating consistency within the text" and "evaluating evidence and source."

The practices for critical listening skills were planned by consulting expert opinions. Before starting the teaching process, the texts and materials were examined by the Turkish language teacher of the experimental group (Teacher B) and a field expert (Expert A). The content of the training for critical listening skills is discussed below.

Determining the subject of the text. Before the listening practices, we determined the subject of the text by first discussing the concept of the subject and what the subject of the text referred to. We explained that the subject of the text should be expressed in one or a few words. We performed some exercises to determine the subjects of different texts. The students first listened to the texts and then they were asked to determine the subject. Finally, we discussed the text and revealed the subject.

Before the listening practice we determined the main idea of the text by first discussing the concept of the main idea and what the main idea of the text referred to. We explained that the main idea of the text should be expressed as a sentence and then began the practice. Students listened to different texts and they were asked to find the subject and the main idea of the text. We compared the two concepts to prevent confusion.

To recognise subjective/objective expressions in the text, we first discussed the concept of subjective/objective expressions and performed exercises to determine subjectivity/objectivity in some examples. Finally, we discussed the language of the texts while trying to determine subjective/objective expressions in the listening texts.

To recognise bias we first discussed the concept of biased text. We explained that a narrative can have either a biased or a neutral perspective. We explained to the students that this is associated with the presence of subjective expressions and expressions of emotion. We used the brainstorming technique in the classroom to reveal the emotional expressions in the text and listed the resulting emotional expressions. We also discussed the concept of tricky words and asked the students to create new tricky words. We gave the students a sample text and asked them to change the expression of the text. Then we moved on to the listening practices and the students were asked to determine whether the speaker's expression was biased or unbiased.

In recognising propaganda we first discussed the concept of propaganda and gave examples of advertisement expressions. We asked the students some questions about what the purpose of propaganda could be and why it would be used. We then explained that propaganda is related to the bias or neutrality of the narrative. We then explained propaganda techniques with examples according to Devine (1982:45-46) and Tompkins and Hoskisson (1995:107). These propaganda techniques included glittering generality, testimonial, transfer, name-calling, plain folks, card stacking, bandwagon, snob appeal, and rewards. After each narrative, we asked the students to give examples of these techniques from advertisements or create new examples. Finally, we created exercises to determine which propaganda techniques were used in the listening texts.

Evaluating the subject of the text we first reminded the students about the first stage of the subject. After determining the subject of the text, the students were asked to make personal evaluations. We developed exercises for listening skills. Then we asked the students to identify the subject of the listening text using worksheets and to evaluate the subject by explaining their own views.

In conclusion, we first reminded the students about the second stage of the main idea. We asked the students to complete the text with their own sentences, taking the subject and the main idea of the text into account. We developed exercises for listening skills. Then, we asked the students to identify the main idea of the listening text using worksheets and to draw a conclusion. We then expanded the scope of the listening practice and used worksheets to determine the subject of the text, evaluate the subject of the text, determine the main idea of the text, and draw conclusions. With this practice, we aimed to reinforce the previous topics and to prevent confusion between concepts.

Evaluating consistency within the text we first explained the concept of consistency. We discussed what properties a text should have to be consistent. We then discussed the subject of logical errors, gave examples, and asked the students to create new examples. We discussed whether texts containing logical errors could be consistent and how the flow of the text should be. We performed some activities for listening skills. Finally, we asked the students to listen to the texts and evaluate whether the text was consistent, and to detect any logical errors.

Evaluating evidence and the speaker, we first discussed the concepts of source, reference, and citation. After explaining these concepts, we held a class discussion on how to decide on the reliability of sources. Finally, we discussed the evaluation of the speaker' s expertise on the subject through listening exercises.

Data Analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 20 software was used to analyse the quantitative data. Because the data did not show normal distribution as a result of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (p < 0.05), the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the pre-test and post-test scores of the experimental and control groups regarding critical listening skills. Also, since the data were non-normally distributed (p < 0.05), the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare post-test scores between the experimental and control groups.

Findings

Critical Listening Pre-test and Post-test Scores of the Experimental Group

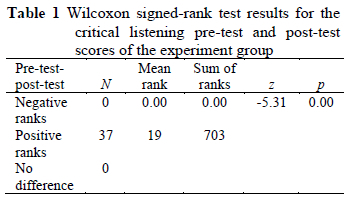

Table 1 shows the results of the comparison of pre-test and post-test scores among the experimental group that received training for critical listening.

We performed a Wilcoxon signed-rank test to determine any significant differences between the pre-test and post-test scores of the experimental group. As a result, we found a statistically significant difference between the students' critical listening pre-test and post-test scores (z = -5.31; p < 0.05). Given the mean rank and the rank-sum, we determined that the difference was in favour of the positive ranks, i.e., the post-test scores. The calculated effect size (d = 0.87) indicated this difference to be high. Therefore, the practiced curriculum had a significant effect on improving students' critical listening skills.

Critical Listening Pre-test and Post-test Scores of the Control Group

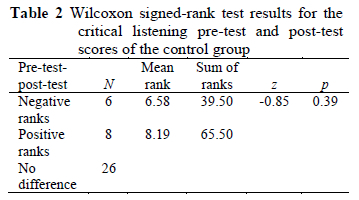

Table 2 gives the results of the comparison of pre-test and post-test scores among the control group that did not receive training for critical listening.

We performed the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to determine any significant differences between the pre-test and post-test scores of the control group. There was no statistically significant difference between the pre-test and post-test scores of these students (z = -0.85; p > 0.05).

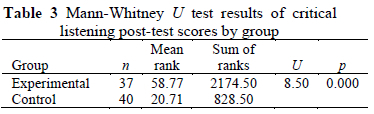

Critical Listening Post-test Scores of the Experimental and Control Groups Table 3 shows the results of post-test scores for the experimental and control groups.

We found a significant difference between the post-test scores of students who received critical listening training and those who did not (U = 8.50; p < 0.05). Given the mean rank, the experimental group had higher post-test scores than the control group. The effect size calculated with this test (d = 0.85) indicated this difference to be at a high level. Therefore, the education on critical listening had a significant impact on improving students' critical listening skills.

Discussion

With this study, we compared the pre-test and post-test scores of students in an experimental group who received training on critical listening skills and found a statistically significant difference in favour of their post-test scores. The effect size indicated a high level of difference. Hence, we concluded that critical listening education had a significant effect on improving students' critical listening skills. Devine (1961) and Laurent (1963) report improved critical listening skills of students who received such training. Numerous studies (Carkıt, 2018; Doğan, B 2017; Güneş, 2019; Laurent, 1963; Lockett, 1982; Lundsteen, 1963) report similar findings - even at different grades. Our findings seem to be consistent with the results obtained from previous research. Thus, we conclude that critical listening skills can be improved through appropriate education in different grades. Still, some studies had different findings. Groom (1970) found that 30 hours of critical listening training caused no improvement in students' critical listening skills. These dissimilar findings may have resulted from differences in the content of the education or differences in the sample groups.

In our study, we observed no statistically significant difference between the pre-test and post-test scores of the students in the control group who did not receive critical listening training. Previous research on critical listening (Brewster, 1956; Davis-Rice, 1982; Richards, 1976) investigated critical listening skills at different grades and found significant deficiencies in this regard, highlighting that students had problems in understanding what they listened to. Vandergrift (2004) argues that problems exist in the teaching of some areas that are related to listening because listening is the least explicit of the four language skills. Our findings support this conclusion.

After comparing the critical listening post-test scores of the experimental and control groups, we found a statistically significant difference in favour of the experimental group. The effect size again indicated a high level of difference. Previous research on critical listening education (Carkit, 2018; Doğan, B 2017; Güneş, 2019; Lockett, 1982; Lundsteen, 1963) also supports this finding. Although, some studies obtained different results (Groom, 1970). The dissimilarities in findings may have stemmed from differences in the content of the education or differences in the sample groups.

Conclusion and Recommendations

As a result of this research, it was determined that the experimental group who received critical listening education improved their critical listening skills. Since the research was conducted with seventh-grade students in a secondary school, the findings support that critical listening can be taught to students of 12 to 13 years old. Earlier studies with similar age groups also support this. These findings indicate that critical listening skills can be improved through practice. Hence, performing in-class practices for critical listening will contribute to the development of these skills. It is important to implement different texts during the teaching process. In the teaching process of the subjects within the scope of critical listening, first of all, students should be informed about the subject. It is important to follow a teaching order from easy to difficult. It may be beneficial to teach related subjects in a related way. Choosing the texts to be used in listening activities from current topics can be beneficial in terms of attracting students' attention. The education process should provide information about the subject, giving the necessary explanations, and doing exercises about the subject through listening to texts (listening to the text, doing activities and exercises about the text, and answering the questions). Students can take notes while listening.

Regarding the content of Turkish language teaching classes, there are insufficient explanations and exercises on critical listening, even though the subject is included in the Turkish curriculum. Furthermore, the students in the control group who did not receive critical listening education did not display improved critical listening skills. However, critical listening skills are included in the Turkish curriculum and Turkish textbooks, although not comprehensively. This reveals the necessity of new practices about critical listening and the need to enrich the curriculum and textbooks in this regard. Critical listening is not studied extensively in the Turkish language teaching literature. Hence, further research on critical listening will contribute to this field.

Authors' Contributions

NİA wrote the method, findings and discussion sections and AO wrote the introduction and background sections. Both authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Notes

i. This article is based on the doctoral thesis entitled, "Developing critical listening skills among middle school students."

References

Adams FJ 1968. Evaluation of a listening program designed to develop awareness of propaganda techniques. PhD dissertation. Boston, MA: Boston University. [ Links ]

Akyol H 2006. Yeni programa uygun Türkçe öğretim yöntemleri [Turkish teaching methods suitable for new program]. Ankara, Turkey: Kök Yayıncılık. [ Links ]

Azizoğlu Nİ 2022. Analysis of textbooks used in Turkish language courses in terms of critical listening skills. International Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 14(1):187-196. [ Links ]

Azizoğlu Nİ & Okur A 2021. Eleştirel dinleme becerisinin kapsamının incelenmesi [Examining the scope of critical listening skill]. RumeliDE Dil ve Edebiyat Arasttrmalan Dergisi, 22:327-337. https://doi.org/10.29000/rumelide.898553 [ Links ]

Beery A 1946. Listening activities in the elementary school. The Elementary English Review, 23(2):69-79. [ Links ]

Brewster LW 1956. An exploratory study of some aspects of critical listening among college freshmen. PhD dissertation. Iowa City, IA: State University of Iowa. Available at https://www.proquest.com/docview/302001861?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true. Accessed 8 November 2023. [ Links ]

Büyüköztürk Ş, Kılıç-Çakmak E, Akgün ÖE, Karadeniz Ş & Demirel F 2014. Bilimsel araştırma yöntemleri [Scientific research methods]. Ankara, Turkey: Pegem Akademi. [ Links ]

Carkıt C 2018. Ortaokul Türkçe derslerinde eleştirel dinleme/izleme uygulamaları üzerine bir eylem araştırması [An action research on critical listening/monitoring practices in secondary school Turkish lessons]. PhD dissertation. Kayseri, Turkey: Erciyes University. [ Links ]

Celepoğlu A 2012. Dinleme [Listening]. In L Beyreli (ed). Yazılı ve sözlü anlattm. Ankara, Turkey: Pegem A. [ Links ]

Crawford K 2009. Following you: Disciplines of listening in social media. Continuum, 23(4):525-535. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304310903003270 [ Links ]

Davis-Rice HJ 1982. Critical listening abilities of college students identified as superior, average, or poor readers. PhD dissertation. New York, NY: Hofstra University. Available at https://www.proquest.com/docview/303228197?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true. Accessed 8 November 2023. [ Links ]

Devine TG 1961. The development and evaluation of a series of recordings for teaching certain critical listening abilities. PhD dissertation. Boston, MA: Boston University. Available at https://open.bu.edu/ds2/stream/?#/documents/245657/page/3. Accessed 8 November 2023. [ Links ]

Devine TG 1982. Listening skills schoolwide: Activities and programs. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED219789.pdf. Accessed 23 November 2023. [ Links ]

Doğan B 2017. Strateji temelli dinleme etkinliklerinin yedinci stntf öğrencilerinin dinleme becerisiyle strateji kullanma düzeyine etkisi [The effect of strategy-based listening activities on the listening skills and strategy usage level of seventh grade students]. PhD dissertation. Malatya, Turkey: Inönü University. [ Links ]

Doğan Y 2007. İlköğretim ikinci kademede dil becerisi olarak dinlemeyi geliştirme çalışmaları [A study on improving listening as a language skill at secondary school]. PhD dissertation. Ankara, Turkey: Gazi University. [ Links ]

Early M 1954. Suggestions for teaching English. The Journal of Education, 3(137):7-20. [ Links ]

Fraenkel JR & Wallen NE 2006. How to design and evaluate research in education (6th ed). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Groom B 1970. An experimental study designed to develop selected informative listening skills of fifth and sixth grade students. PhD dissertation. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Available at https://www.proquest.com/docview/288334857?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true. Accessed 8 November 2023. [ Links ]

Grosser MM & Nel M 2013. The relationship between the critical thinking skills and the academic language proficiency of prospective teachers. South African Journal of Education, 33(2):Art. #639, 17 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v33n2a639 [ Links ]

Güneş G 2019. Eleştirel düşünme temelli dinleme/izleme eğitiminin eleştirel dinleme/izlemeye etkisi [The effect of critical thinking-based listening/monitoring training on critical listening monitoring]. MEd dissertation. Istanbul, Turkey: Yildiz Technical University. [ Links ]

Laurent MJ 1963. The construction and evaluation of a listening curriculum for grades 5 and 6. PhD dissertation. Boston, MA: Boston University. Available at https://www.proquest.com/docview/302138768?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true. Accessed 8 November 2023. [ Links ]

Lockett SR 1982. The development and assessment of instructional materials for the teaching of leadership skills to second grade students in selected public schools. PhD dissertation. Kalamazoo, MI: Western Michigan University. Available at https://www.proquest.com/docview/303264932?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true. Accessed 25 November 2023. [ Links ]

Lundsteen S 1963. Teaching abilities in critical listening in fifth and sixth grade pupils. PhD dissertation. Los Angeles, CA: California University. [ Links ]

Millî Eğitim Bakanliği 2019. Türkçe dersi öğretim programt (İlkokul ve Ortaokul 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 ve 8. Stntflar) [Turkish teaching program (Primary and Secondary School 1 st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th and 8th Grades)]. Ankara, Turkey: Author. Available at https://mufredat.meb.gov.tr/Dosyalar/20195716392253-02-T%C3%BCrk%C3%A7e%20%C3%96%C4%9Fretim%20Program%C4%B1%202019.pdf. Accessed 9 November 2023. [ Links ]

Moon J 2008. Critical thinking: An exploration of theory and practice. London, England: Routledge. [ Links ]

Richards RA 1976. The development and evaluation of a test of critical listening for use with college freshmen and sophomores. PhD dissertation. New York, NY: New York University. Available at https://www.proquest.com/docview/302760857?fromopenview=true&pq-origsite=gscholar. Accessed 8 November 2023. [ Links ]

Tompkins GE & Hoskisson K 1995. Language arts: Content and teaching strategies (3rd ed). Kent, OH: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Trace J 2013. Designing a task-based critical listening construct for listening assessment. Second Language Studies, 32(1):59-111. Available at https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/66c9cd24-b889-4209-ad95-b5fe7cea03b9/content. Accessed 8 November 2023. [ Links ]

Vandergrift L 2004. Listening to learn or learning to listen? Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 24:3-25. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190504000017 [ Links ]

Yalçın A 2006. Türkçe öğretim yöntemleri: Yeni yaklaştmlar [Turkish teaching methods: New approaches] (2nd ed). Ankara, Turkey: Akçağ Yayınları [ Links ].

Yore L, Bisanz GL & Hand BM 2003. Examining the literacy component of science literacy: 25 years of language arts and science research. International Journal of Science Education, 25(6):689-725. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690305018 [ Links ]

Received: 22 December 2020

Revised: 10 June 2023

Accepted: 18 July 2023

Published: 30 November 2023

Appendix A: Critical Listening Text

Appendix B: Critical Listening Test

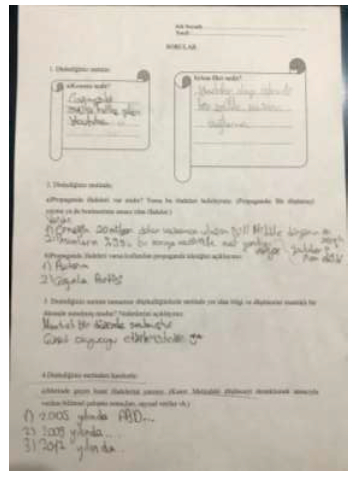

Appendix C: Critical Listening Test: Samples from Student Papers (Post-test of the Experimental Group)

Appendix D: Critical Listening Rubric